Advances in Clinical Medicine

Vol.

14

No.

04

(

2024

), Article ID:

84510

,

11

pages

10.12677/acm.2024.1441111

血清乳酸脱氢酶水平与住院患者 急性肾损伤的相关性研究及 预后风险评估

高雪1,徐翎钰2,管陈2,王雁飞2,张佳琪3,车琳2*

1青岛大学医学部,山东 青岛

2青岛大学附属医院肾病科,山东 青岛

3潍坊市益都中心医院肾内科,山东 潍坊

收稿日期:2024年3月17日;录用日期:2024年4月11日;发布日期:2024年4月16日

摘要

目的:探讨血清乳酸脱氢酶(LDH)水平与住院患者急性肾损伤(AKI)及死亡风险的相关性,为早期识别AKI提供指导。方法:纳入2023年1月至2023年12月在本院的4909例患者,对患者临床数据进行回顾性收集。根据血清LDH水平的四分位数将患者分为四组(Q1~Q4组),比较各组患者基线特征,使用logistic回归模型评估不同LDH组与住院患者AKI的相关性,探究LDH水平对AKI患者死亡的影响。进行亚组分析,以确定LDH水平与住院患者发生AKI风险在不同亚组间是否有差异。使用受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线评估LDH的预测效能。结果:4909例患者中有850例发生AKI,占总人群17.32%。AKI发生率随着LDH水平的增加而增加(12.96% vs. 13.45% vs. 18.09% vs. 22.78%)。在未校正的logistic回归分析中,与对照组Q1相比,Q3组(OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.19~1.85, P < 0.01)和Q4组(OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.79~2.74, P < 0.01)发生AKI的风险更高。使用模型1校正混杂因素后,Q3组和Q4组的调整OR (95% CI)分别为1.49 (1.20~1.87)和2.20 (1.78~2.72)。经模型2调整后观察到类似结果,Q3组、Q4组的OR分别为1.44、1.89,95% CI分别为1.19~1.85、1.51~2.38,Q3组P = 0.002,Q4组<0.001。在未调整的logistic回归分析中,与Q1组相比,Q4组(OR 5.07, 95% CI 1.97~13.09, P = 0.001)的AKI患者发生死亡的风险较高。使用模型1校正混杂因素后,Q4组的调整OR (95% CI)为5.30 (2.04~13.77)。经模型2校正后观察到类似结果,Q2组、Q4组的OR分别为3.90、2.97,95% CI分别为1.24~12.24、1.05~8.46。ROC曲线显示LDH对住院患者发生AKI具有预测价值,曲线下面积(AUC)为0.59 (95% CI 0.56~0.62, P < 0.05)。LDH预测AKI患者死亡的AUC为0.70 (95% CI 0.67~0.73, P < 0.05),当血清LDH水平与血清肌酐(Scr)结合起来预测住院患者AKI风险及AKI患者的住院死亡时,ROC曲线面积分别提高至0.60和0.80。结论:高水平血清LDH与住院期间发生AKI的风险独立相关,且LDH水平越高,AKI患者的死亡率越高。监测住院患者血清LDH水平可为早期识别AKI、改善患者预后提供指导。

关键词

急性肾损伤,乳酸脱氢酶,危险因素,死亡率

A Study on the Correlation between Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level and Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalised Patients and Prognostic Risk Assessment

