Botanical Research

Vol.05 No.06(2016), Article ID:19072,24

pages

10.12677/BR.2016.56024

Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Selection of Flower Color Variation

Ruijuan Zhang1,2, Yingqing Lu1*

1State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

Received: Nov. 8th, 2016; accepted: Nov. 27th, 2016; published: Nov. 30th, 2016

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

ABSTRACT

Flower color plays a key role in attracting pollinators, and a staggering variety of flower color variations including color parameters and pigmentation pattern exist in nature. Though many studies have been done on the molecular mechanisms of flower color variation, there is still much unknown, especially for pigmentation pattern. The contributions of pollinator and non-pollinator agents to natural selection on floral color variation are also unclear. The review discusses recent data on genetic mechanisms and natural selection of flower color variation. The summary may assist us to further analyze molecular mechanisms of flower color diversity and role of natural selection in flower color variation.

Keywords:Anthocyanin, Floral Color Variation, Pollinators, Fitness, Natural Selection

花色表型变异的分子机制及自然选择

张瑞娟1,2,鲁迎青1*

1中国科学院植物研究所系统与进化植物学国家重点实验室,北京

2中国科学院大学,北京

收稿日期:2016年11月8日;录用日期:2016年11月27日;发布日期:2016年11月30日

摘 要

花色对吸引传粉者具有非常重要的作用。自然界的花色具有多样性,主要包括色调和着色模式的变异。虽然前人对花色变异的物质和遗传基础做了大量的研究,但许多花色变异模式特别是着色模式的分子机制还不清楚。传粉者与非传粉者因素介导的自然选择对花色表型变异的选择机制也有许多未解之谜。本文主要对已知花色表型变异的分子机制及自然选择对花色表型的选择作用进行综述,以便进一步地探索花色多样性存在的机制和自然选择对花色进化方向的影响。

关键词 :花青素,花色变异,传粉者,适合度,自然选择

1. 引言

花部性状特别是花色在吸引传粉者方面起着非常重要的作用。花色的呈现具有一定的遗传基础,且需要环境的参与。植物生理生化环境和花青素代谢途径上结构或调控基因的突变均可能带来花色表型的变异。自然界花色表型具有多样性,主要体现在花色参数和着色模式上。但许多花色变异模式的存在机理还不清楚,花色变异与自然选择之间的关系也需要深入研究。本文就花色呈现的生理生化基础、已知的花色变异遗传机制和传粉者及非传粉介质(如基因多效性、环境因子、病原菌、啃食者等)对花色进化的影响进行总结,以利于探讨花色多样性存在的机制。

2. 花色呈现的分子基础

2.1. 花色呈现的生化生理基础

花色呈现物质主要有三大类:甜菜碱(betalains)、类胡萝卜素(carotenoids)和类黄酮(flavonoids) [1] [2] [3] 。其中甜菜碱、类胡萝卜素和部分类黄酮(如黄酮、黄酮醇、橙酮)可使花色呈现黄、红等色,类黄酮中的花青素是花色多样性最主要的物质基础。不同类型的花青素可使花呈现红、粉、紫、蓝等颜色。花青素在细胞质中不稳定而主要以花色苷(配糖体)的形式存在于植物液泡中 [1] [4] 。花青素苷元主要有天竺葵素(pelargnidin)、矢车菊素(cyanidin)、飞燕草素(delphinidin)、芍药花素(peonidin)、碧冬茄素(petunidin)和锦葵素(malvidin) 6大类 [5] [6] [7] 。它们均具有C6-C3-C6的基本骨架 [3] [8] [9] ,结构上的不同主要体现在B-环上羟基化、甲基化的程度。羟基越多,花色越蓝;甲基多则花色趋红。花青素苷元还会发生不同程度的糖基化和酰基化使其更稳定。糖基化使花色发生轻微红移;被香豆酸、肉桂酸等芳香族氨基酸酰化会使花色发生蓝移 [3] [10] 。羟基化、甲基化、糖基化和酰基化等修饰使花青素种类丰富多样,赋予了花色的多样性。随着技术的进步,越来越多的花青素被分离鉴定 [11] [12] [13] 。至2007年,自然界共有约500种花青素被鉴定 [14] 。除了花青素类别,花瓣细胞形状 [15] [16] [17] 、液泡pH [18] - [25] 、细胞共色素及金属离子的存在 [3] [12] 都会影响花色的呈现。如飞燕草素在较高的Fe3+下会使郁金香(Tulipa gesneriana)呈现蓝色 [26] [27] 。

2.2. 花色呈现的遗传基础

花青素的合成是研究比较清楚的一个次生代谢通路(图1) [3] [28] [29] 。它以香豆酰辅酶A(4-coumaroyl-CoA)

CHS:查尔酮合酶(chalcone synthase);CHI:查尔酮异构酶(chalcone isomerase);F3H:黄烷酮-3-羟化酶(flavanone 3-hydroxylase);F3’H:类黄酮-3’-羟化酶(flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase);F3’5’H:类黄酮-3’5’-羟化酶(flavonoid 3’5’-hydroxylase);DFR:二氢黄酮醇还原酶(dihydroflavonol reductase);ANS:花青素合酶(anthocyanidin synthase);UF3GT:尿苷二磷酸–葡萄糖–类黄酮-3-葡糖基转移酶(UDP glucose flavonoid-3-glucosyltransferase)

CHS:查尔酮合酶(chalcone synthase);CHI:查尔酮异构酶(chalcone isomerase);F3H:黄烷酮-3-羟化酶(flavanone 3-hydroxylase);F3’H:类黄酮-3’-羟化酶(flavonoid 3’-hydroxylase);F3’5’H:类黄酮-3’5’-羟化酶(flavonoid 3’5’-hydroxylase);DFR:二氢黄酮醇还原酶(dihydroflavonol reductase);ANS:花青素合酶(anthocyanidin synthase);UF3GT:尿苷二磷酸–葡萄糖–类黄酮-3-葡糖基转移酶(UDP glucose flavonoid-3-glucosyltransferase)

Figure 1.Anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (modified from [132])

图1. 花青素代谢途径(修改自[132])

和丙二酰辅酶A(malonyl-CoA)为底物,由结构基因(CHS、CHI、F3H、F3’H、F3’5’H、DFR和ANS)编码的一系列酶催化合成,并经糖基化、甲基化和酰基化等修饰后被转运至液泡中。其中F3H、F3’H和F3’5’H为花青素代谢途径的三个分支酶,其合成产物分别对应于天竺葵素、矢车菊素和飞燕草素。这些酶基因在许多植物中均已被克隆 [6] [28] 。它们可能是以多酶复合物的形式在内质网膜上行使催化功能 [2] [3] [30] 。花青素代谢与初级代谢之间具有密切的联系。来自圆叶牵牛的数据显示其底物香豆酰辅酶A与丙二酰辅酶A分别来自于苯丙氨酸(phenylalanine)合成途径和糖酵解(glycolysis)过程 [31] 。

已知花青素代谢途径由MYB、碱性螺旋–环–螺旋(bHLH)和WD40重复蛋白(WDR)三类调控因子主要以MBW三元复合物的形式调控 [3] [22] 。其中WDR的表达具有广泛性,而MYB和bHLH的表达却仅限于特定组织 [32] - [38] 。除参与花青素代谢途径外,不同组合的MBW复合物还参与液泡pH的控制、原花青素的合成、根毛形成、表皮细胞形状的决定和着色模式等过程。其中MYB决定了其功能的特异性 [33] [34] [39] 。在MBW复合物中,MYB和bHLH可分别特异地结合结构基因启动子区的cis元件——ANCNNCC (MRE, MYB-recognizing element)和CACN(A/C/T) (G/T) (BRE, bHLH-recognizing element),且MRE与BRE之间偏爱6 bp的间隔 [29] [40] [41] 。

但一些MYB可单独起作用。如在玉米(Zea mays)中,P1(subgroup7)可单独激活花青素合成的一部分基因(CHS, CHI, DFR, FLS)而促进玉米粒中鞣酐(phlobaphene)的合成 [25] [36] [42] [43] 。在拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)中,CHS、CHI、F3H、F3’H、FLS可被一些冗余的R2R3MYB (MYB11, MYB12, MYB111) (subgroup7)单独激活 [44] 。

3. 常见花色表型变异的遗传机制

花色表型多样性不仅体现在花色参数上,多样的着色模式(图2)更加丰富了花色的多态。这些变异可

a. 色折(color break):水仙(Narcissus pseudonarcissus) [61] 。b-f. 彩斑(variegation):b. 圆叶牵牛(Ipomoea purpurea) [62] ;c-e. 裂叶牵牛(I. nil) [63] ;f. 大丽花(Dahlia variabilis) [64] 。g-j. 缘环(marginal picotee):矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid) [65] 。k. 双色花(bicolor)大丽花(Dahlia variabilis) [66] 。l. 星状(star-type):矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid) [67] 。m-n. 紫外模式(UV/bull’s eye):黑心金光菊(Rudbeckia hirta):m. 可见光下;n. 紫外光下 [68] 。o-q. 脉色(venation):o. 金鱼草(Antirrhinum majus) [69] ;p. 矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid);q. 大花蕙兰(Cymbidium hybrida) [70] 。r-s. 芽红(bud flush):r. 苹果(Malus × domestica) [71] ;s. 岷江百合(Lilium regale) [71] 。t-v. 斑点(spot):t. 细长山字草(Clarkia gracilis) [72] ;u. 郁金香(Tulipa gesneriana cv. Murasakizuisho) [27] ;v. 蝴蝶兰(Phalaenopsis spp. I-Hsin Sun Beauty “KHM1065”) [73] 。w. 抬升的斑点(raised spot):东方百合(Oriental hybrid lily “Le Reve”) [74] 。x. 飞溅的斑点(splatter spot):亚洲百合(Asiatic hybrid lily “Latvia”) [74] 。y. 束状斑点(brushmarks):亚洲百合(Asiatic hybrid lily “Centrefold”) [74] 。z. 晕状斑点(spot-halo):毛地黄(Digitalis purpurea) [69]

a. 色折(color break):水仙(Narcissus pseudonarcissus) [61] 。b-f. 彩斑(variegation):b. 圆叶牵牛(Ipomoea purpurea) [62] ;c-e. 裂叶牵牛(I. nil) [63] ;f. 大丽花(Dahlia variabilis) [64] 。g-j. 缘环(marginal picotee):矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid) [65] 。k. 双色花(bicolor)大丽花(Dahlia variabilis) [66] 。l. 星状(star-type):矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid) [67] 。m-n. 紫外模式(UV/bull’s eye):黑心金光菊(Rudbeckia hirta):m. 可见光下;n. 紫外光下 [68] 。o-q. 脉色(venation):o. 金鱼草(Antirrhinum majus) [69] ;p. 矮牵牛(Petunia hybrid);q. 大花蕙兰(Cymbidium hybrida) [70] 。r-s. 芽红(bud flush):r. 苹果(Malus × domestica) [71] ;s. 岷江百合(Lilium regale) [71] 。t-v. 斑点(spot):t. 细长山字草(Clarkia gracilis) [72] ;u. 郁金香(Tulipa gesneriana cv. Murasakizuisho) [27] ;v. 蝴蝶兰(Phalaenopsis spp. I-Hsin Sun Beauty “KHM1065”) [73] 。w. 抬升的斑点(raised spot):东方百合(Oriental hybrid lily “Le Reve”) [74] 。x. 飞溅的斑点(splatter spot):亚洲百合(Asiatic hybrid lily “Latvia”) [74] 。y. 束状斑点(brushmarks):亚洲百合(Asiatic hybrid lily “Centrefold”) [74] 。z. 晕状斑点(spot-halo):毛地黄(Digitalis purpurea) [69]

