Advances in Psychology

Vol.07 No.08(2017), Article ID:21591,10

pages

10.12677/AP.2017.78122

The Research Progress on the Heterogeneity of Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder

Jinling Li, Haiyun Xu*

*通讯作者。

The Mental Health Center, Shantou University Medical College, Shantou Guangdong

Received: Jul. 10th, 2017; accepted: Jul. 26th, 2017; published: Aug. 3rd, 2017

ABSTRACT

Bipolar disorder (BD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are two common mood disorders with significant impacts on human health and heavy economic burdens on governments and patients’ families. In clinical practice, it is very difficult to distinguish BD from MDD as the BD patients in depressive episode stage may manifest the same symptoms as those of MDD patients. There is increasing research evidence, however, showing the differences between MDD and BD in multiple aspects, such as clinical characteristics and pathogenesis. Here, we summarized the research progress on the heterogeneity of BD and MDD by reviewing Chinese and English literature published in recent years. The main content includes the differences between the both disorders in clinical manifestations, psychological characteristics, genetic factors, neuropathology, and neurochemical metabolism. These data would be useful for the early identification of BD from MDD.

Keywords:Bipolar Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Heterogeneity, Diagnosis

双相障碍和重性抑郁障碍疾病异质性研究进展

李金灵,许海云*

汕头大学医学院精神卫生中心,广东 汕头

收稿日期:2017年7月10日;录用日期:2017年7月26日;发布日期:2017年8月3日

摘 要

双相障碍和重性抑郁障碍是两种常见的情感障碍疾病,它们不仅严重影响病人的健康,也给患者家庭和政府造成极大的经济负担。在临床实践中,很难鉴别诊断该两种疾病,因为它们有相似的临床表现,特别是抑郁发作期的双相障碍病人可能和重性抑郁障碍患者临床表现相同。所幸,有不断增加的研究证据提示,重性抑郁障碍和双相障碍两种疾病在发病机制、疾病特点等多个方面存在不同。本文总结了近年来关于双相障碍和重性抑郁障碍疾病异质性的研究进展,主要内容包括两种疾病在临床特点、心理学特征、遗传因素、神经病理学、神经生化代谢等方面的差异。了解这些新进展有助于我们在早期鉴别诊断双相障碍和重性抑郁障碍。

关键词 :双相障碍,重性抑郁障碍,异质性,诊断

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

情感障碍是指以情绪状态明显改变为主要临床特征的疾病,其中以双相情感障碍(Bipolar Disorder, BD)和重性抑郁障碍(Major Depression Disorder, MDD)两种疾病最为常见。2010年针对精神疾病的全球疾病负担统计结果显示MDD占精神疾病全球疾病负担的40.5%,BD占7.0% (Whiteford et al., 2013)。该统计结果表明,情感障碍疾病的全球疾病负担排在所有精神障碍的首位,因此对情感障碍疾病的研究是关系到提升人类健康水平、降低精神障碍全球疾病负担的重要课题。

在临床实践中,MDD与单相抑郁障碍(Unipolar Depression, UD)通用。当我们使用UD时,意在强调UD和BD的不同。有越来越多的研究证据表明,BD和UD是两种不同的情感障碍疾病(陈美英,张斌,2014),但在临床工作中不易鉴别。对既往出现过躁狂或者轻躁狂发作的患者,若继发抑郁症状则不难诊断为BD。但以抑郁症状首发的BD患者可能表现出与MDD同样的临床症状,如情绪低落、思维迟缓、兴趣缺失、活动减少等,致使临床工作中两种疾病在发病初期难以鉴别。一项关于BD误诊率的研究显示,约有20.8%的BD患者被误诊为UD,因而给予不恰当的治疗(Hu et al., 2012)。另一项研究显示,BD患者从首次出现临床症状到做出正确的临床诊断一般需要经历5~10年的时间(Baldessarini et al., 2007)。因此,BD和UD的早期鉴别十分重要。本文复习了近年来关于BD和UD异质性研究的部分文献,内容包括两种疾病在临床特点、心理学特征、遗传因素、神经病理、神经生化等方面的差异,期望帮助BD和UD的早期鉴别诊断。

