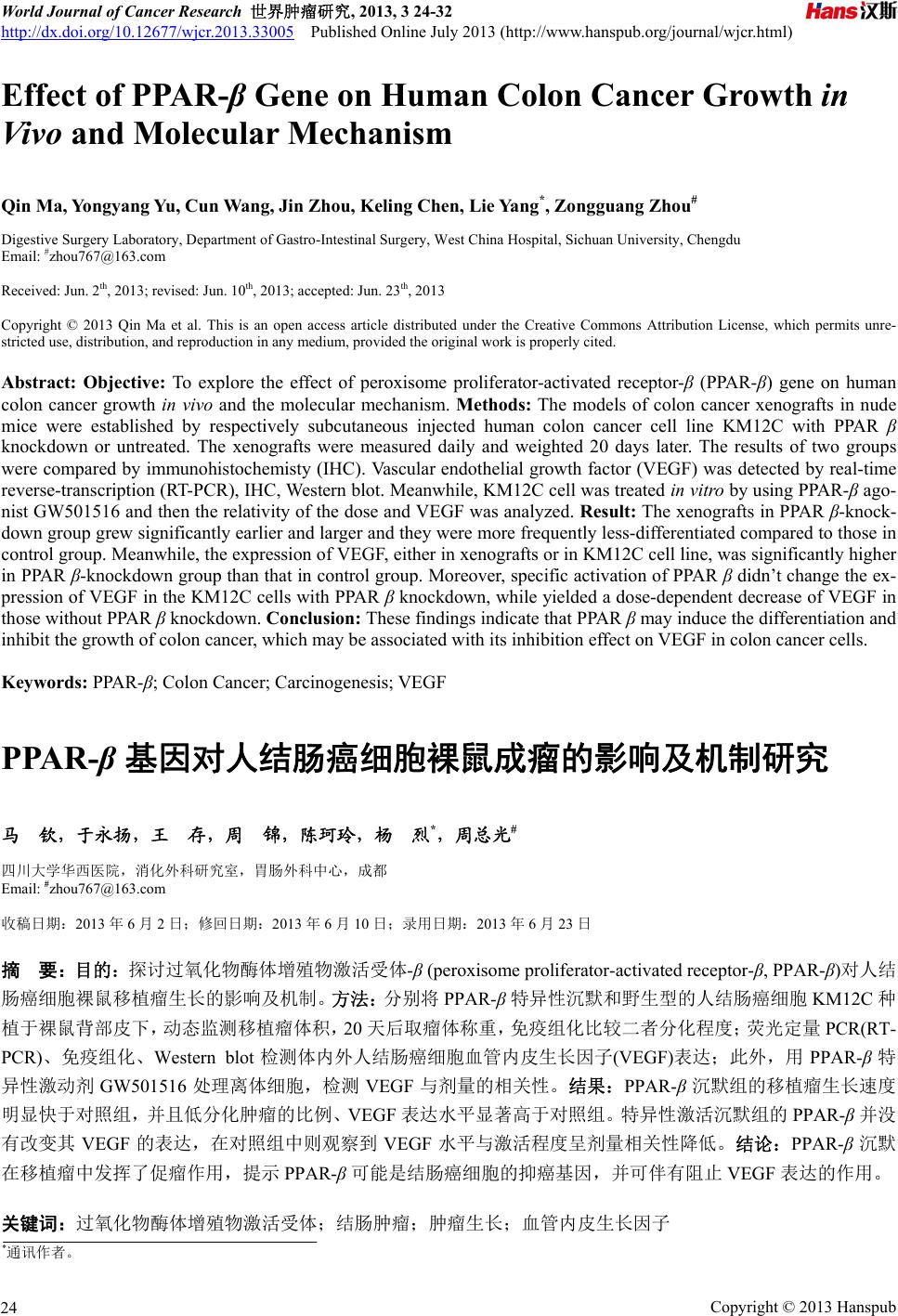

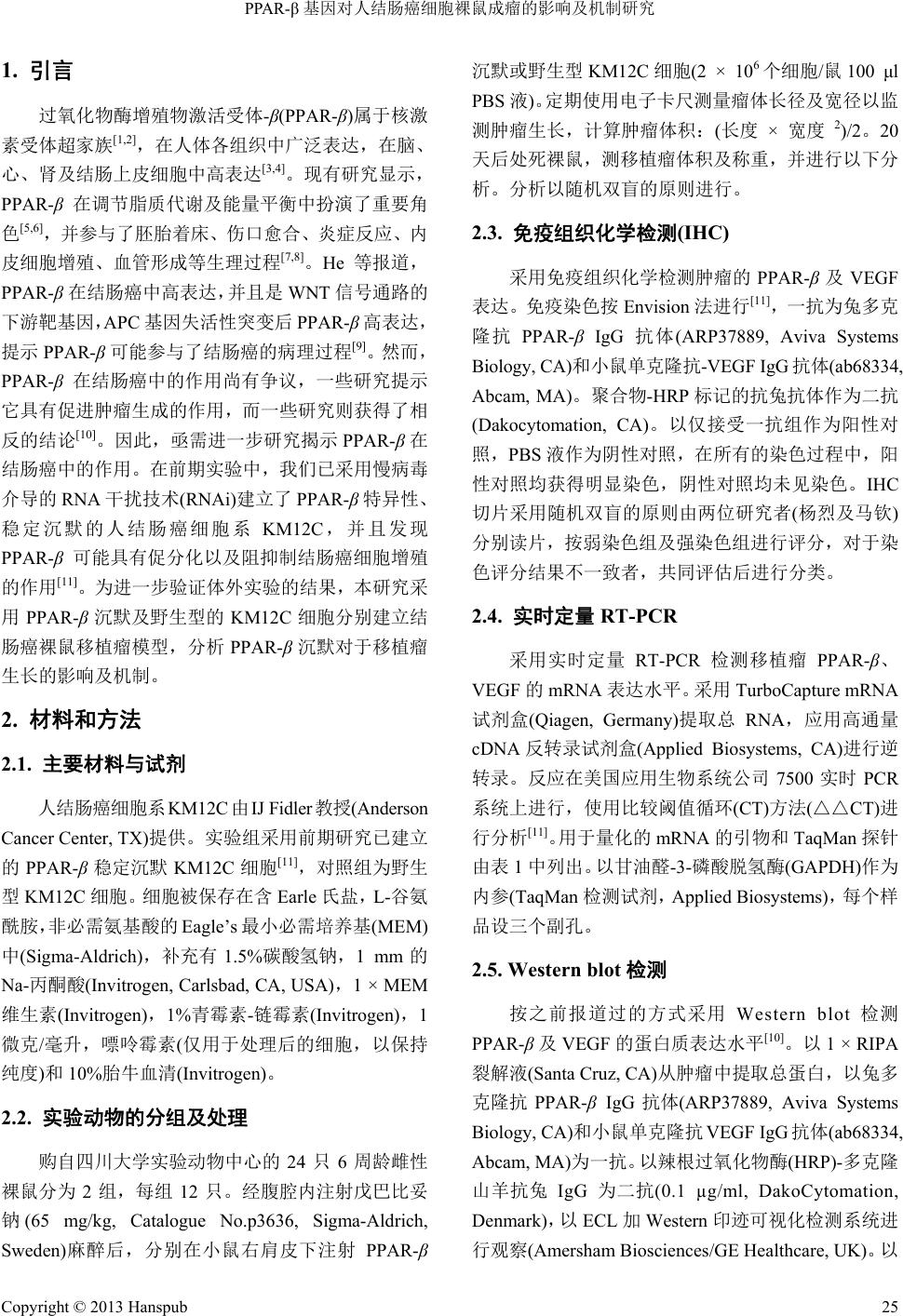

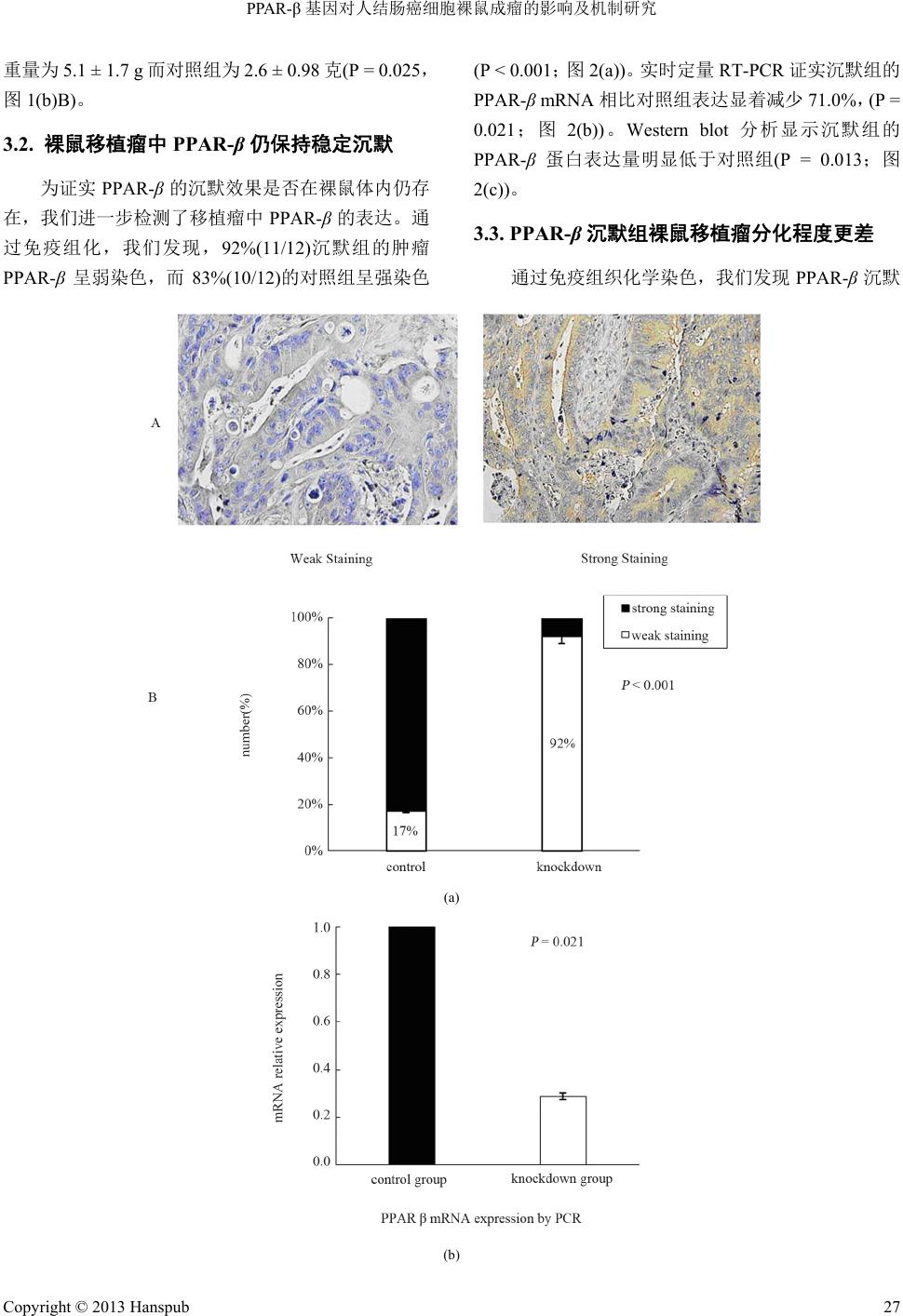

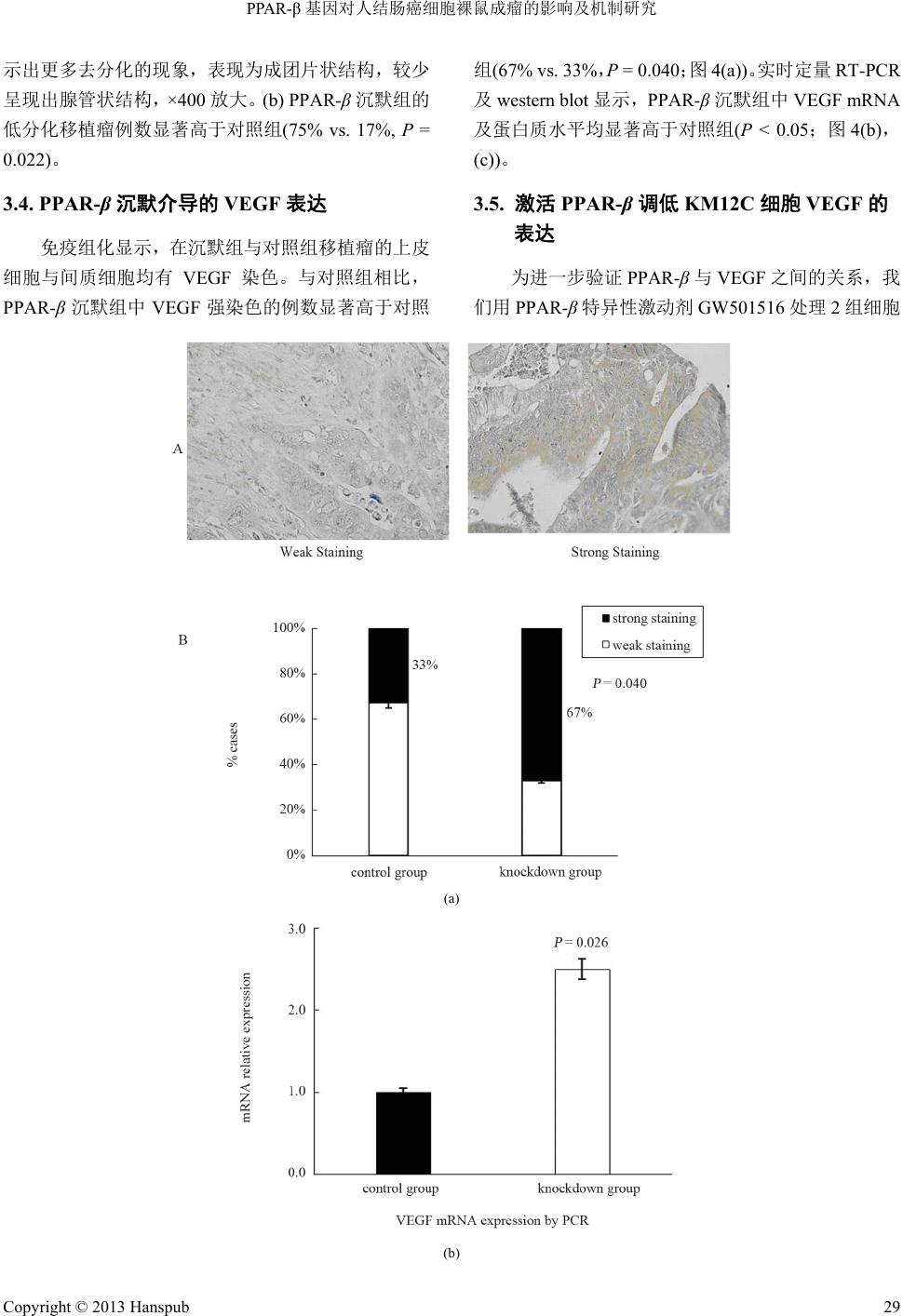

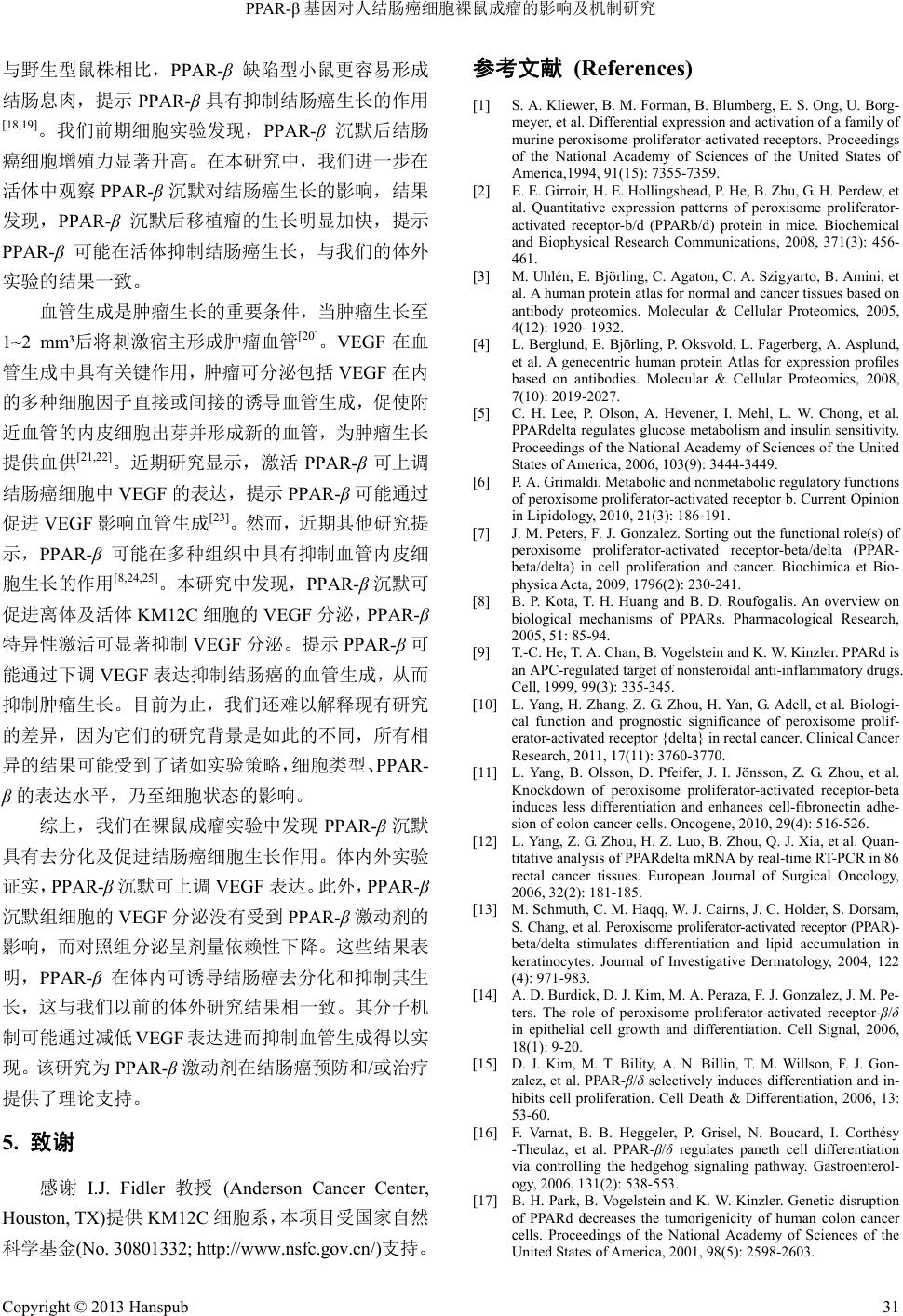

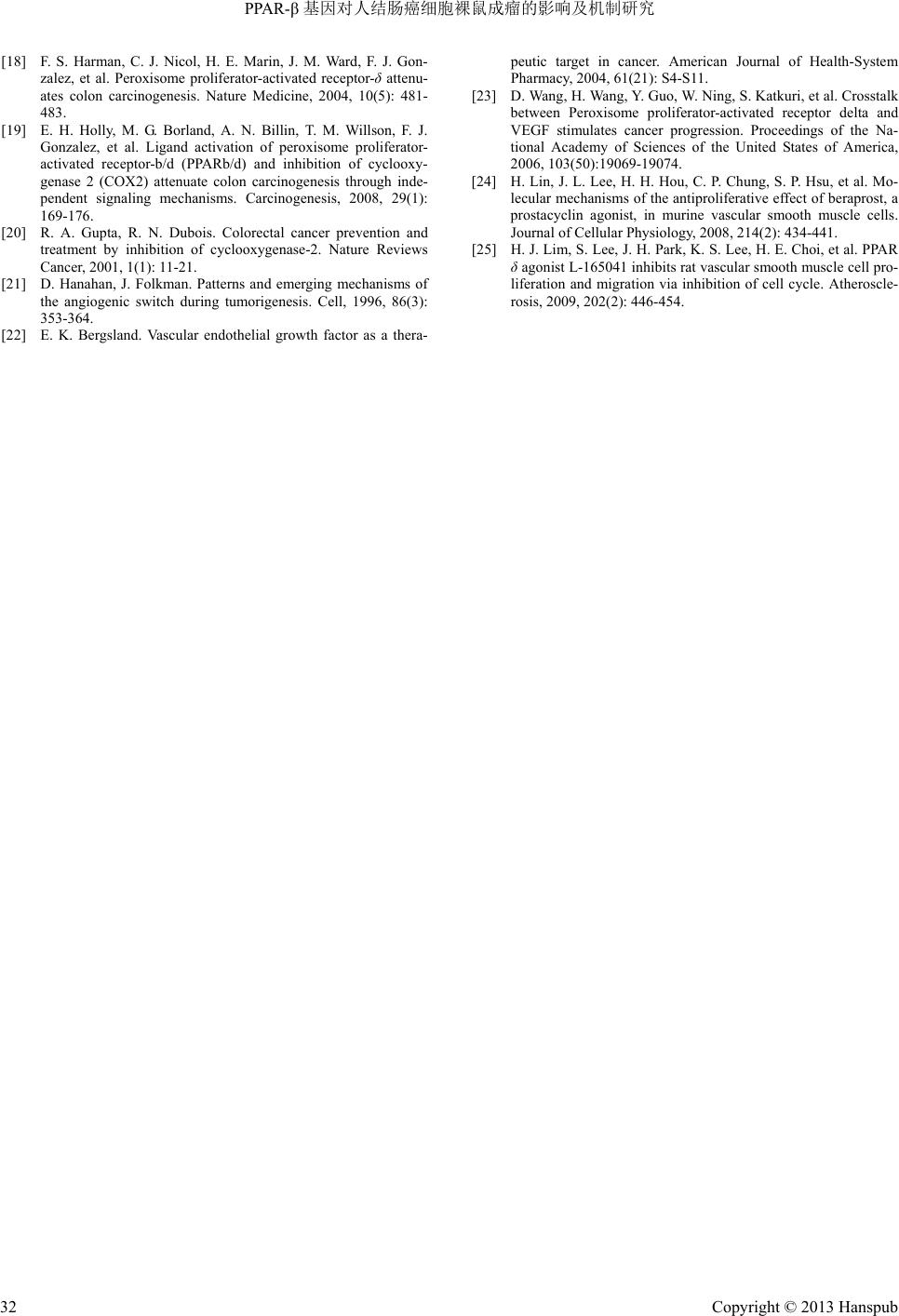

World Journal of Cancer Research 世界肿瘤研究, 2013, 3 24-32 http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/wjcr.2013.33005 Published Online July 2013 (http://www.hanspub.org/journal/wjcr.html) Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 24 Effect of PPAR-β Gene on Human Colon Cancer Growth in Vivo and Molecular Mechanism Qin Ma, Yongyang Yu, Cun Wang, Jin Zhou, Keling Chen, Lie Yang*, Zongguang Zhou# Digestive Surgery Laboratory, Department of Gastro-Intestinal Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu Email: #zhou767@163.com Received: Jun. 2th, 2013; revised: Jun. 10th, 2013; accepted: Jun. 23th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Qin Ma et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unre- stricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract: Objective: To explore the effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β (PPAR-β) gene on human colon cancer growth in vivo and the molecular mechanism. Methods: The models of colon cancer xenografts in nude mice were established by respectively subcutaneous injected human colon cancer cell line KM12C with PPAR β knockdown or untreated. The xenografts were measured daily and weighted 20 days later. The results of two groups were compared by immunohistochemisty (IHC). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was detected by real-time reverse-transcription (RT-PCR), IHC, Western blot. Meanwhile, KM12C cell was treated in vitro by using PPAR-β ago- nist GW501516 and then the relativity of the dose and VEGF was analyzed. Result: The xenografts in PPAR β-knock- down group grew significantly earlier and larger and they were more frequently less-differentiated compared to those in control group. Meanwhile, the expression of VEGF, either in xenografts or in KM12C cell line, was significantly higher in PPAR β-knockdown