Advances in Geosciences

Vol.4 No.03(2014), Article

ID:13679,6

pages

DOI:10.12677/AG.2014.43014

Research Status and Prospect of Marine Nitrous Oxide

College of the Environment and Ecology, Xiamen University, Xiamen

Email: linhua@xmu.edu.cn

Copyright © 2014 by author and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: Apr. 11th, 2014; revised: May 12th, 2014; accepted: May 21st, 2014

ABSTRACT

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas, playing a significant role in the global climate system. The world ocean is believed to be a net natural source of atmospheric N2O, among which the coastal ocean is responsible for a large part of the oceanic N2O emissions. In this paper, the present research progresses of the marine N2O dissolution, fluxes and behavior are reviewed, and in addition, new methods determining the dissolved N2O are introduced, including stable isotopes application and wavelength-scanned cavity ring-down spectrophotometer, so as to provide novel techniques for researching of ocean N2O cycle in the future.

Keywords:Nitrous Oxide, Distribution, Mechanism, Flux

海洋氧化亚氮研究现状

与展望

林 华

厦门大学环境与生态学院,厦门

Email: linhua@xmu.edu.cn

收稿日期:2014年4月11日;修回日期:2014年5月12日;录用日期:2014年5月21日

摘 要

氧化亚氮(N2O)是主要的温室气体之一,影响全球气候,对大气化学也有着重要作用。而海洋是大气中N2O的重要排放源,特别是在近岸海区,N2O的释放量尤为显著。本文概述了海洋中N2O的分布特征、产生和消耗的控制机理及海–气N2O交换通量,并展望了海水N2O的新技术方法,如稳定同位素技术和波长扫描–光腔衰荡光谱技术,以期成为今后海洋N2O的研究利器。

关键词

氧化亚氮,分布,机制,通量

1. 引言

氧化亚氮(N2O)是一种对气候和大气化学产生重要影响的痕量气体。首先,它与二氧化碳(CO2)和甲烷(CH4)并列长寿命温室气体,N2O在大气中的滞留时间约114~120年[1] ,可以通过吸收红外辐射而产生温室效应,直接影响全球气候。虽然N2O在大气中的浓度比CO2小很多,但是其单分子吸收辐射的能力是CO2的296~340倍,对温室效应的贡献占了5%~6%[2] 。其次,在平流层它能与氧原子作用形成NO自由基,从而导致臭氧层的损耗[3] [4] 。工业革命以来,由于人为活动的加剧,如农田耕地面积的扩大及化肥使用量的增加,导致N2O排放增强,全球大气N2O浓度已明显增加,目前已经远远超出了根据冰芯记录测定的工业化前几千年中的浓度值。大气中N2O平均浓度已从在工业革命之前270 ppb (10−9)左右增加到2013年的325 ppb左右,显示出其源汇的失衡。

大气N2O的来源主要包括海洋、河川、土壤、沉积物和人类工农业生产的排放。海洋是大气N2O的重要自然源,海洋向大气输送的N2O占总输送量的25%~33%[5] [6] ,其中,高生产力的近岸海域包括河口和上升流区的贡献量高达60%[7] [8] 。由于人类活动加剧,大气N2O等温室气体浓度增加导致全球变暖问题,已严重影响生态系统平衡及人类社会可持续发展,而海洋,尤其近海海域,作为大气N2O的重要源区越来越受到各国气候学家和海洋学家的高度关注。

