Advances in Psychology

Vol.08 No.03(2018), Article ID:24272,14

pages

10.12677/AP.2018.83055

Nightmare Impacts Mental Health: The Moderation from Neuroticism Trait

Zhengyu Yang

Department of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing

Received: Mar. 16th, 2018; accepted: Mar. 22nd, 2018; published: Mar. 29th, 2018

ABSTRACT

Nightmare is characterized of its stressful and terrifying dream content, as a form of sleep disorders accompanied by the annoying daytime complications such as being anxious and experiencing overwhelming fear. So far, we have very little insight yet in understanding the mechanism underlying nightmare and its impact on mental health. For testing the applicability of the Affect Network Dysfunction model proposed by Levin (2009), we collect and match 56 subjects into 4 groups according to their monthly nightmare frequency, and we select two indexes for measuring the mental health, namely the well-being and Negative Affect; two indexes, Neuroticism and Negative Affect Sensitivity, to represent the Affect Stress as the moderator construct in the model. Firstly, the confounding effect from age and gender on nightmare frequency is consistent with previous studies. Our results indicate that the nightmare frequency is closely relate to the degree of subject’s perceived stress in life, and high nightmare frequency will damage on well-being and foster more negative effect. Whereas the negative effect had shown relatively more sensitivity in response to nightmare frequency than the well-being did. We also found that only the neuroticism could serve as the moderator to manipulate the relationship between nightmare and negative effect. This study has specified the significance of person’s trait in moderating the impact that nightmare frequency incur on people’s mental health, shedding a light on its relevant clinical application for the treatment and classification of nightmare.

Keywords:Nightmare Frequency, Mental Health, Affect Network Dysfunction Model, Neuroticism

噩梦影响心理健康:神经质的调节作用

杨正宇

西南大学心理学部,重庆

收稿日期:2018年3月16日;录用日期:2018年3月22日;发布日期:2018年3月29日

摘 要

噩梦是内容恐怖,令人毛骨悚然的梦,是一种引起焦虑恐惧为主要表现的睡眠障碍。目前,对噩梦如何影响心理健康我们还知之甚少,本研究我们收集了56名噩梦频次不同的健康被试,旨在验证Levin (2009)提出情感网络失调模型对噩梦影响心理健康机制的理论构想。我们选择了两类不同的心理健康指标:主观幸福感和负性情绪;以及两类不同的潜在情感困扰指标作为调节变量:负性情感敏感性和神经质人格。结果表明噩梦的频发的确与生活中压力息息相关,并且影响主观幸福感和负性情绪的多少。但是负性情绪在回归分析和方差分析中显示出更好的敏感度。而在情感困扰的指标上只有神经质人格可以通过调节作用在噩梦频率和负性情绪之间产生交互效应。同时我们还发现了噩梦报告频率在性别和不同年龄段上的差异。本研究揭示了噩梦影响心理健康的人格作用机制,可能对噩梦相关心理障碍的诊疗提供帮助。

关键词 :噩梦频率,心理健康,情感网络失调模型,神经质

Copyright © 2018 by author and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

1.1. 噩梦

1.1.1. 噩梦的定义

噩梦(nightmare)是通常意义上是指内容恐怖的梦,一种能引起焦虑恐惧的睡眠障碍,对我们的睡眠质量(Simor, Horvath, Gombos, Takacs, & Bodizs, 2012)和心理健康都具有深刻影响的睡眠现象。恶梦在儿童中多见,可发生于任何年龄。美国精神病学会(DSM-5, 2013)和睡眠医学会(ICSD-3, 2014)都对噩梦给出了相似的定义。噩梦通常从普通的梦境发展而来,因其负性情绪色彩的梦境内容过于强烈,导致个体从睡梦中惊醒,醒后伴随着一定程度的生理反应并对噩梦的记忆清晰。噩梦中的主导情绪以恐惧居多,有时也会是以愤怒,厌恶,悲伤,愧疚等为主题(Zadra, Pilon, & Donderi, 2006)。在更广大众理解中,噩梦常常还包括坏梦(bad dream)和夜惊(sleep terror)。但研究者发现夜惊(Oudiette et al., 2009)发生于非快速眼动睡眠(NREM)阶段,并且缺少噩梦丰富和鲜活的情节特征,个体在惊醒后有回忆上的困难。而坏梦不同于噩梦,坏梦被定义为那些有着负性梦境基调,却不曾唤醒个体的REM阶段的梦(Zadra & Donderi, 2000; Zadra et al., 2006)。坏梦和噩梦的产生机制被认为是一样的(Levin & Nielsen, 2009),同属于不安的梦(disturbed dreaming),区别是个体有没有被更强烈的负性梦境吓醒。

1.1.2. 噩梦的发生率

因为过往研究对噩梦的定义不是很严谨和统一,所以目前所积累的调查结果可以认为是粗略混合着坏梦和噩梦的数据。在普通人群中,约85%的人在过去一年中至少经历过一个噩梦(Levin, 1994);8%~29%的人回忆自己每个月都会经历噩梦(Levin & Nielsen, 2007; Ohayon, Morselli, & Guilleminault, 1997);2%~6%的受访者报告自己每周都会做噩梦(Bixler, Kales, Soldatos, Kales, & Healey, 1979; Levin, 1994; Schredl, 2010)。在年轻人和儿童,以及女性群体中噩梦较为多发(Nielsen, Stenstrom, & Levin, 2006)。对于儿童,成长中认知能力的发展才使得噩梦开始具备其高发的基础(Mindell & Barrett, 2002; Nielsen et al., 2000),而学龄前的儿童经历噩梦的机率较小(Simard, Nielsen, Tremblay, Boivin, & Montplaisir, 2008)。对于老年人,噩梦的发生率也明显得到下降(Nielsen et al., 2006; Salvio, Wood, Schwartz, & Eichling, 1992)。女性在各个年龄段都比男性平均报告更多得噩梦(Claridge, Clark, & Davis, 1997; Schredl, 2010; Tanskanen et al., 2001),且在回归了梦境报告频率后,差异仍然存在(Nielsen et al., 2006)。但近来元分析表明噩梦的两性差异仅在青年和成年后体现,且受多种中间变量的影响(Schredl & Reinhard, 2011)。同时值得注意的是噩梦的发生率一定程度上受到基因的调控(Hublin, Kaprio, Partinen, & Koskenvuo, 1999)。