Figure 2. Reported types of pigmentation pattern

图2.已报道的花色着色模式类型

能有利于增加植物的环境适应性。花色的变异具有一定的遗传基础,花青素代谢途径上结构或调控基因的突变(包括编码区和调控区)都或多或少会影响基因的功能或表达量而影响花色,基因的组织特异性表达或功能分化也会影响花色表型。

3.1. 花色的获得

花青素代谢为类黄酮的一个代谢分支,根据类黄酮类物质和代谢途径基因类似片段的存在与否,人们推断类黄酮代谢途径应该起源于植物登陆 [45] 。一些基因功能的获得可能源于基因重复后的功能分化,如CHI被推测起源于脂肪酸合酶基因功能分化 [46] 。从产物类别来看,在原始植物角苔类(liverworts)、苔藓(mosses)和石松类(club mosses)中发现有黄烷酮、黄酮和黄酮醇物质的出现 [47] 。在蕨类(ferns)植物里出现原花青素 [47] ,而花青素则从在松柏类裸子植物中出现到广泛存在于被子植物中 [48] [49] 。在调控基因方面,由于MYB较强的功能和组织特异性,花色素从无到有或从少到多的获得转换有可能通过cis或trans的方式使激活型MYB高表达 [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] 或抑制型MYB低表达 [55] 来实现(表1)。

3.2. 从蓝/紫色到红/粉色的花色变异

花色从蓝/紫色到红/粉色的变异通常是由于花青素从飞燕草素或矢车菊素到天竺葵素的转变,即花青素羟基数目的减少,因而常伴随羟基化酶基因F3’H或F3’5’H的功能失活或表达量降低(表2)。牵牛花仅含有矢车菊素和天竺葵素 [56] [57] [58] ,对于本身就具有蓝/紫色花的物种如圆叶牵牛(Ipomoea purpurea)、

Table 1. Summary of MYB mutations for gain of pigment

表1. 花色获得的基因突变形式

COD代表编码区的突变;CIS代表cis调控区的突变;Trans代表反式作用转录因子的改变;“?”代表原因不详。

Table 2. Summary of mutations causing flower color changes from blue/purple to red/pink

表2. 花色由蓝/紫色到红/粉色变化的基因突变形式

COD代表编码区的突变;CIS代表cis调控区的突变;Trans代表反式作用转录因子的改变;“?”代表原因不详。

裂叶牵牛(I. nil)、三色牵牛(I. tricolor)而言,其红/粉色变异通常是由于F3’H的编码区突变造成 [59] [60] 。对于同属内蓝/紫色到红/粉色的转变,若蓝/紫色由飞燕草素决定,通常会伴随F3’5’H的功能失活 [78] [80] - [85] [87] 或表达量下降 [53] ,有时也伴随F3’H在花组织中表达量的下降 [78] [80] [81] ;若蓝/紫色由矢车菊素决定,通常红/粉花中F3’H的启动子序列(cis调控)与蓝/紫花相比会发生变异而导致其表达量下调,且组织特异性表达调控使其仅降低花组织而不影响营养组织中矢车菊素的含量 [75] [76] [77] [87] [88] 。这是因为矢车菊素除了贡献于花色外,在紫外防御、抵御病原菌侵染或动物啃食、生长素极性运输等方面还具有重要的作用,所以F3’H的功能失活可能会影响整个植株的生长,组织特异性表达调控可以降低其有害多效性(deleterious pleiotropy)。统计数据表明植物营养组织中的花青素主要为矢车菊素,很少有植物会缺少有功能的F3’H拷贝,而F3’5’H会在许多科属如蔷薇科(Rosaceae)、菊科(Asteraceae)、拟南芥属(Arabidopsis)、番薯属(Ipomoea)、紫罗兰属(Matthiola)、郁金香属(Tulipa)植物中缺失 [45] [87] 。

由于F3’H或F3’5’H分支被阻断,花青素代谢通路只能走F3H-DFR的路径,所以花色从蓝/紫色到红/粉色的变异有时还伴随着DFR底物特异性的改变,即对底物DHK亲和性的提高,对DHQ和DHM亲和性的降低 [77] [78] [79] 。FLS表达量下降导致的黄酮醇含量下降也会使花由蓝紫色变为红色 [86] 。

3.3. 从蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色的花色变异

花色从蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色的变异通常被认为是花青素从有到无的变异,是质的变化。这些变化可能来自花青素代谢途径一个或多个步骤的阻断(表3)。代谢通路上结构基因的转座子插入 [62] [63] [89] [90] [91] 或移码突变 [92] 导致的功能失活或cis突变导致的表达量下降 [95] [96] 均会使植物产生白花。但结构基因的突变通常会使整个植物都无法产生花青素,最上游基因的突变可以让植物连黄酮、黄酮醇、黄烷酮等类黄酮物质也无法产生,会因而产生较多的有害多效性,降低植物适合度(e.g. [93] [94] )。R2R3-MYB [50] [51] [96] - [103] 、bHLH [104] [105] 和WDR [99] 的突变均可以造成花青素代谢途径上结构基因的表达下调而阻断花青素的合成,但由于R2R3-MYB具有较高的组织表达特异性和功能分化 [33] [34] [39] [50] [103] [106] [107] ,所以其突变具有较低的有害多效性。有观点认为自然选择应该偏爱R2R3-MYB的突变 [88] 。这与R2R3-MYB较bHLH和WDR及结构基因具有较高的异义和同义突变比率(ω)是一致的 [98] [108] [109] [110] [111] 。

花青素量的变化可能与花青素代谢途径基因的表达量变化有关,但具体机制还不清楚。在亚洲百合(Asiatic hybrid lilies Lilium spp.)中,MYB12的表达量与花瓣中花青素的积累量呈正比 [112] 。R2R3-MYB的表达量可解释小天蓝绣球(P. drummondii) (深红)与其近缘种P. cuspidate (浅蓝色)杂交F2代群体中花色的深浅 [53] [113] 。

3.4. 花着色模式的变异

花的着色式样主要有断色、彩斑、缘环、星状、紫外模式、斑点、脉色和芽红等(图2)。目前已知的花色着色模式成因主要有四种:病毒感染、转座子的插入及部分回复突变、siRNA介导的基因转录后沉默、基因特别是调控基因的时空特异性表达(表4)。黄水仙花(Narcissus pseudonarcissus)由于水仙花叶病毒的感染会产生断色现象 [61] 。通常转座子在基因内部的插入和部分回复突变会使花色呈彩斑状 [62] [63] [64] [89] [90] [102] 。双色花(包括缘环和星状)的形成通常是由于白色区域CHS的表达下调(主要由siRNA介导的其在转录后mRNA的降解造成) [65] [67] [114] [115] [116] ,或有色区域FLS的表达上调(原因未知) [65] 。UV模式、斑点、脉色和芽红等表型通常与花青素代谢途径的结构或调控基因的时空表达模式和不同拷贝数有关。在圆叶牵牛中,CHS-D主要在花檐中表达而控制整个花檐的着色,而CHS-E主要在花筒、花脉和花药中表达,可能与花筒的脉色和花脉上有色斑点的形成有关 [117] [118] [119] 。黑心金光菊(Rudbeckia hirta)在花瓣基部有F3H、F3’H、FLS、F6H、F7GT的高量表达使UV吸收类的黄酮醇类物质

Table 3. Summary of known mutations for flower color changes from blue/purple/red to white/yellow

表3. 花色由蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色变化的基因突变形式

COD代表编码区的突变;CIS代表cis调控区的突变;Trans代表反式作用转录因子的改变;“?”代表原因不详。

Table 4. Summary of known mutations that cause pigmentation patterns

表4. 已报道的花色着色模式相关变异

COD代表编码区的突变;CIS代表cis调控区的突变;Trans代表反式作用转录因子的改变;“?”代表原因不详。

高积累而形成类似蜜导的UV模式 [68] ;F3’H1-A在整个花瓣和DFR2-A/B在斑点的早表达及F3’5’H1-A/B和DFR1-A/B在花瓣中的晚表达可能是形成细长山字草(Clarkia gracilis)粉色带红色斑点表型的主要原因,但决定斑点位置的因子还有待确定 [72] [120] 。同样,花青素代谢途径结构基因在牡丹(Paeonia suffruticosa Cultivar “Jinrong”) [121] 和三色堇(Viola × wittrockiana Gams.) [122] 斑点位置出现高表达,这对它们花瓣上形成斑点具有很重要的作用。因为在斑点的形成过程中通常涉及多个结构基因的协同表达,且结构基因的表达受调控基因的影响,所以结构基因的时空特异性表达很大程度上可能是由调控基因的时空表达特异性决定的。许多研究表明R2R3-MYB的时空特异性表达对不同部位的着色具有非常重要的影响(表4) [50] [69] [71] [73] [74] [101] [103] [106] [107] [112] [123] [124] [125] [126] 。周围有光环的斑点表型(图2z)可能与斑点周围激活型因子(WDR)的移除或抑制型因子(R3-MYB)的流入有关 [68] 。R3-MYB和WD40均具有细胞间可移动性 [69] [106] 。在斑点处MBW复合物可促进R3-MYB的产生 [127] [128] ,斑点周围区域R3-MYB的流入与WDR的流出使其花青素合成较少或无,故呈光环型斑点的表型。另外,细胞形状 [15] [17] [69] 和Fe3+转运和存储蛋白的组织特异性表达 [26] [27] [129] 也可能影响花色斑点的形成。