2. 海水中N2O产生与消耗机制

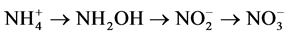

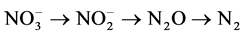

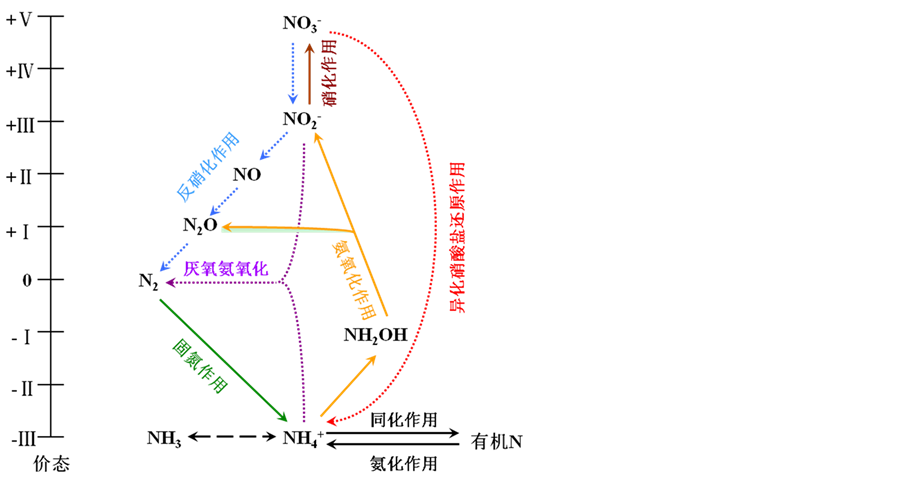

海洋N2O的产生与消耗是海洋氮循环过程的一个重要环节[9] ,其产生的主控机制亦成为当今海洋生物地球化学和气候变迁研究中的关键问题之一。由于海洋中生物化学过程的复杂性和不同海区存在的理化差异,有关N2O的产生机制至今仍然存在很多的疑问。目前,海洋中存在的可能的N2O产生与消耗机制主要有两种,硝化作用和反硝化作用(图1),其表达式如下:

硝化作用: (1)

(1)

反硝化作用: (2)

(2)

其中,硝化作用是 在有氧环境中被硝化菌氧化为

在有氧环境中被硝化菌氧化为 的过程,它由两个连续而又不同的阶段构成:首先,

的过程,它由两个连续而又不同的阶段构成:首先, 在氨氧化细菌或氨氧化古菌的媒介作用下被氧化为

在氨氧化细菌或氨氧化古菌的媒介作用下被氧化为 ,随后,

,随后, 在亚硝酸盐氧化酶的催化作用下氧化成为

在亚硝酸盐氧化酶的催化作用下氧化成为 ,其中N2O在硝化作用的前一个过程中作为副产物而产生[10] -[12] 。而当水体或沉积物中的溶解氧浓度足够低时会发生反硝化,即在

,其中N2O在硝化作用的前一个过程中作为副产物而产生[10] -[12] 。而当水体或沉积物中的溶解氧浓度足够低时会发生反硝化,即在 还原为N2的过程中,N2O作为反硝化过程的中间产物而释放[13] [14] 。反硝化过程除可以产生N2O外,在缺氧区中心或无氧海水和沉积物环境中,它还能通过使N2O进一步转化为N2而净消耗N2O[15] [16] 。

还原为N2的过程中,N2O作为反硝化过程的中间产物而释放[13] [14] 。反硝化过程除可以产生N2O外,在缺氧区中心或无氧海水和沉积物环境中,它还能通过使N2O进一步转化为N2而净消耗N2O[15] [16] 。

Figure 1. Nitrogen cycling in marine environment (modified from Gruber (2008) [9] )

图1. 海洋氮循环过程示意图(改编自Gruber(2008)[9] )

3. 海洋N2O的分布及其调控机制

由于海域环境的物理、生物、化学等条件的差异,全球海域不同水体中N2O浓度分布和控制机制存在着差异。不同海域的表层N2O分布相当不均匀,根据物理水文及生物化学影响的不同,将海域环境分成河口区、边缘海及开阔海洋等三大类,分别探讨各区域中的N2O主要分布特征及可能的调控机制。