2. 双相障碍和单相抑郁障碍患者的临床特点不同

有越来越多的研究证据表明,BD和UD是两种不同的情感障碍疾病。首先,它们有不同的临床特点。BD是指周期性的情绪、思维及活动的异常升高或降低,呈反复发作的特点,常伴随精神病性症状,其严重程度、持续时间及发生频率多样,发病期严重影响患者社会功能。BD的终生患病风险在1%~2%左右(Merikangas et al., 2011; Squarcina et al., 2016),并且男女患者发病风险相近,约90%患者在一生中会经历再次发作,其中9%~15%的患者可能会出现自杀行为(Medici et al., 2015)。UD是指以持续2周以上的情绪低落或兴趣减退、快感缺失为主要临床特征的情感障碍疾病,具有反复发作的特点,并且在疾病过程中从未出现过躁狂或轻躁狂状态。UD的患病率约为10%~15% (Lopizzo et al., 2015),远高于BD的患病率,而且有明显的性别差异,女性患病风险明显高于男性。近来的研究发现,约有60%~80%的患者在首次UD发作后会经历再次发作(喻东山,2003; Pettit et al., 2006)。最近的研究结果显示,BD患者的自杀风险高于UD患者(Holma et al., 2014)。

一般地,BD患者的起病年龄多在20岁以前,而UD患者的发病年龄相对较晚,部分UD患者可在40岁以后首次发病(Benazzi & Akiskal, 2008)。Angst等人(2005)的研究表明,发病年龄早、存在BD家族史、抑郁发作次数频繁的抑郁障碍患者以后发展成BD的可能性较大。Lee等(2014)的研究结果显示,与UD患者相比,BD患者表现出抑郁发作次数频繁、疾病发生更早的临床特点。Benazzi等(2008)指出疾病发生早这一临床指标在BD早期识别中的可靠性要高于伴有精神病性症状、发作次数频繁等其他临床指标。虽然如此,仅凭临床表现和相关特征很难在疾病的早期鉴别BD和UD。实际上,到目前为止尚不存在一个通用的、客观和可量化的临床评价标准用于BD和UD的鉴别诊断。

3. 双相障碍和单相抑郁障碍患者的心理学特征不同

情感障碍疾病的发生存在人格易感性。越来越多的研究表明,不同类型的情感障碍患者在人格特质方面存在差异(Akiskal et al., 2006)。Savitz (2008)等运用家族遗传关联分析的方法发现BD患者表现出的十多种人格特质与遗传相关联,推测某些人格特质可能是BD潜在的内表型。一项国内对BD患者人格特质的研究结果显示,BD患者表现出外向、开放、情绪不稳定的特点(任孝鹏,戴晓阳,2001)。Strong (2007)等对稳定期BD患者人格特质的研究,发现BD患者在开放性、神经质维度的得分明显高于正常人群,但是不同亚型BD患者的人格特质却无明显差异。Loftus (2008)等应用气质性格量表(TCI),结果提示BD患者具有高回避伤害性、高自我超越性、低自我定向性的人格特点。对UD患者人格特质的研究也发现UD患者表现出一定的人格特质倾向性。沈宗霖(2016)等研究表明,抑郁症患者表现出高神经质的人格特质。Smith (2005)等研究发现,疾病稳定期UD患者表现出高回避伤害性、低自我定向性的人格特点。Smillie (2009)等研究发现UD患者表现出高神经质、低外向性的人格特点。Fletcher (2012)等将BD不同亚型患者与UD患者的人格特质进行比较,发现BDII型患者与UD患者相比表现出冲动、焦虑、自我要求高、外向开放的人格特点,但BD不同亚型患者的人格特质差异不明显。另外一项研究同样表明,BD II型和UD患者的人格特质存在差异(Bensaeed et al., 2014)。

简言之,从心理学特征来看,BD和UD患者表现出不同的人格特质倾向,因此人格特质可以作为情感障碍疾病的易感性指标之一,帮助疾病的早期识别及诊断。随着数据的不断积累,可以期望在不久的将来推出一套或多套综合患者临床表现特点和心理学特征的诊断标准用于BD和UD的早期诊断和鉴别诊断。

4. 双相障碍和单相抑郁障碍患者的遗传因素差异

遗传因素和BD的发生关系密切。McGuffin (2003)等研究发现,BD的遗传风险约为89%。多个证据表明BD受多个基因的影响,属于多基因遗传。Sklar (2011)等对7481名BD患者运用全基因组关联研究方法进行分析,发现CACNA1C和ODZ4基因与BD的发生相关联。Baum (2008)等研究发现,DGKH是BD疾病发生的易感基因。另有学者报道,BD和其他精神障碍如精神分裂症、抑郁障碍、自闭症等,在遗传学上有着共同的易感基因,尤其与精神分裂症的易感基因重叠现象最为明显(Lee et al., 2013; Forstner et al., 2017)。