目前MYB的时空特异性表达机制并不清楚。影响营养组织和芽红着色的R2R3-MYB通常会受光的诱导而高表达,且抑制型的R3-MYB会被激活参与该过程以避免过激反应 [106] [127] ,但环境特别是光诱导花青素合成的分子机制并不清楚。R2R3-MYB启动子区甲基化程度的不同会决定其表达与否而影响花青素合成部位,但DNA甲基化的组织特异性机制也未知 [125] 。

4. 花色表型变异的自然选择机制

花色的变异可能会带来传粉者或其访问频率的变异,传粉者与花色的相互关系对花色进化具有重要的意义。长期以来,人们对传粉者在花色亿万年的选择中发挥的作用十分好奇。此外,非传粉者因素(自然环境、病原菌、啃食者、基因多效性等)也会影响花色多态性 [132] [180] [181] 。

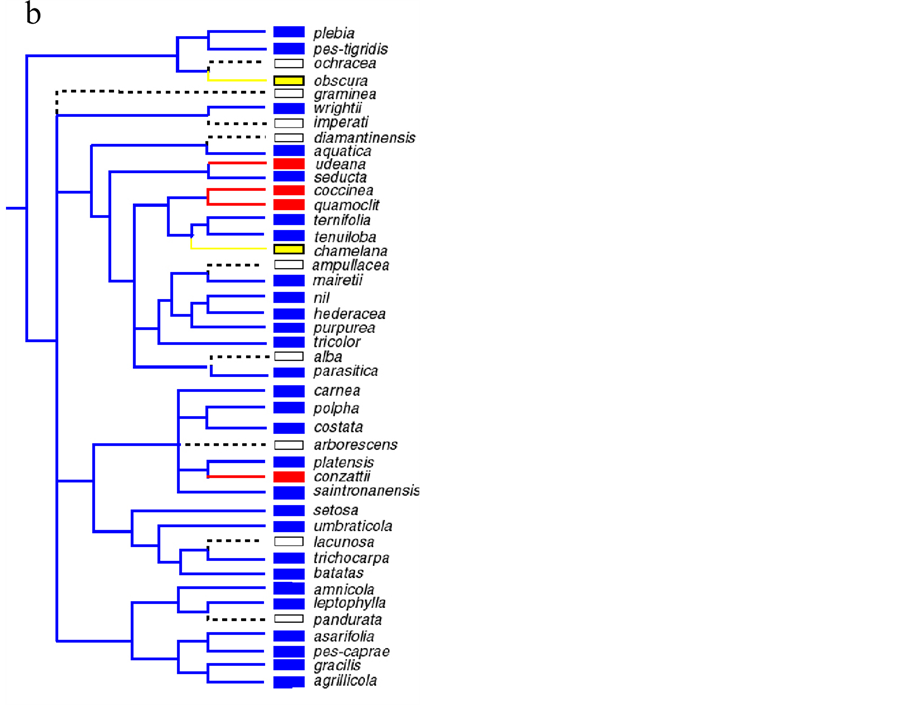

4.1. 花色转换方向与传粉者偏好

在陆地植物中发生过多次独立的花色从蓝/紫色到红/粉色或花色从蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色的转换,如曼陀罗属(Iochroma)、番薯属(Ipomoea)、钓钟柳属(Penstemon)、耧斗菜属(Aquilegia) (图3a-d)、闭鞘姜属(Costus) [45] [75] - [81] [87] [92] [130] [131] [132] 。在这些属中蓝紫色常为原始色,花色从蓝/紫色到红/粉色和蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色的转换比较常见,而反向转换则较少 [92] [132] [133] 。已记录的反向转换包括在苦苣苔科(Gesneriaceae)的三个属(Sinningia,Paliavana和Vanhouttea)中曾发生过多次花色从红色到蓝色的转换 [134] ,在黄蕊花属(Dalechampia)和枫属(Acer)中曾分别发生过三次花色从绿色或黄色到红色或紫色的转换 [135] ,在沟酸浆属(Mimulus)中也发生过花色从黄色到红色或粉色的转换(图3e) [52] 。花色转换方向的不对称性对花色的进化方向具有很大的限制 [132] 。目前对于花色着色模式的进化转换研究较少。仅有研究认为金鱼草的脉色可能为祖先性状,在全红的花瓣背景下脉色的作用被红色掩盖进而导致脉色消失 [50] [124] 。

通常,花色从蓝/紫色到红/粉色的转换伴随传粉者从蜂类(bees)到蜂鸟(hummingbirds)的转换,从蓝/紫/红色到白/黄色的转换伴随传粉者从蜂类或蜂鸟到蛾类(moths)的转换 [45] [87] [132] [136] 。花色的质变导致的传粉者类型的改变在许多科属如番薯属 [75] 、沟酸浆属 [137] [138] [139] 、耧斗菜属 [100] 、碧冬茄属(Petunia) [140] 、假番薯属(Ipomopsis) [141] [142] 中均观察到。通常为了避免对同种传粉者的竞争,同域分布的两近缘种(异域分布时通常具有相同花色)会分化出不同的花色 [53] [113] [143] [159] [160] [161] [162] 。传粉者对花色的量变是否具有区分能力还存在许多不确定性 [144] [145] [146] 。着色模式的变化通常会影响传粉者的访问频率,具有较明显斑点或花蜜指示标志的花色类型 [147] - [152] 会受到偏爱。

4.2. 传粉者介导的自然选择对花色进化的影响

传粉者对花色表型变异的区别访问是否对花色的进化产生选择性作用,通常要看该区别访问是否造成不同花色类型植物适合度(fitness)的不同 [132] 。植物适合度组分(fitness components)包括结果率、结籽率、萌发率、存活率、可育率等生活史性状。适合度反映一个个体能够产生的有活力的后代数量。

多数研究缺乏对不同花色变异的适合度的评估(e.g. [75] [100] [124] [137] [138] [140] )。一些研究只测量了部分适合度成分但未检测到传粉者对花色的选择作用(e.g. [113] [143] [154] [156] )。还有的研究注意到不同花色类型间适合度成分有差异且传粉者有偏爱,但无确切的实验和分析证据表明该差异是由传粉者造成(e.g. [72] [139] [152] [164] [166] [169] [175] [191] )。但相当数量的研究观测到传粉者的区别访问会带来不同花色类型植物适合度组分的不同(表5)。不同传粉者对不同花色类型的偏爱可能会使得同一属不同物种或同种物种不同个体间基因流减少,导致花色的歧化选择(disruptive selection) [141] [142] [157] [158] 。在同域地区为了避免对同种传粉者的竞争,花色也会发生歧化 [159] 。同种传粉者对不同花色类型访问次数及取食时间的差异导致的花粉输出与沉积量的差异对花色多样性的维持具有重要作用 [153] [167] 。传粉者对花色某一类型的偏爱性可导致花色的方向性选择(directional selection) [145] [146] [151] [165] [168] [170] [172] 或稳定性选择(stabilizing selection) [163] 。有时,某一花色类型在受到传粉者低访问时自交率的增加会维持其基因频率在一定水平,对花色产生平衡选择(balancing selection) [168] [169] [170] [177] [178] [179] ,从而维持花色多态性。

Table 5. Effects of flower color on pollinator visits and fitness components

表5. 花色对传粉者和适合度组成分的影响

“比较的花色或着色模式”中粗体部分表示该花色类型适合度较高;“适合度成分”中粗体部分表示有显著差异的适合度成分;“-”表示无实验证据。

a. 曼陀罗属(Iochroma) [78] ;b. 番薯属(Ipomoea) [45] ;c. 钓钟柳属(Penstemon) [132] ;d. 耧斗菜属(Aquilegia) [131] ;e. 沟酸浆属(Mimulus) [52] ;d中的星号表示推断的传粉综合征之间的转换。

a. 曼陀罗属(Iochroma) [78] ;b. 番薯属(Ipomoea) [45] ;c. 钓钟柳属(Penstemon) [132] ;d. 耧斗菜属(Aquilegia) [131] ;e. 沟酸浆属(Mimulus) [52] ;d中的星号表示推断的传粉综合征之间的转换。

Figure 3. Some generic phylogenies showing flower color transitions

图3. 一些属植物花色转换系统树

在进化过程中,植物为适应不同的传粉者会使花部特征特异化。如被蜂鸟传粉的花通常为红色、具有较长的花筒、较窄的花檐、外突的雄蕊和柱头、分泌大量但糖浓度较低的花蜜,被蜂类传粉的花大多为蓝紫色、具较宽的花筒和花檐、内嵌的雄蕊和柱头、分泌少量但高浓度的花蜜,而被蛾类传粉的花则多为白色、花筒较长、有芳香气味且经常在夜间开放,具低浓度高量花蜜 [132] [136] [182] [183] 。花色与其他花性状之间具有高度的相关性(e.g. [184] [185] [186] ),对其他花性状的选择也可能会影响花色的变异。性状之间的相互关联和权衡是限制花色方向性进化的一个因素 [187] 。

4.3. 非传粉者因素介导的自然选择对花色进化的影响

非传粉者因素对不同花色类型的适合度也具有一定的影响(表5)。因为不同的花色类型对光照、降水量、温度、海拔、经纬度等环境的适应能力可能不同,所以环境的异质性可导致不同花色类型在不同地区分布的差异 [152] [157] [158] [159] [168] [170] [171] [190] ,可能会介导花色的歧化或动态选择(fluctuating selection)。啃食者与传粉者偏爱的相同可能带来与传粉者作用相反的拮抗选择(antagonistic selection) [152] [165] 。环境因子、啃食者或病原菌在花色的多态性维持方面起着非常重要的作用,其通常还会限制花色的方向性进化 [165] [168] [170] [171] [172] 。

