Advances in Microbiology

Vol.

07

No.

04

(

2018

), Article ID:

27671

,

8

pages

10.12677/AMB.2018.74017

The Research Advances in the Toxin Cereulide Produced by Bacillus cereus

Lan Lin*, Xudong Xu

Department of Bioengineering, Medical School, Southeast University, Nanjing Jiangsu

Received: Nov. 2nd, 2018; accepted: Nov. 15th, 2018; published: Nov. 22nd, 2018

ABSTRACT

Bacillus cereus (Bc), as a foodborne opportunistic pathogen, can produce a kind of emetic toxin, termed cereulide, and several enterotoxins. The emetic food poisoning caused by B. cereus is common in Asian areas. Bc emetic strains (Bce) are prevalent in starchy foods and milky products, which results in a growing body of food poisoning reports in recent years; however, few control measures have been documented. This paper summarizes the recent advances concerning the mode of actions of cereulide, the distribution of Bce, the biosynthesis of cereulide and the regulation thereof, which would provide the foundation for controlling this kind of food poisoning.

Keywords:Bacillus cereus (Bc), Cereulide, Biosynthesis, Food Poisoning

蜡样芽孢杆菌毒素Cereulide的研究进展

林岚*,徐旭东

东南大学医学院生物工程系,江苏 南京

收稿日期:2018年11月2日;录用日期:2018年11月15日;发布日期:2018年11月22日

摘 要

蜡样芽孢杆菌是一种食源性条件致病菌,它能产生一种呕吐毒素cereulide和多种肠毒素;该菌引起的食物中毒在亚洲以呕吐型比较常见,致吐毒株(Bc emetic strains, Bce)在淀粉类食物和乳制品中分布较广,所致食物中毒的报道近年激增,但防治措施研究鲜有报道。通过综述蜡样芽孢杆菌毒素作用、致吐毒株的分布、cereulide生物合成与调控方面的进展,为防治该类食物中毒提供依据。

关键词 :蜡样芽孢杆菌,呕吐毒素,生物合成,食物中毒

Copyright © 2018 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 蜡样芽孢杆菌与食物中毒

蜡样芽孢杆菌(Bacillus cereus, Bc)为革兰氏阳性、产芽孢的兼性厌氧杆菌,在普通琼脂平板上菌落较大,灰白色,表面粗糙似融蜡状。该群中还有与Bc同源性高度相似的苏云金芽孢杆菌(Bacillus thuringiensis,Bt)、炭疽芽孢杆菌(Bacillus anthracis)、覃状芽孢杆菌(Bacillus mycoides)、假真菌样芽孢杆菌(Bacillus pseudomycoides)和韦氏芽孢杆菌(Bacillus weihenstephanensis)等。

该菌广泛分布于土壤、水、尘埃、可食的块茎 (如马铃薯)中,常污染淀粉类制品和乳制品,在芽孢杆菌中致病性仅次于炭疽芽孢杆菌;Bc作为一种条件致病菌,偶尔引起人的眼部感染,更常见的是引起食源性中毒 [1] [2] [3] 和菌血症、急性脑病甚至横纹肌溶解 [4] [5] 。通常中毒症状较温和而且病程不超过24 h,通常导致两种不同类型的食物中毒:腹泻型和呕吐型。

1) 呕吐型:由致吐毒株(Bcemetic strains, Bce)预产生(pre-form)呕吐毒素(cereulide)引起。该毒素耐高温、耐pH值、能抗消化酶解。进食0.5 h ~6 h后出现恶心、呕吐,严重者可出现爆发性肝衰竭而迅速死亡 [1] [6] ;目前的各种食品加工方法,包括灭菌,均无法使cereulide失活。如果摄取的食物中含cereulide,它能够保持完整并可能转化成活性毒素吸附于内脏。

2) 腹泻型:由非致吐毒株产生不耐热肠毒素引起,进食后6 h~15 h发病,持续24 h后自愈 [1] [3] 。迄今已发现至少有5种不同的肠毒素,包括2个三元毒素:溶血素HBL(hbl)、非溶血性的肠毒素Nhe(nhe);3个单一基因的产物:细胞毒素K(cytK)、肠毒素T(bceT)和肠毒素HlylI。肠毒素进入胃中会被破坏,故腹泻型食物中毒是因残留的Bc在小肠中产肠毒素引起的。引起该类中毒的食物包括肉类、海鲜、乳品和蔬菜等,欧美国家多见。主要症状是水样腹泻、腹部痉挛和疼痛,少见呕吐。一般导致中毒的食品中Bc数量在105 cfu/g ~108 cfu/g,也有在数量较低的情况下(103 cfu/g ~104 cfu/g)致病 [1] 。

