QianRen Biology

Vol.03 No.01(2016), Article ID:17137,6

pages

10.12677/QRB.2016.31001

The Role of Adipose-Derived Inflammatory Cytokines in Type 1 Diabetes

—Adipose Tissue and T1D

Lan Shao, Boya Feng, Yuying Zhang, Huanjiao Zhou, Weidong Ji, Min Wang*

The Center for Translational Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou Guangdong

Received: Feb. 23rd, 2016; accepted: Mar. 8th, 2016; published: Mar. 15th, 2016

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

ABSTRACT

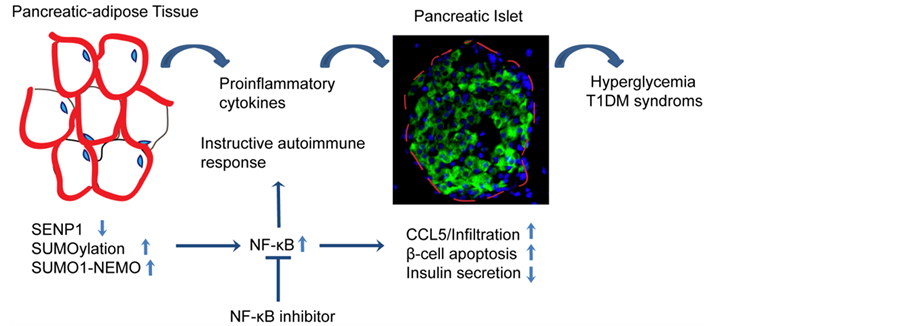

Adipocyte dysfunction correlates with the development of diabetes. Recent studies suggest that adipose tissue is not simply the organ that stores fat and regulates lipid metabolism, but also is the largest endocrine organ with immune functions. Mice with an adipocyte-specific deletion of a SUMO- specific protease SENP1 develop symptoms of type-1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) resulted from beta cell damage. Cytokine profiling indicates that peri-pancreatic adipocytes (PATs) of SENP1-dificient mice have increased proinflammatory cytokine production compared with other adipose depots. Proinflammatory cytokines originated from PATs have direct cytotoxic effects on pancreatic islets, and also increase infiltration of immune cells by augmenting CCL5 expression in adjacent pancreatic islets. Molecular analyses support that SUMOylation of NF-κB essential molecule (NEMO) in PATs leads to increased NF-κB activity, cytokine production and pancreatic inflammation. Therapeutic attempting to ameliorate the T1DM phenotype should consider using of NF-κB inhibitor against adipocyte inflammation.

Keywords:Adipocyte, Cytokine, Type 1 Diabetes, SENP1, SUMOylation, NF-κB Essential Molecule

脂肪炎症细胞因子在I型糖尿病中的作用

—脂肪组织与I型糖尿病

邵兰,冯博雅,张钰莹,周焕娇,纪卫东,王敏*

中山大学附属第一医院转化医学中心,广东 广州

收稿日期:2016年2月23日;录用日期:2016年3月8日;发布日期:2016年3月15日

摘 要

脂肪细胞的功能紊乱与糖尿病的发生有关。近来有研究表明,脂肪组织不仅仅是储存脂肪和调节脂类代谢的组织,同时也是最大的免疫功器官,脂肪细胞可通过分泌细胞因子来影响免疫功能。特异性敲除了脂肪细胞的SUMO特异蛋白酶SENP1基因的小鼠会出现I型糖尿病(type-1 diabetes mellitus, T1DM)的症状。胰腺周围脂肪组织(peri-pancreatic adipocytes, PATs)在胰腺功能中发挥了全身效应以及旁分泌作用与糖尿病的发生密切相关。胰腺周围的脂肪组织与其他脂肪储存组织相比,产生了更多的促炎细胞因子。这些促炎细胞因子对胰岛有直接的细胞毒性作用,导致邻近胰岛的炎症反应,破坏胰腺中的免疫平衡。NF-κB必要分子(NF-κB essential molecule, NEMO) SUMO化,可以增强NF-κB活性、细胞因子产生以及胰腺的炎症反应。NF-κB抑制剂为阻断炎症反应、缓解1型糖尿病提供了新的治疗策略。因此胰腺周围脂肪组织的脂肪细胞在糖尿病发生时的胰腺免疫调节建立中可能起着重要作用,为I型糖尿病的发生发展提供了可能的新的分子发病机制。

