Advances in Psychology

Vol.

11

No.

09

(

2021

), Article ID:

45060

,

7

pages

10.12677/AP.2021.119225

生活道德两难困境中的面孔刻板效应

王月华1*,王金华2,蔡瑶涵3,4

1郑州工商学院,河南 郑州

2新疆科技学院,新疆 库尔勒

3湖南师范大学,湖南 长沙

4华中科技大学,湖北 武汉

收稿日期:2021年8月7日;录用日期:2021年8月28日;发布日期:2021年9月7日

摘要

采用生活道德两难困境考察面孔吸引力对道德决策的影响。本实验将困境中的主人公的面孔特点操纵为高吸引力面孔和低吸引力面孔,被试任务为是否对主人公的求助行为帮助进行选择。结果发现,与低面孔吸引力的求助者相比,被试对面孔吸引力高的求助者做出更多的助人行为选择。实验结果说明了个体倾向于对面孔吸引力高的个体做出有利的道德决策。结合前人研究,推测在道德决策中也存在着“美丽溢价”效应。

关键词

面孔吸引力,道德决策,生活道德两难困境

The Stereotyped Effect of Faces in the Dilemma of Moral Dilemma in Life

Yuehua Wang1*, Jinhua Wang2, Yaohan Cai3,4

1Zhengzhou Technology and Business University, Zhengzhou Henan

2Xinjiang University of Science and Technology, Korla Xinjiang

3Hunan Normal University, Changsha Hunan

4Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan Hubei

Received: Aug. 7th, 2021; accepted: Aug. 28th, 2021; published: Sep. 7th, 2021

ABSTRACT

The moral dilemma of life is used to examine the influence of facial attractiveness on moral decision-making. In this experiment, the face characteristics of the protagonist in the dilemma were manipulated into high attractive faces and low attractive faces. The task of the subjects was to choose whether to help the protagonist’s help-seeking behavior. It was found that compared with the help-seekers with low facial attractiveness, the subjects made more choices of helping behaviors to the help-seekers with high facial attractiveness. The experimental results show that individuals tend to make favorable moral decisions for individuals with high facial attractiveness. Combined with previous studies, it is speculated that there is also a “beauty premium” effect in moral decision-making.

Keywords:Face Attractiveness, Moral Decision-Making, Life Moral Dilemma

Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

在人们的日常生活中存在着许多道德决策。道德决策(Moral decision making)是在涉及到规范和价值(如公平,正义)体系内的多种选择中,选出一种最符合社会规范的行为方案(Rilling & Sanfey, 2011)。那么人们是如何进行道德决策的呢?以皮亚杰和科尔伯格为代表的理性主义认为道德决策受到个体认知发展水平的影响,他们强调道德决策依赖推理和反思的过程。Haidt (2001)提出的社会直觉模型(social intuitionist model)认为道德决策是由快速的道德直觉引发的,然后才是道德推理,这种道德推理是一种较慢的过程,是对个体的道德决策做出的事后解释(Haidt, 2001)。为了调和这两种观点的矛盾,Greene (2007)提出了道德判断的双加工模型(dual-process model),即道德判断需要推理和直觉加工两者的共同参与(Greene, 2007; Greene, 2009; Greene, Morelli, Lowenberg, Nystrom, & Cohen, 2008; Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley, & Cohen, 2004),但二者是相互竞争的关系,当社会直觉加工占主导地位时则做出道义性判断,而推理加工占主导地位时则做出功利性判断(Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001)。

随后,一些研究者发现道德决策者的特点会影响道德决策。例如,Amit & Greene (2012)研究发现道德判断会受到决策者的认知风格的影响,并且视觉型认知风格的个体比言语型认知风格的个体倾向于做出道义性判断(Amit & Greene, 2012)。道德判断也会受到决策者的思维方式的影响,分析型思维方式的个体更倾向于做功利性的道德判断(Li, Xia, Wu, & Chen, 2018)。此外,决策者使用的语言也会影响道德决策,被试使用外语时更倾向于做出功利性决策(Cipolletti, Mcfarlane, & Weissglass, 2015; Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey, & Keysar, 2017)。