Xue Gao1, Lingyu Xu2, Chen Guan2, Yanfei Wang2, Jiaqi Zhang3, Lin Che2*

1Medical College of Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

2Department of Nephrology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

3Department of Nephrology, Weifang Yidu Central Hospital, Weifang Shandong

Received: Mar. 17th, 2024; accepted: Apr. 11th, 2024; published: Apr. 16th, 2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: To explore the relationship between serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and acute kidney injury (AKI) in hospitalized patients to guide the early identification of AKI. Methods: This study included 4909 patients hospitalized in our hospital from January 2023 to December 2023, and patients’ clinical data were retrospectively collected. The study population was divided into four groups (groups Q1~Q4) according to the quartile of serum LDH levels. Differences in baseline characteristics between the 4 groups were compared. Using logistic regression models to evaluate the association of different serum LDH groups with AKI in hospitalized patients and investigating the effect of LDH levels on mortality in patients with AKI. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine differences in the association between LDH levels and the risk of developing AKI in hospitalized patients in different subgroups. ROC curve was used to assess the predictive performance of LDH. Results: AKI occurred in 850 of 4909 patients, representing 17.32% of the total population. AKI incidence increases with increasing LDH levels (12.96% vs. 13.45% vs. 18.09% vs. 22.78%). In unadjusted logistic regression analysis, the risk of AKI was higher in the Q3 (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.19~1.85, P < 0.01) and Q4 (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.79~2.74, P < 0.01) groups compared with the control group Q1. After adjustment for confounders using model 1, the adjusted OR (95% CI) was 1.49 (1.20~1.87) and 2.20 (1.78~2.72) for the Q3 and Q4 groups, respectively. Similar results were observed after adjustment using model 2, the ORs of the Q3 and Q4 groups were 1.44 and 1.89, respectively, with 95% CIs of 1.19~1.85 and 1.51~2.38, respectively, and P values of 0.002 and <0.001, respectively). In unadjusted logistic regression analysis, the risk of mortality in AKI patients was higher in the Q4 (OR 5.07, 95% CI 1.97~13.09, P = 0.001) compared with the control group Q1. After adjusting for the confounders using model 1, the adjusted OR (95% CI) was 5.30 (2.04~13.77) for the Q4 group. Similar results were observed after adjustment by model 2, the ORs of the Q2 and Q4 groups were 3.90 and 2.97, respectively, with 95% CIs of 1.24~12.24 and 1.05~8.46, P < 0.05. The ROC curve showed the predictive value of LDH for the development of AKI in hospitalized patients, with an area under the curve of 0.59 (95% CI 0.56~0.62, P < 0.05). The AUC for LDH in predicting death among patients with AKI was 0.70 (95% CI 0.67~0.73, P < 0.05). When serum LDH levels are combined with serum creatinine (Scr) to predict the risk of AKI in hospitalized patients and the in-hospital mortality of AKI patients, the ROC curve areas increase to 0.60 and 0.80, respectively. Conclusion: High serum LDH levels were independently associated with the risk of AKI during hospitalization, and higher LDH levels were associated with higher mortality in patients with AKI. Monitoring the serum LDH level in hospitalized patients can provide guidance for early detection of AKI.