关键词 :脂肪细胞,细胞因子,I型糖尿病,SENP1,SUMO化,NF-κB必要分子

1. 引言

糖尿病在世界范围内的日益普遍,给社会和经济发展带来了沉重的负担。因此,阐明糖尿病的发病机制,是预防和控制糖尿病及其并发症的关键。糖尿病主要分为1型和2型两种类型,具有不同的致病机理。I型糖尿病由胰岛细胞的自身免疫被破坏所引起,由于胰腺中产生胰岛的胰岛细胞发生损伤,引起胰岛素的绝对不足,从而导致胰岛细胞的自身免疫遭受破坏 [1] 。II型糖尿病(type-2 diabetes mellitus, T2DM)则是在胰岛素抵抗和胰岛素相对不足的情况下,以高血糖症为特征的一种新陈代谢紊乱 [2] 。现有研究发现,炎症反应介导了糖尿病及其并发症的发生发展 [3] 。肥胖时,脂肪细胞中炎症细胞因子以及其他介质的释放,导致炎症反应,与糖尿病发生发展密切相关 [4] [5] 。然而,目前大部分的研究都聚焦在脂肪细胞的功能与II型糖尿病的发生发展关系上,对脂肪细胞炎症在I型糖尿病中是否发挥了作用仍然不清楚。

2. 脂肪细胞在I型糖尿病中的作用

有关脂肪组织在葡萄糖代谢、脂肪代谢障碍以及胰岛素耐受性方面的作用已经众所周知 [4] [6] 。近来有研究表明,脂肪组织不仅仅是储存脂肪和调节脂类代谢的组织,同时也是最大的具有免疫功能的内分泌器官 [7] 。脂肪细胞可产生多种介质,诸如脂联素、抵抗素、瘦素、单核细胞趋化蛋白-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1, MCP-1 or CCL2)以及与炎症密切相关的细胞因子,如肿瘤坏死因子-α (necrosis factor alpha, TNF-α)、白细胞介素-6 (interleukins-6, IL-6)以及白细胞介素-1β (interleukins-1beta, IL-1β)等 [8] 。此外,具有“免疫学”作用的脂肪细胞产物还包括补体系统产物和巨噬细胞集落刺激因子 [7] 。脂肪细胞中细胞因子的分泌似乎与其他细胞中的相似,细胞因子似乎是脂肪组织代谢最主要的调节因子。

越来越多证据显示,不同部位的脂肪组织,起源于不同的前体细胞,并且功能也各异 [9] [10] 。胰腺周围的脂肪组织(peri-pancreatic adipocyte tissue, PAT),传统意义上被分类为白色脂肪组织(white adipose tissue, WAT)。然而现在发现,PAT更具炎症特性,且高表达棕色脂肪标记物,如UCP-1,因此被认为更加有害且与糖尿病密切相关 [11] - [13] 。PAT中的脂肪细胞在胰腺功能和胰岛素敏感度方面发挥着全身性的和局部(旁分泌)的作用。最新研究发现,与其他局部脂肪组织来源的脂肪细胞相比,PAT脂肪细胞中的SENP1缺失,会降低脂肪细胞分化程度,显著提高促炎细胞因子表达水平,并进一步导致胰腺中免疫细胞的激活,从而导致糖尿病表型出现 [14] ,这和脂肪细胞低分化与细胞因子的产生相关的报道一致 [15] 。此外,对PAT脂肪细胞SENP1缺失小鼠进行高脂饮食喂养会进一步加重糖尿病表型。因此,鉴于其独特的功能及生化特性,PAT中的脂肪细胞也许在糖尿病中胰腺的免疫应答的建立方面发挥着主要的作用;糖尿病早期,PAT中促炎细胞因子的过度产生是免疫耐受性被破坏以及免疫细胞扩增的主要原因。该研究还证实,脂肪细胞特异性缺失SENP-1的小鼠确实自发地发生了糖尿病。这些小鼠的胰腺自身抗原特异性CD8+T细胞增高,胰岛素自身抗体(insulin autoantibody, IAA)、C反应蛋白(CRP)和β-羟基丁酸也明显增高,后三者是辅助诊断I型糖尿病的重要指标 [16] - [18] 。最新的研究结果提示,SENP-1缺失的脂肪细胞获得了类似免疫细胞的复杂功能,在将来需要对其进行进一步深入研究。