基因的多效性也会影响花色。有时,杂合体花色表型会表现出超显性(overdominance) [165] [173] [174] [175] [176] 而维持等位基因频率的平衡,对花色产生平衡选择。由于突变基因的有害多效性,一些白花个体与有色花相比,通常具有较低的萌发率、存活率、可育率或抵御啃食者和病原菌的能力较差,因而具有较低的适合度而受到纯化选择(purifying selection),结果在群体中占有较低的频率 [93] [94] [165] [188] [189] 。

5. 展望

花色表型的丰富变异既存在于种间,也存在于种内。花色表型变异的分子机制和自然选择的研究对探究生物多样性的存在机制具有重要意义。目前对种内的数量变异研究相对较少。传粉者或非传粉者因素对花色变异所起的选择作用有可能影响花色的进化,但其作用机制还需要更多研究。已有的研究结果多数还需要生态学的调查加以确认。花色表型变异导致的植物-传粉者关系的变化如何影响物种的分化,进而影响生态系统的动态变化尚需更多关注。特别是随着气候变化的加剧,自然环境对植物性状和传粉者访花行为的影响将越来越受重视。显然,相关研究将会深化我们对未来气候下动植物互作关系的认识。

基金项目

国家自然科学基金:91331116。

文章引用

张瑞娟,鲁迎青. 花色表型变异的分子机制及自然选择

Molecular Mechanisms and Natural Selection of Flower Color Variation[J]. 植物学研究, 2016, 05(06): 186-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/BR.2016.56024

参考文献 (References)

- 1. Cooper-Driver, G.A. (2001) Contributions of Jeffrey Harborne and Co-Workers to the Study of Anthocyanins. Phytochemistry, 56, 229-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00455-6

- 2. Grotewold, E. (2006) The Genetics and Biochemistry of Floral Pigments. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 57, 761-780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105248

- 3. Tanaka, Y., Sasaki, N. and Ohmiya, A. (2008) Biosynthesis of Plant Pigments: Anthocyanins, Betalains and Carotenoids. The Plant Journal, 54, 733-749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03447.x

- 4. Marrs, K.A., Alfenito, M.R., Lloyd, A.M. and Walbot, V. (1995) A Glutathione S-Transferase Involved in Vacuolar Transfer Encoded by the Maize Gene Bronze-2. Nature, 375, 397-400. https://doi.org/10.1038/375397a0

- 5. Kong, J.M., Chia, L.S., Goh, N.K., Chia, T.F. and Brouillard, R. (2003) Analysis and Biological Activities of Anthocyanins. Phytochemistry, 64, 923-933. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00438-2

- 6. Chopra, S., Hoshino, A., Boddu, J. and Iida, S. (2006) Flavonoid Pigments as Tools in Molecular Genetics. In: Grotewold, E., Ed., The Science of Flavonoids, Springer, New York, 147-173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-28822-2_6

- 7. 黄金霞, 王亮生, 李晓梅, 鲁迎青. 花色变异的分子基础与进化模式研究进展[J]. 植物学通报, 2006, 23(4): 321- 333.

- 8. Stobiecki, M. and Kachlicki, P. (2006) Isolation and Identification of Flavonoids. In: Grotewold, E., Ed., The Science of Flavonoids, Springer, New York, 47-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-28822-2_2

- 9. Sisa, M., Bonnet, S.L., Ferreira, D. and Van der Westhuizen, J.H. (2010) Photochemistry of Flavonoids. Molecules, 15, 5196-5245. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15085196

- 10. Tanaka, Y., Tsuda, S. and Kusumi, T. (1998) Metabolic Engineering to Modify Flower Color. Plant and Cell Physiology, 39, 1119-1126. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029312

- 11. Harborne, J.B. and Baxter, H. (1999) The Handbook of Natural Fla-vonoids. Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0039-9140(00)00629-9

- 12. Harborne, J.B. and Williams, C.A. (2000) Advances in Flavonoid Research Since 1992. Phytochemistry, 55, 481-504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00235-1

- 13. Harborne, J.B. and Williams, C.A. (2001) Anthocyanins and Other Fla-vonoids. Natural Product Reports, 18, 310-333. https://doi.org/10.1039/b006257j

- 14. Guo, J., Han, W. and Wang, M.H. (2008) Ultraviolet and Environmental Stresses Involved in the Induction and Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis: A Review. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7, 4966-4972. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajb08.090

- 15. Noda, K., Glover, B.J., Linstead, P. and Martin, C. (1994) Flower Color Intensity De-pends on Specialized Cell-Shape Controlled by a Myb-Related Transcription Factor. Nature, 369, 661-664. https://doi.org/10.1038/369661a0

- 16. Perezrodriguez, M., Jaffe, F.W., Butelli, E., Glover, B.J. and Martin, C. (2005) Devel-opment of Three Different Cell Types Is Associated with the Activity of a Specific MYB Transcription Factor in the Ventral Petal of Antirrhinum majus Flowers. Development, 132, 359-370. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.01584

- 17. Baumann, K., Perez-Rodriguez, M., Bradley, D., Venail, J., Bailey, P., Jin, H., Koes, R., Roberts, K. and Martin, C. (2007) Control of Cell and Petal Morphogenesis by R2R3 MYB Transcription Factors. Development, 134, 1691-1701. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.02836

- 18. Yoshida, K., Kondo, T., Okazaki, Y. and Katou, K. (1995) Cause of Blue Petal Color. Nature, 373, 291. https://doi.org/10.1038/373291a0

- 19. Van Houwelingen, A., Souer, E., Spelt, K., Kloos, D., Mol, J. and Koes, R. (1998) Analysis of Flower Pigmentation Mutants Generated by Random Transposon Mutagenesis in Petunia hybrida. The Plant Journal, 13, 39-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00005.x

- 20. Fukada-Tanaka, S., Inagaki, Y., Yamaguchi, T., Saito, N. and Iida, S. (2000) Colour-Enhancing Protein in Blue Petals. Nature, 407, 581. https://doi.org/10.1038/35036683

- 21. Yamaguchi, T., Fu-kada-Tanaka, S., Inagaki, Y., Saito, N., Yonekura-Sakakibara, K., Tanaka, Y., Kusumi, T. and Iida, S. (2001) Genes Encoding the Vacuolar Na+/H+ Exchanger and Flower Coloration. Plant and Cell Physiology, 42, 451- 461. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pce080

- 22. Yoshida, K., Toyama-Kato, Y., Kameda, K. and Kondo, T. (2003) Sepal Color Variation of Hydrangea macrophylla and Vacuolar pH Measured with a Proton-Selective Microelectrode. Plant and Cell Physiology, 44, 262-268. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcg033

- 23. Ohnishi, A., Fukada-Tanaka, S., Hoshino, A., Takada, J., Inagaki, Y. and Iida, S. (2005) Characterization of a Novel Na+/H+ Antiporter Gene InNHX2 and Comparison of InNHX2 with InNHX1, Which Is Responsible for Blue Flower Coloration by Increasing the Vacuolar pH in the Japanese Morning Glory. Plant and Cell Physiology, 46, 259-267. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pci028

- 24. Yoshida, K., Kawachi, M., Mori, M., Maeshima, M., Kondo, M., Nishimura, M. and Kondo, T. (2005) The Involvement of Tonoplast Proton Pumps and Na+(K+)/H+ Exchangers in the Change of Petal Color during Flower Opening of Morning Glory, Ipomoea tricolor cv. Heavenly Blue. Plant and Cell Physiology, 46, 407-415. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pci057

- 25. Quattrocchio, F., Verweij, W., Kroon, A., Spelt, C., Mol, J. and Koes, R. (2006) PH4 of Petunia Is an R2R3 MYB Protein That Activates Vacuolar Acidification through Interactions with Basic-Helix-Loop-Helix Tran-scription Factors of the Anthocyanin Pathway. The Plant Cell, 18, 1274-1291. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.034041

- 26. Momonoi, K., Yoshida, K., Mano, S., Takahashi, H., Nakamori, C., Shoji, K., Nitta, A. and Nishimura, M. (2009) A Vacuolar Iron Transporter in Tulip, TgVit1, Is Responsible for Blue Coloration in Petal Cells through Iron Accumulation. The Plant Journal, 59, 437-447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03879.x

- 27. Shoji, K., Momonoi, K. and Tsuji, T. (2010) Alternative Expression of Vacuolar Iron Transporter and Ferritin Genes Leads to Blue/Purple Coloration of Flowers in Tulip cv. “Murasakizuisho”. Plant and Cell Physiology, 51, 215-224. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcp181

- 28. Winkel-Shirley, B. (2001) It Takes a Garden. How Work on Diverse Plant Species Has Contributed to an Understanding of Flavonoid Metabolism. Plant Physiology, 127, 1399-1404. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.010675

- 29. 祝志欣, 鲁迎青. 花青素代谢途径与植物颜色变异[J]. 植物学报, 2016, 51(1): 107-119.