该菌引起的食物中毒在亚洲以呕吐型比较常见 [3] [7] 。引起呕吐型中毒的致吐毒株多分布在淀粉类食品(炒饭、米粉或土豆泥等)以及乳制品中(表1)。章乐怡等调查了国内市售的34份婴幼儿奶粉和5份米粉,Bc检出率为71.8%,其中致吐毒株占17.9% [8] 。特别适合致吐毒株产毒的食材包括熟米饭,熟米饭于20℃ 12 h~16 h后产生呕吐毒素达0.36 μg/g,土豆泥、面条以及意大利通心粉产毒 0.08 μg/g~0.16 μg/g、紧随其后,面包、蛋糕仅产cereulide 0.02 μg/g,蛋、鱼以及肉制品可维持该菌生长但产毒不明显(<0.005 μg/g) [13] [14] 。另一项研究显,28℃ 48 h条件下,致吐毒株在土豆泥中产毒高达4.080 μg/g,在意大利面中3.30μg/g,在米饭、牛奶中分别产毒2.01 μg/g和1.14 μg/ml [13] [15] 。对于大规模食源性呕吐中毒事件的研究显示cereulide剂量为0.01 μg/g~1.28 μg/g食物,即体重约70 kg的成年人摄取100 g此类食物就可引起呕吐中毒 [12] [13] 。除了淀粉类食物之外,乳制品中检出致吐毒株的比率居高不下,比如:研究者于2014年~2015年从321份牛奶、环境样本以及蜡样芽孢杆菌益生菌产品样本中分离得到110株蜡样芽孢杆菌(分离率为34.5%),其中从1株牛奶样本中分离到的蜡样芽孢杆菌(编号CAU45)分泌cereulide能力是标准菌DSMZ4312的17倍 [17] 。过去几十年因缺乏灵敏的检测方法以及Bc所致的胃肠道症状常归因于其它食源致病菌(如金黄色葡萄球菌),蜡样芽孢杆菌致吐毒株(Bce)发生率被大大低估。近十年来随着多重PCR、荧光素酶报导菌株原位检测与质谱技术的发展,食源性致吐毒株的检出率和诊断率显著提高。自2006年以来,致吐毒株所致食物中毒的报道激增,而且还在持续升高 [9] 。最近的典型例子包括比利时一个幼儿园爆发蜡样芽孢杆菌所致食物中毒,在食物中检测到了高含量(达4.2 μg/g)的cereulide [18] 。

Table 1. Distribution of B. cereus emetic strains in food specimens

表1. 食品中蜡样芽孢杆菌致吐毒株的分布

n,样品数;nd,未统计;Bc,样品中分离到的蜡样芽孢杆菌数目;Bce %,分离到的蜡样芽孢杆菌群中致吐毒株(Bc emetic strains)百分比。

2. 蜡样芽孢杆菌致吐毒株(Bce)的分布

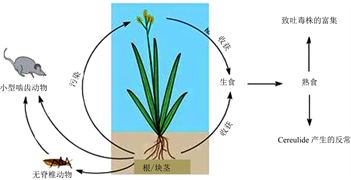

Bce在环境中分布率很低,如土壤检出率为0%~0.2%,但一些植物的根/块茎则是其最适定殖场所,Bce以共生菌或生物膜形式存在其中 [9] 。水稻根部为Bce的大本营 [10] 。植物地上部分在收获时易被含Bce的根围菌污染、或经啮齿动物污染,进而污染粮食(图1)。植物地上部分用作草料后可污染奶牛乳房,进而使Bce污染乳制品 [9] 。2013年,Bce作为共生菌在马铃薯块茎的细胞间隙中被发现,该菌对马铃薯块茎无害 [2] 。已知活植物体间质空间和维管系统是缺K的微环境 [11] 。Bce所产生的cereulide能在贫钾环境中搜寻钾,还可抗真菌以保护块茎免受病原真菌的侵袭 [11] [12] ,因此cereulide生物合成有利于Bce适应环境。