3. 脂肪细胞分泌的促炎细胞因子在I型糖尿病中的作用

PATs来源的促炎细胞因子是怎样破坏胰腺的免疫平衡的呢?首先,促炎细胞因子对胰岛免疫原性以及胰岛β-细胞的存活有直接的作用,且自身抗原存在于促炎的环境中。最新研究发现,SENP1缺失小鼠脂肪细胞的培养基上清可以强烈诱导β-细胞的凋亡和胰腺的破坏。此外,SENP1缺失小鼠模型中确实观察到大量β-细胞的凋亡,并伴随着CD8+和CD4+T细胞的浸润,说明这些小鼠发生了自身免疫的I型糖尿病。此外,在SENP1缺失的小鼠的胰腺淋巴结以及脾脏中检测到了NPR-v7自身抗原阳性的CD8+T细胞 [14] 。此前在其他糖尿病模型中的研究发现,小鼠的胰腺淋巴结中检测到了死的β-细胞,而从这些淋巴结中分离出的树突细胞可以刺激T细胞抗原受体(TCR)转基因的致糖尿病的T-细胞,从而提示了β-细胞死亡在启动T-细胞自身活化中所发挥的作用 [19] 。在疾病的发展过程中,促炎细胞因子诱导β-细胞的损伤和死亡,同时还可能会暴露新的抗原表位,从而增加致病性自身免疫细胞的特异性 [20] 。其次,胰岛中的趋化因子在促炎刺激下可能会被诱导产生。有报道称,趋化因子CCL5与趋化因子受体CCR1/3/5的结合也许有助于I型糖尿病的发生发展,在NOD小鼠的脾脏和胰岛淋巴结中也检测到了趋化因子CCL5受体(CCR5) [21] 。脂肪细胞中的促炎细胞因子可以显著地上调胰岛CCL5的表达。高浓度的PAT来源的细胞因子可以直接诱导邻近胰岛中CCL5以及其他趋化因子(如CCL2、CCL21、CXCL9和CXCL10)的表达,而趋化因子负责招募免疫细胞 [14] 。此外,在SENP1敲除的小鼠的胰腺淋巴结中,活化的树突状细胞、T细胞以及B细胞数量在糖尿病发生时的确有所增加,因此有必要进一步研究趋化因子CCL5以及其他趋化因子是否以及如何促进了I型糖尿病的进程。再次,促炎细胞因子对不同类型的免疫细胞均有直接影响,尤其是T细胞。这些免疫细胞进一步释放更多的内源性的炎性细胞因子,从而进一步损伤β-细胞,并通过活化适应性反应而破坏耐受性。有报道称,多种细胞因子可以直接作用于调节性T细胞,影响它们的分化、稳定性以及功能。在小鼠中,持续的炎症会导致Foxp3的不稳定、抑制作用的减弱以及获得产生IFN-γ的Th1细胞的功能。IL-6和IL-1β一起也可以引起胰岛自身抗原特异的调节T细胞抑制功能丧失并成为炎症Th17细胞 [22] 。在SENP1缺失小鼠的胰腺中,也出现Th1和Th17效应T细胞亚群的扩增,和调节性T细胞的数量在促炎细胞因子环境下有所减少的现象,这与其它1型糖尿病观察的结果相类似,表明在SENP1敲除小鼠的胰腺中,由于调节失败,局部免疫调节出现缺陷。总之,多项研究结果证实了脂肪组织分泌的促炎细胞因子和I型糖尿病密切相关,因此,进一步观察阻断促炎细胞因子或者细胞毒性T细胞是否可以阻止I型糖尿病的发生发展具有十分重要的作用。