1.1.3. 噩梦数据的收集方法

对梦境包括噩梦的数据收集一直是以自我报告(self-report)的形式进行的。其中又分为回顾估计式(retrospective estimate)和跟踪调查式(prospective log)。回顾式收集的数据类型多种多样(Gehrman, Matt, Turingan, Dinh, & Ancoli-Israel, 2002; Levin & Nielsen, 2007);跟踪式的睡眠日记可以自陈(narrative)的方式记录,也可以根据事先设计好的选项列表(checklist)进行勾选。不同收集方式的结果差异跟个体本身梦境报告的频率也息息相关,多梦的个体倾向于超出实际地高估自己的做梦频率(Schredl, 2002)。因为睡眠的过程涉及到意识状态的转变和认知能力的中断,自我报告式的方法在睡眠相关的数据收集上存在着比较大的信效度质疑(Gehrman et al., 2002),但是一项利用可穿戴的智能设备的验证性研究(Wolfson et al., 2003),证明了人们对睡眠状况的估计还是十分精准的。常用的PSQI量表更是获得了广泛的认可和应用,得到了良好的信效度检验(Backhaus, Junghanns, Broocks, Riemann, & Hohagen, 2002; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989)。相比于每天跟进的睡眠日记的跟踪,回顾式的方法往往低估了真实的噩梦和坏梦的频率(Robert & Zadra, 2008; Wood & Bootzin, 1990)。因为后者每天跟进,所以它被一致认为更能真实地反应个体的噩梦频率。但是值得注意的是睡眠日记得到的数据也不是绝对真实,因为它只代表一个时间窗口内的噩梦发生率,用它进行估计一整年还是会出现误差,例如调查的窗口内和之前时间遇到过多的应激事件,就会导致噩梦的数量骤升。对于回顾式研究者需注意参考时间点的设置,如每日,每周,每月,每年,不同的时间参考窗口常常也会导致不一致的发现(Miró & Martínez, 2005; Robert & Zadra, 2008)。

1.2. 噩梦与心理健康

大量的研究都表明噩梦的频率和个体负性情绪调节与心理健康息息相关,噩梦带给患者不尽的困扰(Levin & Nielsen, 2007, 2009)。临床上各种心理疾病都与居高不下的噩梦发生率相关,如焦虑症(Nielsen et al., 2000; Levin & Hurvich, 1995; Spoormaker, Schredl, & van den Bout, 2006);抑郁症(Blagrove, Farmer, & Williams, 2004; Miró & Martínez, 2005; 叶碧瑜, 苗国栋, 李烜, & 徐贵云,2009);精神分裂症(Hartmann & Russ, 1979; Levin, 1998; Watson, 2001);自杀倾向(Nadorff, Nazem, & Fiske, 2011; Sjöström, Wærn, & Hetta, 2007; Tanskanen et al., 2001);创伤后应激障碍(Germain & Nielsen, 2003;杨赛花 & 李晓驷,2011)。同时在噩梦的高发群体中,它们的整体睡眠质量和结构都会发生负面的变化,伴随着更加不稳定的睡眠状态和其他睡眠障碍(Germain & Nielsen, 2003; Levin, 1994; Simor, Horvath, Gombos, Takacs, & Bodizs, 2012; Simor et al., 2014);并且影响到他们日间的认知决策能力(Köthe & Pietrowsky, 2001; Pietrowsky & Köthe, 2003)。噩梦的频率对个体的心理疾病的出现,互相有一定的长时程的预测能力,例如研究表明在青少年中13岁出现的焦虑症症状可以预测其3年后的噩梦频率(Nielsen et al., 2000);另一团队发现个体的噩梦频率可以预测其两年后的自杀倾向(Sjöström, Hetta, & Waern, 2009)。