3. 呕吐毒素(cereulide)的生物合成与调控

作为蜡样芽孢杆菌致吐毒株(Bc emetic strain, Bce)的毒力因子,cereulide是一种环肽,其结构为[D-O-Leu-D-Ala-L-O-Val-L-Val]3;cereulide结构与活性上类似于已知的线粒体毒肽−−缬氨霉素,均为特异性K+载体。cereulide与K+亲和力强于缬氨霉素,故前者对哺乳动物毒性更强;cereulide通过异常升高线粒体内K+浓度而使线粒体肿胀、膜电势消失、呼吸链受抑。除了破坏线粒体功能之外,医学研究表明cereulide对人体有多种毒性,如:抑制天然杀伤细胞(natural killer cell, NK)而影响免疫力;在胃中干扰血清素(5-HT3)神经感受器的信号传入而导致肠胃炎;引起急性肝衰竭 [4] [5] 。另据比利时公共卫生中心Vangoitsenhoven教授团队的报道,cereulide在极低浓度下(~4 ng/g食物)能破坏胰岛β细胞,导致细胞凋亡和胰岛功能异常;研究人员指出长期食用污染cereulide的食品与糖尿病发生密不可分,并认为食源性cereulide可能是近年亚洲地区糖尿病发生率持续上升的元凶之一 [16] 。

Figure 1. Potential ecological niche of Bacillus cereus emetic strains (according to Ref. [9] )

图1. 蜡样芽孢杆菌致吐毒株的潜在生态位 (修改自:参考文献 [9] )

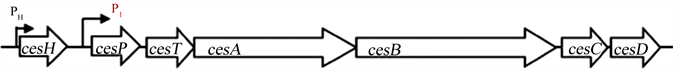

致吐毒株(Bce)中, 呕吐毒素cereulide的生物合成由ces-非核糖体肽合成酶(ces-NRPS)负责,ces基因簇(24kb)位于大型质粒pCER270上(图2),由cesH,cesP,cesT,cesA,cesB,cesC和cesD组成 [6] [9] [19] 。其中cesPTABCD组成一个操纵子(ces-operon),在主要启动子P1驱动下转录成一条23 kb多顺反子mRNA链,而相邻的cesH由自身启动子PH驱动转录成单顺反子。ces基因簇包括典型的非核糖体肽合成酶(ces-NRPS)基因,如:启动NRPS合成必需的4’-磷酸泛酰巯基乙胺基转移酶基因cesP、II型硫酯酶的编码基因cesT、负责肽链装配的酶模块基因—结构基因cesA和cesB。此外,ces基因簇还有3个ORF:位于ces基因簇5’-端的cesH基因,编码产物推定为水解酶;位于基因簇 3’-端的cesC/D 基因,产物推定为ABC转运蛋白 [6] [20] 。

Figure 2. Genetic organization of the cereulide synthetase gene cluster (Modified from Ref. [6] [20] )

图2. Cereulide生物合成基因簇的组成(修改自:参考文献 [6] [20] )

蜡样芽孢杆菌亚群(Bacillus cereus group或Bacillus cereussensulato) 包括狭义的蜡样芽孢杆菌(B. cereus sensustricto)、苏云金杆菌(B. thuringiensis)、炭疽杆菌(B. anthracis)、韦氏芽孢杆菌(B. weihenstephanensis)等,它们具有相似的生理生化特征和极高基因组同源性,主要差异在于携带不同的产毒质粒而各具致病与宿主特异性 [21] 。已发现Bce毒株大多属于狭义的蜡样芽孢杆菌,也有几株鉴定为韦氏芽孢杆菌(B. weihenstephanensis)。ces-NPRS基因簇已公认为Bce的分子标记,十年来发展起来的多重PCR检测毒素合成基因(ces A, B)转录水平的技术即基于此原理 [19] [20] 。环境中产毒质粒会自然丢失,同时也具很高的水平转移潜能 [21] [22] [23] 。2014年研究发现ces-NRPS在蜡样芽孢杆菌亚群成员——狭义的蜡样芽孢杆菌和韦氏芽孢杆菌之间有水平转移 [21] 。