Keywords:Acute Kidney Injury, Lactate Dehydrogenase, Risk Factors, Mortality

Copyright © 2024 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

急性肾损伤(Acute kidney injury, AKI)被定义为各种诱因引起的肾功能突然下降,导致肾小球滤过率下降、尿素和含氮废物潴留、水和电解质失衡,与住院时间延长、慢性肾脏病及死亡率增加相关 [1] [2] 。据统计,AKI在成人住院患者中的发生率约20%,重症监护病房的患者中发病率上升近60% [3] 。此外,肾功能持续丧失可能会增加患慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease, CKD)和终末期肾病的风险 [4] 。AKI会导致不同程度的不可逆肾单位损失、间质纤维化,并可能进展为CKD。目前AKI治疗的核心是针对AKI的病因进行治疗,并侧重于保护组织灌注、加强治疗监测,对症治疗及预防并发症。从治疗的角度来看,减少肾小管坏死和保护剩余肾单位的药物是降低AKI急性期死亡率和延缓慢性进展的最佳选择。然而,目前尚未开发出能够兼顾阻断肾小管细胞坏死而不引起因大量细胞的脱氧核糖核酸损伤而导致的恶性肿瘤 [5] 。由于AKI目前尚无特异性治疗方法,早期识别AKI患者,及时进行干预从而改善预后尤为重要。乳酸脱氢酶(Lactate dehydrogenase, LDH)是自然界最常见的酶之一,主要由两个亚基LDHA和LDHB组成的四聚体酶 [6] 。LDH在体内的作用是将乳酸和氧化型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸(Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NAD)分别转化为丙酮酸和还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸(Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide Hydride, NADH),广泛存在于机体各种组织中,以心肌、骨骼肌和肾脏中含量最为丰富 [7] 。细胞损伤坏死后,LDH被释放到血清中,导致LDH水平升高 [8] 。有研究表明,血清LDH在心肌梗死 [9] 、肺损伤 [10] 、脓毒血症 [11] 、恶性肿瘤 [12] 等患者中呈高水平。此外,LDH与疾病严重程度有关,较高的LDH水平与重症患者的较高死亡率有关,包括患有新冠肺炎病和其他疾病的患者 [13] [14] [15] 。有研究发现,LDH水平与AKI危重患者的死亡率独立相关 [16] 。然而,LDH水平与住院患者发生AKI的关系尚不清楚。因此,本研究旨在探究血清LDH水平对住院患者发生AKI的预测价值及对AKI患者死亡的影响。

2. 对象与方法

2.1. 研究对象

回顾性收集2023年1月至2023年12月于本单位住院的6040例患者的资料,根据纳入排除标准最终4909例患者纳入研究。排除标准:(1) 年龄 < 18岁;(2) 住院时间 < 48小时;(3) 合并尿毒症、进行肾脏替代治疗或行肾移植术;(4) 相关数据缺失。本研究经本单位医学伦理委员会批准。

2.2. AKI定义

AKI的诊断和分期标准采用2012年改善全球肾脏病预后组织(Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, KDIGO)指南,符合以下任何一项者可诊断为AKI。(1) 48小时内血清肌酐(Serum creatinine, Scr)值较基线上升超过26.5 μmol/L (0.3 mg/dL);(2) 7天内Scr较基线上升超过1.5倍。基线Scr值为住院期间第一次检测的Scr值。

2.3. 资料收集

收集包括年龄、性别、体重指数、手术史、吸烟史、饮酒史、住院天数、实验室检查指标、合并症、药物使用等人口学和临床资料。其中患者的合并症据国际疾病分类第十一次修订中的标准进行诊断。使用CKD-EPI公式计算估算肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate, eGFR)。

2.4. 统计学方法

采用SPSS 25.0、R软件进行统计分析,缺失值超过15%的变量被排除,缺失值及剔除的异常数据使用多重插补法进行插补。根据血清LDH水平的四分位数将研究对象分为四组(Q1~Q4组)。连续变量以 表示,组间比较采用方差分析或Kruskal-Wallis检验。分类变量以频数表示(百分比)表示,组间比较采用卡方检验或Fisher精确检验。为了验证LDH水平与住院患者发生AKI及AKI患者死亡的相关性,采用逐步回归分析为logistic回归模型筛选协变量,并采用4节点限制性立方样条图(Restricted cubic spline, RCS)模型,探讨LDH与AKI风险之间的非线性相关性。绘制受试者工作特征(Receiver operating characteristic, ROC)曲线,计算曲线下面积(Area under curve, AUC),以评估LDH的预测价值。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

3. 结果

3.1. 研究人群基线特征

最终4909例住院患者纳入研究,按照血清LDH水平将其分为四组进行基线特征比较(表1)。住院患者中850例发生AKI,AKI发生率为17.32%,死亡率2.55%。其中,四组患者发生AKI的人数分别为159例(12.96%)、165例(13.45%)、222例(18.09%)和304例(22.78%),AKI发生率随着LDH水平升高而增加(P < 0.01)。与LDH低水平组相比,血清LDH高水平组男性、手术史、吸烟者及饮酒者比例较低(均P < 0.01);血红细胞计数、血小板、白蛋白水平和eGFR较低(均P < 0.01);白细胞计数、转氨酶、总胆红素、尿酸较高(均P < 0.01);合并症与用药方面,高水平LDH组CKD、高血压比例较高(均P < 0.05),钙通道阻滞剂、抗生素使用比例较高(均P < 0.05),住院天数较长(P < 0.01),死亡率较高(P < 0.01)。