- 30. Winkel-Shirley, B. (1999) Evidence for Enzyme Complexes in the Phenylpropanoid and Flavonoid Pathways. Physi-ologia Plantarum, 107, 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3054.1999.100119.x

- 31. Guan, S. and Lu, Y.Q. (2013) Dis-secting Organ-Specific Transcriptomes through RNA-Sequencing. Plant Methods, 9, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-9-42

- 32. Davies, K.M. and Schwinn, K.E. (2003) Transcriptional Regulation of Secondary Metabolism. Functional Plant Biology, 30, 913-925. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP03062

- 33. Koes, R., Verweij, W. and Qua-ttrocchio, F. (2005) Flavonoids: A Colorful Model for the Regulation and Evolution of Biochemical Pathways. Trends in Plant Science, 10, 236-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2005.03.002

- 34. Feller, A., Machemer, K., Braun, E.L. and Grotewold, E. (2011) Evolutionary and Comparative Analysis of MYB and bHLH Plant Transcription Factors. The Plant Journal, 66, 94-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04459.x

- 35. Hichri, I., Barrieu, F., Bogs, J., Kappel, C., Delrot, S. and Lauvergeat, V. (2011) Recent Advances in the Transcriptional Regulation of the Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway. Journal of Experimental Botany, 62, 2465-2483. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq442

- 36. Petroni, K. and Tonelli, C. (2011) Recent Advances on the Regulation of Anthocyanin Synthesis in Reproductive Organs. Plant Science, 181, 219-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.009

- 37. Patra, B., Schluttenhofer, C., Wu, Y.M., Pattanaik, S. and Yuan, L. (2013) Transcriptional Regulation of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis in Plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, 1829, 1236- 1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.09.006

- 38. Xu, W.J., Dubos, C. and Lepiniec, L. (2015) Transcriptional Control of Flavonoid Biosynthesis by MYB-bHLH-WDR Complexes. Trends in Plant Science, 20, 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2014.12.001

- 39. Ramsay, N.A. and Glover, B.J. (2005) MYB-bHLH-WD40 Protein Complex and the Evolution of Cellular Diversity. Trends in Plant Science, 10, 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.011

- 40. Wang, H.L., Guan, S., Zhu, Z.X., Wang, Y. and Lu, Y.Q. (2013) A Valid Strategy for Precise Identifications of Transcription Factor Binding Sites in Combinatorial Regulation Using Bioinformatic and Ex-perimental Approaches. Plant Methods, 9, 34-45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-9-34

- 41. Zhu, Z.X., Wang, H.L., Wang, Y.T., Guan, S., Wang, F., Tang, J.Y., Zhang, R.J., Xie, L.L. and Lu, Y.Q. (2015) Characterization of the cis Elements in the Proximal Promoter Regions of the Anthocyanin Pathway Genes Reveals a Common Regulatory Logic That Governs Pathway Regulation. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66, 3775-3789. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erv173

- 42. Mol, J., Grotewold, E. and Koes, R. (1998) How Genes Paint Flowers and Seeds. Trends in Plant Science, 3, 212-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01242-4

- 43. Morohashi, K., Casas, M.I., Ferreyra, L.F., Mejia-Guerra, M.K., Pourcel, L., Yilmaz, A., Feller, A., Carvalho, B., Emiliani, J., Rodriguez, E., Pellegrinet, S., McMullen, M., Casati, P. and Grotewold, E. (2012) A Genome-Wide Regulatory Framework Identifies Maize Pericarp Color1 Controlled Genes. The Plant Cell, 24, 2745-2764. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.112.098004

- 44. Stracke, R., Ishihara, H., Barsch, G.H.A., Mehrtens, F., Niehaus, K. and Weisshaar, B. (2007) Differential Regulation of Closely Related R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors Controls Flavonol Accumulation in Different Parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana Seedling. The Plant Journal, 50, 660-677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03078.x

- 45. Rausher, M.D. (2006) The Evolution of Flavonoids and Their Genes. In: Grotewold, E., Ed., The Science of Flavonoids, Springer, New York, 175-211. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-28822-2_7

- 46. Ngaki, M.N., Louie, G.V., Philippe, R.N., Manning, G., Pojer, F., Bowman, M.E., Li, L., Larsen, E., Wurtele, E.S. and Noel, J.P. (2012) Evolution of the Chalcone-Isomerase Fold from Fatty-Acid Binding to Stereospecific Catalysis. Nature, 485, 530-533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11009

- 47. Markham, K.R. (1988) Distribution of Flavonoids in the Lower Plants and Its Evolutionary Significance. In: Harborne, J.B., Ed., The Flavonoids, Chapman and Hall, London, 427-468. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2913-6_12

- 48. Timberlake, C.F. and Bridle, P. (1980) The Anthocyanins. In: Harborne, J.B., Mabry, T.J. and Mabry, H., Eds., The Flavonoids, Academic Press, New York, 214-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2909-9_5

- 49. Niemann, G.J. (1988) Distribution and Evolution of the Flavonoids in Gym-nosperms. In: Harborne, J.B., Ed., The Flavonoids, Chapman and Hall, London, 469-478. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2913-6_13

- 50. Schwinn, K., Venail, J., Shang, Y.J., Mackay, S., Alm, V., Butelli, E., Oyama, R., Bailey, P., Davies, K. and Martin, C. (2006) A Small Family of MYB-Regulatory Genes Controls Floral Pigmentation Intensity and Patterning in the Genus Antirrhinum. The Plant Cell, 18, 831-851. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.039255

- 51. Whibley, A.C., Langlade, N.B., Andalo, C., Hanna, A.I., Bangham, A., Thebaud, C. and Coen, E. (2006) Evolutionary Paths Underlying Flower Color Variation in Antirrhinum. Science, 313, 963-966. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1129161

- 52. Cooley, A.M., Modliszewski, J.L., Rommel, M.L. and Willis, J.H. (2011) Gene Duplication in Mimulus Underlies Parallel Floral Evolution via Independent Trans-Regulatory Changes. Current Biology, 21, 700-704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.028

- 53. Hopkins, R. and Rausher, M.D. (2011) Identification of Two Genes Causing Reinforcement in the Texas Wildflower Phlox drummondii. Nature, 469, 411-414. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09641

- 54. Streisfeld, M.A., Young, W.N. and Sobel, J.M. (2013) Divergent Selection Drives Genetic Differentiation in an R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor That Contributes to Incipient Speciation in Mimulus aurantiacus. PLoS Genetics, 9, e1003385. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003385

- 55. Yuan, Y.W., Sagawa, J.M., Young, R.C., Christensen, B.J. and Bradshaw Jr., H.D. (2013) Genetic Dissection of a Major Anthocyanin QTL Contributing to Pollinator-Mediated Reproductive Isolation between Sister Species of Mimulus. Genetics, 194, 255-263. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.146852

- 56. Saito, N., Tatsuzawa, F., Yoda, K., Yokoi, M., Kasahara, K., Iida, S., Shigihara, A. and Honda, T. (1995) Acylated Cyanidin Glycosides in the Violet-Blue Flowers of Ipomoea purpurea. Phytochemistry, 40, 1283-1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(95)00369-I

- 57. Saito, N., Tatsuzawa, F., Yokoi, M., Kasahara, K., Iida, S., Shigihara, A. and Honda, T. (1996) Acylated Pelargonidin Glycosides in Red-Purple Flowers of Ipomoea purpurea. Phytochemistry, 43, 1365-1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00501-8

- 58. Lu, Y.Q., Du, J., Tang, J.Y., Wang, F., Zhang, J., Huang, J.X., Liang, W.F. and Wang, L.S. (2009) Environmental Regulation of Floral Anthocyanin Synthesis in Ipomoea purpurea. Molecular Ecology, 18, 3857-3871. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04288.x

- 59. Hoshino, A., Morita, Y., Choi, J.D., Saito, N., Toki, K., Tanaka, Y. and Iida, S. (2003) Spontaneous Mutations of the Flavonoid 3’-Hydroxylase Gene Conferring Reddish Flowers in the Three Morning Glory Species. Plant and Cell Physiology, 44, 990-1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcg143

- 60. Zufall, R.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2003) The Genetic Basis of a Flower Color Polymorphism in the Common Morning Glory (Ipomoea purpurea). Journal of Heredity, 94, 442-448. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esg098

- 61. Hunter, D.A., Fletcher, J.D., Davies, K.M. and Zhang, H. (2011) Colour Break in Reverse Bicolour Daffodils Is Associated with the Presence of Narcissus mosaic virus. Virology Journal, 8, 412. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-412

- 62. Habu, Y., Hisatomi, Y. and Iida, S. (1998) Molecular Characterization of the Mutable Flaked Allele for Flower Variegation in the Common Morning Glory. The Plant Journal, 16, 371-376. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00308.x

- 63. Abe, Y., Hoshino, A. and Iida, S. (1997) Appearance of Flower Varie-gation in the Mutable Speckled Line of the Japanese Morning Glory Is Controlled by Two Genetic Elements. Genes and Genetic Systems, 72, 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1266/ggs.72.57

- 64. Ohno, S., Hosokawa, M., Hoshino, A., Kitamura, Y., Morita, Y., Park, K.I., Nakashima, A., Deguchi, A., Tatsuzawa, F., Doi, M., Iida, S. and Yazawa, S. (2011) A bHLH Transcription Factor, DvIVS, Is Involved in Regu-lation of Anthocyanin Synthesis in Dahlia (Dahlia variabilis). Journal of Experimental Botany, 62, 5105-5116. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/err216

- 65. Saito, R., Fukuta, N., Ohmiya, A., Itoh, Y., Ozeki, Y., Kuchitsu, K. and Nakayama, M. (2006) Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Involved in the Formation of Marginal Picotee Petals in Petunia. Plant Science, 170, 828-834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.12.003

- 66. Ohno, S., Hosokawa, M., Kojima, M., Kitamura, Y., Hoshino, A., Tatsuzawa, F., Doi, M. and Yazawa, S. (2011) Simultaneous Post-Transcriptional Gene Silencing of Two Different Chalcone Synthase Genes Resulting in Pure White Flowers in the Octoploid Dahlia. Planta, 234, 945-958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-011-1456-2

- 67. Koseki, M., Goto, K., Masuta, C. and Kanazawa, A. (2005) The Star-Type Color Pattern in Petunia hybrida “Red star” Flowers Is Induced by Sequence-Specific Degradation of Chalcone Synthase RNA. Plant and Cell Physiology, 46, 1879-1883. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pci192

- 68. Schlangen, K., Miosic, S., Castro, A., Freudmann, K., Luczkiewicz, M., Vitzthum, F., Schwab, W., Gamsjäger, S., Musso, M. and Halbwirth, H. (2009) Formation of UV-Honey Guides in Rudbeckia hirta. Phytochemistry, 70, 889-898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.04.017

- 69. Davies, K.M., Albert, N.W. and Schwinn, K.E. (2012) From Landing Lights to Mimicry: The Molecular Regulation of Flower Colouration and Mechanisms for Pigmentation Patterning. Functional Plant Biology, 39, 619-638. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP12195

- 70. Wang, L., Albert, N.W., Zhang, H., Arathoon, S., Boase, M. R., Ngo, H., Schwinn, K.E., Davies, K.M. and Lewis, D.H. (2014) Temporal and Spatial Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Provide Diverse Flower Colour Intensities and Patterning in Cymbidium Orchid. Planta, 240, 983-1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-014-2152-9