呕吐毒素的生物合成受细菌内在因素与环境诸多条件的影响:1) 只有细菌密度达到一定阈值(>106 cfu/mL)时,毒素合成才启动 [12] ;2) 环境中的营养物、NaCl、温度、氧、pH和水活度等均可影响毒素的合成 [9] 。然而这些环境因子如何被致吐毒株所感知、如何调节细胞生理/代谢并作用于毒素合成通路的机制尚不清楚。

大量研究表明,ces-NRPS基因转录(即cereulide的合成)在Bce的对数生长期后期启动,进入稳定期后迅速关闭,体现出严格的时间控制,并与环境中营养物质等因素有关 [9] 。这种调控可能是由细菌的多效性转录调节子如CodY、Spo0A等来实现的。在Bce中,CodY调节染色体与质粒pCER270间的信息交流,从而将细菌的营养/能量状态与致病性紧密联系起来。当CodY辅阻遏物(支链氨基酸,GTP等)下降、但细胞饥饿状态不太严重、且产孢通路已启动时,ces-NRPS才启始表达。当细菌感知氨基酸缺乏,则进入分岔途径——细胞分化:大幅度下调分泌型蛋白(如:不耐热肠毒素)的产生而转向到cereulide的生物合成通路 [9] 。Spo0A不仅调控产孢而且调控生物膜形成以及呕吐毒素的合成启始。Spo0A主要经由跨膜蛋白KinC/D (histidine kinase C/D,组氨酸激酶C/D)引起Spo0A磷酸化(Spo0A~P),进而下调转录阻遏子AbrB和SinR,而SinR的去阻遏则导致生物膜形成中胞外基质合成相关基因的激活,故Spo0A磷酸化(Spo0A~P)能触发生物膜形成,是细菌迅速应对环境中竞争菌的一种群体感应(quorum-sensing, QS)机制 [24] [25] 。同时,Spo0A的磷酸化也能通过AbrB的去阻遏而启动cereulide合成 [9] 。

另一个可能的调控机制是LuxS QS (群体感应)系统。LuxS QS广泛存在于G+和G-细菌中,LuxS蛋白作为自诱导剂-2 (Autoinducer-2, AI-2)合成酶,是LuxS QS系统的必需元件。AI-2调节依赖于细胞密度的细菌种内/种间通信,参与到细菌致病性、毒素产生、生物膜形成以及生物发光等次生代谢的调控中 [24] 。在混杂的微生物群体中,AI-2能感知它种菌的细胞密度、进而决定是否启动有利自身生存的策略,比如细菌素的合成。蜡样芽孢杆菌具有AI-2介导的LuxS QS信号通路 [24] [26] [27] ,而且呕吐毒素cereulide能抑制其它蜡样芽孢杆菌但不抑制致吐毒株,可视为细菌素 [12] 。Qian等研究表明, 碱性环境中蜡样芽孢杆菌AI-2的产生依赖于细菌生长周期:在对数期晚期达最高,稳定期初期开始下降 [26] ,此与cereulide生物合成的动态特征相一致。迄今研究表明,蜡样芽孢杆菌生物膜受Spo0A调节机制与同属的枯草芽孢杆菌 (模式微生物) 高度类似,均由QS调控 [24] 。2016年Duanis-Assaf等揭示,枯草芽孢杆菌生物膜形成受AI-2介导的LuxS QS调控,乳糖可促进AI-2产生而参与调控生物膜形成 [24] 。这与以往报道的葡萄糖刺激细菌AI-2合成 [28] 、葡萄糖对呕吐毒素的合成有刺激效应 [29] 相似。

Lücking等报道cesH基因编码的CesH蛋白也能抑制呕吐毒素的合成:cesH插入失活突变后比野生型产毒更多,而在致吐毒株F4810/72 (致吐毒株的参考菌株)中过表达CesH则丧失产毒表型,cesA、B的转录水平大幅下调 [6] 。作者认为cesH是关闭mRNA合成的一个“切断”信号,但其具体的分子机制有待进一步研究。

4. 蜡样芽孢杆菌的抗生素耐药性

蜡状芽孢杆菌对抗生素表现出抗性。最熟知的抗性是针对β-内酰胺类抗生素比如青霉素、氨苄西林、苯唑西林,因为几乎所有的蜡状芽孢杆菌(除炭疽芽孢杆菌之外),都携带β-内酰胺酶基因。虽然炭疽芽孢杆菌携带β-内酰胺酶基因bla1和bla2,但因其表达被抑制而导致对β-内酰胺的敏感性 [30] 。大多数蜡状芽孢杆菌对复方增效磺胺具有抗性 [31] [32] ,虽然抗性水平因菌株而异。同样的,对于磷霉素的抗性在这些细菌类群中普遍存在。有趣的是,研究发现在某些菌株中,抗性相应基因位于移动插入盒(MIC)上 [33] 、或者炭疽芽孢杆菌特异性的γ-噬菌体上 [34] ,提示其具有潜在的可移动性。