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients with different LDH levels

表1. 不同LDH水平患者的基线特征比较

eGFR:估算的肾小球滤过率;CKD:慢性肾脏病;ACEI/ARB:血管紧张素转化酶抑制剂/血管紧张素Ⅱ受体拮抗剂;AKI:急性肾损伤。

3.2. 血清LDH水平与AKI发生风险的相关性分析

为了探究LDH水平对住院患者发生AKI的影响,采用单因素、多因素logistic回归进行分析(表2)。在单因素logistic回归分析中,与对照组Q1相比,高水平LDH组(Q3组和Q4组)患者发生AKI的风险更高(均P < 0.01)。模型1经年龄、性别、体重指数校正后,与对照组相比,高水平LDH组与AKI风险显著相关(均P < 0.01)。模型2经年龄、性别、体重指数、红细胞计数、血红蛋白、凝血酶时间、白蛋白、谷草转氨酶、总胆红素、胆固醇、吸烟史、糖尿病、冠心病和高血压校正后,高水平LDH组患者发生AKI的风险分别增加1.44与1.89倍(均P < 0.05)。

Table 2. Relationship between serum LDH levels and development of AKI in hospitalized patients

表2. 住院患者血清LDH水平与发生AKI的关系

模型1:经年龄、性别、体重指数校正。模型2:经年龄、性别、体重指数、红细胞计数、血红蛋白、凝血酶时间、白蛋白、谷草转氨酶、总胆红素、胆固醇、吸烟史、糖尿病、冠心病和高血压校正。

3.3. 血清LDH水平与AKI患者死亡风险的相关性分析

采用单因素、多因素logistic回归分析AKI患者血清LDH水平与死亡风险的相关性(表3)。在单因素logistic回归分析中,在AKI患者中,与对照组相比,Q4组的AKI患者发生死亡的风险增高(P = 0.01)。模型1经年龄、性别、体重指数校正后,Q4组AKI患者死亡风险增加5.30倍(P < 0.01)。模型2经年龄、性别、体重指数、收缩压、白细胞计数、血红蛋白、胆固醇、谷草转氨酶、CKD、冠心病、ACEI/ARB、抗生素和非甾体类抗炎药校正后,Q2及Q4组AKI患者死亡风险分别增加3.90和2.97倍(均P < 0.05)。

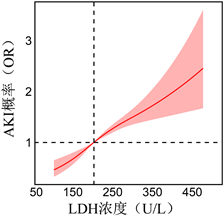

3.4. 血清LDH水平对AKI住院患者全因死亡的影响

本研究进一步探究了LDH水平与AKI风险及AKI患者死亡之间是否存在非线性相关性。基于logistic回归分析的RCS模型显示,LDH水平与AKI风险呈线性,AKI的风险随着LDH水平升高而增加,当LDH > 178 U/L时,对应的OR值 > 1 (图1)。

Table 3. Relationship between serum LDH levels and in-hospital mortality in patients with AKI

表3. AKI患者血清LDH水平与住院死亡的关系

模型1:经年龄、性别、体重指数校正。模型2:经年龄、性别、体重指数、收缩压、白细胞计数、血红蛋白、胆固醇、谷草转氨酶、CKD、冠心病、ACEI/ARB、抗生素和非甾体类抗炎药校正。

Figure 1. Correlation of serum LDH levels with AKI risk in hospitalized patients assessed using RCS

