Advances in Clinical Medicine

Vol.

11

No.

07

(

2021

), Article ID:

43695

,

10

pages

10.12677/ACM.2021.117426

血清唾液酸水平在淋巴瘤患者中的变化及意义

肖晶晶1,聂淑敏2,李田兰3,黄俊霞3,毛春霞3,高燕3,周静静3,冯献启3*

1青岛大学医学部,山东 青岛

2青岛大学附属医院神经内科,山东 青岛

3青岛大学附属医院血液科,山东 青岛

收稿日期:2021年6月5日;录用日期:2021年6月28日;发布日期:2021年7月6日

摘要

目的:探讨血清唾液酸(SA)水平在初治淋巴瘤患者中的变化及意义。方法:收集236例初治淋巴瘤患者临床特征参数,回顾性分析血清SA水平与淋巴瘤患者临床特征参数相关性及其对疗效和预后的影响。结果:与健康者比较,淋巴瘤患者血清SA水平显著升高(P < 0.05)。与治疗前比较,患者缓解后血清SA水平显著降低(P < 0.05)。与低SA组比较,高SA组患者具有侵袭性更强、分期更晚、危险度分层更高、更易贫血的特点,并且具有更高的LDH和ki-67水平,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。单因素分析结果示SA > 605 mg/L、年龄 > 60岁、贫血、LDH > 250 U/L、ki67 > 45%、高危危险度分层的淋巴瘤患者PFS显著缩短(P < 0.05),SA > 605 mg/L、年龄 > 60岁、贫血、LDH > 250 U/L、ki67 > 45%、高危危险度分层、侵袭性淋巴瘤患者OS显著缩短(P < 0.05)。多因素分析显示年龄是影响淋巴瘤患者PFS和OS的独立预后因素(P < 0.05)。高SA组患者总缓解率(ORR)、疾病控制率(DCR)显著低于低SA组患者(P < 0.05)。结论:与健康人比较,初治淋巴瘤患者血清SA水平明显升高;血清SA水平升高有助于预测淋巴瘤患者预后不良,以及判断疾病分期、疗效和预后。

关键词

淋巴瘤,唾液酸,肿瘤免疫逃逸,预后

Changes and Significance of Serum Sialic Acid Levels in Patients with Lymphoma

Jingjing Xiao1, Shumin Nie2, Tianlan Li3, Junxia Huang3, Chunxia Mao3, Yan Gao3, Jingjing Zhou3, Xianqi Feng3*

1Department of Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

2Department of Neurology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

3Department of Hematology, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

Received: Jun. 5th, 2021; accepted: Jun. 28th, 2021; published: Jul. 6th, 2021

ABSTRACT

Objective: To investigate the changes and significance of serum sialic acid (SA) levels in patients with new-diagnosed lymphoma. Methods: The clinical parameters of 236 patients with new-diagnosed lymphoma were collected, and the correlation between serum SA level and clinical parameters of lymphoma patients and its influence on efficacy and prognosis were retrospectively analyzed. Results: Compared with healthy subjects, serum SA levels were significantly increased in lymphoma patients (P < 0.05). Serum SA levels were significantly lower in patients after remission compared with those before treatment (P < 0.05). Compared with the low SA group, patients in the high SA group were characterized by more aggressive, more advanced stage, risk stratification, and more susceptibility to anemia, and had higher LDH and ki-67 levels, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Univariate analysis showed that PFS was significantly shorter in lymphoma patients with SA > 605 mg/L, age > 60 years, anemia, LDH > 250 U/L, ki67 > 45%, and risk stratification (P < 0.05), and OS was significantly shorter in lymphoma patients with SA > 605 mg/L, age > 60 years, anemia, LDH > 250 U/L, ki67 > 45%, risk stratification, and invasive lymphoma (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that age was an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS in lymphoma patients (P < 0.05). The overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) of patients in the high SA group were significantly lower than those of patients in the low SA group (P < 0.05). Conclusion: Compared with healthy individuals, serum SA levels were significantly increased in patients with primary lymphoma; elevated serum SA levels indicated a poor prognosis in patients with lymphoma and helped to determine disease stage, efficacy and prognosis.