group than that in control group. Moreover, specific activation of PPAR β didn’t change the ex- pression of VEGF in the KM12C cells with PPAR β knockdown, while yielded a dose-dependent decrease of VEGF in those without PPAR β knockdown. Conclusion: These findings indicate that PPAR β may induce the differentiation and inhibit the growth of colon cancer, which may be associated with its inhibition effect on VEGF in colon cancer cells. Keywords: PPAR-β; Colon Cancer; Carcinogenesis; VEGF PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 马 钦,于永扬,王 存,周 锦,陈珂玲,杨 烈*,周总光# 四川大学华西医院,消化外科研究室,胃肠外科中心,成都 Email: #zhou767@163.com 收稿日期:2013 年6月2日;修回日期:2013 年6月10 日;录用日期:2013 年6月23 日 摘 要:目的:探讨过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体-β (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β, PPAR-β)对人结 肠癌细胞裸鼠移植瘤生长的影响及机制。方法:分别将 PPAR-β特异性沉默和野生型的人结肠癌细胞 KM12C 种 植于裸鼠背部皮下,动态监测移植瘤体积,20 天后取瘤体称重,免疫组化比较二者分化程度;荧光定量 PCR(RT- PCR)、免疫组化、Western blot检测体内外人结肠癌细胞血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)表达;此外,用 PPAR-β特 异性激动剂 GW501516 处理离体细胞,检测 VEGF与剂量的相关性。结果:PPAR-β沉默组的移植瘤生长速度 明显快于对照组,并且低分化肿瘤的比例、VEGF 表达水平显著高于对照组。特异性激活沉默组的 PPAR-β并没 有改变其 VEGF的表达,在对照组中则观察到 VEGF 水平与激活程度呈剂量相关性降低。结论:PPAR-β沉默 在移植瘤中发挥了促瘤作用,提示PPAR-β可能是结肠癌细胞的抑癌基因,并可伴有阻止 VEGF 表达的作用。 关键词:过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体;结肠肿瘤;肿瘤生长;血管内皮生长因子 *通讯作者。  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 25 1. 引言 过氧化物酶增殖物激活受体-β(PPAR-β)属于核激 素受体超家族[1,2],在人体各组织中广泛表达,在脑、 心、肾及结肠上皮细胞中高表达[3,4]。现有研究显示, PPAR-β在调节脂质代谢及能量平衡中扮演了重要角 色[5,6],并参与了胚胎着床、伤口愈合、炎症反应、内 皮细胞增殖、血管形成等生理过程[7,8]。He 等报道, PPAR-β在结肠癌中高表达,并且是 WNT 信号通路的 下游靶基因,APC 基因失活性突变后 PPAR-β高表达, 提示 PPAR-β可能参与了结肠癌的病理过程[9]。然而 , PPAR-β在结肠癌中的作用尚有争议,一些研究提示 它具有促进肿瘤生成的作用,而一些研究则获得了相 反的结论[10]。因此,亟需进一步研究揭示 PPAR-β在 结肠癌中的作用。在前期实验中,我们已采用慢病毒 介导的 RNA干扰技术(RNAi)建立了 PPAR-β特异性、 稳定沉默的人结肠癌细胞系 KM12C ,并且发现 PPAR-β可能具有促分化以及阻抑制结肠癌细胞增殖 的作用[11]。为进一步验证体外实验的结果,本研究采 用PPAR-β沉默及野生型的 KM12C 细胞分别建立结 肠癌裸鼠移植瘤模型,分析 PPAR-β沉默对于移植瘤 生长的影响及机制。 2. 材料和方法 2.1. 主要材料与试剂 人结肠癌细胞系 KM12C 由IJ Fidler教授(Anderson Cancer Center, TX)提供。实验组采用前期研究已建立 的PPAR-β稳定沉默KM12C 细胞[11],对照组为野生 型KM12C细胞。