图1. 使用RCS评估血清LDH水平与住院患者AKI风险的相关性

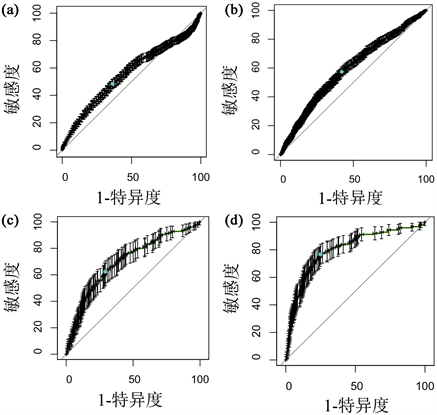

最后,使用ROC曲线分析来阐明LDH的预测效能。单一预测指标LDH对住院患者AKI风险预测的AUC为0.59 (95% CI 0.56~0.62, P < 0.05),而当血清LDH与Scr结合起来预测住院患者AKI风险时,结果显示AUC提高至0.60 (95% CI 0.57~0.63, P < 0.05) (图2(a)、图2(b))。此外,LDH预测AKI患者死亡风险的AUC为0.70 (95% CI 0.67~0.73, P < 0.05),当血清LDH水平与Scr结合起来预测AKI患者的住院死亡时,AUC提高至0.80 (95% CI 0.77~0.83, P < 0.05) (图2(c)、图2(d))。

Figure 2. ROC curves of LDH alone and in combination with Scr for prediction of AKI occurrence and death in AKI patients. (a) ROC curves for LDH prediction of AKI risk in hospitalized patients; (b) ROC curve of LDH combined with Scr for AKI risk prediction in hospitalized patients; (c) ROC curve of LDH for prediction of mortality risk in AKI patients; (d) ROC curve of LDH combined with Scr for prediction of mortality risk in AKI patients

图2. LDH单独及结合Scr预测AKI发生及AKI患者死亡的ROC曲线。(a) LDH对住院患者AKI风险预测的ROC曲线;(b) LDH联合Scr对住院患者AKI风险预测的ROC曲线;(c) LDH对AKI患者死亡风险预测的ROC曲线;(d) LDH联合Scr对AKI患者死亡风险预测的ROC曲线

4. 讨论

本研究首次探究了血清LDH水平与AKI发生风险及AKI患者住院全因死亡之间的关系。通过回顾性分析4909例患者的资料,比较不同血清LDH水平的住院患者的AKI发生率。结果显示,较高的LDH水平与住院患者的AKI发生风险及AKI患者死亡风险相关,LDH水平是影响住院患者AKI发生及AKI患者死亡的独立危险因素。

人体内的LDH是一种酶类蛋白质,在细胞内负责催化乳酸的氧化反应,将乳酸转化为丙酮酸,同时还可逆转地将丙酮酸还原为乳酸 [12] [17] [18] 。LDH广泛存在于机体的各种组织中,两个亚基LDHA和LDHB分别在骨骼肌和心肌中表达,其升高主要源于肺、肝脏和肌肉等组织的损伤 [12] 。LDH在缺氧细胞的糖酵解代谢中起重要作用。在缺氧条件下,细胞无法依赖氧气来进行常规的细胞呼吸,因此转向糖酵解途径以产生能量。糖酵解途径增强产生的大量丙酮酸需要在细胞质中转化为乳酸,而这离不开的LDH催化作用 [19] [20] [21] 。一些研究认为当细胞坏死或凋亡时LDH被释放到血清中可作为组织损伤的生物标志物 [22] [23] 。研究表明,LDH是许多疾病发生和进展的独立危险因素。Guan等发现高LDH水平与心脏手术相关AKI的风险增加独立相关,并在临床实践中用于预测高风险患者 [24] 。血清LDH是一种经济有效的预后指标,可用于横纹肌溶解性AKI患者的危险分层 [25] 。有大量研究显示,LDH水平升高COVID-19阳性住院患者发生AKI的独立危险因素,是细胞死亡和多器官衰竭的标志 [26] [27] [28] 。此外,LDH水平与急性胰腺炎、恶性肿瘤、COVID-19的严重程度及预后有关 [8] [29] [30] [31] 。与之前的研究一致,本研究显示随着LDH水平的增加,AKI发生率和2~3期比例也增加。