Keywords:Lymphoma, Sialic Acid, Tumor Immune Escape, Prognosis

Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

SA是一种酸性九碳单糖,广泛存在于哺乳动物细胞表面 [1]。随着糖代谢组学领域的兴起,许多研究已经将糖蛋白作为癌症的生物标志物,蛋白质的功能激活需要翻译后修饰,糖基化是与恶性肿瘤相关最常见修饰,而唾液酸化是糖蛋白末端重要修饰,SA及其衍生物在细胞识别和通讯、糖代谢、介导细菌和病毒感染、参与肿瘤生长和转移等生理和病理过程中发挥重要作用 [1] [2]。细胞癌变后合成糖脂增加,细胞膜上糖脂转化异常并脱落或分泌入血,导致血清SA含量增加 [3]。在临床工作中我们发现淋巴瘤患者血清SA水平明显升高,但是国内外文献对血清SA水平在淋巴瘤中的变化及意义相关研究较少。因此本研究旨在探究血清SA水平与淋巴瘤患者临床特征参数相关性以及对疗效和预后的影响。

2. 资料与方法

2.1. 一般资料

选取青岛大学附属医院自2015年1月1日至2019年6月31日收治的初诊淋巴瘤患者320例。对合并近期炎症及感染性疾病、肺炎、慢性牙周炎、类风湿关节炎、糖尿病、肝炎、肝硬化、胰腺炎、脓毒症、颅内出血、肾病综合征、急性心肌梗死、食道癌、肺癌、口腔癌以及合并其他癌症的患者 [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] 予以排除。符合标准的淋巴瘤患者共236例:霍奇金淋巴瘤7例;非霍奇金淋巴瘤229例,包括弥漫大B细胞淋巴瘤(DLBCL)患者112例,非霍奇金淋巴瘤117例。236例淋巴瘤患者中,男性127例(53.8%),女性109例(46.2%);中位年龄59 (16~90)岁。同时随机抽取该院2019年1月1日至2019年6月1日体检健康者197例为健康对照组。我们对236例淋巴瘤患者随访时间为8~66个月,中位随访时间为35个月,随访时间截至2020年6月1日。血清SA采用酶法间接测定,由贝克曼库尔特AU5800全自动生化分析仪检测,试剂盒为浙江东瓯诊断公司提供。

本研究已通过青岛大学附属医院伦理委员会同意(审批号:QYFYWZLL26367)。

2.2. 恶性程度划分

临床中通常根据将NHL分为高度侵袭性淋巴瘤、侵袭性淋巴瘤及惰性淋巴瘤;本研究中,将高度侵袭性淋巴瘤和侵袭性淋巴瘤划分为侵袭性淋巴瘤;余分型归为惰性淋巴瘤。

2.3. 危险度分层标准

根据NCCN临床实践指南:非霍奇金淋巴瘤(2015.V2),将弥漫大B细胞淋巴瘤、外周T细胞淋巴瘤、结外NK/T细胞淋巴瘤(鼻型)的危险度分层分为低危、低/中危、中/高危、高危;滤泡性淋巴瘤、CLL/SCLL的危险度分层为低危、中危、高危。

2.4. 观察指标

收集淋巴瘤患者初诊时年龄、性别、血细胞计数(血红蛋白、血小板)、血清SA、LDH、病理活检等指标;血清LDH在临床上正常参考范围为120~250 U/L,将LDH > 250 U/L定义为高LDH组,LDH ≤ 250 U/L定义为低LDH组。

2.5. 疗效评价

根据恶性淋巴瘤的Cheson疗效判定标准 [9],近期疗效用完全缓解(CR)、部分缓解(PR)、疾病稳定(SD)、进展(PD),远期疗效采用PFS、OS进行评估。其中178例淋巴瘤患者接受4个周期化疗治疗。CR率加PR率、SD率等于疾病控制率(DCR);CR率加PR率等于总缓解率(ORR)。