近年来的研究发现,道德两难情境中主人公的特点也会影响人们的道德决策。例如,Cikara,Farnsworth,Harris和Fiske (2010)采用人行桥道德困境任务考察了内外群体因素是否会调节人们的道德决策,研究结果表明当挽救内群体的人时,被试认为这种行为在道德上是可以接受的;而牺牲外群体的人时,被试认为在道德上是可以接受的,并且被试认为挽救外群体的人时在道德接受度上最低。Zhan等人(2018)的研究发现,当两难情境中的主人公是自己的朋友时(相比陌生人),个体更倾向于做出利他行为,做决策的速度更快,并且道德冲突较低。

以往的研究表明,面孔吸引力对人们的经济决策具有较大的影响(Chen et al., 2012; Jin, Fan, Dai, & Ma, 2017; Ma, Hu, Jiang, & Meng, 2015)。另外,相对于面孔吸引力低的个体,面孔吸引力高的个体会获得更多的雇佣和提拔的机会(Marlowe, Schneider, & Nelson, 1996),并且拥有更高的薪水(Andreoni & Petrie, 2008)。一项追踪调查研究显示,男性被试在大学时代的面孔吸引力与他们30岁和50岁时的年收入呈显著正相关(Scholz & Sicinski, 2015)。这些现象也被称为经济决策当中的“美丽溢价”效应,因此本研究拟进一步考察在道德决策中是否也存在这一效应。

因此,本研究拟采用生活道德两难困境任务考察面孔吸引力对道德决策的影响。在实验中,生活道德困境中求助者的面孔吸引力。以往的研究发现经济决策领域中存在明显的“美丽溢价”(beauty premium) 效应(Andreoni & Petrie, 2008; Chen et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2015; Marlowe et al., 1996; Scholz & Sicinski, 2015; Wang et al., 2017)。我们预测在道德决策领域也会出现“美丽溢价”效应,即在生活道德两难困境中,被试更愿意帮助高吸引力面孔的求助者。

2. 方法

2.1. 被试

招募34名(男15名)被试,视力或矫正视力正常。实验前被试签署知情同意书,实验后给予一定的报酬。被试平均年龄20.91岁(SD = 2.48)。

2.2. 实验材料

采用宋慧玲(2018)的研究中600张图片中选择高、低吸引力面孔各18张(男女各半)作为实验刺激材料,另外选择2张面孔图片作为练习试次的材料。

2.3. 道德困境任务

采用Zhan等人(2018)中的生活道德两难困境材料,本实验将困境材料中的求助者操纵为高吸引力和低吸引力面孔。每个道德困境材料由道德两难情境和相应的两个行为选择结果组成。道德两难情境指一个求助者急需你的帮助,但是同时你有一件重要的事情要做,你现在必须决定是否要放弃自己重要的事情来答应求助者的请求。道德困境材料中的两个行为选择包括:放弃自己重要的事情而帮助求助者的利他行为的描述;继续做自己重要的事情而忽视求助者请求的利己主义描述。被试的任务是从两个行为选项中做出选择。本实验包含12组生活道德困境,对困境中的求助者的面孔吸引力进行操纵,并形成24组生活道德困境文本材料。

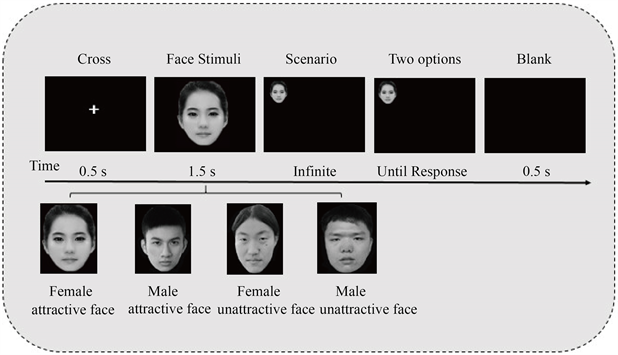

2.4. 实验程序

让被试舒服地坐在一个无噪音的房间内,实验前为被试介绍指导语以及实验流程,接着要求被试进行2个试次的练习实验,确保被试明白实验任务以及实验流程后,被试进入正式实验。实验流程如图1所示:首先在屏幕中央呈现一个白色的“+”,持续时间为500 ms,然后出现一张求助者面孔图片(高吸引力或低吸引力面孔),持续时间为1500 ms;随后呈现道德困境材料的文本形式,该文本以白色、宋体、20号字体呈现。被试读完并明白道德困境材料后,按“空格键”进入行为选择界面,行为选择文本格式与道德材料一致。被试在行为选择界面进行决策任务,若选择行为1就用左手食指按F键,选择行为2用右手食指按J键。然后是1000 ms的空屏,接下来继续下一个试次。正式实验包括2个block,每个block 18个trial,被试在block间进行3分钟的休息。反应按键在被试间进行平衡。