细胞被保存在含 Earle 氏盐,L-谷氨 酰胺,非必需氨基酸的 Eagle’s 最小必需培养基(MEM) 中(Sigma-Aldrich),补充有 1.5%碳酸氢钠,1 mm的 Na-丙酮酸(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA),1 × MEM 维生素(Invitrogen) ,1%青霉素-链霉素(Invitrogen),1 微克/毫升,嘌呤霉素(仅用于处理后的细胞,以保持 纯度)和10%胎牛血清(Invitrogen) 。 2.2. 实验动物的分组及处理 购自四川大学实验动物中心的24 只6周龄雌性 裸鼠分为 2组,每组 12 只。经腹腔内注射戊巴比妥 钠(65 mg/kg, Catalogue No.p3636, Sigma-Aldrich, Sweden) 麻醉后,分别在小鼠右肩皮下注射 PPAR-β 沉默或野生型KM12C 细胞(2 × 106个细胞/鼠100 μl PBS 液)。定期使用电子卡尺测量瘤体长径及宽径以监 测肿瘤生长,计算肿瘤体积:(长度 × 宽度 2)/2。20 天后处死裸鼠,测移植瘤体积及称重,并进行以下分 析。分析以随机双盲的原则进行。 2.3. 免疫组织化学检测(IHC) 采用免疫组织化学检测肿瘤的PPAR-β及VEGF 表达。免疫染色按 Envision 法进行[11],一抗为兔多克 隆抗 PPAR-β IgG 抗体(ARP37889, Aviva Systems Biology, CA)和小鼠单克隆抗-VEGF IgG抗体(ab68334, Abcam, MA)。聚合物-HRP标记的抗兔抗体作为二抗 (Dakocytomation, CA)。以仅接受一抗组作为阳性对 照,PBS 液作为阴性对照,在所有的染色过程中,阳 性对照均获得明显染色,阴性 对照均未 见染 色。IHC 切片采用随机双盲的原则由两位研究者(杨烈及马钦) 分别读片,按弱染色组及强染色组进行评分,对于染 色评分结果不一致者,共同评估后进行分类。 2.4. 实时定量RT-PCR 采用实时定量 RT-PCR 检测移植瘤 PPAR-β、 VEGF 的mRNA 表达水平。采用TurboCapture mRNA 试剂盒(Qiagen, Germany)提取总 RNA,应用高通量 cDNA 反转录试剂盒(Applied Biosystems, CA)进行逆 转录。反应在美国应用生物系统公司7500 实时 PCR 系统上进行,使用比较阈值循环(CT)方法(△△CT)进 行分析[11]。用于量化的mRNA 的引物和 TaqMan 探针 由表 1中列出。以甘油醛-3-磷酸脱氢酶(GAPDH)作为 内参(TaqMan 检测试剂,Applied Biosystems),每个样 品设三个副孔。 2.5. Western blot检测 按之前报道过的方式采用 Western blot检测 PPAR-β及VEGF 的蛋白质表达水平[10]。以 1 × RIPA 裂解液(Santa Cruz, CA)从肿瘤中提取总蛋白,以兔多 克隆抗 PPAR-β IgG抗体(ARP37889, Aviva Systems Biology, CA)和小鼠单克隆抗 VEGF IgG抗体(ab68334, Abcam, MA)为一抗。以辣根过氧化物酶(HRP)-多克隆 山羊抗兔 IgG 为二抗(0.1 µg/ml, DakoCytomation, Denmark),以 ECL 加Western 印迹可视化检测系统进 行观察(Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare, UK)。以  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 26 Table 1. Primers and probes used to quantify mRNA 表1. 引物及探针 mRNA mRNA 引物及探针 (F) 5’-CACATCTACAATGCCTACCT-3’ (R) 5’-CTTCTCTGCCTGCCACAATGTCT-3’ PPAR-β (P) 5’-FAM-AGAAGGCCCGCAGCATCCTCAC-TAMRA-3’ (F) 5’-TACTGCTGTACCTCCACCTCCACCATG-3’ (R) 5’-TCACTTCATGGGACTTCTGCTCT -3’ VEGF (P) 5’- FAM-TCACTTCATGGGACTTCTGCTCT-TAMRA -3’ PPAR,过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体,血管内皮生长因子,血管内皮生长 因子;ADRP,脂肪细胞分化相关蛋白,L-FABP,肝脏脂肪酸结合蛋白,F, 正向引物,R,反向引物,P,TaqMan 探针。 兔单克隆抗体的GAPDH 水平作为内参(0.04 µg/ml; Cell Signaling, MA)。 