2.6. 随访

所有患者均通过住院和电话随访,随访时间8~66个月,中位随访35个月,最后随访时间为2018年6月10日。总体生存期(OS)定义为从患者接受治疗的时间到患者死亡的时间。患者确诊淋巴瘤后,每月进行一次门诊或电话随访。随访至2020年6月1日,记录患者死亡事件发生、疾病复发及进展时间,计算患者PFS和OS时间。

2.7. 统计学处理

采用MedCal绘制ROC曲线;SPSS25.0统计软件进行统计学分析。计数资料的描述性分析应用例数和百分比(n, %)表示。计量资料根据正态性分析(F检验)结果,组间差异比较采用非参数检验(Mann-Whitney U检验)。两组间构成比的差异性分析采用χ2检验。配对样本采用Willcoxon符号秩和检验。单因素分析采用Kaplan-Meier法。多因素分析采用COX回归分析,P < 0.05示差异有统计学意义。

3. 结果

3.1. 淋巴瘤患者血清SA水平变化

本研究中,健康者197人,淋巴瘤患者236人;健康组血清SA水平与健康对照组比较,淋巴瘤患者的血清SA水平明显升高(P < 0.05) (表1)。

Table 1. Comparison of serum SA levels between lymphoma group and healthy group

表1. 淋巴瘤组与健康组血清SA水平比较

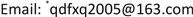

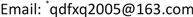

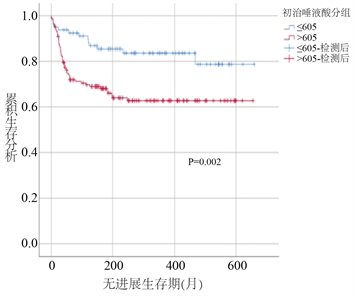

3.2. 确定血清SA最佳临界值与分组

采用Medcalc软件绘制血清SA的ROC曲线,根据受试者工作特征曲线(ROC曲线)将MM患者初次化疗前血清SA = 605 mg/L作为最佳临界值,其曲线下面积(AUC)为0.752,对应的敏感度为64.8%,特异度74.6% (图1),分为高SA组(SA > 605 mg/L)和低SA组(SA ≤ 605 mg/L);高NLR组和低NLR组患者分别有83和153例。

SA Ki-67

SA Ki-67

Figure 1. Optimal cut-off values of SA and Ki-67 in 236 lymphoma patients

图1. 236例淋巴瘤患者SA、Ki-67最佳临界值

3.3. 血清SA水平与临床特征参数相关性

比较高SA组与低SA组患者在性别、年龄等临床特征方面组间有无差异。两组间的比较采用χ2分析结果显示,与低SA组比较,高SA组患者具有侵袭性更强、分期更晚、危险度分层更高、更易贫血的特点,并且具有更高的LDH和ki-67水平,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05) (表2)。

3.4. 淋巴瘤患者预后危险因素分析

单因素分析:将可能影响淋巴瘤患者预后生存的各因素如血清SA水平、性别、年龄、淋巴瘤分期、Hb水平、ki67、LDH、是否HL、淋巴瘤恶性程度、疾病危险度分层等进行单因素分析,分析结果显示SA > 605 mg/L、年龄 > 60岁、贫血、LDH > 250 U/L、ki67 > 45%、高危危险度分层的淋巴瘤患者PFS显著缩短(P < 0.05),SA > 605 mg/L、年龄 > 60岁、贫血、LDH > 250 U/L、ki67 > 45%、高危危险度分层、侵袭性淋巴瘤患者OS显著缩短(P < 0.05);而在男女性别、是否是HL以及分期早晚方面PFS和OS均无明显缩短(表3)。

Table 2. Relationship between serum SA level and clinical characteristic parameters in patients with lymphoma