Figure 1. Experimental process

图1. 实验流程

2.5. 数据统计分析

采用SPSS Statistics22.0统计工具对被试的助人比率以及被试决策反应时进行配对样本t检验统计分析。被试的助人比率为被试做出助人行为选择的次数除以被试做出选择反应的总次数。

3. 结果

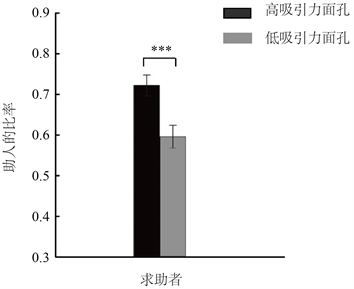

对被试的助人比率进行配对样本t检验,结果显示被试帮助高、低吸引力面孔求助者的概率差异显著[M高吸引力 = 0.72 (SD = 0.15), M低吸引力 = 0.6 (SD = 0.16); t(33) = 5.77, p < 0.001],说明与低面孔吸引力的求助者相比,被试对高面孔吸引力的求助者做出更多的帮助行为选择,即被试倾向于对高面孔吸引力的求助者做出更加积极的道德决策(如图2)。无论求助者是高吸引力面孔还是低吸引力面孔,被试选择助人的比率显著高于随机概率[t(36) = 6.04, p < 0.001],这说明被试具有利他主义倾向。

Figure 2. The bar chart of participants’ helping ratio under the condition of high and low attractiveness faces

图2. 被试在高低吸引力面孔条件下的助人比率柱状图

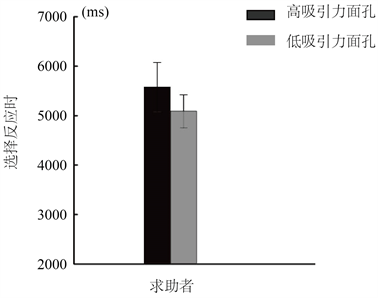

对被试的决策反应时进行配对样本t检验,结果显示被试的决策时间在两种面孔吸引力类型中的求助者间无显著差异[M高吸引力 = 5578.5 (SD = 0.15), M低吸引力 = 5087.6 (SD = 0.16); t(33) = 1.42, p = 0.17],但从被试决策的平均反应时可以看出,与低面孔吸引力的求助者相比,被试在高面孔吸引力的求助者条件下的决策时间会延长(如图3)。

Figure 3. The bar chart of participants’ choice response time under the condition of high and low attractiveness faces

图3. 被试在高低吸引力面孔条件下的选择反应时柱状图

4. 讨论

本实验采用生活道德两难困境探究面孔吸引力对道德决策的影响。研究结果表明,被试对面孔吸引力高的求助者倾向于做出更多的帮助行为选择,即被试倾向于对高吸引力面孔的个体做出更加有利的道德决策。

以往关于道德决策的研究多采用经典的电车困境或人行桥困境,有研究者认为这类困境与人们的生活实际具有一定的偏差,不能充分反应人们在现实情境中的行为反应。有研究发现,被试在假想的道德场景中的道德行为与个体真实的道德行为存在差异,而且增加被试对道德场景信息的可得性能够使被试的道德反应与真实情况下的反应一致(FeldmanHall et al., 2012)。生活道德两难困境涉及到个体自身利益与道德观念的冲突,道德困境的内容与生活情境更加贴近,因而这些困境所得出的实验结果能更好的反应被试的真实决策。本实验对生活道德困境中的求助者的面孔吸引力进行操纵,探究个体在道德决策中受面孔吸引力影响更有说服力。以往的研究表明,面孔吸引力在企业中的人事决策(Marlowe et al., 1996)、司法决策中(Christianson, 2010)、以及游戏中的金钱分配行为中(Ma & Hu, 2015)均存在“美丽溢价”效应。本实验的结果表明,面孔吸引力在生活道德两难困境中也存在“美丽溢价”效应。