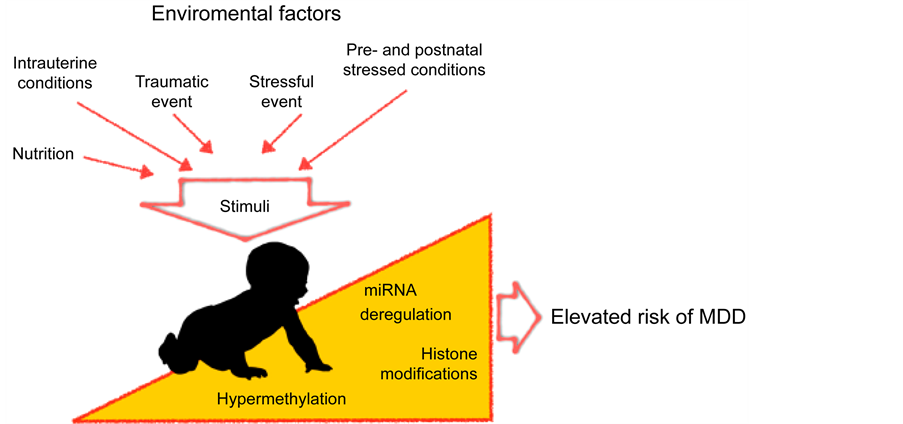

UD的发生也受遗传因素的影响。Sullivan (2000)等对UD遗传风险做的一项荟萃分析,结果显示该病遗传风险在37%左右。在过去20多年,众多研究试图通过全基因组关联研究寻找抑郁障碍的易感基因,但是研究结果缺乏一致性,重复性差,因此针对UD易感基因的研究目前不能很好的阐释抑郁障碍的发生机制。已有的共识是,UD的发生受遗传和环境因素的共同作用,并且后者在UD的发生风险中发挥更大的作用,约为63% (Sullivan et al., 2000)。表观遗传学研究证据表明,将遗传和环境因素结合起来解释抑郁障碍的发病机制更加可靠,是目前探索UD发生机制的重要方向。表观遗传学是指不涉及DNA序列改变,只聚焦于基因或者蛋白表达的变化,并且这些变化可以在发育和细胞增殖过程中稳定传递。环境因素导致的表观遗传学改变主要包括DNA甲基化,组蛋白共价修饰,染色质重塑,基因沉默和RNA编辑等,其中DNA甲基化最容易受环境因素影响,这一表观遗传机制的研究目前最受关注。研究表明表观遗传机制在UD的发生中发挥着重要作用(Urdinguio et al., 2009)。人们相信,在个体成长过程中来自外界的各种应激因素通过改变表观遗传学机制,可能导致UD的发生(图1) (Saavedra et al., 2016)。

总之,BD和UD在病因学上均受遗传和环境因素的共同影响,但BD的发生和遗传因素关系更为密切,而环境因素在UD的发生中作用更显著。

5. 双相障碍和单相抑郁障碍患者的神经影像学差异

随着医学影像学技术在情感障碍疾病研究中的应用,人们已经确证情感障碍患者存在神经病理及脑功能的改变,而且BD患者和UD患者存在神经影像学差异(Brambilla et al., 2004; Lawrence et al., 2004)。两者在神经影像学方面的差异有助于疾病的早期识别。

UD患者多伴有海马体积的变化。较早的一项研究显示,UD患者海马体积缩小(Campbell et al., 2004)。后来,Koolschijn (2009)等的一项荟萃分析发现,UD患者在前额叶皮质、扣带回、海马、纹状体等部位的体积与正常人群相比存在不同程度的缩小,但其全脑、杏仁核、丘脑、颞叶皮质等部位的体积与正常人群相比无明显差异。另一项荟萃分析结果显示,UD患者存在海马、前额叶皮质、基底核多个部位体积缩小,而且杏仁核体积变化和UD病程的长短有关,在疾病早期阶段杏仁核体积增加,但随着疾病时间的延长,杏仁核体积逐渐减小,并且女性患者杏仁核体积变化更为明显(Lorenzetti et al., 2009)。这种脑结构

Figure 1. Environmental factors, via epigenomic mechanisms, involve in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder. The schematic diagram was cited from Saavedra et al. (2016)

图1. 环境因素通过表观遗传学机制在抑郁障碍发生中的作用。引自Saavedra et al. (2016)

体积变化与病程的关系在近来的一项研究中得到进一步的验证。Bora (2012)等发现,UD患者有明显的扣带回、前额叶皮质体积缩小,杏仁核和海马的体积变化与病程长短有关。首次抑郁发作患者存在杏仁核、海马旁回体积缩小,但反复抑郁发作患者的杏仁核、海马旁回体积改变不明显。最近的无创性功能磁共振成像术(fMRI)研究发现,抑郁状态患者皮质和杏仁核连接通路功能降低(Scheuer et al., 2017)。