1.3. 噩梦的理论模型

过去近百年的噩梦研究,为噩梦的产生机制和如何对人们的心理健康造成影响,提出过许多种理论模型试图进行解释(Nielsen & Levin, 2007; 朱华珍, 2006)。如经典和新精神分析学派的冲突模型,图像具化(Image contextualization)模型(Hartmann, 1996, 1998),进化论取向的危险模拟(threat simulation)模型(Revonsuo, 2000),以及情绪调节(mood regulation)模型(Kramer, 1991)等。而最近提出的情感网络失调(Affect Network Dysfunction, AND)模型综合了以往各个模型的特点,并结合神经科学对情绪调节的脑网络的研究成果,在多个维度讨论噩梦的影响和发生机制(Levin & Nielsen, 2007, 2009; Nielsen & Levin, 2007)。该模型认为噩梦和坏梦,尤其当其发生在REM阶段时,大脑是在利用这个机会通过重激活和重新绑定新的梦境物体和场景,执行着条件性恐惧的消退(conditioned fear extinction)功能, 这一观点得到了恐惧相关的动物模型研究(Lang, Davis, & Öhman, 2000; LeDoux, 2000)已经睡眠成像研究的支持(Hobson, Pace-Schott, & Stickgold, 2000)。REM睡眠中对边缘系统的激活(Dang-Vu et al., 2007)支持了该理论提出的梦境中负性情绪调节的神经机制AMPHAC (amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex)。而噩梦正是过度的调节任务导致个体无法承受而被惊醒的结果。当这样的线下(off-line)情绪调节经常性得以失败告终时,打破了平衡,就促使导致与高噩梦发生率相关的各种心理疾病的产生。该理论还总结出来重要的两个影响因素(Levin & Nielsen, 2009):情感负荷(affect load)和情感困扰(affect distress)。情感负荷指的是生活中负性情绪和压力事件的积累和总和,被认为是一种状态因素(state factor)。噩梦的高发总是和个体生活中的充满压力事件息息相关(Cartwright, 1991; Picchioni et al., 2002; Wood, Bootzin, & Rosenhan, 1992; Woodward, Arsenault, Murray, & Bliwise, 2000),而短暂出现的轻微压力源也会使噩梦的频率暂时性地上升(Duke & Davidson, 2002; Kroth, Thompson, Jackson, Pascali, & Ferreira, 2002),而随着压力源的消失,噩梦也不再多发。Levin和Nielsen认为情感负荷是影响个体不安的梦发生频率的关键因素。而情感困扰是一种特质因素(trait factor),是个体长期具有的对负性情绪刺激的知觉和反应倾向,与神经质(neuroticism)的人格特质有很大的重叠(Nielsen & Levin, 2007; Watson & Pennebaker, 1989)。由于高发的噩梦给患者的生活带来更多负性的情绪刺激,具有情感困扰特征的个体对这些刺激极为敏感,在长时间的恶性循环下产生对心理健康之间的影响。Belicki首先发现对噩梦带来困扰(nightmare distress)的感知与心理健康的相关比噩梦频率本身大得多(Belicki, 1992)。后续研究(Levin & Fireman, 2002)发现当控制了被试在情感困扰这一特质因素后,噩梦频率和心理健康之间的关系几近不存在了。相似的结果在许多独立的实验室研究中得到验证(Blagrove et al., 2004; Miró & Martínez, 2005; Roberts & Lennings, 2006)。这种类似神经质的情感困扰特质本身即和各种心理疾病存在潜在的联系(Hartmann, Elkin, & Garg, 1991; Levin, 1994)。尽管该理论的提出得到了大多数过往实验的支持但是,由于缺乏前瞻的设计,在各个团队独立的研究中,因变量的选择上标准不一。虽然都是在考察心理健康相关的指标,但是有的研究更加关注幸福感(well-being)指标(Blagrove et al., 2004; Zadra & Donderi, 2000),而有的研究者倾向选择精神病理学(psychopathology)相关的指标作为因变量(Antunes-Alves & De Koninck, 2012; Pesant & Zadra, 2006)。同时在上述模型中,对情感困扰这一特质因素的定义,有意与过去人格研究中的神经质人格区分开来,强调其在遇到负性刺激时的反应倾向,而不是即成结果(Nielsen & Levin, 2007)。然而在过往研究中,选用不同的情感困扰指标也是导致不同的实验结果的潜在影响因素。因此本研究旨在希望通过结合自己的数据和云端上美国的人类脑连接组计划(human connectome project,HCP)的大数据来验证该理论中两个主要影响因子情感负荷和情感困扰的实际作用,同时探寻在情感困扰和心理健康相关指标中,哪一种指标是对该模型最敏感及解释力最强的,借以帮助我们更好得理解噩梦产生的机制和其影响心理健康的途径。

2. 方法

2.1. 数据来源

本研究数据采用HCP(https://wiki.humanconnectome.org/display/PublicData/Home),人类脑连接组计划。这些数据是一份囊括了基本的人口学变量和家庭背景,精神状态与精神病史,认知与情绪的行为实验测试,人格量表,脑成像数据等的庞大云存储资料库。该研究学习使用网络大数据即节约研究成本,又充分体现了当下数据公开,可重复检验,互相合作的研究趋势(Poldrack & Gorgolewski, 2014)。

2.2. 数据选取

以上述的情感网络失调模型中的各个关键因素为关注点,我们选择了压力感问卷(Perceived Stress Scale)对个体生活中综合知觉到所存在的压力程度进行测量,即模型中的情感负荷因素;而模型中的特质因素,情感困扰,我们选取了两种测量方法。一种是自下而上的,表现在认知倾向上的负性情绪敏感性,由宾大情绪识别测验(The Penn Emotion Recognition Test)中的对愤怒,恐惧,悲伤三种情绪的行为成绩所测得;另一种选择是自上而下单纯的人格特质:由大五人格中的神经质特质一项的得分表示。对于模型中因变量心理健康程度的测量,一类我们选用NIH toolbox中的well-being量表中的,生活满意度(Life Satisfaction),自我价值感(Meaning and Purpose),正向情绪(Positive Affect)这三个指标作为个人主观幸福感的指标,它代表的是长期的更为宏观正向的心理健康程度;而另一选择是体现近期中个体所知觉到的负性情绪,由NIH toolbox负性情绪测量问卷下的愤怒情绪(Anger-Affect Survey),恐惧情绪(Fear-Affect Survey),悲伤情绪(Sadness Survey)三个子量表所组成。其他涉及到的变量还有:匹兹堡睡眠量表(PSQI)中的每周坏梦次数作为自变量噩梦频率的指标,以及性别,年龄等人口学数据。虽然之前的研究明确定义把被试惊醒的噩梦,能更有效的对幸福感进行预测,但之前研究并没有考虑到分离噩梦和坏梦的概念后,坏梦的相对多少也会产生变化。并且另有研究表明其实坏梦比噩梦有更好的预测能力(Zadra, Assaad, Nielsen, & Donderi, 1995; Zadra, Donderi, & Assaad, 1991)。因为研究者普遍认为两者的产生机制是一致(Levin & Nielsen, 2009),所以我们选取的坏梦一项,在没有特指和定义是噩梦还是坏梦时,反而是噩梦和坏梦的合集。这一选择并不损害其应有的噩梦的效应,也更能反应两种负性梦境的综合影响能力。因为匹兹堡睡眠量表中噩梦频率的分布过于极端,我们根据最少也是最难收集的每周噩梦次数大于等于3次的噩梦频率极端组的人口学变量进行重新的匹配,每一个噩梦频率都选出14名被试,最终总共匹配所得被试56名,男性24名,女性32名,平均年龄25.5岁。