此外,本实验结果显示被试在高、低面孔吸引力的求助者间的决策时间无显著差异,但与低吸引力面孔的求助者相比,被试在高吸引力面孔的求助者条件下的决策时间更长。Aharon等人(2001)研究表明,被试对面孔的吸引性进行评价时,对高吸引力面孔的注视时间会增加(Aharon et al., 2001)。另一项研究也表明,具有吸引力的面孔会增加个体对目标任务的判断的时间(Sui & Liu, 2009)。在本实验流程中,在决策界面具有求助者的面孔特点,而且在这个界面的决策时间并没有限制。结果中在高吸引力面孔的求助者条件下的决策时间更长,可能是被试不自觉地延长了对高吸引力面孔求助者的注视时间。

本实验中被试对不同面孔吸引力的个体做出的助人选择比率都高于随机水平,说明人们愿意做出牺牲自身利益而帮助别人的决策。有研究者利用不同的金钱分配和不同程度的电击任务探究个体的道德决策,实验过程中被试可以通过花钱减少电击疼痛,也可以增加电击疼痛来获利,研究结果表明,大多数人对他人的疼痛比自己的疼痛更加看重,证明了人们具有利他主义倾向(Crockett, Kurth-Nelson, Siegel, Dayan, & Dolan, 2014)。本实验的结果也表明了个体愿意做出牺牲自身利益而帮助别人的行为选择,同时也为研究者认为人们具有利他主义倾向提供了证据。

5. 结论

本研究采用生活道德两难困境证明了在道德领域也存在“美丽溢价”效应。在道德决策中,个体对高吸引力的面孔给予更多的关注,做出更多的助人行为。同时,本研究说明了个体具有利他主义倾向。

文章引用

王月华,王金华,蔡瑶涵. 生活道德两难困境中的面孔刻板效应

The Stereotyped Effect of Faces in the Dilemma of Moral Dilemma in Life[J]. 心理学进展, 2021, 11(09): 1996-2002. https://doi.org/10.12677/AP.2021.119225

参考文献

- 1. Greene, J. D., Morelli, S. A., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2008). Cognitive Load Selectively Interferes with Utilitarian Moral Judgment. Cognition, 107, 1144-1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004

- 2. Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The Neural Bases of Cognitive Conflict and Control in Moral Judgment. Neuron, 44, 389-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027

- 3. Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment. Science (New York, N.Y.), 293, 2105-2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872

- 4. Haidt, J. (2001). The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814-834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814

- 5. Hayakawa, S., Tannenbaum, D., Costa, A., Corey, J. D., & Keysar, B. (2017). Thinking More or Feeling Less? Explaining the Foreign-Language Effect on Moral Judgment. Psychological Science, 28, 1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617720944

- 6. Jin, J., Fan, B., Dai, S., & Ma, Q. (2017). Beauty Premium: Event-Related Potentials Evidence of How Physical Attractiveness Matters in Online Peer-to-Peer Lending. Neuroscience Letters, 640, 130-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.01.037

- 7. Li, Z., Xia, S., Wu, X., & Chen, Z. (2018). Analytical Thinking Style Leads to More Utilitarian Moral Judgments: An Exploration with a Process-Dissociation Approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 180-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.046

- 8. Ma, Q. G., Hu, Y., Jiang, S. S., & Meng, L. (2015). The Undermining Effect of Facial Attractiveness on Brain Responses to Fairness in the Ultimatum Game: An ERP Study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 9, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00077

- 9. Ma, Q., & Hu, Y. (2015). Beauty Matters: Social Preferences in a Three-Person Ultimatum Game. PLoS ONE, 10, e0125806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125806

- 10. Marlowe, C. M., Schneider, S. L., & Nelson, C. E. (1996). Gender and Attractiveness Biases in Hiring Decisions: Are More Experienced Managers Less Biased? Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.1.11

- 11. Rilling, J. K., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). The Neuroscience of Social Decision-Making. In S. T. Fiske, D. L. Schacter, & S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology (Vol. 62, pp. 23-48). Annual Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131647

- 12. Scholz, J. K., & Sicinski, K. (2015). Facial Attractiveness and Lifetime Earnings: Evidence from a Cohort Study. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 14-28. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00435