蜡状芽孢杆菌对其它抗生素的抗性差异较大而且与菌株相关 [35] [36] 。四种最常见的抗性分别是针对氯林可霉素(林肯酰胺)(多达60%)、四环素(10%~33%)和左氧氟沙星(氟喹诺酮) (约10%)。针对万古霉素与红霉素的抗性并不常见。最后,针对环丙沙星、氯霉素、庆大霉素、利福平、链霉素或者卡那霉素的抗性在狭义的蜡状芽孢杆菌或者苏云金芽孢杆菌中尚未报道。

一个有趣的现象是关于蜡状芽孢杆菌针对某些抗生素的行为:暴露于氨基糖苷类抗生素会诱导蜡状芽孢杆菌致吐毒株的表型转变为缓慢生长的小菌落变种,提示其通过缓慢生长的方式来逃避抗生素的杀菌作用 [37] 。

蜡状芽孢杆菌的这些抗生素抗性基因一般位于染色体上,虽然有些抗性基因位于潜在的可移动组件(如对于磷霉素而言的移动插入盒与噬菌体上)或者位于可移动组件比如质粒上。早在1978年,Bernhard等描述了一个携带四环素抗性的蜡状芽孢杆菌小质粒pBC16。同样的,质粒相关tetA,tetB已在食源性蜡状芽孢杆菌菌株中被发现 [32] 。蜡状芽孢杆菌类群里的细菌具有通过接合和转导方式来相互交换遗传物质的潜力,特别是当遗传因子(比如抗生素抗性基因)位于接合质粒或者可移动的质粒上。

5. 蜡状芽孢杆菌cereulide防治的进展

近年来,全球范围内食品安全事件时有发生,食源性疾病的发生率也居高不下,而Bc在自然界广泛分布,特别是致吐毒株Bce所产毒素cereulide由于耐热、毒性较强引起了人们的极大关注。虽然目前关于Bce的生态位以及cereulide结构与活性的研究取得较大进展,但是针对其所致的呕吐型中毒以及其它健康威胁(如糖尿病)的防治才刚刚起步。目前采用的防治方法包括物化手段(如添加有机酸、萜类化合物、壳聚糖季铵盐、ε-聚赖氨酸)、非特异性的生物抑菌方法(如细菌素、乳酸菌素) [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] 。这些措施均着眼于抑制致吐毒株的生长,而不是阻抑呕吐毒素的合成。即使致吐毒株的生长受抑,其毒素cereulide在食材中已预先合成,仍具有毒性,其含量在0.02 μg/kg~1.83 μg/kg体重时即达到呕吐中毒的剂量 [13] 。抑制食材中cereulide的生物合成应是防治的重点。然而迄今国内外只有一则此类报道:采用食品添加剂长链多聚磷酸盐(polyPs)抑制cereulide的生物合成 [42] 。鉴于所有细菌中都存在polyPs的天然类似物而发挥生理作用,外源添加polyPs会对胞内ATP合成、蛋白质折叠或酶活性产生不利影响 [42] 。若长期使用可能造成一些不良后果,比如:致吐毒株抗性菌株出现。因此探索和开发从源头阻抑cereulide生物合成的防治方法迫在眉睫。

与此同时,还需要监控蜡样芽孢杆菌的耐药性。随着抗生素的普遍使用,蜡样芽孢杆菌能够对抗菌药物产生耐药性,该菌携带抗性基因在自然界中可转移,对人类健康的危害不容小视。

基金项目

本工作在江苏省自然科学基金资助项目(项目号BK20151133)下完成。

文章引用

林 岚,徐旭东. 蜡样芽孢杆菌毒素Cereulide的研究进展

The Research Advances in the Toxin Cereulide Produced by Bacillus cereus[J]. 微生物前沿, 2018, 07(04): 141-148. https://doi.org/10.12677/AMB.2018.74017

参考文献

- 1. 周帼萍, 袁志明. 蜡状芽孢杆菌(Bacillus cereus)污染及其对食品安全的影响[J]. 食品科学, 2007, 28(3): 357-361.