- 71. Yamagishi, M. (2016) A Novel R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Regulates Light-Mediated Floral and Vegetative Anthocyanin Pigmentation Patterns in Lilium regale. Molecular Breeding, 36, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-015-0426-y

- 72. Martins, T.R., Berg, J.J., Blinka, S., Rausher, M.D. and Baum, D.A. (2013) Precise Spatio-Temporal Regulation of the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway Leads to Petal Spot Formation in Clarkia gracilis (Onagraceae). New Phytologist, 197, 958-969. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12062

- 73. Hsu, C.C., Chen, Y.Y., Tsai, W.C., Chen, W.H. and Chen, H.H. (2015) Three R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors Regulate Distinct Floral Pigmentation Patterning in Phalae-nopsis spp. Plant Physiology, 168, 175-191. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.254599

- 74. Yamagishi, M. (2013) How Genes Paint Lily Flowers: Regulation of Colouration and Pigmentation Patterning. Scientia Horticulturae, 163, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2013.07.024

- 75. Zufall, R.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2004) Genetic Changes Associated with Floral Adaptation Restrict Future Evolutionary Potential. Nature, 428, 847-850. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02489

- 76. Streisfeld, M.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2009) Genetic Changes Contributing to the Parallel Evolution of Red Floral Pigmentation among Ipomoea Species. New Phytologist, 183, 751-763. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02929.x

- 77. Des Marais, D.L. and Rausher, M.D. (2010) Parallel Evolution at Mul-tiple Levels in the Origin of Hummingbird Pollinated Flowers in Ipomoea. Evolution, 64, 2044-2054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00972.x

- 78. Smith, S.D. and Rausher, M.D. (2011) Gene Loss and Parallel Evolution Contribute to Species Difference in Flower Color. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 28, 2799-2810. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr109

- 79. Smith, S.D., Wang, S. and Rausher, M.D. (2013) Functional Evolution of an An-thocyanin Pathway Enzyme during a Flower Color Transition. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30, 602-612. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss255

- 80. Wessinger, C.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2014) Predictability and Irreversibility of Genetic Changes Associated with Flower Color Evolution in Penstemon barbatus. Evolution, 68, 1058-1070. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12340

- 81. Wessinger, C.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2015) Ecological Transition Predictably Associated with Gene Degeneration. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32, 347-354. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu298

- 82. Snowden, K.C. and Napoli, C.A. (1998) Psl: A Novel Spm-Like Transposable Element from Petunia hybrida. The Plant Journal, 14, 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00098.x

- 83. Chen, S., Matsubara, K., Kokubun, H., Kodama, H., Watanabe, H., Marchesi, E. and Ando, T. (2007) Reconstructing Historical Events That Occurred in the Petunia Hf1 Gene, Which Governs Anthocyanin Biosynthesis, and Effects of Artificial Selection by Breeding. Breeding Science, 57, 203-211. https://doi.org/10.1270/jsbbs.57.203

- 84. Nakatsuka, T., Nishihara, M., Mishiba, K., Hirano, H. and Yamamura, S. (2006) Two Different Transposable Elements Inserted in Flavonoid 3’,5’-Hydroxylase Gene Contribute to Pink Flower Coloration in Gentiana scabra. Molecular Genetics and Genomics, 275, 231-241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-005-0083-7

- 85. Ishiguro, K., Taniguchi, M. and Tanaka, Y. (2012) Functional Analysis of Antirrhinum kelloggii Flavonoid 3’-Hydroxylase and Flavonoid 3’,5’-Hydroxylase Genes; Critical Role in Flower Color and Evolution in the Genus Antirrhinum. Journal of Plant Research, 125, 451-456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-011-0455-5

- 86. Takahashi, R., Githiri, S.M., Hatayama, K., Dubouzet, E.G., Shimada, N., Aoki, T., Ayabe, S.I., Iwashina, T., Toda, K. and Matsumura, H. (2007) A Single-Base Deletion in Soybean Flavonol Synthase Gene Is Associated with Magenta Flower Color. Plant Molecular Biology, 63, 125-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-006-9077-z

- 87. Wessinger, C.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2012) Lessons from Flower Colour Evo-lution on Targets of Selection. Journal of Experimental Botany, 63, 5741-5749. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers267

- 88. Streisfeld, M.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2010) Population Genetics, Pleiotropy, and the Preferential Fixation of Mutations during Adaptive Evolution. Evolution, 65, 629-642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01165.x

- 89. Inagaki, Y., Hisatomi, Y., Suzuki, T., Kasahara, K. and Iida, S. (1994) Isolation of a Suppressor-mutator/Enhancer- Like Transposable Element, Tpn1, from Japanese Morning Glory Bearing Variegated Flowers. The Plant Cell, 6, 375- 383. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.6.3.375

- 90. Clegg, M.T. and Durbin, M.L. (2000) Flower Color Variation: A Model for the Experimental Study of Evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97, 7016-7023. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.13.7016

- 91. Iida, S., Morita, Y., Choi, J.D., Park, K.I. and Hoshino, A. (2004) Genetics and Epigenetics in Flower Pigmentation Associated with Transposable Elements in Morning Glories. Advances in Biophysics, 38, 141-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-227X(04)80136-9

- 92. Sobel, J.M. and Streisfeld, M.A. (2013) Flower Color as a Model System for Studies of Plant Evo-Devo. Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00321

- 93. Coberly, L.C. and Rausher, M.D. (2003) Analysis of a Chalcone Synthase Mutant in Ipomoea purpurea Reveals a Novel Function for Flavonoids: Amelioration of Heat Stress. Molecular Ecology, 12, 1113-1124. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01786.x

- 94. Coberly, L.C. and Rausher, M.D. (2008) Pleiotropic Effects of an Allele Producing White Flowers in Ipomoea purpurea. Evolution, 62, 1076-1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00355.x

- 95. Dick, C.A., Buenrostro, J., Butler, T., Carlson, M.L., Kliebenstein, D.J. and Whittall, J.B. (2011) Arctic Mustard Flower Color Polymorphism Controlled by Petal-Specific Downregulation at the Threshold of the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway. PLoS ONE, 6, e18230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018230

- 96. Nishihara, M., Yamada, E., Saito, M., Fujita, K., Takahashi, H. and Nakatsuka, T. (2014) Molecular Characterization of Mutations in White-Flowered Torenia Plants. BMC Plant Biology, 14, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-14-86

- 97. Quattrocchio, F., Wing, J., van der Woude, K., Souer, E., de Vetten, N., Mol, J. and Koes, R. (1999) Molecular Analysis of the anthocyanin2 Gene of Petunia and Its Role in the Evolution of Flower Color. The Plant Cell, 11, 1433-1444. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.11.8.1433

- 98. Chang, S.M., Lu, Y.Q. and Rausher, M.D. (2005) Neutral Evolution of the Non-binding Region of the Anthocyanin Regulatory Gene Ipmyb1 in Ipomoea. Genetics, 170, 1967-1978. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.034975

- 99. Morita, Y., Saitoh, M., Hoshino, A., Nitasaka, E. and Iida, S. (2006) Isolation of cDNAs for R2R3-MYB, bHLH and WDR Transcriptional Regulators and Identification of c and ca Mutations Conferring White Flowers in the Japanese Morning Glory. Plant and Cell Physiology, 47, 457-470. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcj012

- 100. Whittall, J.B., Voelckel, C., Kliebenstein, D.J. and Hodges, S.A. (2006) Convergence, Constraint and the Role of Gene Expression during Adaptive Radiation: Floral Anthocyanins in Aquilegia. Molecular Ecology, 15, 4645-4657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03114.x

- 101. Yamagishi, M. (2011) Oriental Hybrid Lily Sorbonne Homologue of LhMYB12 Regulates Anthocyanin Biosyntheses in Flower Tepals and Tepal Spots. Molecular Breeding, 28, 381-389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-010-9490-5

- 102. Nishijima, T., Morita, Y., Sasaki, K., Nakayama, M., Yamaguchi, H., Ohtsubo, N., Niki, T. and Niki, T. (2013) A Torenia (Torenia fournieri Lind. ex Fourn.) Novel Mutant “Flecked” Produces Variegated Flowers by Insertion of a DNA Transposon into an R2R3-MYB Gene. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 82, 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs1.82.39

- 103. Yuan, Y.W., Sagawa, J.M., Frost, L., Vela, J.P. and Bradshaw Jr., H.D. (2014) Tran-scriptional Control of Floral Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Monkeyflowers (Mimulus). New Phytologist, 204, 1013-1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12968

- 104. Park, K.I., Choi, J.D., Hoshino, A., Morita, Y. and Iida, S. (2004) An Intragenic Tandem Duplication in a Transcriptional Regulatory Gene for Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Confers Pale-Colored Flowers and Seeds with Fine Spots in Ipomoea tricolor. The Plant Journal, 38, 840-849. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02098.x

- 105. Park, K.I., Ishikawa, N., Morita, Y., Choi, J.D., Hoshino, A. and Iida, S. (2007) A bHLH Regulatory Gene in the Common Morning Glory, Ipomoea purpurea, Controls Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Flowers, Proanthocyanidin and Phytomelanin Pigmentation in Seeds, and Seed Trichome Formation. The Plant Journal, 49, 641-654. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02988.x

- 106. Albert, N.W., Lewis, D.H., Zhang, H., Schwinn, K.E., Jameson, P.E. and Davies, K.M. (2011) Members of an R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Family in Petunia Are Developmentally and Environ-mentally Regulated to Control Complex Floral and Vegetative Pigmentation Patterning. The Plant Journal, 65, 771-784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04465.x

- 107. Albert, N.W., Griffiths, A.G., Cousins, G.R., Verry, I.M. and Williams, W.M. (2015) Anthocyanin Leaf Markings Are Regulated by a Family of R2R3-MYB Genes in the Genus Trifolium. New Phytologist, 205, 882-893. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13100

- 108. Rausher, M.D., Miller, R.E. and Tiffin, P. (1999) Patterns of Evolutionary Rate Variation Among Genes of the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 266-274. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026108

- 109. Lu, Y.Q. and Rausher, M.D. (2003) Evolutionary Rate Variation in Anthocyanin Pathway Genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 20, 1844-1853. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msg197