表2. 淋巴瘤患者血清SA水平与临床特征参数的关系

注:LDH:乳酸脱氢酶水平;HL:霍奇金淋巴瘤。

Table 3. Univariate analysis of prognosis in patients with lymphoma

表3. 淋巴瘤患者预后单因素分析

注:LDH:乳酸脱氢酶水平;HL:霍奇金淋巴瘤。

多因素分析:年龄是影响淋巴瘤患者PFS和OS的独立影响因素(P < 0.05),血清SA不是影响淋巴瘤患者PFS和OS的独立影响因素(P > 0.05) (表4)。

Table 4. Multivariate COX regression analysis of prognosis in patients with lymphoma

表4. 淋巴瘤患者预后多因素COX回归分析

注:LDH:乳酸脱氢酶水平。

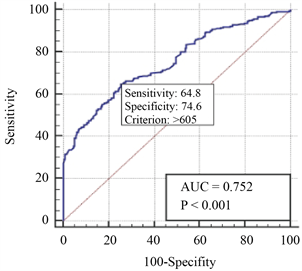

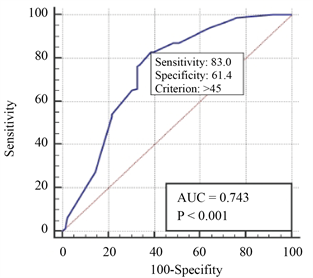

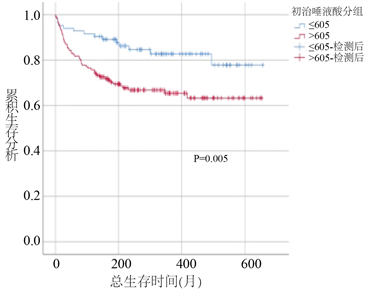

3.5. 血清SA水平对淋巴瘤患者生存的影响

采用K-M法绘制生存曲线对高、低SA组患者进行生存分析比较,经Log rank检验后发现,高SA组患者PFS和OS时间均较低SA组患者显著缩短(PFS时间:43个月对56个月,P < 0.05;OS时间:45个月对56个月;P < 0.05) (图2)。

PFS

PFS

OS

OS

Figure 2. Effect of serum SA grouping on PFS and OS of lymphoma patients

图2. 血清SA分组对淋巴瘤患者PFS、OS的影响

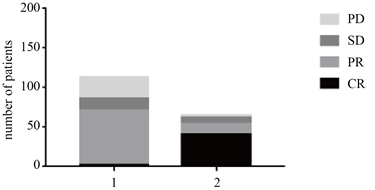

3.6. 血清SA水平对淋巴瘤患者疗效的影响

178例患者接受四个疗程规律化疗,高SA组患者获得CR、PR、SD、PD的人数分别为:2 (1.8%)、69 (61.1%)、15 (13.3%)、27 (23.9%);低SA组患者获得CR、PR、SD、PD的人数分别为:41 (63.1%)、13 (20%)、8 (12.3%)、3 (4.6%) (图3)。

注:1:高SA组,2:低SA组。

注:1:高SA组,2:低SA组。

Figure 3. Comparison of remission degree between high SA group and low SA group

图3. 高SA组、低SA组淋巴瘤患者缓解程度比较

125例淋巴瘤患者获得CR或PR,缓解后血清SA水平较治疗前显著减少,具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),未获得缓解患者的血清唾液酸水平较治疗前无明显变化(P > 0.05) (表5)。

Table 5. Changes of serum SA levels in patients with lymphoma before and after treatment

表5. 淋巴瘤患者治疗前后血清SA水平变化

高SA组患者治疗后ORR、DCR分别为62.8%、76.1%,低SA组患者治疗后ORR、DCR分别为83.1%、95.4%。高SA组淋巴瘤患者治疗ORR和DCR均低于低SA组患者,且二者之间的差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05) (表6)。