与UD患者不同,BD患者杏仁核的体积变化不明显(Hajek et al., 2008)。有趣的是,BD患者胼胝体体积明显缩小,并且伴有结构异常,而UD患者该部位体积改变不明显(Brambilla et al., 2004)。胼胝体是连接左右大脑半球的重要结构,该部位的损伤可能会引起认知、情绪失调等一系列问题。事实上,与同年龄正常人群相比,青少年BD患者脑白质的MRI信号强度增高,表明BD患者存在脑白质连接异常(Pillai,2002)。更有意义的是,BD患者在面对恐惧、悲伤等情绪事件时伴随有前额叶皮质及皮质下结构功能活动增加,而正常人群及UD患者则表现出功能活动降低(Lawrence, 2004)。最近的一项静息态功能连接研究显示,BD患者和UD患者脑区间的功能连接存在差异(Ambrosi et al., 2017)。

MRI和fMRI(包括静息态功能连接)均是无创性影像学技术,前者对脑组织有较好的空间分辨率,后者还具有时间分辨率高的特点。近年来由前者发展而来的弥散张量成像(DTI)术能够检测出微小的脑白质病变。随着这些新技术在精神疾病的诊断和研究工作中的广泛应用,一定会揭示BD和UD患者在神经病理学和脑功能活动方面更多的差异,最终极有可能确定一些鉴别诊断BD和UD的金标准。

6. 双相障碍和单相抑郁障碍患者神经生化的差异

BD和UD两种疾病在神经代谢方面也存在不同。Frey (2007)等利用磁共振波谱(MRS)技术,发现BD患者神经元内线粒体能量代谢水平下降。另外,Cataldo (2010)等发现BD患者前额叶皮质的线粒体存在明显的形态学改变。线粒体是细胞重要的能量供应器,其功能损害通常伴有细胞氧化磷酸化水平和钙离子信号通路的改变,这些机制在BD的发生发展中起重要作用(Kato, 2016; Scaini et al., 2016)。线粒体功能异常可带来细胞的氧化应激损伤和炎症反应增强(St-Pierre et al., 2002)。氧化应激进一步导致脂质过氧化、DNA/RNA损伤和一氧化氮水平升高,从而对神经元造成损伤。但是关于UD患者是否伴有线粒体损伤,目前缺乏一致的观点。

谷氨酸(Glutamate)和γ-氨基丁酸(GABA)是参与情感障碍疾病发生发展的重要神经递质。前者是脑内主要的兴奋性神经递质,后者是抑制性神经递质,两者在脑内分布广泛。研究表明,情感障碍患者存在谷氨酸代谢途径的异常,BD患者和UD患者在前额叶皮质都伴有谷氨酸水平升高(Hashimoto et al., 2007)。谷氨酸浓度升高可产生神经兴奋毒性或引起神经细胞死亡。Sanacora (2004)等研究表明UD患者在皮质部位不仅伴有GABA和谷氨酸代谢异常,而且不同亚型的抑郁障碍患者GABA水平存在差异,因此该文提出GABA有可能成为UD亚型区分的生物学指标。一项对重性精神障碍患者脑内GABA含量变化的荟萃分析结果显示,抑郁障碍患者脑内GABA含量明显降低,但是BD患者和精神分裂症患者脑内GABA变化不明显(Schür et al., 2016)。

已经知道,中枢神经系统的五羟色胺(5-HT)能神经元在认知、情绪控制等方面发挥重要作用。5-HT能神经元功能异常和UD的发生关系密切,在临床实践中通常应用阻断5-HT再摄取的抗抑郁药物增加突触间隙的5-HT含量,因而改善患者的抑郁症状。5-HT转运体(5-HTT)是对5-HT有高度亲和力的跨膜转运蛋白,位于突触前膜,其功能主要是再摄取突触间隙的5-HT。动物实验研究表明,脑内5-HTT功能受损会产生抑郁样行为(Line et al., 2014)。在人类研究中发现,UD患者存在5-HTT蛋白表达水平降低,尤其是在杏仁核、中脑部位降低明显(Arango et al., 2001)。虽然5-HTT功能异常在BD患者也有报道,但在UD患者中更为常见,并且对UD的发生影响更加显著(Kuzelova et al., 2010)。突触后膜5-HT受体数量和结合力降低也与情感障碍的发生相关。动物实验表明,5-HT 1A受体基因敲除的小鼠表现抑郁焦虑样行为(Domínguez-López et al., 2012), 5-HT 3A和5-HT 3B受体基因的异常和BD的发生相关联(Hammer et al., 2012; Jian et al., 2016)。