首先,河口区是陆地、海洋与大气相互作用最为活跃、最为复杂的区域,亦是海洋向大气释放N2O的重要来源。尽管河口区域的面积仅占全球海洋的0.4%,但它们所释放的N2O却占了整个海洋的33%[7] 。研究表明,河口区水体中N2O饱和度很高,这主要是由于河口区域受人为活动影响较大,来自农田化肥的大量使用以及污水的排放向河口区域输入大量的有机氮和无机氮,且河口区域常存在着缺氧区,伴随着显著的硝化作用和反硝化作用发生[17] [18] ,从而增加水体和沉积物中N2O的产量[19] [20] 。

硝化、反硝化作用是河口区域重要的生物地球化学过程。输入河口的氮约有一半通过反硝化作用以气体的形式释放到大气中[21] ,N2O作为硝化作用的副产物和反硝化作用的中间产物,在很多河口,往往出现高度的过饱和现象[22] 。国内外研究者对于河口区域N2O分布特征及产生机制有了一定的认识,但是,由于水文环境、生物化学的差异,在不同的河口,N2O产生的主控机制存在着差异。从报道的文献看,很多河口,尤其是缺氧区存在较明显的硝化作用[23] 。例如,De Wilde等(2000)发现Schelde河口水体的硝化作用速率最高可达6400 μmol·N·L−1·h−1,并表明硝化作用是造成N2O在河口积累的主要原因[22] 。Barens等(1998)在Humber河口进行了的研究,发现河口中N2O的产生主要归因于沉积物中的反硝化作用,同时河口上游也存在非常强的硝化作用[24] ;Usui等[25] (2001)测定了Tama河口沉积物的硝化与反硝化速率分别高达246~716 μmol·N·m−2·h−1和214~1260 μmol·N·m−2·h−1,并计算了N2O释放通量达到1250 μmol·N·m−2·h−1。需要指出的是,上述研究多单一分析了河口中硝化或反硝化作用的速率,然而,河口区中水体和沉积物的硝化与反硝化作用往往耦合发生,这两者的产生N2O的速率及相对贡献尚缺乏深入的研究和评估。

边缘海等近岸海域中表层水体N2O饱和度也较高,尤其在沿岸上升流海区,水体上升流等物理过程可显著影响N2O在表层海水中的分布,下层通过生物作用产生的富含N2O的水体,可通过沿岸上升流作用涌升而被带入表层水体中,导致表层N2O高饱和度现象。例如Naqvi等(2000)在印度西海岸海区观测到表层水体N2O饱和度最高达到8000%以上[8] ;Cornejo等(2007)[26] 在智利沿岸上升流区观测到表层N2O饱和度最高可达1372%;Pierotti and Rasmussen等(1980)[27] 在秘鲁沿岸上升流区观测到表层N2O饱和度为109%~264%,而Bange等(1996)[16] 在阿曼沿岸上升流区观测到表层N2O饱和度为99%~304%,显示着近岸边缘海区也是海洋N2O一个重要释放源区。

而在开阔大洋海区,相较近岸水体,表层海水常处于寡营养水平,生物活动作用较小,表层水体的N2O主要是来自透光层底部的硝化作用以及更深层水中的硝化、反硝化过程产生并通过水体的湍流扩散作用交换到上层水体[28] ,表层N2O饱和度相对较小。Butler等(1989)[12] 于西太平洋区观测到的N2O平均饱和度为102.5%,Upstill-Goddard等(1999)[29] 在西北印度洋的非上升流的开阔大洋区观测期间表层N2O饱和度也仅为106% ± 7%。全球开阔大洋表层海水N2O的平均饱和度为103%,是大气N2O的一个弱源[5] 。

在很多开阔大洋海区,包括太平洋、大西洋和印度洋绝大多数的海域,N2O在垂直断面上的分布与DO呈现很好的镜像关系[30] [31] ,N2O浓度在上层海洋随深度增加而逐渐升高,在DO的极小值附近往往对应有N2O极大值,随着深度加深,略有降低。在2000 m水深以下,N2O浓度趋于稳定,但沿着大洋深层环流路线,从北大西洋到北大平洋,深层水N2O浓度值不断增加,这与深层水年龄变化呈现着一致关系,表明深层水N2O主要受控于硝化作用[32] 。