Table 6. Effect of serum SA grouping on ORR and DCR in patients with lymphoma

表6. 血清SA分组对淋巴瘤患者ORR、DCR影响

注:ORR:总缓解率;DCR:疾病控制率。

4. 讨论

肿瘤微环境是一个复杂的动态细胞环境,包含周围的免疫细胞,血管,细胞外基质,成纤维细胞,淋巴细胞,骨髓源性炎症细胞和信号分子 [10] [11],肿瘤微环境显著影响治疗反应和临床结果 [12]。因此,肿瘤免疫微环境相关研究受到越来越多的关注。

众多研究表明,唾液酸在肿瘤免疫逃逸中发挥关键作用,肿瘤细胞的唾液酸化与肿瘤侵袭性和转移力密切相关 [13] [14] [15]。肿瘤免疫假说认为免疫系统既保护宿主免受肿瘤影响,同时肿瘤本身通过肿瘤抗原诱导免疫反应而产生免疫抑制细胞因子,募集免疫调节细胞,抑制免疫系统,导致肿瘤免疫逃逸 [16]。自从糖代谢生物学和免疫学领域取得了重大进展以来,肿瘤唾液酸聚糖介导的免疫逃逸的概念也获得新的认识。唾液酸聚糖是由唾液酸残基组成的线性多糖,是糖生物学领域中重要工具,在癌细胞中过表达 [17] [18]。肿瘤细胞表面的唾液酸化糖复合物是一种有效免疫调节剂,有助于免疫微环境抑制以及肿瘤免疫逃逸 [13]。研究表明SA有利于以维持免疫系统稳定,抑制免疫系统异常激活,以避免正常细胞唾液酸化造成的损害 [17]。然而,在肿瘤微环境中,SA在癌细胞上异常高表达,与免疫细胞结合介导免疫抑制,抑制自然杀伤细胞的细胞毒性和T细胞的活化,诱导与肿瘤相关巨噬细胞的功能,从而促进肿瘤增殖及转移能力,逃避免疫系统监视 [14]。也有研究认为,SA在肿瘤细胞表面含量可以影响细胞突起和收缩,改变细胞之间粘附发生肿瘤转移 [19]。有研究表明,去除细胞唾液酸化会减弱癌症的致病性 [20],基于岩藻糖基化和唾液酸化等聚糖的评分能够比常规诊断标记物更好地诊断卵巢癌 [21]。动态监测血清SA水平变化可预测恶性肿瘤的疗效,对肿瘤负荷、疾病进展与复发、预后评估均有重要意义 [3]。

SA与大多数血清急性期反应物呈正相关 [22],在不同疾病中血清SA水平存在显著差异,在黑色素瘤和口腔癌患者血清SA水平显著升高 [6] [7],而在肝性脑病,肝硬化,肾囊肿和肝炎中显著降低 [4],在本研究中我们排除了各种可能影响血清SA水平的因素。Suzuki等人研究表明细胞表面唾液酸化是淋巴瘤侵袭性特征之一 [23] [24]。在本研究对236例淋巴瘤患者病例资料分析显示,健康组血清SA中位数为560 (502~612) mg/L,淋巴瘤组患者血清SA中位数为660 (567~786) mg/L,淋巴瘤组患者血清SA水平高于健康组,且差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。

本研究中,与低SA组比较,高SA组患者具有侵袭性更强、分期更晚、危险度分层越高、更易贫血的特点,并且具有更高的LDH和ki-67水平,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),血清SA水平与淋巴瘤不同临床特征参数,不同分期及不同危险度分层具有较好的正相关性。

经过四个疗程的标准治疗获得缓解的患者,治疗前血清SA平均值为679 mg/L,治疗后血清SA水平明显下降(P < 0.05),与之前的文献报告相符 [25] [26],唾液酸有助于监测患者病情变化;并且高SA组的总缓解率及疾病控制率显著低于低SA组,升高的血清SA水平往往可以提示淋巴瘤的分期更晚,预示着患者的预后越差。