2.3. 分析方法

使用spss 20.0统计软件进行的描述统计、主成分分析的方法进行降维、独立样本t检验、One-Way Anova的方差分析以及LSD的方法进行事后两两比较、皮尔逊和斯皮尔曼相关分析、逐步多元回归分析以及应用AMOS结构方程软件为调节模型进行验证分析。

3. 结果

3.1. 描述性统计

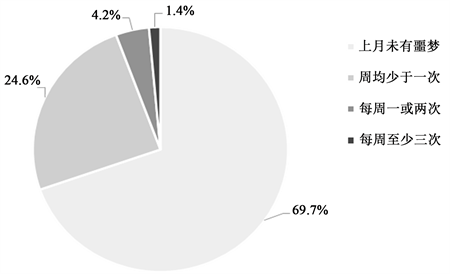

如图1所示,对HCP数据库中所有970名被试的噩梦报告频率进行描述性分析可见,上月未有噩梦,周均少于一次,每周一或两次,每周至少三次的人群依次占比:69.7%,24.6%,4.2%,1.4%。如表1所示,在性别上(删除一名性别认知不明的被试)的独立样本t检验显示男女之间在噩梦频率上差异显著。在不同的年龄段之间进行One-Way ANOVA方差分析,结果显示年龄主效应显著(表2),事后的两两比较表明差异主要是存在于22~25的人群与26~35岁的人群之间,见表3。

Figure 1. The frequency of the nightmare report in primary data (n = 970)

图1. 原始数据中噩梦的报告频率(n = 970)

Table 1. The gender difference in the frequency of the nightmare report

表1. 噩梦的报告频率在性别上的差异

*p < .05; **p < .001.

Table 2. The difference of four age groups in the frequency of the nightmare report

表2. 噩梦的报告频率在四个年龄段(岁)上的差异

*p < .05; **p < .001.

Table 3. The LSD of the difference of four age groups in the frequency of the nightmare report

表3. 噩梦报告频率在年龄段(岁)上差异的事后检验p值表(LSD)

*p <.05; **p <.001, (2-tailed).

3.2. 分析结果

基于匹配过后的56名被试,我们进行了针对情感网络失调模型的验证分析。首先对由一阶潜变量构成的二阶潜变量主观幸福感,和负性情绪进行信度和效度的检验,见表4。由于两者各自由三个子维度构成,只进行了效标效度的检验,通过计算各自三个项目的总分,再与子维度进行相关分析,可以看出,两者都只与自己的子维度呈现高相关。而信度检验的克隆巴赫系数都大于0.7,说明两者的信度都得到保证。

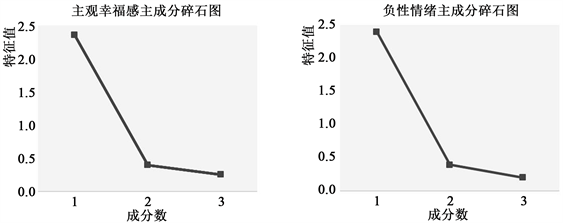

为方便之后的分析,同时更好的综合体现主观幸福感和负性情绪两个指标的水平,我们分别对两种进行了主成分分析降维。由表5可知KMO指数都大于0.7,适合进行因子分析,其巴特利特球度检验统计量的观测值相应的概率都p值接近0,小于显著性水平(取0.05)。由图2可知两者主成分分析的结果都

Figure 2. The principal component analysis of two mental health related variable

图2. 两类心理健康相关变量的主成分分析图

Table 4. The related validity and validity analysis of two mental health related Second order latent variable (n = 964)

表4. 两类心理健康相关的二阶潜变量的关联效度与信度分析(n = 964)

*p < .05; **p < .001, (2-tailed).

Table 5. The principal component factor analysis of two mental health related variable

表5. 两类心理健康相关的因变量的主成分因子分析

*p < .05; **p < .001, (2-tailed).

显示只有一个成分的特征值大于1,符合我们的预期。分别能够解释的总方差变异为78.4%和79.11%,属于可接受范围。并分别将降维后的得分保存为以主观幸福感和负性情绪命名的两个新变量。

之后对压力感和两个心理健康相关的新变量以及各自底下的子变量在不同噩梦频率上做方差分析,见表6。结果表明除了正向情绪仅到达边缘显著F(3 52) = 2.4,p = 0.078,其他各个因变量都达到了显著水平,说明了噩梦频率在其的主效应存在。分别对主要关注的压力感,主观幸福感和负性情感进行事后分析,结果表明差异主要存在于噩梦频率为每周大于三次组和其他组之间,但在负性情绪的结果中,我们发现每周一或两次组也和其他更少频率的组别存在显著差异,见表7。

Table 6. The different of pressure and mental health related variable in different nightmare report frequency

表6. 压力感与心理健康相关变量在不同噩梦的报告频率的差异

Table 7. The LSD of the different of pressure, subjective well-being and negative emotion in different nightmare report frequency

表7. 压力感,主观幸福感和负面情绪在噩梦频率上的差异的事后检验p值表(LSD)