- 13. Sui, J., & Liu, C. H. (2009). Can Beauty Be Ignored? Effects of Facial Attractiveness on Covert Attention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 276. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.2.276

- 14. Wang, J., Xia, T., Xu, L., Ru, T., Mo, C., Wang, T. T., & Mo, L. (2017). What Is Beautiful Brings Out What Is Good in You: The Effect of Facial Attractiveness on Individuals’ Honesty. International Journal of Psychology, 52, 197-204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12218

- 15. Zhan, Y., Xiao, X., Li, J., Liu, L., Chen, J., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2018). Interpersonal Relationship Modulates the Behavioral and Neural Responses during Moral Decision-Making. Neuroscience Letters, 672, 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.02.039

- 16. 宋慧玲(2018). 面孔吸引力对道德决策的影响. 硕士学位论文, 长沙: 湖南师范大学.

- 17. Aharon, I., Etcoff, N., Ariely, D., Chabris, C. F., O’Connor, E., & Breiter, H. C. (2001). Beautiful Faces Have Variable Reward Value: fMRI and Behavioral Evidence. Neuron, 32, 537-551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00491-3

- 18. Amit, E., & Greene, J. D. (2012). You See, the Ends Don’t Justify the Means: Visual Imagery and Moral Judgment. Psychological Science, 23, 861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434965

- 19. Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2008). Beauty, Gender and Stereotypes: Evidence from Laboratory Experiments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 73-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.07.008

- 20. Chen, J., Zhong, J., Zhang, Y., Li, P., Zhang, A., Tan, Q., & Li, H. (2012). Electrophysiological Correlates of Processing Facial Attractiveness and Its Influence on Cooperative Behavior. Neuroscience Letters, 517, 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.082

- 21. Christianson, S. Å. (2010). Is Justice Really Blind? Effects of Crime Descriptions, Defendant Gender and Appearance, and Legal Practitioner Gender on Sentences and Defendant Evaluations in a Mock Trial. Psychiatry Psychology & Law, 17, 304-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710903566896

- 22. Cikara, M., Farnsworth, R. A., Harris, L. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2010). On the Wrong Side of the Trolley Track: Neural Correlates of Relative Social Valuation. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 5, 404-413. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq011

- 23. Cipolletti, H., Mcfarlane, S., & Weissglass, C. (2015). The Moral For-eign-Language Effect. Philosophical Psychology, 29, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2014.993063

- 24. Crockett, M. J., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Siegel, J. Z., Dayan, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2014). Harm to Others Outweighs Harm to Self in Moral Decision Making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 17320- 17325. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408988111

- 25. FeldmanHall, O., Mobbs, D., Evans, D., Hiscox, L., Navrady, L., & Dalgleish, T. (2012). What We Say and What We Do: The Relationship between Real and Hypothetical Moral Choices. Cognition, 123, 434-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.02.001

- 26. Greene, J. D. (2007). Why Are VMPFC Patients More Utilitarian? A Dual-Process Theory of Moral Judgment Explains. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 322-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.004

- 27. Greene, J. D. (2009). Dual-Process Morality and the Person-al/Impersonal Distinction: A Reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 581-584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.003

- 28. Greene, J. D., Morelli, S. A., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2008). Cognitive Load Selectively Interferes with Utilitarian Moral Judgment. Cognition, 107, 1144-1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004

- 29. Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The Neural Bases of Cognitive Conflict and Control in Moral Judgment. Neuron, 44, 389-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027

- 30. Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment. Science (New York, N.Y.), 293, 2105-2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872

- 31. Haidt, J. (2001). The Emotional Dog and Its Rational Tail: A Social Intuitionist Approach to Moral Judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814-834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814

- 32. Hayakawa, S., Tannenbaum, D., Costa, A., Corey, J. D., & Keysar, B. (2017). Thinking More or Feeling Less? Explaining the Foreign-Language Effect on Moral Judgment. Psychological Science, 28, 1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617720944

- 33. Jin, J., Fan, B., Dai, S., & Ma, Q. (2017). Beauty Premium: Event-Related Potentials Evidence of How Physical Attractiveness Matters in Online Peer-to-Peer Lending. Neuroscience Letters, 640, 130-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.01.037

- 34. Li, Z., Xia, S., Wu, X., & Chen, Z. (2018). Analytical Thinking Style Leads to More Utilitarian Moral Judgments: An Exploration with a Process-Dissociation Approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 180-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.046