而在一些深层存在缺氧区域的海域,如阿拉伯海和东赤道太平洋,存在着显著的反硝化作用,N2O垂直断面分布上往往会在DO最小值区域的上层和下层分别出现两个极大值,而在缺氧的核心区域,N2O会通过反硝化作用还原为N2而出现浓度的极小值[33] 。在一些厌氧区域,如波罗的海中部、Cariaco海盆和Saanich湾区域,N2O会通过反硝化作用消耗完全,浓度接近于0,成为N2O汇区[13] [14] [34] 。

水体中N2O的产生或消耗受多种因素影响,DO、氮盐、压力、温度、盐度、pH值及浊度等皆会影响N2O浓度水平[35] ,其中DO含量被认为是生物N2O的产生或消耗主要的控制因素。在很多大洋水体中,N2O与表观耗氧量(AOU)呈现出的良好线性关系,表明N2O的产生可能来自于硝化作用[36] 。在很多大洋,N2O和DO两者有着良好的负相关关系,这一关系说明了N2O产量可能受到DO浓度的影响控制。Suntharalingam(2000)发现N2O通过硝化作用过程的产率会随着DO含量的降低而升高,结果显示水体N2O的产率在DO饱和度为1%会是在饱和度为100%状态下的20倍[37] 。因此,水体DO浓度变化影响着海洋中N2O的产生效率,并可能最终成为决定海洋在大气N2O源汇的一个因素。Codispoti(2010)指出,由于人类活动的加剧,在未来一段时间会导致海洋水体缺氧或低氧水体面积的扩大,改变海洋N2O的产生或消耗量,进而影响整个海洋N2O源汇格局[38] 。

4. 海–气N2O的交换通量

海洋的N2O源汇通量计算一直是气候学家和海洋学家们研究的焦点之一。Nevision等(1995)[5] 通过对全球各大洋超过6万个的大气和表层海水中N2O的分压差数据进行了统计分析和计算,估算出从海洋向大气释放的N2O约为4 Tg·yr−1(1.2~6.8 Tg·yr−1);Codispoti(2010)[38] 估算了大气N2O释放量在开阔大洋约为6 Tg·yr−1。随着N2O测定技术的提高和更广泛调查的展开,虽然对大洋的N2O源汇量级有了较一致的认识,但对时空变化剧烈的近岸海区仍缺乏足够的认识,还不能较好地定量其通量大小,且近岸海区的物理、生物地球化学过程远比开阔大洋复杂,如水华事件,上升流、涡旋等中尺度过程频发,使得其在源汇研究带来更大挑战,因此加强在河口和近岸海域海–气N2O通量研究对于进一步准确评估海–气N2O通量有着重要的意义。

5. 海洋N2O的分析方法及新技术的应用

海水中溶解N2O的分析,传统方法通常将水样进行前处理后得到气体,经色谱柱分离出N2O,然后使用电子俘获检测器(ECD)检测。研究者几十年的不断努力改进N2O分析方法,已将静态顶空或吹扫捕集等样品预处理技术与气相色谱技术中高灵敏度的ECD检测器联用[39] [40] ,虽并获得了一些相当高质量的海水中N2O数据,但是所能获得数据还十分有限,如何实现在现场观测中自动、快速的获得连续、高精度的N2O数据,仍将是科学家们努力的目标。