2.6. ELISA检测 使用 VEGF 比色法酶联免疫吸附测定试剂盒测定 无细胞上清液中 VEGF 的产量(Thermo Fisher Scien- tific Inc., Rockford, IL)。将沉默组及对照组的肿瘤细 胞分为 5组,每组 1 × 106个细胞,分别在无血清培养 基中培养 18 小时后,加入等量生理盐水及浓度分别 为1,2,4,8 μM的PPAR-β激动剂 GW501516 孵育 24 小时。取上清液按照生产商的说明进行 ELISA 检 测。样本在酶标仪(Anthos htⅢ, Austria)上以 450 nm 处测定各孔的颜色强度。校准曲线通过每个校准孔吸 光度值与样本浓度的比值获得。样品 VEGF的浓度统 一为纳克/106个细胞。 2.7. 统计分析 统计分析采用使用SPSS 13.0 软件进行 T-检验或 (如适用)卡方检验。实时荧光定量 RT-PCR 结果采用 相对软件表达工具-XL[5](REST-XL©-version 2) (http://www.wzw.tum.de/gene-quantification/)做基因表 达的相对定量统计学分析[12]。以P < 0.05 为差异有显 著水平。所有数据均设至少三个重复。 3. 结果 3.1. PPAR-β沉默组裸鼠移植瘤生长显著增快 如图 1(a)中所示,接种后 10天后 PPAR-β沉默组 即可检测到肿瘤生长,而对照组平均12天后才能被 观察到。且 PPAR-β沉默组的在各监测时点的体积均 显著高于对照组(P < 0.05)。接种 20 天后,沉默组的 肿瘤平均体积为对照组的 1.8倍(2.9 立方厘米与 1.6 立方厘米,P < 0.001;图 1(b)A),沉默组肿瘤的平均 (a) A B (b) (a) 移植瘤的生长曲线:接种后10 天后 PPAR-β沉默组即可检测到肿瘤生长, 而对照组平均 12 天后才能被观察到。且 PPAR-β沉默组的在各监测时点的 体积均显著高于对照组(P < 0.05)。(b) (A)观测终点移植瘤的体积大小;(B) 观测终点 PPAR-β沉默组的移植瘤重量明显大于对照组(5.1 ± 1.7 vs. 2.6 ± 0.98 g, P = 0.025)。 Figure 1. The growth of nude mice xenografts were promoted after PPAR-β knockdown 图1. 沉默PPAR-β可 促进裸鼠移植瘤的生长  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 27 重量为 5.1 ± 1.7 g 而对照组为 2.6 ± 0.98克(P = 0.025, 图1(b)B)。 3.2. 裸鼠移植瘤中 PPAR-β仍保持稳定沉默 为证实 PPAR-β的沉默效果是否在裸鼠体内仍存 在,我们进一步检测了移植瘤中 PPAR-β的表达。通 过免疫组化,我们发现,92%(11/12)沉默组的肿瘤 PPAR-β呈弱染色,而 83%(10/12)的对照组呈强染色 (P < 0.001;图 2(a))。实 时 定 量RT-PCR 证实沉默组的 PPAR-β mRNA 相比对照组表达显着减少 71.0%,(P = 0.021;图2(b))。Western blot 分析显示沉默组的 PPAR-β蛋白表达量明显低于对照组(P = 0.013;图 2(c))。 3.3. PPAR-β沉默组裸鼠移植瘤分化程度更差 通过免疫组织化学染色,我们发现 PPAR-β沉默 (a) (b)  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 28 (c) (a) 免疫组织化学染色:A:PPAR-β在移植瘤中的表达(棕色),×400 放大;B:92%的(11/12) PPAR-β沉默组呈现弱染色而 83%(10/12)的对照组表现为强染色(P < 0.001)。(b) 实时定量 RT-PCR 证实沉默组的 PPAR -β mRNA 相比对照组表达显着减少 71.0%(P = 0.021)。(c) Western blot 分析显示,A:沉默组的 PPAR-β蛋 白表达强度明显低于对照组;B:定量分析显示沉默组的 PPAR-β蛋白表达量明显低于对照组(P = 0.013)。 Figure 2. The expression of PPAR-β in the xenografts from nude mice 图2. 移植瘤的 PPAR-β表达 Low differentiated High differentiated (a) (b) Figure 3. The xenografts were less differentiated after PPAR-β knockdown 图3. PPAR-β沉默组移植瘤呈现更多去分化现象 组比对照组的低分化移植瘤例数显著高于对照组 (75%对17%,P = 0.022),表现为成团片状结构,较 少呈现出腺管状结构(图3)。 