4. 蛋白SUMO化调节脂肪细胞促炎细胞因子的分泌

SUMO化是由激酶、缀合酶以及连接酶介导的一个动态过程,且易在去SUMO化蛋白酶SENPs家族作用下发生可逆反应 [23] [24] 。SUMO化作为一种翻译后修饰参与了各种细胞过程,小分子泛素化修饰体(small ubiquitin-like modifier, SUMO)对蛋白的SUMO化是动态调节蛋白功能的重要机制。SUMO化与包括阿尔兹海默病(Alzheimer’s disease, AD)、亨廷顿舞蹈症(Huntington’s disease, HD)以及I型糖尿病等在内的各种疾病相关 [25] 。有趣的是,SUMO化过程中的好几个重要组分被发现是I型糖尿病易感的候选基因 [26] [27] 。位于染色体6q25上IDDM5间隔的SUMO4,研究发现了其作为I型糖尿病易感基因的有力的遗传和功能方面的证据 [28] 。细胞因子和其他参与宿主免疫应答的靶基因的表达由NF-κB家族的转录调控因子所调控 [29] 。有报道称,NF-κB的几个组分被SUMO化调节 [30] 。SUMO1和SUMO4可以将IkBa修饰,从而抵抗蛋白酶体介导的泛素化,因而抑制NF-κB的活性 [25] 。已有证据表明,在HEK 293T过表达系统,只有SENP1和SENP2,而非其他SENPs,可以有效地将NF-κB必要分子(NF-κB essential molecule, NEMO)去SUMO化,从而增强由DNA损伤诱导的NF-κB的活化 [31] [32] 。在小鼠的脂肪组织中,SENP1的表达比SENP2高出六倍。脂肪细胞中SENP1的缺失会增强NF-κB必要分子NEMO位于277和309位赖氨酸的SUMO化,从而导致NF-κB活性、细胞因子产生及胰腺炎症。虽然至今还未鉴定出SENP1的基因突变,但研究结果已提示脂肪组织中SENP1表达的降低和NF-κB活性的增强是I型糖尿病的一个重要发病机制 [14] 。此外,在患糖尿病NOD小鼠的胰腺周围脂肪组织中,SENP1的表达随着年龄的增长而降低,这与这些小鼠糖尿病的进程相一致,为进一步的临床研究奠定了基础 [14] 。

5. NF-κB抑制剂可用于治疗I型糖尿病

通过NF-κB通路介导,脂肪细胞中炎症细胞因子以及其他介质的释放与糖尿病密切相关。重要的是,在体内用NF-Kbp65核转位抑制剂JSH-23处理可以降低细胞因子的水平并改善I型糖尿病的表型 [14] 。值得注意的是,I型糖尿病和II型糖尿病具有系统相关性。最新发现SENP1缺失的小鼠有非常强的I型

SENP1使脂肪组织中的NF-κB和炎症反应保持静止。脂肪细胞特异性地缺失SENP1可以引起脂肪组织中NEMO的SUMO化、NF-κB的活化以及NF-κB依赖的促炎细胞因子的产生,尤其是在胰腺周围的脂肪组织(PAT)中。这些细胞因子会引起邻近胰岛中CCL5的高水平表达,从而招募CCR5+细胞。随后,细胞因子和活化的免疫细胞将攻击胰腺,特别是CD8+和CD4+,导致SNP1缺陷小鼠中胰岛结构的慢性破坏、β细胞的损伤、自身抗体的发作以及糖尿病的发展。因此,NF-κB的抑制剂可以阻止SENP1缺失小鼠中的炎症反应并能改善其糖尿病的进程。最新的研究表明,胰腺周围脂肪组织中SENP1表达的降低和NF-κB活性的增强也许代表着蛋白的SUMO化在I型糖尿病发病机理中发挥作用的一个普遍机制。