- 35. Ma, Q. G., Hu, Y., Jiang, S. S., & Meng, L. (2015). The Undermining Effect of Facial Attractiveness on Brain Responses to Fairness in the Ultimatum Game: An ERP Study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 9, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00077

- 36. Ma, Q., & Hu, Y. (2015). Beauty Matters: Social Preferences in a Three-Person Ultimatum Game. PLoS ONE, 10, e0125806. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125806

- 37. Marlowe, C. M., Schneider, S. L., & Nelson, C. E. (1996). Gender and Attractiveness Biases in Hiring Decisions: Are More Experienced Managers Less Biased? Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.1.11

- 38. Rilling, J. K., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). The Neuroscience of Social Decision-Making. In S. T. Fiske, D. L. Schacter, & S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Annual Review of Psychology (Vol. 62, pp. 23-48). Annual Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131647

- 39. Scholz, J. K., & Sicinski, K. (2015). Facial Attractiveness and Lifetime Earnings: Evidence from a Cohort Study. Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 14-28. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00435

- 40. Sui, J., & Liu, C. H. (2009). Can Beauty Be Ignored? Effects of Facial Attractiveness on Covert Attention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 276. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.2.276

- 41. Wang, J., Xia, T., Xu, L., Ru, T., Mo, C., Wang, T. T., & Mo, L. (2017). What Is Beautiful Brings Out What Is Good in You: The Effect of Facial Attractiveness on Individuals’ Honesty. International Journal of Psychology, 52, 197-204. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12218

- 42. Zhan, Y., Xiao, X., Li, J., Liu, L., Chen, J., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2018). Interpersonal Relationship Modulates the Behavioral and Neural Responses during Moral Decision-Making. Neuroscience Letters, 672, 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2018.02.039

- 43. 宋慧玲(2018). 面孔吸引力对道德决策的影响. 硕士学位论文, 长沙: 湖南师范大学.

- 44. Aharon, I., Etcoff, N., Ariely, D., Chabris, C. F., O’Connor, E., & Breiter, H. C. (2001). Beautiful Faces Have Variable Reward Value: fMRI and Behavioral Evidence. Neuron, 32, 537-551. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00491-3

- 45. Amit, E., & Greene, J. D. (2012). You See, the Ends Don’t Justify the Means: Visual Imagery and Moral Judgment. Psychological Science, 23, 861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434965

- 46. Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2008). Beauty, Gender and Stereotypes: Evidence from Laboratory Experiments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 73-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.07.008

- 47. Chen, J., Zhong, J., Zhang, Y., Li, P., Zhang, A., Tan, Q., & Li, H. (2012). Electrophysiological Correlates of Processing Facial Attractiveness and Its Influence on Cooperative Behavior. Neuroscience Letters, 517, 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.082

- 48. Christianson, S. Å. (2010). Is Justice Really Blind? Effects of Crime Descriptions, Defendant Gender and Appearance, and Legal Practitioner Gender on Sentences and Defendant Evaluations in a Mock Trial. Psychiatry Psychology & Law, 17, 304-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710903566896

- 49. Cikara, M., Farnsworth, R. A., Harris, L. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2010). On the Wrong Side of the Trolley Track: Neural Correlates of Relative Social Valuation. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 5, 404-413. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsq011

- 50. Cipolletti, H., Mcfarlane, S., & Weissglass, C. (2015). The Moral For-eign-Language Effect. Philosophical Psychology, 29, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2014.993063

- 51. Crockett, M. J., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Siegel, J. Z., Dayan, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2014). Harm to Others Outweighs Harm to Self in Moral Decision Making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 17320- 17325. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408988111

- 52. FeldmanHall, O., Mobbs, D., Evans, D., Hiscox, L., Navrady, L., & Dalgleish, T. (2012). What We Say and What We Do: The Relationship between Real and Hypothetical Moral Choices. Cognition, 123, 434-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.02.001

- 53. Greene, J. D. (2007). Why Are VMPFC Patients More Utilitarian? A Dual-Process Theory of Moral Judgment Explains. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 322-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.004

- 54. Greene, J. D. (2009). Dual-Process Morality and the Person-al/Impersonal Distinction: A Reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 581-584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.003

NOTES

*通讯作者。