肿瘤的发生和转移通常与细胞表面糖蛋白以及糖脂的表达有关,唾液酸化糖复合物参与细胞分化,发育,癌细胞转化。细胞唾液酸化改变伴随着唾液酸酶,唾液酸转移酶以及唾液酸相关蛋白的变化 [27],血清SA含量,唾液酸酶,唾液酸转移酶等影响唾液酸化糖复合物的合成 [27]。针对SA、唾液酸相关酶和蛋白的靶向抗体可以通过抑制SA化,抑制肿瘤进展,转移和浸润,成为治疗肿瘤转移、癌症疫苗的潜在药物 [1] [28] [29]。

综上所述,在本研究中,我们推测在血清SA > 605 mg/L时,提示淋巴瘤患者预后不佳,血清SA水平高可以提示淋巴瘤的分期更晚。动态监测血清SA水平可能有助于监测淋巴瘤病情发展变化,作为判断疾病分期以及监测治疗效果的有效指标。本研究为单中心、回顾性研究,病例数有限。我们仍需要多中心、大量样本的研究以更深入地探讨血清SA水平在淋巴瘤中的临床应用价值。

文章引用

肖晶晶,聂淑敏,李田兰,黄俊霞,毛春霞,高 燕,周静静,冯献启. 血清唾液酸水平在淋巴瘤患者中的变化及意义

Changes and Significance of Serum Sialic Acid Levels in Patients with Lymphoma[J]. 临床医学进展, 2021, 11(07): 2941-2950. https://doi.org/10.12677/ACM.2021.117426

参考文献

- 1. Schauer, R. and Kamerling, J.P. (2018) Exploration of the Sialic Acid World. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry, 75, 1-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.accb.2018.09.001

- 2. Vajaria, B.N., Patel, K.R., Begum, R., et al. (2012) Glycoprotein Electrophoretic Patterns Have Potential to Monitor Changes Associated with Neoplastic Transformation in Oral Cancer. The International Journal of Biological Markers, 27, e247-e256. https://doi.org/10.5301/JBM.2012.9147

- 3. 季海生, 厉波, 杨爱, 等. 血清唾液酸检测在恶性肿瘤诊治中的临床研究[J]. 中华全科医师杂志, 2010, 9(5): 345-346.

- 4. Huang, X., Yao, Q., Zhang, L., et al. (2019) The Serum SA Levels Are Significantly Increased in Sepsis But Decreased in Cirrhosis. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 162, 335-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.01.009

- 5. Cheeseman, J., Kuhnle, G., Spencer, D.I.R., et al. (2021) Assays for the Identification and Quantification of Sialic Acids: Challenges, Opportunities and Future Perspectives. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 30, Article ID: 115882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115882

- 6. Tsoukalas, C., Geninatti-Crich, S., Gaitanis, A., et al. (2018) Tumor Targeting via Sialic Acid: [68Ga]DOTA-en-pba as a New Tool for Molecular Imaging of Cancer with Pet. Molecular Imaging and Biology, 20, 798-807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-018-1176-0

- 7. Guruaribam, V.D. and Sarumathi, T. (2020) Relevance of Serum and Salivary Sialic Acid in Oral Cancer Diagnostics. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics, 16, 401-404. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_512_19

- 8. Rathod, S., Shori, T., Sarda, T.S., et al. (2018) Comparative Analysis of Salivary Sialic Acid Levels in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Chronic Periodontitis Patients: A Biochemical Study. Indian Journal of Dental Research, 29, 22-25. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_106_16

- 9. Cheson, B.D., Horing, S.J., Coiffier, B., et al. (1999) Report of an International Workshop to Standardize Response Criteria for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17, 1244. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244

- 10. Spill, F., Reynolds, D.S., Kamm, R.D., et al. (2016) Impact of the Physical Microenvironment on Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 40, 41-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.007

- 11. Del Prete, A., Schioppa, T., Tiberio, L., et al. (2017) Leukocyte Trafficking in Tumor Microenvironment. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 35, 40-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2017.05.004

- 12. Wang, M., Zhao, J., Zhang, L., et al. (2017) Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Tumorigenesis. Journal of Cancer, 8, 761-773. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.17648