除了大量N2O浓度数据为N2O的源汇及调控机制的研究提供了证据支持外,随着质谱分析技术的发展,海洋中稳定氮、氧同位素方法也应用于这一研究。Yoshida等(1984)最早在N2O的生物地球化学循环中引进了氮同位素比值的方法[41] ,这主要是不同的生物作用和物理作用(如海–气交换)对氮、氧同位素具有不同的分馏效应,由于生物更倾向优先利用较轻的稳定同位素,硝化和反硝化作用对N2O的氮、氧同位素的亏损或富集值要高于海–气交换物理作用[42] ,因此,海洋N2O的生物作用过程会在N2O同位素值上有着清晰的信号体现。稳定同位素分析方法作为一把研究利器,已不断运用于揭示海洋N2O产生和消耗机制,区分硝化过程和反硝化不同过程对N2O的贡献,并可以根据同位素质量守恒原理来重新衡量海洋N2O源汇格局,降低海–气N2O通量估算的不确定性[43] [44] 。

近年来,波长扫描–光腔衰荡光谱技术作为一种新型的光谱检测方法,以超高灵敏度、精准度的实现N2O等温室气体浓度和同位素比值同步原位在线分析[45] ,媲美传统质谱仪,其体积小,携带方便,操作简易,快速分析的特性让野外及大面积海洋N2O走航观测的需求得以实现。这一光谱技术在未来将成为应用趋势,用于在线获得海洋高时空分辨率的溶解N2O浓度及其同位素数据,以降低海洋N2O气体收支估算的不确定性,并厘清其源汇的控制机制与循环过程。

6. 展望

准确定量海–气N2O通量并掌握其在不同时空尺度变化过程及其调控机制是当前科学家们迫切解决的两大问题,准确定量高时空变异的区域(如近岸海域,河口和滨海湿地等)水–气N2O气体通量极度受限于缺乏现场快速连续观测技术的发展,基于波长扫描–光腔衰荡光谱技术为实现船载获得高时空分辨率的N2O气体浓度和同位素数据,同步解决其来源、变化过程及其控制机制提供了可能;同时基于质谱分析技术发展的稳定同位素方法,也为我们更清晰地了解N2O产生和消耗机制提供了一个有力的手段。

参考文献 (References)

- [1] Solomon, S., Qin, D., Manning, M., Chen, Z., Marquis, M., Averyt, K.B., Tignor, M. and Miller, H.L. (2007) Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- [2] Albritton, D., Derwent, R., Isaksen, I. and Wuebbles, L.M. (1996) Radiative forcing of climate change. In: Houghton, J.T., et al., Eds., Climate Change 1995: The Science of Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, New York, 118- 131.

- [3] Crutzen, P.J. (1970) The influence of nitrogen oxides on the atmospheric ozone content (NO and nitrogen dioxide influence on ozone concentration and production rate in stratosphere). Royal Meteorological Society, Quarterly Journal, 96, 320-325.

- [4] Khalil, M.A.K. and Rasmussen, R.A. (1992) The global sources of nitrous oxide. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 14651-14660.

- [5] Nevison, C.D., Weiss, R.F. and Erickson Iii, D.J. (1995) Global oceanic emissions of nitrous oxide. Journal of Geophysical Research, 100, 15809-15820.

- [6] Seitzinger, S.P., Kroeze, C. and Styles, R.V. (2000) Global distribution of N2O emissions from aquatic systems: Natural emissions and anthropogenic effects. Chemosphere-Global Change Science, 2, 267-279.

- [7] Bange, H.W., Rapsomanikis, S. and Andreae, M.O. (1996) Nitrous oxide in coastal waters. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 10, 197-207.

- [8] Naqvi, S.W.A., Jayakumar, D.A., Narvekar, P.V., Naik, H., Sarma, V.V.S.S., D’Suza, W., Joseph, S. and George, M.D. (2000) Increased marine production of N2O due to intensifying anoxia on the Indian continental shelf. Nature, 408, 346-349.

- [9] Gruber, N. (2008) Nitrogen in the marine environment. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, San Diego, 1-51.

- [10] Codispoti, L.A. and Christensen, J.P. (1985) Nitrification, denitrification and nitrous oxide cycling in the eastern tropical South Pacific Ocean. Marine Chemistry, 16, 277-300.