免疫组化显示:(a) PPAR-β呈弱染色的移植瘤显  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 29 示出更多去分化的现象,表现为成团片状结构,较少 呈现出腺管状结构,×400 放大。(b) PPAR-β沉默组的 低分化移植瘤例数显著高于对照组(75% vs. 17%, P = 0.022)。 3.4. PPAR-β沉默介导的 VEGF 表达 免疫组化显示,在沉默组与对照组移植瘤的上皮 细胞与间质细胞均有 VEGF 染色。与对照组相比, PPAR-β沉默组中 VEGF强染色的例数显著高于对照 组(67% vs. 33%,P = 0.040;图 4(a))。实时定量 RT-PCR 及western blot 显示,PPAR-β沉默组中 VEGF mRNA 及蛋白质水平均显著高于对照组(P < 0.05;图 4(b), (c))。 3.5. 激活 PPAR-β调低 KM12C 细胞 VEGF 的 表达 为进一步验证PPAR-β与VEGF 之间的关系,我 们用 PPAR-β特异性激动剂GW501516 处理 2组细胞 (a) (b)  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 30 (c) (a) 免疫组化显示 A:VEGF 在移植瘤中的表达(棕色),×400 放大;B:67% (8/12) PPAR-β沉默组的移植瘤 VEGF高表达 而 对照组仅 33% (4/12) (P = 0.040)。(b) 实时定量 RT-PCR 显示 PPAR-β沉默组的 VEGF高表达。(c) western blot分析显示 PPAR-β 沉默组的 VEGF 蛋白表达是对照组的2.5 倍(P < 0.05)。 Figure 4. VEGF expression of xenograft was increased after PPAR-β knockd own 图4. PPAR-β沉默组移植瘤的 VEGF 表达上调 KM12C细胞,提取上清液监测 VEGF水平。结果, 在接受 GW501516 处理前 PPAR-β沉默组的 VEGF分 泌明显高于对照组(P = 0.035;图 5) ;在应用 GW501516 后,对照组的 VEGF 分泌量随着使用量的 增加而减少(P = 0.018),然而在 PPAR-β沉默组却没有 明显变化(P = 0.83;图 5)。 接受 GW501516 处理前PPAR-β沉默组的 VEGF 分泌明显高于对照组(P = 0.035),在应用 GW501516 后,对照组的 VEGF 分泌量随着使用量的增加而减少 (P = 0.018),然而在 PPAR-β沉默组却没有明显变化(P = 0.83)。 4. 讨论 PPAR-β在结肠癌病理过程中的作用尚有争议 [10]。在本研究中,我们通过建立裸鼠移植瘤模型发现, PPAR-β沉默组移植瘤比对照组生长的更快、分化程 度更低,同时 PPAR-β沉默组的 VEGF表达无论在移 植瘤上还是在离体的 KM12C 细胞上都显著上调; PPAR-β特异性激动剂作用于野生型 KM12C细胞可 显著下调 VEGF分泌量,并呈现剂量依赖性,而 PPAR- β沉默后的细胞则无明显变化。本研究提示,PPAR-β 在活体中具有抑制结肠癌生长的作用,而参与促进肿 瘤分化、抑制VEGF 表达是其可能的作用机制。 近年研究提示,PPAR-β可能参与了多种上皮细 胞的分化调节过程。例如,PPAR-β特异性激活促进 了角质细胞分化[13-15],并可能参与了消化道隐窝潘氏 Figure 5. KM12C cells secreted less VEGF after PPAR-β activation 图5. PPAR-β特异性激活后对照组 KM12C 细胞VEGF 分泌减少 细胞的分化调控[16]。我们的前期研究显示,PPAR-β 沉默可诱导结肠癌细胞逆向分化,而人直肠癌组织中 PPAR-β高表达与直肠癌细胞分化良好程度正相关, [11] 提示 PPAR-β可能具有促进结肠癌细胞分化的作用。 在本研究中,我们进一步对活体中 PPAR-β对结肠癌 分化的影响进行观察,结果发现,PPAR-β沉默组移 植瘤呈现了明显的逆向分化。该结果与我们前期的体 外实验结果一致,共同提示,该基因参与了促进结肠 癌细胞分化的作用。 Park 等[17]报道,应用 PPAR-β缺失的结肠癌HCT- 116 细胞在裸鼠的成瘤能力下降,提示 PPAR-β可能 具有促进结肠癌生长的作用。然而,近期研究显示,  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 31 与野生型鼠株相比,PPAR-β缺陷型小鼠更容易形成 结肠息肉,提示 PPAR-β具有抑制结肠癌生长的作用 [18,19]。我们前期细胞实验发现,PPAR-β沉默后结肠 癌细胞增殖力显著升高。