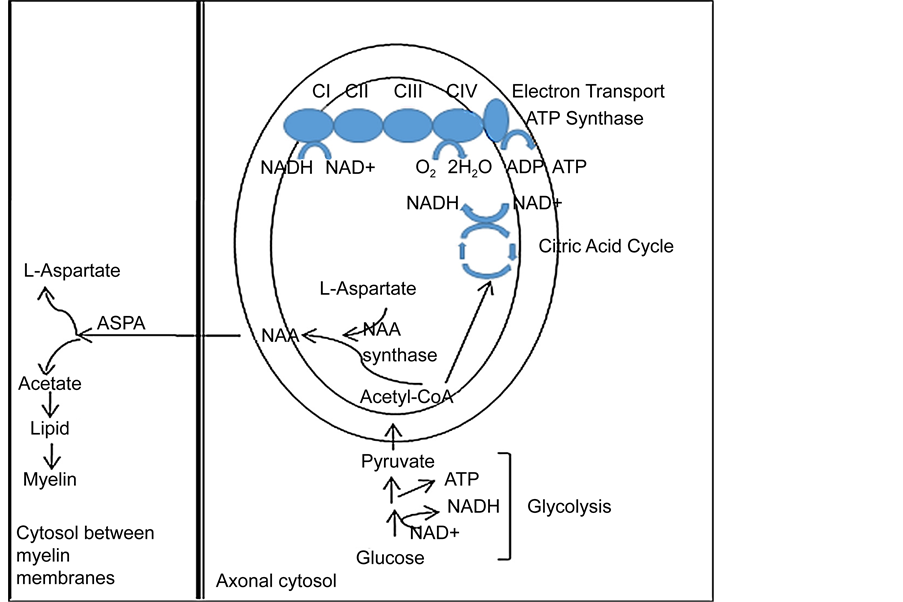

与MRI及fMRI技术相比,MRS技术存在空间分辨率较低的缺点。但是,它无可比拟的优点是能够在活体无创性地检测出多达20种以上的脑代谢物水平,包括glutamate, glutamine, GABA, 和NAA(N-乙酰门冬氨酸)等。在很长的一段时间内,临床精神病学家对这些脑代谢物变化的神经生物学机制缺乏深入的理解,因而各自对研究结果的解释不一致,甚至相互矛盾。最近,该文的作者(许海云教授)基于其团队近年来的实验研究结果(Shao et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016),结合基础神经生物学的研究进展,发展了神经元–神经胶质整合的概念,并明确提出glutamate-glutamine循环是神经元–星型胶质细胞功能整合的神经化学基质(neurochemical substrate)。Glutamate在神经元内合成,释放至突触间隙并作用于突触后膜上相应的受体。在下一个神经冲动到来之前,突触间隙内的glutamate必须及时清除,其中部分glutamate被突触间隙附近的星型胶质细胞摄取。在星型胶质细胞内,glutamate被及时转变为glutamine,后者被释放并进入谷氨酸能神经元内,成为glutamate的前体(图2)。所以,glutamate和glutamine的水平及二者的比例反映了神经元–星型胶质细胞功能整合的状态。作者还提出,NAA是神经元–少突胶质细胞功能整合的生物标志物。NAA在神经元的线粒体内合成,被送至少突胶质细胞内并被分解,其分解产物(乙酸)被用作合成脂质和髓鞘的材料(图3)。所以,NAA水平过高和过低均标志着神经元–少突胶质细胞功能整合的

Figure 2. Glutamate-glutamine cycle. Figure was reproduced from Schousboe et al., 2013

图2. 谷氨酸–谷氨酰胺循环

Figure 3. NAA involves in myelination and axon-glial signaling. Figure was reproduced from Xu et al., 2016

图 3. NAA参与髓鞘形成和神经元–少突胶质通讯

损害。按照上述理论,神经元–神经胶质细胞功能整合的损害是许多精神疾病包括BD和UD的神经生物学根本机制。当然,不同的精神疾病表现出各自不同的损害特征(Xu et al., 2016)。在BD患者,其前扣带回(ACC)的glutamate和glutamine水平均升高,提示神经元–星型胶质细胞功能整合障碍,谷氨酸能神经元功能亢进。其额叶和海马脑区的NAA水平降低,提示此两脑区神经元–少突胶质细胞功能整合障碍,神经元活性降低。在MDD患者,其前额叶(PFC)的glutamate和glutamine水平均降低,提示神经元–星型胶质细胞功能整合障碍,谷氨酸能神经元功能低下。其前额叶和额叶脑白质的NAA水平降低,提示此两脑区神经元–少突胶质细胞功能整合障碍,神经元活性降低。