- 2. Hoornstra, D., Andersson, M.A., Teplova, V.V., et al. (2013) Potato Crop as a Source of Emetic Bacillus cereus and Cereulide-Induced Mammalian Cell Toxicity. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79, 3534-3543. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00201-13

- 3. Chaabouni, I., Barkallah, I., Hamdi, C., et al. (2015) Metabolic Capacities and Toxigenic Potential as Key Drivers of Bacillus cereus Ubiquity and Adaptation. Annals of Microbiology, 65, 975-983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13213-014-0941-9

- 4. Mahler, H., Pasi, A., Kramer, J.M., et al. (1997) Fulminant Liver Failure in Association with the Emetic Toxin of Bacillus cereus. New England Journal of Medicine, 336, 1142-1148. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199704173361604

- 5. Tschiedel, E., Rath, P.-M., Steinmann, J., et al. (2015) Lifesaving Liver Transplantation for Multi-Organ Failure Caused by Bacillus cereus Food Poisoning. Pediatr Transplant, 19, E11-E14. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.12378

- 6. Lücking, G., Frenzel, E., Rütschle, A., et al. (2015) Ces Locus Embedded Proteins Control the Non-Ribosomal Synthesis of the Cereulide Toxin in Emetic Bacillus cereus on Multiple Levels. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01101

- 7. US Food and Drug Administration (2013) Bacillus cereus and Other Bacillus spp. [EB/OL]. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~mow/chap12.html

- 8. 章乐怡, 张秀尧, 李毅, 蔡欣欣, 王欣. 婴幼儿奶粉和米粉中蜡样芽胞杆菌及其毒素毒力基因的调查研究[J]. 中国食品卫生杂志, 2014, 26(6): 600-604.

- 9. Ehling-Schulz, M., Frenzel, E. and Gohar, M. (2015) Food-Bacteria Interplay: Pathometabolism of Emetic Bacillus cereus. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 704. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00704

- 10. Ueda, S. and Kuwabara, Y. (1993) An Ecological Study of Bacillus cereus in Rice Crop Processing. Journal of Antibacterial and Antifungal Agents, 21, 499-502.

- 11. Ekman, J.V., Kruglov, A., Andersson, M.A., et al. (2012) Cereulide Produced by Bacillus cereus Increases the Fitness of the Producer Organism in Low-Potassium Environments. Microbiology, 158, 1106-1116. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.053520-0

- 12. Ceuppens, S., Boon, N. and Uyttendaele, M. (2013) Diversity of Bacillus cereus Group Strains Is Reflected in Their Broad Range of Pathogenicity and Diverse Ecological Lifestyles. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 84, 433-450. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12110

- 13. Ceuppens, S., Rajkovic, A., Heyndrickx, M., Tsilia, V., van de Wiele, T., Boon, N. and Uyttendaele, M. (2011) Regulation of Toxin Production by Bacillus cereus and Its Food Safety Implications. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 37, 188-213. https://doi.org/10.3109/1040841X.2011.558832

- 14. Agata, N., Ohta, M. and Yokoyama, K. (2002) Production of Bacillus cereus Emetic Toxin (Cereulide) in Various Foods. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 73, 23-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00692-4

- 15. Rajkovic, A., Uyttendaele, M., Ombregt, S.A., Jaaskelainen, E., Salkinoja-Salonen, M. and Debevere, J. (2006) Influence of Type of Food on the Kinetics and Overall Production of Bacillus cereus Emetic Toxin. Journal of Food Protection, 69, 847-852. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-69.4.847

- 16. Vangoitsenhoven, R., Rondas, D., Crevecoeur, I., D’Hertog, W., Baatsen, P., et al. (2014) Foodborne Cereulide Causes Beta-Cell Dysfunction and Apoptosis. PLoS ONE, 9, e104866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104866

- 17. 崔一芳. 蜡样芽孢杆菌毒素特征及耐药基因tet(45)的可移动性研究[D]: [博士学位论文]. 北京: 中国农业大学博士论文, 2016

- 18. Delbrassinne, L., Bottleldoorn, N., Andjelkovic, M., et al. (2015) An Emetic Bacillus cereus Outbreak in a Kindergarten: Detection and Quantification of Critical Levels of Cereulide Toxin. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 12, 84-87. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2014.1788