SENP1使脂肪组织中的NF-κB和炎症反应保持静止。脂肪细胞特异性地缺失SENP1可以引起脂肪组织中NEMO的SUMO化、NF-κB的活化以及NF-κB依赖的促炎细胞因子的产生,尤其是在胰腺周围的脂肪组织(PAT)中。这些细胞因子会引起邻近胰岛中CCL5的高水平表达,从而招募CCR5+细胞。随后,细胞因子和活化的免疫细胞将攻击胰腺,特别是CD8+和CD4+,导致SNP1缺陷小鼠中胰岛结构的慢性破坏、β细胞的损伤、自身抗体的发作以及糖尿病的发展。因此,NF-κB的抑制剂可以阻止SENP1缺失小鼠中的炎症反应并能改善其糖尿病的进程。最新的研究表明,胰腺周围脂肪组织中SENP1表达的降低和NF-κB活性的增强也许代表着蛋白的SUMO化在I型糖尿病发病机理中发挥作用的一个普遍机制。

Figure 1.A model for the role of SENP1 in T1DM

图1. SENP1在I型糖尿病中作用的模型

糖尿病表型,同时也伴随有轻微的II型糖尿病表型,会因高脂膳食加重。特别是,在SENP1缺失的小鼠中,高脂膳食会加重胰腺周围脂肪组织的形态变化、细胞因子的产生以及胰腺的损伤 [14] 。因此,亟待进一步研究高脂膳食是否改变米色脂肪细胞前体细胞表型,以及这种改变是否在肥胖糖尿病小鼠中起着关键作用。如果是这样,就可以通过NF-κB或者NEMO的抑制剂控制米色前体的炎症,从而预防肥胖患者进一步发展成糖尿病。

总的来说,最新研究进展明确了SENP1介导的蛋白SUMO化在胰腺的免疫应答、β-细胞的损伤以及糖尿病发生发展中的重要作用(见图1),为使用NEMO抑制肽段或NF-κB抑制剂治疗1型糖尿病奠定基础。胰腺脂肪细胞的免疫功能以及PAT脂肪细胞独特的分化模式方面有待更多研究。阐明胰腺脂肪细胞中SENP1介导的 SUMO化的新机制,有助于更深入认识I型糖尿病发病机制,从而更有效地防治糖尿病。

基金项目

国家自然科学基金委项目(No. 91539110)。

文章引用

邵 兰,冯博雅,张钰莹,周焕娇,纪卫东,王 敏. 脂肪炎症细胞因子在I型糖尿病中的作用—脂肪组织与I型糖尿病

The Role of Adipose-Derived Inflammatory Cytokines in Type 1 Diabetes—Adipose Tissue and T1D[J]. 千人·生物, 2016, 03(01): 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/QRB.2016.31001

参考文献 (References)

- 1. Lehuen, A., Diana, J., Zaccone, P. and Cooke, A. (2010) Immune Cell Crosstalk in Type 1 Diabetes, Nature Reviews. Immunology, 10, 501-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri2787

- 2. American Diabetes Association (2011) Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care, 34, S62-S69. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc11-S062

- 3. Navarro-Gonzalez, J.F. and Mora-Fernandez, C. (2008) The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in Diabetic Nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 19, 433-442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007091048

- 4. Tilg, H. and Moschen, A.R. (2006) Adipocytokines: Mediators Linking Adipose Tissue, Inflammation and Immunity, Nature Reviews. Immunology, 6, 772-783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri1937

- 5. Greenberg, A.S. and Obin, M.S. (2006) Obesity and the Role of Adipose Tissue in Inflammation and Metabolism. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83, 461S-465S.