7. 展望

综上所述,BD和UD在病因学、发病机制、疾病特点等多个方面存在差异,认识和重视这些差异有助于BD和UD的早期识别,从而减少两种疾病的误诊和漏诊,为疾病的正确诊断提供理论依据。但是,目前此两种情感障碍的病因仍不清楚,临床工作中对它们的诊断仍然是主观诊断,缺乏明确的客观实验室依据。随着神经科学在基础研究领域的进展和新的研究技术和检查手段,特别是无创性神经影像学技术在临床研究和诊断中的应用,可以期望,在不久的未来我们将能够借助一些较客观的实验室指标和无创性检查技术对BD和UD进行诊断和鉴别诊断。

文章引用

李金灵,许海云. 双相障碍和重性抑郁障碍疾病异质性研究进展

The Research Progress on the Heterogeneity of Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder[J]. 心理学进展, 2017, 07(08): 978-987. http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/AP.2017.78122

参考文献 (References)

- 1. 陈美英, 张斌(2014). 《精神障碍诊断与统计手册第五版》双相障碍分类和诊断标准的循证依据. 中华脑科疾病与康复杂志(电子版), 4, 207-211.

- 2. 任孝鹏, 戴晓阳(2001). 双相情感障碍患者人格特征的初步研究. 中国临床心理学杂志, 9(1), 52-53.

- 3. 沈宗霖, 程宇琪, 刘晓妍, 杨舒然, 叶靖, 许秀峰(2016). 首发未用药抑郁症患者大五人格特征对照研究. 中国神经精神疾病杂志, 7, 415-419.

- 4. 喻东山(2003). 单相抑郁症复发率的动态分析. 中国心理卫生杂志, 17(3), 208-208.

- 5. Akiskal, H. S., Kilzieh, N., Maser, J. D. et al. (2006). The Distinct Temperament Profiles of Bipolar I, Bipolar II and Unipolar Patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 92, 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.033

- 6. Ambrosi, E., Arciniegas, D. B., Madan, A. et al. (2017). Insula and Amygdala Resting-State Functional Connectivity Differentiate Bipolar from Unipolar Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 136, 129-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12724

- 7. Angst, J., Sellaro, R., Stassen, H. H., & Gamma, A. (2005). Diagnostic Conversion from Depression to Bipolar Disorders: Results of a Long-Term Prospective Study of Hospital Admissions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 84, 149-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00195-2

- 8. Arango, V., Underwood, M. D., Boldrini, M. et al. (2001). Serotonin 1A Receptors, Serotonin Transporter Binding and Serotonin Transporter MRNA Expression in the Brainstem of Depressed Suicide Victims. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25, 892-903. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00310-4

- 9. Baldessarini, R. J., Tondo, L., Baethge, C. J. et al. (2007). Effects of Treatment Latency on Response to Maintenance Treatment in Manic-Depressive Disorders. Bipolar Disord, 9, 386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00385.x

- 10. Baum, A. E., Akula, N., Cabanero, M. et al. (2008). A Genome-Wide Association Study Implicates Diacylglycerol Kinase Eta (DGKH) and Several Other Genes in the Etiology of Bipolar Disorder. Molecular Psychiatry, 13, 197-207. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002012

- 11. Benazzi, F., & Akiskal, H. S. (2008). How Best to Identify a Bipolar-Related Subtype among Major Depressive Patients without Spontaneous Hypomania: Superiority of Age at Onset Criterion over Recurrence and Polarity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107, 77-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.032

- 12. Bensaeed, S., Ghanbari, J. A., Jomehri, F., & Moradi, A. (2014). Comparison of Temperament and Character in Major Depressive Disorder versus Bipolar II Disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 8, 28-32.

- 13. Bora, E., Fornito, A., Pantelis, C., & Yücel, M. (2012). Gray Matter Abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta- Analysis of Voxel Based Morphometry Studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 138, 9-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.049

- 14. Brambilla, P., Nicoletti, M., Sassi, R. B. et al. (2004). Corpus Callosum Signal Intensity in Patients with Bipolar and Unipolar Disorder. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 75, 221-225.