在本研究中,我们进一步在 活体中观察 PPAR-β沉默对结肠癌生长的影响,结果 发现,PPAR-β沉默后移植瘤的生长明显加快,提示 PPAR-β可能在活体抑制结肠癌生长,与我们的体外 实验的结果一致。 血管生成是肿瘤生长的重要条件,当肿瘤生长至 1~2 mm³后将刺激宿主形成肿瘤血管[20]。VEGF 在血 管生成中具有关键作用,肿瘤可分泌包括VEGF在内 的多种细胞因子直接或间接的诱导血管生成,促使附 近血管的内皮细胞出芽并形成新的血管,为肿瘤生长 提供血供[21,22]。近期研究显示,激活 PPAR-β可上调 结肠癌细胞中VEGF 的表达,提示PPAR-β可能通过 促进 VEGF 影响血管生成[23]。然而,近期其他研究提 示,PPAR-β可能在多种组织中具有抑制血管内皮细 胞生长的作用[8,24,25]。本研究中发现,PPAR-β沉默可 促进离体及活体KM12C 细胞的 VEGF分泌,PPAR-β 特异性激活可显著抑制VEGF 分泌。提示PPAR-β可 能通过下调 VEGF 表达抑制结肠癌的血管生成,从而 抑制肿瘤生长。目前为止,我们还难以解释现有研究 的差异,因为它们的研究背景是如此的不同,所有相 异的结果可能受到了诸如实验策略,细胞类型、PPAR- β的表达水平,乃至细胞状态的影响。 综上,我们在裸鼠成瘤实验中发现 PPAR-β沉默 具有去分化及促进结肠癌细胞生长作用。体内外实验 证实,PPAR-β沉默可上调 VEGF 表达。此外,PPAR-β 沉默组细胞的 VEGF分泌没有受到 PPAR-β激动剂的 影响,而对照组分泌呈剂量依赖性下降。这些结果表 明,PPAR-β在体内可诱导结肠癌去分化和抑制其生 长,这与我们以前的体外研究结果相一致。其分子机 制可能通过减低 VEGF 表达进而抑制血管生成得以实 现。该研究为 PPAR-β激动剂在结肠癌预防和/或治疗 提供了理论支持。 5. 致谢 感谢 I.J. Fidler 教授 (Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX)提供 KM12C细胞系,本项目受国家自然 科学基金(No. 30801332; http://www.nsfc.gov.cn/)支持。 参考文献 (References) [1] S. A. Kliewer, B. M. Forman, B. Blumberg, E. S. Ong, U. Borg- meyer, et al. Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,1994, 91(15): 7355-7359. [2] E. E. Girroir, H. E. Hollingshead, P. He, B. Zhu, G. H. Perdew, et al. Quantitative expression patterns of peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-b/d (PPARb/d) protein in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2008, 371(3): 456- 461. [3] M. Uhlén, E. Björling, C. Agaton, C. A. Szigyarto, B. Amini, et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 2005, 4(12): 1920- 1932. [4] L. Berglund, E. Björling, P. Oksvold, L. Fagerberg, A. Asplund, et al. A genecentric human protein Atlas for expression profiles based on antibodies. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 2008, 7(10): 2019-2027. [5] C. H. Lee, P. Olson, A. Hevener, I. Mehl, L. W. Chong, et al. PPARdelta regulates glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(9): 3444-3449. [6] P. A. Grimaldi. Metabolic and nonmetabolic regulatory functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor b. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 2010, 21(3): 186-191. [7] J. M. Peters, F. J. Gonzalez. Sorting out the functional role(s) of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta/delta (PPAR- beta/delta) in cell proliferation and cancer. Biochimica et Bio- physica Acta, 2009, 1796(2): 230-241. [8] B. P. Kota, T. H. Huang and B. D. Roufogalis. An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacological Research, 2005, 51: 85-94. [9] T.-C. He, T. A. Chan, B. Vogelstein and K. W. Kinzler. PPARd is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell, 1999, 99(3): 335-345. [10] L. Yang, H. Zhang, Z. G. Zhou, H. Yan, G. Adell, et al. Biologi- cal function and prognostic significance of peroxisome prolif- erator-activated receptor {delta} in rectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 2011, 17(11): 3760-3770. [11] L. Yang, B. Olsson, D. Pfeifer, J. I. Jönsson, Z. G. Zhou, et al. Knockdown of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta induces less differentiation and enhances cell-fibronectin adhe- sion of colon cancer cells. Oncogene, 2010, 29(4): 516-526. [12] L. Yang, Z. G. Zhou, H. Z. Luo, B. Zhou, Q. J. Xia, et al. Quan- titative analysis of PPARdelta mRNA by real-time RT-PCR in 86 rectal cancer tissues. European Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2006, 32(2): 181-185. [13] M. Schmuth, C. M. Haqq, W. J. Cairns, J. C. Holder, S. Dorsam, S. Chang, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)- beta/delta stimulates differentiation and lipid accumulation in keratinocytes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 2004, 122 (4): 971-983. [14] A. D. Burdick, D. J. Kim, M. A. Peraza, F. J. Gonzalez, J. M. Pe- ters. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ in epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Cell Signal, 2006, 18(1): 9-20. [15] D. J. Kim, M. T. Bility, A. N. Billin, T. M. Willson, F. J. Gon- zalez, et al. PPAR-β/δ selectively induces differentiation and in- hibits cell proliferation. Cell Death & Differentiation, 2006, 13: 53-60. [16] F. Varnat, B. B. Heggeler, P. Grisel, N. Boucard, I. Corthésy -Theulaz, et