- 6. Odegaard, J.I. and Chawla, A. (2012) Connecting Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes through Innate Immunity. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2, Article ID: a007724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007724

- 7. Rocha, V.Z. and Folco, E.J. (2011) Inflammatory Concepts of Obesity. International Journal of Inflammation, 2011, Article ID: 529061. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/529061

- 8. Chandran, M., Phillips, S.A., Ciaraldi, T. and Henry, R.R. (2003) Adiponectin: More Than Just Another Fat Cell Hormone? Diabetes Care, 26, 2442-2450. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.8.2442

- 9. Gesta, S., Bluher, M., Yamamoto, Y., Norris, A.W., Berndt, J., Kralisch, S., Boucher, J., Lewis, C. and Kahn, C.R. (2006) Evidence for a Role of Developmental Genes in the Origin of Obesity and Body Fat Distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103, 6676-6681. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601752103

- 10. Tchkonia, T., Lenburg, M., Thomou, T., Giorgadze, N., Frampton, G., Pirtskhalava, T., Cartwright, A., Cartwright, M., Flanagan, J., Karagiannides, I., Gerry, N., Forse, R.A., Tchoukalova, Y., Jensen, M.D., Pothoulakis, C. and Kirkland, J.L. (2007) Identification of Depot-Specific Human Fat Cell Progenitors through Distinct Expression Profiles and Developmental Gene Patterns. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 292, E298-E307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00202.2006

- 11. Franco-Pons, N., Gea-Sorli, S. and Closa, D. (2010) Release of Inflammatory Mediators by Adipose Tissue during Acute Pancreatitis. The Journal of Pathology, 221, 175-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.2691

- 12. Heni, M., Machann, J., Staiger, H., Schwenzer, N.F., Peter, A., Schick, F., Claussen, C.D., Stefan, N., Haring, H.U. and Fritsche, A. (2010) Pancreatic Fat Is Negatively Associated with Insulin Secretion in Individuals with Impaired Fasting Glucose and/or Impaired Glucose Tolerance: A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Study. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 26, 200-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.1073

- 13. Rippe, C., Berger, K., Mei, J., Lowe, M.E. and Erlanson-Albertsson, C. (2003) Effect of Long-Term High-Fat Feeding on the Expression of Pancreatic Lipases and Adipose Tissue Uncoupling Proteins in Mice. Pancreas, 26, e36-e42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006676-200303000-00024

- 14. Shao, L., Zhou, H.J., Zhang, H., Qin, L., Hwa, J., Yun, Z., Ji, W. and Min, W. (2015) SENP1-Mediated NEMO DeSUMOylation in Adipocytes Limits Inflammatory Responses and Type-1 Diabetes Progression. Nature Communications, 6, 8917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9917

- 15. Chatterjee, T.K., Stoll, L.L., Denning, G.M., Harrelson, A., Blomkalns, A.L., Idelman, G., Rothenberg, F.G., Neltner, B., Romig-Martin, S.A., Dickson, E.W., Rudich, S. and Weintraub, N.L. (2009) Proinflammatory Phenotype of Perivascular Adipocytes: Influence of High-Fat Feeding. Circulation Research, 104, 541-549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182998

- 16. Pihoker, C., Gilliam, L.K., Hampe, C.S. and Lernmark, A. (2005) Autoantibodies in Diabetes. Diabetes, 54, S52-S61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.S52

- 17. van Belle, T.L., Coppieters, K.T. and von Herrath, M.G. (2011) Type 1 Diabetes: Etiology, Immunology, and Therapeutic Strategies. Physiological Reviews, 91, 79-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00003.2010

- 18. Hu, F.B., Meigs, J.B., Li, T.Y., Rifai, N. and Manson, J.E. (2004) Inflammatory Markers and Risk of Developing Type 2 Diabetes in Women. Diabetes, 53, 693-700. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.53.3.693