- 110. Streisfeld, M.A. and Rausher, M.D. (2007) Relaxed Constraint and Evolutionary Rate Variation between Basic Helix- Loop-Helix Floral Anthocyanin Regulators in Ipomoea. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24, 2816-2826. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm216

- 111. Streisfeld, M.A., Liu, D. and Rausher, M.D. (2011) Predictable Patterns of Con-straint among Anthocyanin-Regulating Transcription Factors in Ipomoea. New Phytologist, 191, 264-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03671.x

- 112. Yamagishi, M., Yoshida, Y. and Nakayama, M. (2012) The Transcription Factor LhMYB12 Determines Anthocyanin Pigmentation in the Tepals of Asiatic Hybrid Lilies (Lilium spp.) and Regulates Pigment Quantity. Molecular Breeding, 30, 913-925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-011-9675-6

- 113. Hopkins, R. and Rausher, M.D. (2012) Pollinator-Mediated Selection on Flower Color Allele Drives Reinforcement. Science, 335, 1090-1092. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1215198

- 114. Tateishi, N., Ozaki, Y. and Okubo, H. (2010) White Marginal Picotee Formation in the Petals of Camellia japonica “Tamanoura”. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 79, 207-214. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs1.79.207

- 115. Kanazawa, A., Inaba, J.-I., Shimura, H., Otagaki, S., Tsukahara, S., Matsuzawa, A., Kim, B.M., Goto, K. and Masuta, C. (2011) Virus-Mediated Efficient Induction of Epigenetic Modifications of Endogenous Genes with Phenotypic Changes in Plants. The Plant Journal, 65, 156-168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04401.x

- 116. Morita, Y., Saito, R., Ban, Y., Tanikawa, N., Kuchitsu, K., Ando, T., Yoshikawa, M., Habu, Y., Ozeki, Y. and Nakayama, M. (2012) Tandemly Arranged chalcone synthase A Genes Contribute to the Spatially Regulated Expression of siRNA and the Natural Bicolor Floral Phenotype in Petunia hybrida. The Plant Journal, 70, 739-749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04908.x

- 117. Durbin, M.L., McCaig, B. and Clegg, M.T. (2000) Molecular Evolution of the Chalcone Synthase Multigene Family in the Morning Glory Genome. Plant Molecular Biology, 42, 79-92. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006375904820

- 118. Clegg, M.T. and Durbin, M.L. (2003) Tracing Floral Adaptations from Ecology to Molecules. Nature Reviews Genetics, 4, 206-215. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1023

- 119. Durbin, M.L., Lundy, K.E., Morrell, P.L., Torres-Martinez, C.L. and Clegg, M.T. (2003) Genes that Determine Flower Color: The Role of Regulatory Changes in the Evolution of Phenotypic Adaptations. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 29, 507-518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00196-9

- 120. Glover, B.J., Walker, R.H., Moyroud, E. and Brockington, S.F. (2013) How to Spot a Flower. New Phytologist, 197, 687-689. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12112

- 121. Zhang, Y., Cheng, Y., Ya, H., Xu, S. and Han, J. (2015) Transcriptome Sequencing of Purple Petal Spot Region in Tree Peony Reveals Differentially Expressed Anthocyanin Structural Genes. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 964. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00964

- 122. Li, Q., Wang, J., Sun, H.Y. and Shang, X. (2014) Flower Color Patterning in Pansy (Viola × wittrockiana Gams.) Is Caused by the Differential Expression of Three Genes from the Anthocyanin Pathway in Acyanic and Cyanic Flower Areas. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 84, 134-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.09.012

- 123. Yamagishi, M., Shimoyamada, Y., Nakatsuka, T. and Masuda, K. (2010) Two R2R3-MYB Genes, Homologs of Petunia AN2, Regulate Anthocyanin Biosyntheses in Flower Tepals, Tepal Spots and Leaves of Asiatic Hybrid Lily. Plant and Cell Physiology, 51, 463-474. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcq011

- 124. Shang, Y., Venail, J., Mackay, S., Bailey, P.C., Schwinn, K.E., Jameson, P.E., Martin, C.R. and Davies, K.M. (2011) The Molecular Basis for Venation Patterning of Pigmentation and Its Effect on Pollinator Attraction in Flowers of Antirrhinum. New Phytologist, 189, 602-615. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03498.x

- 125. Telias, A., Lin-Wang, K., Stevenson, D.E., Cooney, J.M., Hellens, R.P., Allan, A.C., Hoover, E.E. and Bradeen, J.M. (2011) Apple Skin Patterning Is Associated with Differential Expression of MYB10. BMC Plant Biology, 11, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-11-93

- 126. Yamagishi, M., Toda, S. and Tasaki, K. (2014) The Novel Allele of the LhMYB12 Gene Is Involved in Splatter-Type Spot Formation on the Flower Tepals of Asiatic Hybrid Lilies (Lilium spp.). New Phytologist, 201, 1009-1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12572

- 127. Matsui, K., Umemura, Y. and Ohme-Takagi, M. (2008) AtMYBL2, a Protein with a Single MYB Domain, Acts as a Negative Regulator of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal, 55, 954-967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03565.x

- 128. Albert, N.W., Davies, K.M., Lewis, D.H., Zhang, H.B., Montefiori, M., Brendolise, C., Boase, M.R., Ngo, H., Jameson, P.E. and Schwinn, K.E. (2014) A Conserved Network of Transcriptional Activators and Repressors Regulates Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Eudicots. The Plant Cell, 26, 962-980. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.122069

- 129. Shoji, K., Miki, N., Nakajima, N., Momonoi, K., Kato, C. and Yoshida, K. (2007) Perianth Bottom-Specific Blue Color Development in Tulip cv. Murasakizuisho Requires Ferric Ions. Plant and Cell Physiology, 48, 243-251. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcl060

- 130. Kay, K.M., Reeves, P.A., Olmstead, R.G. and Schemske, D.W. (2005) Rapid Speciation and the Evolution of Hummingbird Pollination in Neotropical Costus Subgenus Costus (Costaceae): Evidence from nrDNA ITS and ETS Sequences. American Journal of Botany, 92, 1899-1910. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.11.1899

- 131. Whittall, J.B. and Hodges, S.A. (2007) Pollinator Shifts Drive Increasingly Long Nectar Spurs in Columbine Flowers. Nature, 447, 706-709. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05857

- 132. Rausher, M.D. (2008) Evolutionary Transitions in Floral Color. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 169, 7-21. https://doi.org/10.1086/523358

- 133. Smith, S.D. and Goldberg, E.E. (2015) Tempo and Mode of Flower Color Evolution. American Journal of Botany, 102, 1014-1025. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500163

- 134. Perret, M., Chautems, A., Spichiger, R., Kite, G. and Savolainen, V. (2003) Systematics and Evolution of Tribe Sinningieae (Gesneriaceae): Evidence from Phylogenetic Analyses of Six Plastid DNA Regions and Nuclear ncpGS. American Journal of Botany, 90, 445-460. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.90.3.445

- 135. Armbruster, W.S. (2002) Can Indirect Selection and Genetic Context Contribute to Trait Diversification? A Transition- Probability Study of Blossom-Colour Evolution in Two Genera. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15, 468-486. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00399.x

- 136. Thomson, J.D. and Wilson, P. (2008) Explaining Evolutionary Shifts between Bee and Hummingbird Pollination: Convergence, Divergence, and Directionality. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 169, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1086/523361

- 137. Schemske, D.W. and Bradshaw, H.D. (1999) Pollinator Preference and the Evolution of Floral Traits in Monkeyflowers (Mimulus). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96, 11910-11915. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.21.11910

- 138. Bradshaw, H.D. and Schemske, D.W. (2003) Allele Substitution at a Flower Colour Locus Produces a Pollinator Shift in Monkeyflowers. Nature, 426, 176-178. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02106

- 139. Streisfeld, M.A. and Kohn, J.R. (2007) Environment and Pollinator-Mediated Selection on Parapatric Floral Races of Mimulus aurantiacus. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 20, 122-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01216.x

- 140. Hoballah, M.E., Gübitz, T., Stuurman, J., Broger, L., Barone, M., Mandel, T., Dell’Olivo, A., Arnold, M. and Kuhlemeier, C. (2007) Single Gene-Mediated Shift in Pollinator Attraction in Petunia. The Plant Cell, 19, 779-790. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.048694

- 141. Melendez-Ackerman, E. and Campbell, D.R. (1998) Adaptive Significance of Flower Color and Inter-Trait Correlations in an Ipomopsis Hybrid Zone. Evolution, 52, 1293-1303. https://doi.org/10.2307/2411299

- 142. Bischoff, M., Raguso, R.A., Jurgens, A. and Campbell, D.R. (2015) Context-Dependent Reproductive Isolation Mediated by Floral Scent and Color. Evolution, 69, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12558

- 143. Hopkins, R. and Rausher, M.D. (2014) The Cost of Reinforcement: Selection on Flower Color in Allopatric Populations of Phlox drummondii. The American Naturalist, 183, 693-710. https://doi.org/10.1086/675495

- 144. Caruso, C.M., Scott, S.L., Wray, J.C. and Walsh, C.A. (2010) Pollinators, Herbivores, and the Maintenance of Flower Color Variation: A Case Study with Lobelia siphilitica. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 171, 1020-1028. https://doi.org/10.1086/656511

- 145. Renoult, J.P., Thomann, M., Schaefer, H.M. and Cheptou, P.O. (2013) Selection on Quan-titative Colour Variation in Centaurea cyanus: The Role of the Pollinator’s Visual System. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 26, 2415-2427. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12234

- 146. Sletvold, N., Trunschke, J., Smit, M., Verbeek, J. and Ågren, J. (2016) Strong Pollina-tor-Mediated Selection for Increased Flower Brightness and Contrast in a Deceptive Orchid. Evolution, 70, 716-724. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12881

- 147. Waser, N.M. and Price, M.V. (1985) The Effect of Nectar Guides on Pollinator Prefe-rence: Experimental Studies with a Montane Herb. Oecologia, 67, 121-126. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00378462

- 148. Johnson, S.D. and Dafni, A. (1998) Response of Bee-Flies to the Shape and Pattern of Model Flowers: Implications for Floral Evolution in a Mediterranean Herb. Functional Ecology, 12, 289-297. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00175.x