- [11] Kim, K. and Craig, H. (1990) Two-isotope characterization of N2O in the Pacific Ocean and constraints on its origin in deep water. Nature, 347, 58-61.

- [12] Butler, J.H., Elkins, J.W. and Thompson, T.M. (1989) Tropospheric and dissolved N2O of the West Pacific and East Indian Oceans during the EI Nino southern oscillation event of 1987. Journal of Geophysical Research, 94, 14865- 14877.

- [13] Cohen, Y. (1978) Consumption of dissolved nitrous oxide in an anoxic basin, Saanich inlet, British-Columbia. Nature, 272, 235-237.

- [14] Walter, S., Breitenbach, U., Bange, H.W., Nausch, G. and Wallace, D.W.R. (2006) Distribution of N2O in the Baltic Sea during transition from anoxic to oxic conditions. Biogeosciences, 3, 557-570.

- [15] Elkins, J.W., Wofsy, S.C., McElroy, M.B., Kaplan, W.A. and Kolb, C.E. (1978) Aquatic sources and sinks for nitrous oxide. Nature, 275, 602-606.

- [16] Bange, H.W., Rapsomanikis, S. and Andreae, M.O. (1996) Nitrous oxide emissions from the Arabian Sea. Geophysical Research Letters, 23, 3175-3178.

- [17] de Bie, M.J.M., Middelburg, J.J., Starink, M. and Laanbroek, H.J. (2002) Factors controlling nitrous oxide at the microbial community and estuarine scale. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 240, 1-9.

- [18] Dai, M., Wang, L., Guo, X., Zhai, W., Li, Q., He, B. and Kao, S.J. (2008) Nitrification and inorganic nitrogen distribution in a large perturbed river/estuarine system: The Pearl River Estuary, China. Biogeosciences, 5, 1227-1244.

- [19] Seitzinger, S.P., Pilson, M.E.Q. and Nixon, S.W. (1983) Nitrous oxide production in nearshore marine sediments. Science, 222, 1244-1246.

- [20] Hemond, H.F. and Duran, A.P. (1989) Fluxes of N2O at the sediment-water and water-atmosphere boundaries of a nitrogen-rich river. Water Resources Research, 25, 839-846.

- [21] Howarth, R.W., Billen, G., Swaney, D., Townsend, A., Jaworski, N., Lajtha, K., Downing, J.A., Elmgren, R., Caraco, N. and Jordan, T. (1996) Regional nitrogen budgets and riverine N & P fluxes for the drainages to the North Atlantic Ocean: Natural and human influences. Biogeochemistry, 35, 75-139.

- [22] De Wilde, H.P.J. and De Bie, M.J.M. (2000) Nitrous oxide in the Schelde Estuary: Production by nitrification and emission to the atmosphere. Marine Chemistry, 69, 203-216.

- [23] de Bie, M.J.M., Starink, M., Boschker, H.T.S., Peene, J.J. and Laanbroek, H.J. (2002) Nitrification in the Schelde Estuary: Methodological aspects and factors influencing its activity. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 42, 99-107.

- [24] Barnes, J. and Owens, N.J.P. (1998) Denitrification and nitrous oxide concentrations in the Humber Estuary, UK, and adjacent coastal zones. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37, 247-260.

- [25] Usui, T., Koike, I. and Ogura, N. (2001) N2O production, nitrification and denitrification in an estuarine sediment. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 52, 769-781.

- [26] Cornejo, M., Farias, L. and Gallegos, M. (2007) Seasonal cycle of N2O vertical distribution and air-sea fluxes over the continental shelf waters off central Chile (~36˚S). Progress in Oceanography, 75, 383.

- [27] Pierotti, D. and Rasmussen, R.A. (1980) Nitrous oxide measurements in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Tellus, 32, 56-72.

- [28] Ronner, U. (1983) Distribution, production and consumption of nitrous oxide in the Baltic Sea. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 47, 2179-2188.