除了神经质人格外,作为另外一个我们感兴趣的需要构建的,用来反映情感困扰的指标是负性情绪的敏感性。所以我们对宾夕法尼亚大学情绪识别测中的对愤怒,恐惧,悲伤三种情绪面孔的行为成绩进行相似的主成分降维分析(分别在被试水平各种减去了被试对中性面孔识别的成绩)。其KMO指数和巴特利特球度检验都负荷标准,同样只提取出一个主成分。存储为新变量负性情绪敏感性。之后我们进行了为验证模型所选取的四类变量间以及与噩梦频率的相关分析,如表8,结果显示除了负性情感敏感性和其他四个变量间不存在相关关系,其他变量间都存在一定的相关关系(涉及噩梦频率的相关分析使用斯皮尔曼等级相关,其余为皮尔逊相关)。

之后我们结合引言中提出的理论模型,分别针对因变量主观幸福感和负性情绪(心理健康),自变量噩梦频率以及调节变量神经质人格和负性情绪敏感性(情感困扰)进行了多元回归方程分析,见表9。主要的结果是,只有神经质人格和的噩梦频率的交互项能显著地预测因变量负性情绪。其β值为0.22,使得R2显著增加0.045,并使得噩梦频率对负性情绪失去预测能力。对回归结果的解读请看讨论部分。最后我们用AMOS 20.0软件进行了结构方程的验证分析,可见图3,其拟合优度可见表10,其中X2/df = 1.38,p = .23 > .05,说明该模型与默认的最优模型没有差异,同时拟合优度(goodness-of-fit)指标中CFI,TLI均.90,而RMSEA大于.05,说明该模型具有很好的拟合度。

Table 8. The correlation coefficient of the prime variables

表8. 主要关注变量间的相关系数表

*p < .05; **p < .001, (2-tailed).

Table 9. The regression equation test of two dependent variables and two regulated variables

表9. 两类因变量与两类调节变量的回归方程检验

*p < .05; **p < .001, (2-tailed).

Table 10. The fitting optimization parameters of the structural equation in Figure 3

Figure 3. The path of structural equation of neurotic personality and nightmare frequency

图3. 神经质人格以及其与噩梦频率的交互相对负性情绪的结构方程路径

4. 讨论

4.1. 噩梦的发生率及性别与年龄对其的影响

首先在我们的原始数据的描述性结果中,每周噩梦报告频率大于一次的为5.6%,与过往研究中对经常性噩梦发生率的结果相符(Levin, 1994; Schredl, 2010)。说明匹兹堡睡眠量表这一项对噩梦调查的问题也能很好的体现不同人群在噩梦发生率上的分布。同时我们发现了在969人大样本中的性别差异,女性比男性在统计上会报告更多得噩梦,平均每年多报告3个噩梦。注意的是,因为我们采用的是回顾式的数据收集方式,其数值仅是参考,与真实的噩梦频率存在误差(Robert & Zadra, 2008),每年多出3个噩梦对应的估计情况对应着预测女性一年内会比男性多产生6个噩梦,而其在睡眠中的情绪调节功能上的潜在性别差异,可能更加超出我们的想象(Nagy et al., 2015; Schredl & Reinhard, 2011)。同时我们也发现了不同年龄段上的噩梦频率的差异。差异主要存在于年轻人(22~25岁)和成年人(26~35岁)的人群之间,按照上述的估计方法,平均每年年轻人能比31~35岁的人群多15个噩梦。因为36岁以上的样本只有7人,未能体现足够的代表性,但是总的噩梦频率减少的趋势很明显。36岁以上人群在噩梦均数上最少,仅为年轻人组的60%,与以往研究基本吻合(Nielsen et al., 2006)。同时也证明了我们以人口学变量作为匹配被试的必要性。

4.2. 生活中压力感及心理健康与噩梦频率的关系

从表6的结果中,我们可以得知压力感作为一种情感负荷确实在噩梦达到每周三次的人群中格外突出,与其他几组存在显著差异。这个结果不仅支持了Levin的理论模型(Levin & Nielsen, 2007)中情感负荷概念的存在,更给我们以启示,似乎当噩梦数每周大于三次时(可作为新的定性指标),个体需要注意应对自己累计的情感负荷和生活压力,因为压力是一种状态因素,噩梦可能是响应式地阶段性频发。个体若主动积极地解决问题或寻求帮助,能避免噩梦不断产生的恶性循环。噩梦的高发与许多心理疾病紧密联系,但是在正常人群中噩梦是否也能体现出其对心理健康的量的影响,过往研究中往往在单一指标上给予回答,而我们的研究结果表明噩梦次数每周达到三次或以上将会全面而深刻地影响包括正性的幸福感体验以及负性情绪的累积。

4.3. 负性情绪在心理健康概念中对噩梦频率的变化更为敏感

在两类与心理健康相关的指标中,我们发现负性情绪比主观幸福感对噩梦频率的变化有更好的敏感性,首先如表6所示,在幸福感中存在像正向情绪这样的子维度,其在不同噩梦频率上差异不显著,而负性情绪中三个子维度体现出差异;同时在表7中我们可以看到,负性情绪的差异不仅体现在极端的每周三次以上组上,同时也能敏感地体现在噩梦频率为每周一次或两次组与其他组之间;在回归分析中噩梦频率能单独解释负性情绪27.4%的变异,而对主观幸福感只能解释其17.9%的变异。更重要的是,负性情绪能符合情感网络失调模型中存在调节变量的假设,而主观幸福感在回归分析中无法得到类似结果。确实过去的研究中,关于选用主观幸福感(Blagrove et al., 2004; Pesant & Zadra, 2006; Zadra & Donderi, 2000)还是负性情绪(Antunes-Alves & De Koninck, 2012; Levin & Fireman, 2002; Miró & Martínez, 2005)作为预测变量不同的实验团队各自为营,虽然大体上得到了相似的结果,但是通过我们的对比研究可以得出,噩梦在正常人群中对心理健康的影响首先作用于介观尺度的负性情绪,可能之后藉此再对更加宏观正面的主观幸福感产生影响。