- 19. Ehling-Schulz, M., Fricker, M., Grallert, H., Rieck, P., Wagner, M. and Scherer, S. (2006) Cereulide Synthetase Gene Cluster from Emetic Bacillus cereus: Structure and Location on a Mega Virulence Plasmid Related to Bacillus anthracis Toxin Plasmid pXO1. BMC Microbiology, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-6-20

- 20. Dommel, M., Lücking, G., Scherer, S. and Ehling-Schulz, M. (2011) Transcriptional Kinetic Analyses of Cereulidesynthetase Genes with Respect to Growth, Sporulation and Emetic Toxin Production in Bacillus cereus. Food Microbiology, 28, 284-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2010.07.001

- 21. Mei, X., Xu, K., Yang, L., Yuan, Z., Mahillon, J. and Hu, X. (2014) The Genetic Diversity of Cereulide Biosynthesis Gene Cluster Indicates a Composite Transposon Tnces in Emetic Bacillus weihenstephanensis. BMC Microbiology, 14, 149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-14-149

- 22. Modrie, P., Beuls, E. and Mahillon, J. (2010) Differential Transfer Dynamics of pAW63 Plasmid among Members of the Bacillus cereus Group in Food Microcosms. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 108, 888-897. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04488.x

- 23. Van der Auwera, G.A., Timmery, S., Hoton, F. and Mahillon, J. (2007) Plasmid Exchanges among Members of the Bacillus cereus Group in Foodstuffs. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 113, 164-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.030

- 24. Duanis-Assaf, D., Steinberg, D., Chai, Y. and Shemesh, M. (2016) The LuxS Based Quorum Sensing Governs Lactose Induced Biofilm Formation by Bacillus subtilis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 1517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01517

- 25. Lópeza, D., Fischbach, M.A., Chu, F., Losick, R. and Kolter, R. (2009) Structurally Diverse Natural Products That Cause Potassium Leakage Trigger Multicellularity in Bacillus subtilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 106, 280-285. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0810940106

- 26. Qian, Y., Kando, C.K., Thorsen, L., Larsen, N. and Jespersen, L. (2015) Production of Autoinducer-2 by Aerobic Endospore-Forming Bacteria Isolated from the West African Fermented Foods. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 362, fnv186. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnv186

- 27. Auger, S., Krin, E., Aymerich, S. and Gohar, M. (2006) Autoinducer 2 Affects Biofilm Formation by Bacillus cereus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72, 937-941. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.1.937-941.2006

- 28. Zhu, H., Liu, H.J., Ning, S.J. and Gao, Y.L. (2012) The Re-sponse of Type 2 Quorum Sensing in Klebsiella pneumoniae to a Fluctuating Culture Environment. DNA and Cell Biology, 31, 455-459. https://doi.org/10.1089/dna.2011.1375

- 29. Messelhäusser, U., Frenzel, E., Blöchinger, C., Zucker, R., Kämpf, P. and Ehling-chulz, M. (2014) Emetic Bacilluscereus Are More Volatile than Thought: Recent Food Borne Out-breaks and Prevalence Studies in Bavaria (2007-2013). BioMed Research International, 2014, Article ID: 465603. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/465603

- 30. Chen, Y., Succi, J., Tenover, F.C. and Koehler, T.M. (2003) Beta-Lactamase Genes of the Penicillin-Susceptible Bacillus anthracis Sterne Strain. Journal of Bacteriology, 185, 823-830. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.185.3.823-830.2003

- 31. Ombui, J.N., Mathenge, J.M., Kimotho, A.M., Macharia, J.K. and Nduhiu, G. (1996) Frequency of Antimicrobial Resistance and Plasmid Profiles of Bacillus cereus Strains Isolated from Milk. East African Medical Journal, 73, 380-384.