- 149. van Kleunen, M., Nänni, I., Donaldson, J.S. and Manning, J.C. (2007) The Role of Beetle Marks and Flower Colour on Visitation by Monkey Beetles (Hopliini) in the Greater Cape Floral Region, South Africa. Annals of Botany, 100, 1483-1489. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcm256

- 150. Medel, R., Botto-Mahan, C. and Ka-lin-Arroyo, M. (2003) Pollinator-Mediated Selection on the Nectar Guide Phenotype in the Andean Monkey Flower, Mimulus luteus. Ecology, 84, 1721-1732. https://doi.org/10.1890/01-0688

- 151. Hansen, D.M., Van der Niet, T. and Johnson, S.D. (2012) Floral Signposts: Testing the Significance of Visual “Nectar Guides” for Pollinator Behaviour and Plant Fitness. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 279, 634- 639. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.1349

- 152. de Jager, M.L. and Ellis, A.G. (2014) Floral Polymorphism and the Fitness Implications of Attracting Pollinating and Florivorous Insects. Annals of Botany, 113, 213-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mct189

- 153. Jones, K.N. and Reithel, J.S. (2001) Pollinator-Mediated Selection on a Flower Color Polymorphism in Experimental Populations of Antirrhinum (Scrophulariaceae). American Journal of Botany, 88, 447-454. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657109

- 154. Parachnowitsch, A.L. and Kessler, A. (2010) Pollinators Exert Natural Selection on Flower Size and Floral Display in Penstemon digitalis. New Phytologist, 188, 393-402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03410.x

- 155. Campbell, D.R. and Bischoff, M. (2013) Selection for a Floral Trait Is Not Mediated by Pollen Receipt Even though Seed Set in the Population Is Pollen-Limited. Functional Ecology, 27, 1117-1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12131

- 156. Lavi, R. and Sapir, Y. (2015) Are Pollinators the Agents of Selection for the Extreme Large Size and Dark Color in Oncocyclus Irises? New Phytologist, 205, 369-377. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12982

- 157. Miller, R.B. (1981) Hawkmoths and the Geographic Patterns of Floral Variation in Aquilegia caerulea. Evolution, 35, 763-774. https://doi.org/10.2307/2408246

- 158. Brunet, J. (2009) Pollinators of the Rocky Mountain Columbine: Temporal Variation, Functional Groups and Associations with Floral Traits. Annals of Botany, 103, 1567-1578. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcp096

- 159. Grossenbacher, D.L. and Stanton, M.L. (2014) Pollinator-Mediated Competition In-fluences Selection for Flower-Color Displacement in Sympatric Monkeyflowers. American Journal of Botany, 101, 1915-1924. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1400204

- 160. Levin, D.A. (1970) The Exploitation of Pollinators by Species and Hybrids of Phlox. Evolution, 24, 367-377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2406811

- 161. Levin, D.A. (1985) Reproductive Character Displacement in Phlox. Evolution, 39, 1275-1281. https://doi.org/10.2307/2408784

- 162. Muchhala, N., Johnsen, S. and Smith, S.D. (2014) Competition for Hummingbird Pollina-tion Shapes Flower Color Variation in Andean Solanaceae. Evolution, 68, 2275-2286. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12441

- 163. Waser, N.M. and Price, M.V. (1981) Pollinator Choice and Stabilizing Selection for Flower Color in Delphinium nelsonii. Evolution, 35, 376-390. https://doi.org/10.2307/2407846

- 164. Jones, K.N. (1996) Pollinator Behavior and Post-Pollination Reproductive Success in Alternative Floral Phenotypes of Clarkia gracilis (Onagraceae). International Journal of Plant Sciences, 157, 593-599. https://doi.org/10.1086/297396

- 165. Frey, F.M. (2004) Opposing Natural Selection from Herbivores and Pathogens May Maintain Floral-Color Variation in Claytonia virginica (Portulacaceae). Evolution, 58, 2426-2437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00872.x

- 166. Frey, F.M., Dunton, J. and Garland, K. (2011) Floral Color Variation and Associations with fitness-Related Traits in Malva moschata (Malvaceae). Plant Species Biology, 26, 235-243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-1984.2011.00325.x

- 167. Tastard, E., Ferdy, J.B., Burrus, M., Thebaud, C. and Andalo, C. (2012) Patterns of Floral Colour Neighbourhood and Their Effects on Female Reproductive Success in an Antirrhinum Hybrid Zone. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 25, 388-399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02433.x

- 168. Arista, M., Talavera, M., Berjano, R. and Ortiz, P.L. (2013) Abiotic Factors May Explain the Geographical Distribution of Flower Colour Morphs and the Maintenance of Colour Polymorphism in the Scarlet Pimpernel. Journal of Ecology, 101, 1613-1622. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12151

- 169. Joseph, N. and Siril, E.A. (2013) Floral Color Polymorphism and Reproductive Success in Annatto (Bixa orellana L.). Tropical Plant Biology, 6, 217-227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12042-013-9128-y

- 170. Ortiz, P.L., Berjano, R., Talavera, M., Rodriguez-Zayas, L. and Arista, M. (2015) Flower Colour Polymorphism in Lysimachia arvensis: How Is the Red Morph Maintained in Mediterranean Environments? Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 17, 142-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2015.01.004

- 171. Sobral, M., Veiga, T., Dominguez, P., Guitian, J.A., Guitian, P. and Guitian, J.M. (2015) Selective Pressures Explain Differences in Flower Color among Gentiana lutea Populations. PLoS ONE, 10, e0132522. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132522

- 172. Veiga, T., Guitian, J., Guitian, P., Guitian, J. and Sobral, M. (2015) Are Pollinators and Seed Predators Selective Agents on Flower Color in Gentiana lutea? Evolutionary Ecology, 29, 451-464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-014-9751-6

- 173. Fry, J.D. and Rausher, M.D. (1997) Selection on a Floral Color Polymorphism in the Tall Morning Glory (Ipomoea purpurea): Transmission Success of the Alleles through Pollen. Evolution, 51, 66-78. https://doi.org/10.2307/2410961

- 174. Mojonnier, L.E. and Rausher, M.D. (1997) Selection on a Floral Color Polymorphism in the Common Morning Glory (Ipomoea purpurea): The Effects of Overdominance in Seed Size. Evolution, 51, 608-614. https://doi.org/10.2307/2411133

- 175. Malerba, R. and Nattero, J. (2012) Pollinator Response to Flower Color Polymorphism and Floral Display in a Plant with a Single-Locus Floral Color Polymorphism: Consequences for Plant Reproduction. Ecological Research, 27, 377-385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-011-0908-2

- 176. Takahashi, Y., Takakura, K. and Kawata, M. (2015) Flower Color Polymorphism Maintained by Overdominant Selection in Sisyrinchium sp. Journal of Plant Research, 128, 933-939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-015-0750-7

- 177. Epperson, B.K. and Clegg, M.T. (1987) Frequency-Dependent Variation for Outcrossing Rate among Flower-Color Morphs of Ipomoea purpurea. Evolution, 41, 1302-1311. https://doi.org/10.2307/2409095

- 178. Rausher, M.D., Augustine, D. and Vanderkooi, A. (1993) Absence of Pollen Discounting in a Genotype of Ipomoea purpurea Exhibiting Increased Selfing. Evolution, 47, 1688-1695. https://doi.org/10.2307/2410213

- 179. Rausher, M.D. and Fry, J.D. (1993) Effects of a Locus Affecting Floral Pigmentation in Ipomoea purpurea on Female Fitness Components. Genetics, 134, 1237-1247.

- 180. Strauss, S.Y. and Whittall, J.B. (2006) Non-Pollinator Agents of Selection on Floral Traits. In: Harder, L.D. and Barrett, S.C.H., Eds., Ecology and Evolution of Flowers, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 120-138.

- 181. Johnson, M.T.J., Campbell, S.A. and Barrett, S.C.H. (2015) Evolutionary Interac-tions between Plant Reproduction and Defense against Herbivores. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46, 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054215

- 182. Fenster, C.B., Armbruster, W.S., Wilson, P., Dudash, M.R. and Thomson, J.D. (2004) Pollination Syndromes and Floral Specialization. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 35, 375-403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347

- 183. Kaczorowski, R.L., Gardener, M.C. and Holtsford, T.P. (2005) Nectar Traits in Nicotiana Section Alatae (Solanaceae) in Relation to Floral Traits, Pollinators, and Mating System. American Journal of Botany, 92, 1270-1283. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.8.1270

- 184. Frey, F.M. (2007) Phenotypic Integration and the Potential for Independent Color Evolution in a Polymorphic Spring Ephemeral. American Journal of Botany, 94, 437-444. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.94.3.437

- 185. Wessinger, C.A., Hileman, L.C. and Rausher, M.D. (2014) Identification of Major Quantitative Trait Loci Underlying Floral Pollination Syndrome Divergence in Penstemon. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 369, Article ID: 20130349. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0349

- 186. Smith, S.D. (2016) Plei-otropy and the Evolution of Floral Integration. New Phytologist, 209, 80-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13583

- 187. Kingsolver, J.G., Hoekstra, H.E., Hoekstra, J.M., Berrigan, D., Vignieri, S.N., Hill, C.E., Hoang, A., Gibert, P. and Beerli, P. (2001) The Strength of Phenotypic Selection in Natural Populations. The American Naturalist, 157, 245-261. https://doi.org/10.1086/319193

- 188. Levin, D.A. and Brack, E.T. (1995) Natural-Selection against White Petals in Phlox. Evo-lution, 49, 1017-1022. https://doi.org/10.2307/2410423

- 189. Fehr, C. and Rausher, M.D. (2004) Effects of Variation at the Flower-Colour A Locus on Mating System Parameters in Ipomoea purpurea. Molecular Ecology, 13, 1839-1847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02182.x

- 190. Schemske, D.W. and Bierzychudek, P. (2001) Perspective: Evolution of Flower Color in the Desert Annual Linanthus parryae: Wright Revisited. Evolution, 55, 1269-1282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00650.x

- 191. Jones, K.N. (1996) Fertility Selection on a Discrete Floral Polymor-phism in Clarkia (Onagraceae). Evolution, 50, 71-79. https://doi.org/10.2307/2410781