4.4. 神经质调节噩梦频率对负性情绪的影响:有效的情感困扰的指标

根据情感网络失调模型中对情感困扰的构想,对比两类调节变量负性情绪敏感性和神经质人格后,我们发现负性情感敏感性在回归分析的所有模型中都无法对心理健康相关的变量起到预测作用,同时在表8中可以看出它与其他三类关注的变量都无相关关系。尽管过去研究表明高噩梦报告率的人群同时伴随着多种行为认知任务成绩的受损(Simor, Pajkossy, Horváth, & Bódizs, 2012),但我们的研究结果指出在正常人群中,噩梦的高发与否以及是否带来相应的心理健康的损害和个体的情绪认知能力与倾向并无关系。同时相较之下,神经质的人格特质作为一个有效的调节变量,深刻地调节着从噩梦产生的负面梦境记忆到之后生活中负性情绪的积累间关系。神经质属于一种稳定的长期形成的宏观特质,无论是对主观幸福感还是负性情绪,神经质本身就能起到很强的预测作用。同时经过结构方程模型的验证性分析,我们进一步确认了情感网络失调模型中神经质人格对噩梦的调节作用,为未来该领域的研究提供了新的支持与更准确的视角。

4.5. 研究的不足与展望

首先该研究受限于极端噩梦频率组(每周大于等于三次组)的限制,筛选后的进入分析的人数较少。再者对噩梦的频率只是回顾式的间接测量,或许还存在其他中间变量的影响。获得压力感数据的方法难以直接排除有主观认知倾向成分的存在,或许神经质人格本身就能促使被试知觉到更多得压力。未来或许采用生活事件记录表和更为客观的第三者评分作为压力的指标是一种有效地解决办法。对于未来的研究展望,我们认为研究压力感与睡眠中情绪调节的个体差异会有一定意义。在个体知觉到量值相当的压力感时,有的被试能在睡眠中通过负性梦境更有效地进行调节,而导致更短暂的坏梦高发以及更少的惊醒次数,其背后的神经机制将极具临床的应用价值。同样的,关于在噩梦高发后社会支持因素是如何对其进行干预和辅助的研究也有待开展。而在人口学变量年龄上,噩梦频率的变化也十分明显,或许更长的年龄跨度和长时程的被试内追踪研究,能帮助我们更深入解释老化过程中梦境的情绪调节功能的变化机制。

5. 结论

本研究通过理论模型驱动的数据挖掘,发现压力感作为情感负荷的确与噩梦的高发关系密切;同时发现了负性情感对噩梦的频率更加敏感;神经质人格作为有效的调节变量调节着两者之间的变化关系。本研究揭示了噩梦影响心理健康的人格作用机制,可能对噩梦相关心理障碍的诊疗提供帮助。

文章引用

杨正宇. 噩梦影响心理健康:神经质的调节作用

Nightmare Impacts Mental Health: The Moderation from Neuroticism Trait[J]. 心理学进展, 2018, 08(03): 450-463. https://doi.org/10.12677/AP.2018.83055

参考文献

- 1. 杨赛花, 李晓驷(2011). 创伤与噩梦的相关研究进展. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 23(6), 360-363.

- 2. 叶碧瑜, 苗国栋, 李烜, 徐贵云(2009). 抑郁症患者睡眠障碍、梦魇与自杀倾向之间关系的研究进展. 国际精神病学杂志, 36(2), 100-102.

- 3. 朱华珍(2006). 噩梦与大学生心理健康关系的研究. 硕士论文, 上海: 华东师范大学.

- 4. Antunes-Alves, S., & De Koninck, J. (2012). Pre- and Post-Sleep Stress Levels and Negative Emotions in a Sample Dream among Frequent and Non-Frequent Nightmare Sufferers. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 14, 11-16.

- 5. Backhaus, J., Junghanns, K., Broocks, A., Riemann, D., & Hohagen, F. (2002). Test-Retest Reliability and Validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Primary Insomnia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 737-740.

- 6. Belicki, K. (1992). Nightmare Frequency versus Nightmare Distress: Relations to Psychopathology and Cognitive Style. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 592-597.

- 7. Bixler, E. O., Kales, A., Soldatos, C. R., Kales, J. D., & Healey, S. (1979). Prevalence of Sleep Disorders in the Los Angeles Metropolitan area. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136, 1257-1262.

- 8. Blagrove, M., Farmer, L., & Williams, E. (2004). The Relationship of Nightmare Frequency and Nightmare Distress to Well-Being. Journal of Sleep Research, 13, 129-136.

- 9. Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193-213.

- 10. Cartwright, R. D. (1991). Dreams That Work: The Relation of Dream Incorporation to Adaptation to Stressful Events. Dreaming, 1, 3-9.

- 11. Claridge, G., Clark, K., & Davis, C. (1997). Nightmares, Dreams, and Schizotypy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 377-386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01245.x

- 12. Dang-Vu, T. T., Desseilles, M., Petit, D., Mazza, S., Montplaisir, J., & Maquet, P. (2007). Neuroimaging in Sleep Medicine. Sleep Medicine, 8, 349-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.006

- 13. DSM-5 (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association Press.