- 32. Rather, M.A., Aulakh, R.S., Gill, J.P., Mir, A.Q. and Hassan, M.N. (2012) Detection and Sequencing of Plasmid Encoded Tetracycline Resistance Determinants (tetA and tetB) from Food-Borne Bacillus cereus Isolates. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 5, 709-712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60111-4

- 33. De Palmenaer, D., Vermeiren, C. and Mahillon, J. (2004) IS231-MIC231 Elements from Bacillus cereus Sensulatoare Modular. Molecular Microbiology, 53, 457-467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04146.x

- 34. Schuch, R. and Fischetti, V.A. (2006) Detailed Genomic Analysis of the Wbeta and Gamma Phages Infecting Bacillus anthracis: Implications for Evolution of Environmental Fitness and Antibiotic Resistance. Journal of Bacteriology, 188, 3037-3051. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.188.8.3037-3051.2006

- 35. Chon, J.W., Kim, J.H., Lee, S.J., Hyeon, J.Y. and Seo, K.H. (2012) Toxin Profile, Antibiotic Resistance, and Phenotypic and Molecular Characterization of Bacillus cereus in Sunsik. Food Microbiology, 32, 217-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2012.06.003

- 36. Ikeda, M., Yagihara, Y., Tatsuno, K., Okazaki, M., Okugawa, S. and Moriya, K. (2015) Clinical Characteristics and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacillus cereus Blood Stream Infections. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, 14, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-015-0104-2

- 37. Frenzel, E., Kranzler, M., Stark, T.D., Hofmann, T. and Ehling-Schulz, M. (2015) The Endospore-Forming Pathogen Bacillus cereus Exploits a Small Colony Variant-Based Diversification Strategy in Response to Aminoglycoside Exposure. mBio, 6, e01172-e01115. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01172-15

- 38. Valero, M. and Salmeron, M.C. (2003) Antibacterial Activity of 11 Essential Oils against Bacillus cereus in Tyndallized Carrot Broth. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 85, 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00484-1

- 39. Galvez, A., Abriouel, H., Lopez, R.L. and Ben Omar, N. (2007) Bacteriocin-Based Strategies for Food Biopreservation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 120, 51-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.06.001

- 40. TerBeek, A. and Brul, S. (2010) To Kill or Not to Kill Bacilli: Opportunities for Food Biotechnology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 21, 168-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.014

- 41. 李南薇, 刘佳, 刘锐, 罗凤娟, 杨公明. 32种食品添加剂对蜡样芽孢杆菌的协同抑菌作用[J]. 中国食品学报, 2015, 15(2): 138-142.

- 42. Frenzel, E., Letzel, T., Scherer, S. and Ehl-ing-Schulz, M. (2011) Inhibition of Cereulidetoxin Synthesis by Emetic Bacillus cereus via Long-Chain Polyphosphates. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77, 1475-1482. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02259-10

- 43. Flores-Urban, K.A., Natividad-Bonifacio, I., Vazquez-Quinones, C.R., Vazquez-Salinas, C. and Quinones-Ramirez, E.I. (2014) Detection of Toxigenic Bacillus cereus Strains Isolated from Vegetables in Mexico City. Journal of Food Protection, 77, 2144-2147. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-479

- 44. Altayar, M. and Sutherland, A.D. (2006) Bacillus cereus Is Common in the Environment But Emetic Toxin Producing Isolates Are Rare. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 100, 7-14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02764.x

- 45. Delbrassinne, L., Andjelkovic, M., Dierick, K., Denayer, S., Mahillon, J. and VanLoco, J. (2012) Prevalence and Levels of Bacillus cereus Emetic Toxin in Ricedishes Randomly Collected from Restaurants and Comparison with the Levels Measured in a Recent Foodborne Outbreak. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 9, 809-814. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2012.1168

- 46. Forghani, F., Kim, J.B. and Oh, D.H. (2014) Enterotoxigenic Profiling of Emetic Toxin- and Enterotoxin-Producing Bacillus cereus, Isolated from Food, Environmental, and Clinical Samples by Multiplex PCR. Journal of Food Science, 79, M2288-M2293. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.12666

- 47. Messelhäusser, U., Kämpf, P., Fricker, M., Ehling-Schulz, M., Zucker, R., Wagner, B., et al. (2010) Prevalence of Emetic Bacillus cereus in Different Ice Creams in Bavaria. Journal of Food Protection, 73, 395-399. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-73.2.395

- 48. Wijnands, L.M., Dufrenne, J.B., Rombouts, F.M., in’t Veld, P.H. and Van Leusden, F.M. (2006) Prevalence of Potentially Pathogenic Bacillus cereus in Food Commodities in the Netherlands. Journal of Food Protection, 69, 2587-2594. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-69.11.2587

NOTES

*通讯作者。