al. PPAR-β/δ regulates paneth cell differentiation via controlling the hedgehog signaling pathway. Gastroenterol- ogy, 2006, 131(2): 538-553. [17] B. H. Park, B. Vogelstein and K. W. Kinzler. Genetic disruption of PPARd decreases the tumorigenicity of human colon cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001, 98(5): 2598-2603.  PPAR-β基因对人结肠癌细胞裸鼠成瘤的影响及机制研究 Copyright © 2013 Hanspub 32 [18] F. S. Harman, C. J. Nicol, H. E. Marin, J. M. Ward, F. J. Gon- zalez, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-δ attenu- ates colon carcinogenesis. Nature Medicine, 2004, 10(5): 481- 483. [19] E. H. Holly, M. G. Borland, A. N. Billin, T. M. Willson, F. J. Gonzalez, et al. Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-b/d (PPARb/d) and inhibition of cyclooxy- genase 2 (COX2) attenuate colon carcinogenesis through inde- pendent signaling mechanisms. Carcinogenesis, 2008, 29(1): 169-176. [20] R. A. Gupta, R. N. Dubois. Colorectal cancer prevention and treatment by inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2001, 1(1): 11-21. [21] D. Hanahan, J. Folkman. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell, 1996, 86(3): 353-364. [22] E. K. Bergsland. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a thera- peutic target in cancer. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 2004, 61(21): S4-S11. [23] D. Wang, H. Wang, Y. Guo, W. Ning, S. Katkuri, et al. Crosstalk between Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta and VEGF stimulates cancer progression. Proceedings of the Na- tional Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(50):19069-19074. [24] H. Lin, J. L. Lee, H. H. Hou, C. P. Chung, S. P. Hsu, et al. Mo- lecular mechanisms of the antiproliferative effect of beraprost, a prostacyclin agonist, in murine vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2008, 214(2): 434-441. [25] H. J. Lim, S. Lee, J. H. Park, K. S. Lee, H. E. Choi, et al. PPAR δ agonist L-165041 inhibits rat vascular smooth muscle cell pro- liferation and migration via inhibition of cell cycle. Atheroscle- rosis, 2009, 202(2): 446-454. |