- [29] Upstill-Goddard, R.C., Barnes, J. and Owens, N.J.P. (1999) Nitrous oxide and methane during the 1994 SW monsoon in the Arabian Sea/northwestern Indian Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans, 104, 30067-30084.

- [30] Oudot, C., Jean-Baptiste, P., Fourre, E., Mormiche, C., Guevel, M., Ternon, J.F. and Le Corre, P. (2002) Transatlantic equatorial distribution of nitrous oxide and methane. Deep-Sea Research Part I—Oceanographic Research Papers, 49, 1175-1193.

- [31] Walter, S., Bange, H.W., Breitenbach, U. and Wallace, D.W.R. (2006) Nitrous oxide in the North Atlantic Ocean. Biogeosciences, 3, 607-619.

- [32] Bange, H.W. and Andreae, M.O. (1999) Nitrous oxide in the deep waters of the world’s oceans. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 13, 1127-1135.

- [33] Bange, H.W., Rapsomanikis, S. and Andreae, M.O. (2001) Nitrous oxide emissions from the Arabian Sea: A synthesis. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 1, 61-71.

- [34] Hashimoto, L.K., Kaplan, W.A., Wofsy, S.C. and McElroy, M.B. (1983) Transformations of fixed nitrogen and N2O in the Cariaco Trench. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, 30, 575-590.

- [35] Abril, G., Riou, S.A., Etcheber, H., Frankignoulle, M., de Wit, R. and Middelburg, J.J. (2000) Transient, tidal timescale, nitrogen transformations in an estuarine turbidity maximum-fluid mud system (The Gironde, South-West France). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 50, 703-715.

- [36] Bange, H.W. (2008) Nitrogen in the marine environment. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, San Diego, 51-94.

- [37] Suntharalingam, P., Sarmiento, J.L. and Toggweiler, J.R. (2000) Global significance of nitrous oxide production and transport from oceanic low-oxygen zones: A modeling study. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 14, 1353-1370.

- [38] Codispoti, L.A. (2010) Interesting times for marine N2O. Science, 327, 1339-1340.

- [39] Butler, J.H. and Elkins, J.W. (1991) An automated technique for the measurement of dissolved N2O in natural waters. Marine Chemistry, 34, 47-61.

- [40] Punshon, S. and Moore, R.M. (2004) Nitrous oxide production and consumption in a eutrophic coastal embayment. Marine Chemistry, 91, 37-51.

- [41] Yoshida, N., Hattori, A., Saino, T., Matsuo, S. and Wada, E. (1984) 15N/14N ratio of dissolved N2O in the eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Nature, 307, 442-444.

- [42] Yamagishi, H., Westley, M.B., Popp, B.N., Toyoda, S., Yoshida, N., Watanabe, S., Koba, K. and Yamanaka, Y. (2007) Role of nitrification and denitrification on the nitrous oxide cycle in the eastern tropical North Pacific and Gulf of California. Journal of Geophysical Research, 112.

- [43] Toyoda, S., Yoshida, N., Miwa, T., Matsui, Y., Yamagishi, H., Tsunogai, U., Nojiri, Y. and Tsurushima, N. (2002) Production mechanism and global budget of N2O inferred from its isotopomers in the western North Pacific. Geophysical Research Letters, 29.

- [44] Popp, B.N., Westley, M.B., Toyoda, S., Miwa, T., Dore, J.E., Yoshida, N., Rust, T.M., Sansone, F.J., Russ, M.E., Ostrom, N.E. and Ostrom, P.H. (2002) Nitrogen and oxygen isotopomeric constraints on the origins and sea-to-air flux of N2O in the oligotrophic subtropical North Pacific gyre. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 16.

- [45] Balslev-Clausen, D., Farinas, A., Buizert, C., Crosson, E. and Blunier, T. (2010) Continuous in field measurements of N2O concentration and its isotopologue and isotopomer ratios, with a field deployed mid-infrared, wavelength scanned, cavity ring-down spectroscopy instrument. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, 12, 6974.