- 15. Campbell, S., Marriott, M., Nahmias, C., & MacQueen, G. M. (2004). Lower Hippocampal Volume in Patients Suffering from Depression: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 598-607. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.598

- 16. Cataldo, A. M., McPhie, D. L., Lange, N. T. et al. (2010). Abnormalities in Mitochondrial Structure in Cells from Patients with Bipolar Disorder. American Journal of Pathology, 177, 575-585. https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2010.081068

- 17. Domínguez-López, S., Howell, R., & Gobbi, G. (2012). Characterization of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Knockout Mice: Implications for Major Depression. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 23, 429-443. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2012-0044

- 18. Fletcher, K., Parker, G., Barrett, M. et al. (2012). Temperament and Personality in Bipolar II Disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136, 304-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.033

- 19. Forstner, A. J., Hecker, J., Hofmann, A. et al. (2017). Identification of Shared Risk Loci and Pathways for Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. PLoS One, 12, e0171595. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171595

- 20. Frey, B. N., Stanley, J. A., Nery, F. G. et al. (2007). Abnormal Cellular Energy and Phospholipid Metabolism in the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex of Medication-Free Individuals with Bipolar Disorder: An in Vivo 1H MRS Study. Bipolar Disorder, 9, 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00454.x

- 21. Hajek, T., Kozeny, J., Kopecek, M. et al. (2008). Reduced Subgenual Cingulate Volumes in Mood Disorders: A Meta- Analysis. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 33, 91-99.

- 22. Hammer, C., Cichon, S., Mühleisen, T. W. et al. (2012). Replication of Functional Serotonin Receptor Type 3a and B Variants in Bipolar Affective Disorder: A European Multicenter Study. Translational Psychiatry, 2, e103. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2012.30

- 23. Hashimoto, K., Sawa, A., & Iyo, M. (2007). Increased Levels of Glutamate in Brains from Patients with Mood Disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 62, 1310-1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.017

- 24. Holma, K. M., Haukka, J., Suominen, K. et al. (2014). Differences in Incidence of Suicide Attempts between Bipolar I and II Disorders and Major Depressive Disorder. Bipolar Disorder, 16, 652-661. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12195

- 25. Hu, C., Xiang, Y. T., Ungvari, G. S. et al. (2012). Undiagnosed Bipolar Disorder in Patients Treated for Major Depression in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140, 181-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.014

- 26. Jian, J., Li, C., Xu, J. et al. (2016). Associations of Serotonin Receptor Gene HTR3A, HTR3B, and HTR3A Haplotypes with Bipolar Disorder in Chinese Patients. Genetics and Molecular Research, 15, Article ID: 15038671. https://doi.org/10.4238/gmr.15038671

- 27. Kato, T. (2016). Neurobiological Basis of Bipolar Disorder: Mitochondrial Dysfunction Hypothesis and Beyond. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- 28. Koolschijn, P. C., van Haren, N. E., Lensvelt-Mulders, G. J. et al. (2009). Brain Volume Abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Human Brain Mapping, 30, 3719-3735. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20801

- 29. Kuzelova, H., Ptacek, R., & Macek, M. (2010). The Serotonin Transporter Gene (5-HTT) Variant and Psychiatric Disorders: Review of Current Literature. Neuro Endocrinology Letters, 31, 4-10.

- 30. Lawrence, N. S., Williams, A. M., Surguladze, S. et al. (2004). Subcortical and Ventral Prefrontal Cortical Neural Responses to Facial Expressions Distinguish Patients with Bipolar Disorder and Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry, 55, 578- 587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017

- 31. Lee, C. I., Jung, Y. E., Kim, M. D. et al. (2014). The Prevalence of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in Elderly Patients with Recurrent Depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 10, 791-795.

- 32. Lee, S. H., Ripke, S., Neale, B. M. et al. (2013). Genetic Relationship between Five Psychiatric Disorders Estimated from Genome-Wide SNPs. Nature Genetics, 45, 984-994. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2711

- 33. Line, S. J., Barkus, C., Rawlings, N. et al. (2014). Reduced Sensitivity to Both Positive and Negative Reinforcement in Mice Over-Expressing the 5-Hydroxytryptamine Transporter. European Journal of Neuroscience, 40, 3735-3745. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.12744

- 34. Loftus, S. T., Garno, J. L., Jaeger, J. et al. (2008). Temperament and Character Dimensions in Bipolar I Disorder: A Comparison to Healthy Controls. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42, 1131-1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.11.005

- 35. Lopizzo, N., Bocchio, C. L., Cattane, N. et al. (2015). Gene-Environment Interaction in Major Depression: Focus on Experience-Dependent Biological Systems. Front Psychiatry, 6, 68. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00068

- 36. Lorenzetti, V., Allen, N. B., Fornito, A., & Yücel, M. (2009). Structural Brain Abnormalities in Major Depressive Disorder: A Selective Review of Recent MRI Studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.021

- 37. McGuffin, P., Rijsdijk, F., Andrew, M. et al. (2003). The Heritability of Bipolar Affective Disorder and the Genetic Relationship to Unipolar Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 497-502. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497