LDH水平升高与AKI相关的确切机制可由以下因素部分解释。第一,具有大量线粒体的肾小管细胞易因缺氧而发生损伤 [32] ,诱导肾脏内的代谢组学发生变化,包括糖酵解和脂肪酸代谢的激活及线粒体功能障碍 [33] 。第二,LDH是缺血性细胞损伤的重要反应因子,AKI发生后肾小管细胞中的LDH表达水平快速增加 [34] ,LDH从肾皮质释放到肾小囊腔和肾间质,最终到尿液和血液中 [35] 。第三,AKI发生时的炎症反应可导致肾小管细胞的损伤,而损伤的肾小管细胞释放如肿瘤坏死因子-α等炎症因子和单核细胞趋化蛋白-1等趋化因子进一步加重炎症反应 [36] 。这导致肾小管细胞膜通透性升高,增加LDH释放,使血清LDH水平升高 [35] [37] [38] 。

此外,本研究还发现经模型校正后,血清LDH水平是AKI患者住院死亡的重要预测因素。与Zhang等人发现血清LDH水平与AKI危重患者院内死亡率相关的研究结果一致 [16] 。本研究发现LDH水平与AKI风险呈线性相关,AKI的风险随着LDH水平升高而增加。因此应对LDH水平较高的患者进行更为积极的监测,并及时调整治疗策略。ROC曲线分析显示LDH水平预测住院患者AKI的效能优于Scr,为临床诊断AKI提供了参考价值。此外,当LDH和Scr联合预测AKI患者死亡风险时AUC增加至0.80,较单一指标表现出更好的预测效能。

这项研究具有一些局限性。第一,本研究为单中心回顾性研究,没有对患者出院后随访,没有分析肾功能的长期变化及长期死亡率,在未来的研究中可以对出院患者进行随访作进一步分析。第二,患者尿量数据因记录过程主观因素准确性较低而未被纳入研究,可能会影响AKI的检出率。

5. 结论

血清LDH水平升高与住院患者发生AKI的风险独立相关,且较高水平的血清LDH与AKI患者住院死亡率增加相关。血清LDH可早期识别住院患者AKI风险,临床医师在工作中应重视监测患者血清LDH水平。

文章引用

高 雪,徐翎钰,管 陈,王雁飞,张佳琪,车 琳. 血清乳酸脱氢酶水平与住院患者急性肾损伤的相关性研究及预后风险评估

A Study on the Correlation between Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level and Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalised Patients and Prognostic Risk Assessment[J]. 临床医学进展, 2024, 14(04): 952-962. https://doi.org/10.12677/acm.2024.1441111

参考文献

- 1. Turgut, F., Awad, A.S. and Abdel-Rahman, E.M. (2023) Acute Kidney Injury: Medical Causes and Pathogenesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12, Article 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010375

- 2. Vijayan, A., Abdel-Rahman, E.M., Liu, K.D., et al. (2021) Recovery after Critical Illness and Acute Kidney Injury. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN, 16, 1601-1609. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.19601220

- 3. Rossiter, A., La, A., Koyner, J.L., et al. (2024) New Biomarkers in Acute Kidney Injury. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 61, 23-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2023.2242481

- 4. Pickkers, P., Darmon, M., Hoste, E., et al. (2021) Acute Kidney Injury in the Critically Ill: An Updated Review on Pathophysiology and Management. Intensive Care Medicine, 47, 835-850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06454-7

- 5. Kellum, J.A., Romagnani, P., Ashuntantang, G., et al. (2021) Acute Kidney Injury. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7, Article No. 52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00284-z