- 19. Hoglund, P., Mintern, J., Waltzinger, C., Heath, W., Benoist, C. and Mathis, D. (1999) Initiation of Autoimmune Diabetes by Developmentally Regulated Presentation of Islet Cell Antigens in the Pancreatic Lymph Nodes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 189, 331-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.189.2.331

- 20. Akirav, E., Kushner, J.A. and Herold, K.C. (2008) Beta-Cell Mass and Type 1 Diabetes: Going, Going, Gone? Diabetes, 57, 2883-2888. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db07-1817

- 21. Carvalho-Pinto, C., Garcia, M.I., Gomez, L., Ballesteros, A., Zaballos, A., Flores, J.M., Mellado, M., Rodriguez-Frade, J.M., Balomenos, D. and Martinez, A.C. (2004) Leukocyte Attraction through the CCR5 Receptor Controls Progress from Insulitis to Diabetes in Non-Obese Diabetic Mice. European Journal of Immunology, 34, 548-557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/eji.200324285

- 22. Zhang, Y., Bandala-Sanchez, E. and Harrison, L.C. (2012) Revisiting Regulatory T Cells in Type 1 Diabetes. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 19, 271-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MED.0b013e328355a2d5

- 23. Li, S.J. and Hochstrasser, M. (1999) A New Protease Re-quired for Cell-Cycle Progression in Yeast. Nature, 398, 246- 251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/18457

- 24. Gill, G. (2004) SUMO and Ubiquitin in the Nucleus: Different Functions, Similar Mechanisms? Genes & Development, 18, 2046-2059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1214604

- 25. Li, M., Guo, D., Isales, C.M., Eizirik, D.L., Atkinson, M., She, J.X. and Wang, C.Y. (2005) SUMO Wrestling with Type 1 Diabetes. Journal of Molecular Medicine, 83, 504-513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00109-005-0645-5

- 26. Guo, D., Li, M., Zhang, Y., Yang, P., Eckenrode, S., Hopkins, D., Zheng, W., Purohit, S., Podolsky, R.H., Muir, A., Wang, J., Dong, Z., Brusko, T., Atkinson, M., Pozzilli, P., Zeidler, A., Raffel, L.J., Jacob, C.O., Park, Y., Serrano-Rios, M., Larrad, M.T., Zhang, Z., Garchon, H.J., Bach, J.F., Rotter, J.I., She, J.X. and Wang, C.Y. (2004) A Functional Variant of SUMO4, a New I Kappa B Alpha Modifier, Is Associated with Type 1 Diabetes. Nature Genetics, 36, 837-841. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng1391

- 27. Aribi, M. (2008) Candidate Genes Implicated in Type 1 Diabetes Susceptibility. Current Diabetes Reviews, 4, 110- 121. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/157339908784220723

- 28. Wang, C.Y., Podolsky, R. and She, J.X. (2006) Genetic and Functional Evidence Supporting SUMO4 as a Type 1 Diabetes Susceptibility Gene. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1079, 257-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1375.039

- 29. Hayashi, T. and Faustman, D. (1999) NOD Mice Are Defective in Proteasome Production and Activation of NF-kap- paB. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 19, 8646-8659. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.19.12.8646

- 30. Mabb, A.M. and Miyamoto, S. (2007) SUMO and NF-kappaB Ties. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 64, 1979- 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00018-007-7005-2

- 31. Huang, T.T., Wuerzberger-Davis, S.M., Wu, Z.H. and Miyamoto, S. (2003) Sequential Modification of NEMO/IKK- gamma by SUMO-1 and Ubiquitin Mediates NF-kappaB Activation by Genotoxic Stress. Cell, 115, 565-576. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00895-X

- 32. Lee, M.H., Mabb, A.M., Gill, G.B., Yeh, E.T. and Miyamoto, S. (2011) NF-kappaB Induction of the SUMO Protease SENP2: A Negative Feedback Loop to Attenuate Cell Survival Response to Genotoxic Stress. Molecular Cell, 43, 180- 191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.017

*通讯作者。