- 38. Medici, C. R., Videbech, P., Gustafsson, L. N. et al. (2015). Mortality and Secular Trend in the Incidence of Bipolar Disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 39-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.032

- 39. Merikangas, K. R., Jin, R., He, J. P. et al. (2011). Prevalence and Correlates of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 241-251. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12

- 40. Pettit, J. W., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2006). Propagation of Major Depressive Disorder: Relationship between First Episode Symptoms and Recurrence. Psychiatry Research, 141, 271-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.022

- 41. Pillai, J. J., Friedman, L., Stuve, T. A. et al. (2002). In-creased Presence of White Matter Hyperintensities in Adolescent. Psychiatry Research, 114, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-4927(01)00129-9

- 42. Saavedra, K., Molina-Márquez, A. M., Saavedra, N. et al. (2016). Epigenetic Modifications of Major Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081279

- 43. Sanacora, G., Gueorguieva, R., Epperson, C. N. et al. (2004). Subtype-Specific Alterations of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid and Glutamate in Patients with Major Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 705-713. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705

- 44. Savitz, J., Van der Merwe, L., & Ramesar, R. (2008). Personality Endophenotypes for Bipolar Affective Disorder: A Family- Based Genetic Association Analysis. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 7, 869-876. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00426.x

- 45. Scaini, G., Rezin, G. T., Carvalho, A. F. et al. (2016). Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder: Evidence, Pathophysiology and Translational Implications. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 68, 694-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.040

- 46. Scheuer, H., Alarcón, G., Demeter, D. V. et al. (2017). Reduced Fronto-Amygdalar Connectivity in Adolescence Is Associated with Increased Depression Symptoms over Time. Psychiatry Research, 266, 35-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.05.012

- 47. Schousboe, A., Bak, L. K., & Waagepetersen, H. S. (2013). Astrocytic Control of Biosynthesis and Turnover of the Neurotransmitters Glutamate and GABA. Frontiers in Endocrinology, (Lausanne), 4, 102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2013.00102

- 48. Schür, R. R., Draisma, L. W., Wijnen, J. P. et al. (2016). Brain GABA Levels across Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of (1) H-MRS Studies. Human Brain Mapping, 37, 3337-3352. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23244

- 49. Shao, Y., Yan, G., Xuan, Y. et al. (2015). Chronic Social Isolation Decreases Glutamate and Glutamine Levels and Induces Oxidative Stress in the Rat Hippocampus. Behavioural Brain Research, 282, 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.01.005

- 50. Sklar, P., Ripke, S., Scott, L. J. et al. (2011). Large-Scale Ge-nome-Wide Association Analysis of Bipolar Disorder Identifies a New Susceptibility Locus near ODZ4. Nature Genetics, 43, 977-983. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.943

- 51. Smillie, L. D., Bhairo, Y., Gray, J. et al. (2009). Personality and the Bipolar Spectrum: Normative and Classification Data for the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50, 48-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.05.010

- 52. Smith, D. J., Duffy, L., Stewart, M. E. et al. (2005). High Harm Avoidance and Low Self-Directedness in Euthymic Young Adults with Recurrent, Early-Onset Depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87, 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.014

- 53. Squarcina, L., Fagnani, C., Bellani, M. et al. (2016). Twin Studies for the Investigation of the Relationships between Genetic Factors and Brain Abnormalities in Bipolar Disorder. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25, 515-520. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000615

- 54. St-Pierre, J., Buckingham, J. A., Roebuck, S. J. et al. (2002). Topology of Superoxide Production from Different Sites in the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277, 44784-44790. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M207217200

- 55. Strong, C. M., Nowakowska, C., Santosa, C. M. et al. (2007). Temperament-Creativity Relationships in Mood Disorder Patients, Healthy Controls and Highly Creative Individuals. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100, 41-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.015

- 56. Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic Epidemiology of Major Depression: Review and Meta- Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1552-1562. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552

- 57. Urdinguio, R. G., Sanchez-Mut, J. V., & Esteller, M. (2009). Epigenetic Mechanisms in Neurological Diseases: Genes, Syndromes, and Therapies. Lancet Neurology, 8, 1056-1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70262-5

- 58. Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J. et al. (2013). Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 382, 1575-1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

- 59. Xu, H., Zhang, H., Zhang, J. et al. (2016). Evaluation of Neuron-Glia Integrity by in Vivo Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: Implications for Psychiatric Disorders. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 563-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.027

- 60. Zhang, H., Yan, G., Xu, H. et al. (2016). The Recovery Trajectory of Adolescent Social Defeat Stress-Induced Behavioral, (1)H-MRS Metabolites and Myelin Changes in Balb/C Mice. Scientific Reports, 10, Article ID: 27906. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27906