- 6. Forkasiewicz, A., Dorociak, M., Stach, K., et al. (2020) The Usefulness of Lactate Dehydrogenase Measurements in Current Oncological Practice. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters, 25, Article No. 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-020-00228-7

- 7. Mishra, C., Ailani, V., Saxena, D., et al. (2022) Is There Any Correlation between Muscle Fatigue and Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels in Prediabetic Individuals? Exploration of Medicine, 3, 368-374. https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2022.00099

- 8. Huang, D.N., Zhong, H.J., Cai, Y.L., et al. (2022) Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Is a Sensitive Predictor of Systemic Complications of Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2022, Article ID: 1131235. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1131235

- 9. Węgiel, M., Wojtasik-Bakalarz, J., Malinowski, K., et al. (2022) Mid-Regional Pro-Adrenomedullin and Lactate Dehydrogenase as Predictors of Left Ventricular Remodeling in Patients with Myocardial Infarction Treated with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Polish Archives of Internal Medicine, 132, Article 16150. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16150

- 10. Poggiali, E., Zaino, D., Immovilli, P., et al. (2020) Lactate Dehydrogenase and C-Reactive Protein as Predictors of Respiratory Failure in COVID-19 Patients. Clinica Chimica Acta, 509, 135-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.012

- 11. Lu, J., Wei, Z., Jiang, H., et al. (2018) Lactate Dehydrogenase Is Associated with 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Sepsis: A Retrospective Observational Study. The Journal of Surgical Research, 228, 314-321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.03.035

- 12. Zhou, Y., Qi, M. and Yang, M. (2022) Current Status and Future Perspectives of Lactate Dehydrogenase Detection and Medical Implications: A Review. Biosensors, 12, Article 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12121145

- 13. Huang, Y., Guo, L., Chen, J., et al. (2021) Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level as a Prognostic Factor for COVID-19: A Retrospective Study Based on a Large Sample Size. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, Article 671667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.671667

- 14. Gotta, V., Tancev, G., Marsenic, O., et al. (2021) Identifying Key Predictors of Mortality in Young Patients on Chronic Haemodialysis-a Machine Learning Approach. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 36, 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa128

- 15. Su, D., Li, J., Ren, J., et al. (2021) The Relationship between Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level and Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. Biomarkers in Medicine, 15, 551-559. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2020-0671

- 16. Zhang D. and Shi, L. (2021) Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Level Is Associated with in-Hospital Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. International Urology and Nephrology, 53, 2341-2348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-021-02792-z

- 17. Khan, A.A., Allemailem, K.S., Alhumaydhi, F.A., et al. (2020) The Biochemical and Clinical Perspectives of Lactate Dehydrogenase: An Enzyme of Active Metabolism. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets, 20, 855-868. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530320666191230141110

- 18. Sharma, D., Singh, M. and Rani, R. (2022) Role of LDH in Tumor Glycolysis: Regulation of LDHA by Small Molecules for Cancer Therapeutics. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 87, 184-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.11.007

- 19. Deng, H., Gao, Y., Trappetti, V., et al. (2022) Targeting Lactate Dehydrogenase B-Dependent Mitochondrial Metabolism Affects Tumor Initiating Cells and Inhibits Tumorigenesis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Inducing mtDNA Damage. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 79, Article No. 445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-022-04453-5

- 20. Zhu, W., Ma, Y., Guo, W., et al. (2022) Serum Level of Lactate Dehydrogenase Is Associated with Cardiovascular Disease Risk as Determined by the Framingham Risk Score and Arterial Stiffness in a Health-Examined Population in China. International Journal of General Medicine, 15, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S337517

- 21. Zheng, J., Dai, Y., Lin, X., et al. (2021) Hypoxia‑Induced Lactate Dehydrogenase A Protects Cells from Apoptosis in Endometriosis. Molecular Medicine Reports, 24, Article No. 637. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2021.12276