- 13. Bull, C., Boltje, T.J., Balneger, N., Weischer, S.M., et al. (2018) Sialic Acid Blockade Suppresses Tumor Growth by Enhancing T-Cell-Mediated Tumor Immunity. Cancer Research, 78, 3574-3588. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3376

- 14. Dobie, C. and Skropeta, D. (2021) Insights into the Role of Sialylation in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. British Journal of Cancer, 124, 76-90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01126-7

- 15. Zhou, X., Yang, G. and Guan, F. (2020) Biological Functions and Analytical Strategies of Sialic Acids in Tumor. Cells, 9, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020273

- 16. Schreiber, R.D., Old, L.J. and Smyth, M.J. (2011) Cancer Immunoediting: Integrating Immunity’s Roles in Cancer Suppression and Promotion. Science, 331, 1565-1570. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203486

- 17. Bull, C., Den Brok, M.H. and Adema, G.J. (2014) Sweet Escape: Sialic Acids in Tumor Immune Evasion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1846, 238-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.07.005

- 18. Guo, X., Elkashef, S.M., Patel, A., et al. (2021) An Assay for Quantitative Analysis of Polysialic Acid Expression in Cancer Cells. Carbohydrate Polymers, 259, Article ID: 117741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117741

- 19. Sun, H.Y., Zhou, Y., Jiang, H.Y., et al. (2020) Elucidation of Functional Roles of Sialic Acids in Cancer Migration. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00401

- 20. Kohnz, R.A., Roberts, L.S., Detomaso, D., et al. (2016) Protein Sialylation Regulates a Gene Expression Signature That Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Pathogenicity. ACS Chemical Biology, 11, 2131-2139. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.6b00433

- 21. Dedova, T., Braicu, E.I., Sehouli, J., et al. (2019) Sialic Acid Linkage Analysis Refines the Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 9, 261. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00261

- 22. Nayak, S.B., Duncan, H., Lallo, S., et al. (2008) Correlation of Microalbumin and Sialic Acid with Anthropometric Variables in Type-2 Diabetic Patients with and without Nephropathy. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 4, 243-247. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.2008.04.01.243

- 23. Suzuki, O., Nozawa, Y., Kawaguchi, T., et al. (2002) UDP GlcNAc2-Epimerase Regulates Cell Surface Sialylation and Cell Adhesion to Extracellular Matrix in Burkitt’s Lymphoma. International Journal of Oncology, 20, 1005-1011. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.20.5.1005

- 24. Suzuki, O., Abe, M. and Hashimoto, Y. (2015) Sialylation and Glycosylation Modulate Cell Adhesion and Invasion to Extracellular Matrix in Human Malignant Lymphoma: Dependency on Integrin and the Rho GTPase Family. International Journal of Oncology, 47, 2091-2099. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2015.3211

- 25. Tomaszewska, R., Sonta-Jakimczyk, D., Dyduch, A., et al. (1997) Sialic Acid Concentration in Different Stages of Malignant Lymphoma and Leukemia in Children. Acta Paediatrica Japonica, 39, 448-450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.1997.tb03615.x

- 26. 张健, 张炳昌, 武春晓, 等. 血清唾液酸在三种临床常见恶性肿瘤中的检测及临床意义[J]. 医学检验与临床, 2008, 19(6): 26-28.

- 27. Vajaria, B.N., Patel, K.R., Begum, R., et al. (2016) Sialylation: An Avenue to Target Cancer Cells. Pathology & Oncology Research, 22, 443-447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-015-0033-6

- 28. Lin, C.H., Yeh, Y.C. and Yang, K.D. (2021) Functions and Therapeutic Targets of Siglec-Mediated Infections, Inflammations and Cancers. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 120, 5-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2019.10.019

- 29. Luzina, I.G., Lillehoj, E.P., Lockatell, V., et al. (2021) Therapeutic Effect of Neuraminidase-1-Selective Inhibition in Mouse Models of Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 376, 136-146. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.120.000223

NOTES

*通讯作者。