- 14. Duke, T., & Davidson, J. (2002). Ordinary and Recurrent Dream Recall of Active, Past and Non-Recurrent Dreamers during and after Academic Stress. Dreaming, 12, 185-197. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021152411010

- 15. Gehrman, P., Matt, G. E., Turingan, M., Dinh, Q., & Ancoli-Israel, S. (2002). Towards an Understanding of Self-Reports of Sleep. Journal of Sleep Research, 11, 229-236. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00306.x

- 16. Germain, A., & Nielsen, T. A. (2003). Sleep Pathophysiology in PTSD and Idiopathic Nightmare Sufferers. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 1092-1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00071-4

- 17. Hartmann, E. (1996). Outline for a Theory on the Nature and Functions of Dreaming. Dreaming, 6, 147-170. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094452

- 18. Hartmann, E. (1998). Dreams and Nightmares: The New Theory on the Origin and Meaning of Dreams. New York: Plenum.

- 19. Hartmann, E., & Russ, D. (1979). Frequent Nightmares and the Vulnerability to Schizophrenia: The Personality of the Nightmare Sufferer. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 15, 10-12.

- 20. Hartmann, E., Elkin, R., & Garg, M. (1991). Personality and Dreaming: The Dreams of People with Very Thick or Very Thin Boundaries. Dreaming, 1, 311-324. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094342

- 21. Hobson, J. A., Pace-Schott, E. F., & Stickgold, R. (2000). Dreaming and the Brain: Toward a Cognitive Neuroscience of Conscious States. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 793-842. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00003976

- 22. Hublin, C., Kaprio, J., Partinen, M., & Koskenvuo, M. (1999). Nightmares: Familial Aggregation and Association with Psychiatric Disorders in a Nationwide Twin Cohort. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 88, 329-336. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990820)88:4<329::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-E

- 23. ICSD-3 (2014). International Classification of Sleep Disorders—3rd Edition, Diagnostic and Coding Manual. American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

- 24. Köthe, M., & Pietrowsky, R. (2001). Behavioral Effects of Nightmares and Their Correlations to Personality Patterns. Dreaming, 11, 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009468517557

- 25. Kramer, M. (1991). The Nightmare: A Failure of Dream Function. Dreaming, 1, 277-285. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094339

- 26. Kroth, J., Thompson, L., Jackson, J., Pascali, L., & Ferreira, M. (2002). Dream Characteristics of Stock Brokers after a Major Market Downturn. Psychological Reports, 90, 1097-1100. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3c.1097

- 27. Lang, P. J., Davis, M., & Öhman, A. (2000). Fear and Anxiety: Animal Models and Human Cognitive Psychophysiology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 137-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00343-8

- 28. LeDoux, J. E. (2000). Emotion Circuits in the Brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, 155-184. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155

- 29. Levin, R. (1994). Sleep and Dreaming Characteristics of Frequent Nightmare Subjects in a University Population. Dreaming, 4, 127-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094407

- 30. Levin, R. (1998). Nightmares and Schizotypy. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 61, 206-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1998.11024832

- 31. Levin, R., & Fireman, G. (2002). Nightmare Prevalence, Nightmare Distress, and Self-Reported Psychological Disturbance. Sleep, 25, 205-212.

- 32. Levin, R., & Hurvich, M. S. (1995). Nightmares and Annihilation Anxiety. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 12, 247-258. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079625

- 33. Levin, R., & Nielsen, T. (2009). Nightmares, Bad Dreams and Emotion Dysregulation. A Review and New Neurocognitive Model of Dreaming. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 84-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01614.x

- 34. Levin, R., & Nielsen, T. A. (2007). Disturbed Dreaming, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Affect Distress: A Review and Neurocognitive Model. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 482-528. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.482

- 35. Mindell, J. A., & Barrett, K. M. (2002). Nightmares and Anxiety in Elementary-Aged Children: Is There a Relationship? Child: Care, Health and Development, 28, 317-322.

- 36. Miró, E., & Martínez, M. P. (2005). Affective and Personality Characteristics in Function of Nightmare Prevalence, Nightmare Distress, and Interference Due to Nightmares. Dreaming, 15, 89-105. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0797.15.2.89

- 37. Nadorff, M. R., Nazem, S., & Fiske, A. (2011). Insomnia Symptoms, Nightmares, and Suicidal Ideation in a College Student Sample. Sleep, 34, 93-98. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.1.93

- 38. Nagy, T., Salavecz, G., Simor, P., Purebl, G., Bódizs, R., Dockray, S., & Steptoe, A. (2015). Frequent Nightmares Are Associated with Blunted Cortisol Awakening Response in Women. Physiology and Behavior, 147, 233-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.05.001

- 39. Nielsen, T. A., Laberge, L., Paquet, J., Tremblay, R. E., Vitaro, F., & Montplaisir, J. (2000). Development of Disturbing Dreams during Adolescence and Their Relation to Anxiety Symptoms. Sleep, 23, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/23.6.1

- 40. Nielsen, T. A., Stenstrom, P., & Levin, R. (2006). Nightmare Frequency as a Function of Age, Gender, and September 11, 2001: Findings from an Internet Questionnaire. Dreaming, 16, 145-158. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0797.16.3.145

- 41. Nielsen, T., & Levin, R. (2007). Nightmares: A New Neurocognitive Model. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11, 295-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.004

- 42. Ohayon, M. M., Morselli, P. L., & Guilleminault, C. (1997). Prevalence of Nightmares and Their Relationship to Psychopathology and Daytime Functioning in Insomnia Subjects. Sleep, 20, 340-348. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/20.5.340

- 43. Oudiette, D., Leu, S., Pottier, M., Buzare, M., Brion, A., & Arnulf, I. (2009). Dreamlike Mentations during Sleepwalking and Sleep Terrors in Adults. Sleep, 32, 1621-1627. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.12.1621

- 44. Pesant, N., & Zadra, A. (2006). Dream Content and Psychological Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study of the Continuity Hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 111-121. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20212

- 45. Picchioni, D., Goeltzenleucher, B., Green, D. N., Convento, M. J., Crittenden, R., Hallgren, M., & Hicks, R. A. (2002). Nightmares as a Coping Mechanism for Stress. Dreaming, 12, 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020118425588