- 22. Kato, G.J., Mcgowan, V., Machado, R.F., et al. (2006) Lactate Dehydrogenase as a Biomarker of Hemolysis-Associated Nitric Oxide Resistance, Priapism, Leg Ulceration, Pulmonary Hypertension, and Death in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood, 107, 2279-2285. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373

- 23. Pandarathodiyil, A.K., Ramanathan, A., Garg, R., et al. (2022) Lactate Dehydrogenase: The Beacon of Hope? Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences, 14, S1090-S1092. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_104_22

- 24. Guan, C., Li, C., Xu, L., et al. (2019) Risk Factors of Cardiac Surgery-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Development and Validation of a Perioperative Predictive Nomogram. Journal of Nephrology, 32, 937-945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-019-00624-z

- 25. Heidari Beigvand, H., Heidari, K., Hashemi, B., et al. (2021) The Value of Lactate Dehydrogenase in Predicting Rhabdomyolysis-Induced Acute Renal Failure; A Narrative Review. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine, 9, e24. https://doi.org/10.22037/aaem.v9i1.1096

- 26. Lu, J.Y., Hou, W. and Duong, T.Q. (2022) Longitudinal Prediction of Hospital-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19: A Two-Center Study. Infection, 50, 109-119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01646-1

- 27. Fisher, M., Neugarten, J., Bellin, E., et al. (2020) AKI in Hospitalized Patients with and without COVID-19: A Comparison Study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 31, 2145-2157. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020040509

- 28. Morell-Garcia, D., Ramos-Chavarino, D., Bauça, J.M., et al. (2021) Urine Biomarkers for the Prediction of Mortality in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients. Scientific Reports, 11, Article No. 11134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90610-y

- 29. Ma, Y., Shi, L., Lu, P., et al. (2021) Creation of a Novel Nomogram Based on the Direct Bilirubin-to-Indirect Bilirubin Ratio and Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels in Resectable Colorectal Cancer. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 8, Article 751506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.751506

- 30. Pei, Y.Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, Z.R., et al. (2022) Lactate Dehydrogenase as Promising Marker for Prognosis of Brain Metastasis. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 159, 359-368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04070-z

- 31. Lazar Neto, F., Salzstein, G.A., Cortez, A.L., et al. (2021) Comparative Assessment of Mortality Risk Factors between Admission and Follow-up Models among Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 105, 723-729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.013

- 32. Ma, Y., Potenza, D.M., Ajalbert, G., et al. (2023) Paracrine Effects of Renal Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells on Podocyte Injury under Hypoxic Conditions Are Mediated by Arginase-II and TGF-β1. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24, Article 3587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043587

- 33. Bonventre, J.V. and Yang, L. (2011) Cellular Pathophysiology of Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 121, 4210-4221. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI45161

- 34. Osis, G., Traylor, A.M., Black, L.M., et al. (2021) Expression of Lactate Dehydrogenase A and B Isoforms in the Mouse Kidney. American Journal of Physiology Renal Physiology, 320, F706-F718. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00628.2020

- 35. Zager, R.A., Johnson, A.C. and Becker, K. (2013) Renal Cortical Lactate Dehydrogenase: A Useful, Accurate, Quantitative Marker of in vivo Tubular Injury and Acute Renal Failure. PLOS ONE, 8, e66776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066776

- 36. Laskowski, J., Renner, B., Le Quintrec, M., et al. (2016) Distinct Roles for the Complement Regulators Factor H and Crry in Protection of the Kidney from Injury. Kidney International, 90, 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.02.036

- 37. Doi, K. and Rabb, H. (2016) Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Distant Organ Function: Recent Findings and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Kidney International, 89, 555-564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.019

- 38. Yan, H., Liang, X., Du, J., et al. (2021) Proteomic and Metabolomic Investigation of Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase Elevation in COVID-19 Patients. Proteomics, 21, e2100002. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.202100002

NOTES

*通讯作者。