- 46. Pietrowsky, R. K., & Köthe, M. (2003). Personal Boundaries and Nightmare Consequences. Dreaming, 13, 245-254. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:DREM.0000003146.11946.4c

- 47. Poldrack, R. A., & Gorgolewski, K. J. (2014). Making Big Data Open: Data Sharing in Neuroimaging. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 1510-1517. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3818

- 48. Revonsuo, A. (2000). The Reinterpretation of Dreams: An Evolutionary Hypothesis of the Function of Dreaming. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 877-901. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00004015

- 49. Robert, G., & Zadra, A. (2008). Measuring Nightmare and Bad Dream Frequency: Impact of Retrospective and Prospective Instruments. Journal of Sleep Research, 17, 132-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00649.x

- 50. Roberts, J., & Lennings, C. J. (2006). Personality, Psychopathology and Nightmares in Young People. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 733-744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.010

- 51. Salvio, M.-A., Wood, J. M., Schwartz, J., & Eichling, P. S. (1992). Nightmare Prevalence in the Healthy Elderly. Psychology and Aging, 7, 324-325. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.2.324

- 52. Schredl, M. (2002). Questionnaires and Diaries as Research Instruments in Dream Research: Methodological Issues. Dreaming, 12, 17-26. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013890421674

- 53. Schredl, M. (2010). Nightmare Frequency and Nightmare Topics in a Representative German Sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 260, 565-570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-010-0112-3

- 54. Schredl, M., & Reinhard, I. (2011). Gender Differences in Nightmare Frequency: A Meta-Analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15, 115-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.002

- 55. Simard, V., Nielsen, T. A., Tremblay, R. E., Boivin, M., & Montplaisir, J. Y. (2008). Longitudinal Study of Bad Dreams in Preschool-Aged Children: Prevalence, Demographic Correlates, Risk and Protective Factors. Sleep, 31, 62-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/31.1.62

- 56. Simor, P., Horvath, K., Gombos, F., Takacs, K. P., & Bodizs, R. (2012). Disturbed Dreaming and Sleep Quality: Altered Sleep Architecture in Subjects with Frequent Nightmares. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 262, 687-696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-012-0318-7

- 57. Simor, P., Körmendi, J., Horváth, K., Gombos, F., Ujma, P. P., & Bódizs, R. (2014). Electroencephalographic and Autonomic Alterations in Subjects with Frequent Nightmares during Pre- and Post-REM Periods. Brain and Cognition, 91, 62-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.08.004

- 58. Simor, P., Pajkossy, P., Horváth, K., & Bódizs, R. (2012). Impaired Executive Functions in Subjects with Frequent Nightmares as Reflected by Performance in Different Neuropsychological Tasks. Brain and Cognition, 78, 274-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2012.01.006

- 59. Sjöström, N., Hetta, J., & Waern, M. (2009). Persistent Nightmares Are Associated with Repeat Suicide Attempt: A Prospective Study. Psychiatry Research, 170, 208-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.09.006

- 60. Sjöström, N., Wærn, M., & Hetta, J. (2007). Nightmares and Sleep Disturbances in Relation to Suicidality in Suicide Attempters. Sleep, 30, 91-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.1.91

- 61. Spoormaker, V. I., Schredl, M., & van den Bout, J. (2006). Nightmares: From Anxiety Symptom to Sleep Disorder. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10, 19-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2005.06.001

- 62. Tanskanen, A., Tuomilehto, J., Viinamäki, H., Vartiainen, E., Lehtonen, J., & Puska, P. (2001). Nightmares as Predictors of Suicide. Sleep, 24, 844-847.

- 63. Watson, D. (2001). Dissociations of the Night: Individual Differences in Sleep-Related Experiences and Their Relation to Dissociation and Schizotypy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 526-535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.526

- 64. Watson, D., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1989). Health Complaints, Stress, and Distress: Exploring the Central Role of Negative Affectivity. Psychological Review, 96, 234-254. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.234

- 65. Wolfson, A. R., Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., Seifer, R., Fallone, G., Labyak, S. E., & Martin, J. L. (2003). Evidence for the Validity of a Sleep Habits Survey for Adolescents. Sleep, 26, 213-216. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/26.2.213

- 66. Wood, J. M., & Bootzin, R. R. (1990). The Prevalence of Nightmares and Their Independence from Anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 64-68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.99.1.64

- 67. Wood, J. M., Bootzin, R. R., Rosenhan, D. et al. (1992). Effects of the 1989 San Francisco Earthquake on Frequency and Content of Nightmares. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101, 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.2.219

- 68. Woodward, S. H., Arsenault, N. J., Murray, C., & Bliwise, D. L. (2000). Laboratory Sleep Correlates of Nightmare Complaint in PTSD Inpatients. Biological Psychiatry, 48, 1081-1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00917-3

- 69. Zadra, A. L., Assaad, J.-M., Nielsen, T. A., & Donderi, D. C. (1995). Trait Anxiety and Its Relation to Nightmares, Bad Dreams and Dream Content. Sleep Research, 24, 150.

- 70. Zadra, A. L., Donderi, D. C., & Assaad, J.-M. (1991). Trait Anxiety and Its Relation to Bad Dreams, Nightmares, and Dream Anxiety. In 8th Annual International Conference of the Association for the Study of Dreams, Charlottesville, VA.

- 71. Zadra, A., & Donderi, D. C. (2000). Nightmares and Bad Dreams: Their Prevalence and Relationship to Well-Being. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 273-281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.273

- 72. Zadra, A., Pilon, M., & Donderi, D. C. (2006). Variety and Intensity of Emotions in Nightmares and Bad Dreams. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 249-254. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000207359.46223.dc