Advances in Clinical Medicine

Vol.

13

No.

12

(

2023

), Article ID:

78230

,

11

pages

10.12677/ACM.2023.13122826

儿童缺铁性贫血与维生素D水平 相关性研究进展

阿依考赛尔·亚力坤1,罗新辉2

1新疆医科大学儿科学院,新疆 乌鲁木齐

2新疆维吾尔自治区儿童医院,新疆 乌鲁木齐

收稿日期:2023年11月27日;录用日期:2023年12月21日;发布日期:2023年12月28日

摘要

铁和维生素D的缺乏被认为是全球两个主要的公共卫生问题。缺铁性贫血(IDA)是因体内铁缺乏致使血红蛋白合成减少而引起的贫血,缺铁性贫血是儿童常见的慢性疾病,不仅会导致儿童身体发育不良、生长缓慢,还会严重影响儿童智力发育。铁是人体必需的微量元素,对维持人体内血红蛋白、肌红蛋白和代谢相关酶的活性起重要作用,可参与人体的各种生理活动。铁调素是维持机体铁稳态的核心调节因子,可以降低机体血清铁水平,是最重要的铁代谢负性调控因子,近年的研究表明,铁调素可作为IDA早期诊断及疗效评估的指标之一。维生素D缺乏也是婴幼儿时期常见的微量营养素缺乏症,维生素D的代谢似乎依赖于铁,铁的缺乏可能会干扰维生素D的激活。该文就目前关于儿童缺铁性贫血与维生素D水平相关性的研究进展进行介绍。

关键词

贫血,缺铁性贫血,铁调素,铁代谢,维生素D,25羟维生素D,骨细胞,维生素D代谢途径,儿童, 相关性,诊断,治疗

Progress in the Correlation between Iron Deficiency Anemia and Vitamin D Levels in Children

Aykawsar Yalkun1, Xinhui Luo2

1Academy of Pediatric, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi Xinjiang

2Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Children’s Hospital, Urumqi Xinjiang

Received: Nov. 27th, 2023; accepted: Dec. 21st, 2023; published: Dec. 28th, 2023

ABSTRACT

Deficiencies in both vitamin D and iron are recognized as two major public health concerns around the globe. Iron deficiency anemia is a common chronic disease in children, which not only leads to poor body development and slow growth of children but also seriously affects their intellectual development. Iron, an essential trace element in human body, plays an important role in maintaining the activities of hemoglobin, myoglobin, and metabolic-related enzymes in human body and can participate in various physiological activities of human body. Patients with iron deficiency are often accompanied by oxygen transport disorders, resulting in metabolic disorders and eventually anemia. Hepcidin is the core regulator of maintaining iron homeostasis, which reduces serum iron levels and is the most important negative regulator of iron metabolism. Recent studies have shown that hepcidin can be used as one of the indicators for the early diagnosis and efficacy evaluation of IDA. Vitamin D deficiency is also a common micronutrient deficiency in infants and young children. Vitamin D metabolism is dependent on iron and its deficiency might disturb vitamin D activation. This paper introduces the current research progress on the correlation between iron deficiency anemia and vitamin D levels in children.

Keywords:Anemia, Iron Deficiency Anemia, Hepcidin, Iron Metabolism, Vitamin D, 25(OH)D, Bone Cells, Vitamin D Metabolic Pathway, Child, Correlation, Diagnosis, Treatment

Copyright © 2023 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

贫血是一个严重的全球公共卫生问题,尤其影响幼儿和孕妇。据世界卫生组织估计,2019年,全球39.8%的儿童(6至59个月) [1] 存在贫血,贫血影响2.93亿5岁以下儿童,占全球同年龄组儿童的47.4% [2] 。这些儿童中的大多数集中在发展中国家 [3] 。国际研究表明,儿童早期贫血会导致短期和长期的后果,从短期来看,患有贫血的儿童的心理、运动和社会情感发展明显低于没有贫血的儿童 [4] [5] [6] [7] ,从长远来看,即使在控制了社会背景变量、性别和出生体重后,儿童贫血也会对认知能力产生长期影响 [8] 。缺铁性贫血(IDA)目前仍然是导致贫血的最主要原因 [9] ,IDA的发病原因有多种,包括饮食结构不合理、慢性出血导致大量铁流失、体内铁吸收不良等,严重影响儿童 [10] [11] [12] 的发育和生长。Juan Zheng等人 [13] 共对2601名6~24个月的儿童进行了调查,贫血的总患病率为26.45%,其中缺铁性贫血儿童占27.33%,研究发现,缺铁性贫血组和非缺铁性贫血组儿童神经行为发育的总DQ值显著低于非贫血组。进一步比较显示,缺铁性贫血组儿童大运动、精细运动和适应性的DQ值均低于无贫血组。铁是人体必需的微量元素,对维持人体内血红蛋白、肌红蛋白和代谢相关酶的活性起重要作用,可参与人体的各种生理活动,铁缺乏可对神经系统、免疫系统、消化系统、造血系统等产生严重影响。铁调素是维持机体铁稳态的核心调节因子,可以降低机体血清铁水平,是最重要的铁代谢负性调控因子。维生素D是铁调素的重要调节因子 [14] ,有研究表明维生素D对铁调素有抑制作用 [15] 。笔者翻阅目前国内外有关缺铁性贫血和维生素D水平相关性研究的相关文献进行综述,以期为儿童缺铁性贫血的诊治提供新思路。

2. 缺铁性贫血

2.1. 缺铁性贫血概述

缺铁性贫血是体内铁缺乏导致血红蛋白合成减少,临床上以小细胞低色素性贫血、血清铁蛋白减少和铁剂治疗有效为特点的贫血症。缺铁性贫血是儿童常见的慢性疾病,不仅导致儿童身体发育不良和发育缓慢,而且严重影响其智力发育 [16] [17] 。铁是人体必需的微量元素,缺铁患者常伴有氧运输障碍导致代谢紊乱,最终贫血 [18] [19] [20] 。目前,饮食治疗、铁制剂,和其他方法经常用于干预IDA,包括增加肝脏的摄入量,瘦肉和豆制品改善儿童的内部环境或直接补充铁剂提高体内的铁水平,促进体内血红蛋白的合成,从而改善贫血的症状 [21] [22] [23] 。Clement等人 [22] 研究发现育龄妇女和幼儿(6~24个月)每周三次食用芙蓉叶餐(HSM,1.71毫克铁/100克餐),他们发现,随着时间的推移,干预组中喂养HSM后幼儿发育不良(p = 0.024)数量有所下降,且干预组的缺铁患病率变化显著低于对照组,为0.3%,提示干预可能有助于改善铁状态。美国的一项调查发现 [23] ,接受含铁强化食品的儿童患贫血和缺铁的风险明显较低,血红蛋白浓度也较高。

2.2. 铁代谢

铁是人类重要的微量元素,它在氧的运输、氧化代谢、细胞增殖和许多催化反应中起着至关重要的作用 [24] 。在人体中,铁是许多血红蛋白和非血红素含铁蛋白的辅助因子。血液蛋白包括负责氧结合和运输的血红蛋白和肌红蛋白,参与氧代谢的过氧化氢酶和过氧化物酶,以及参与电子传递和线粒体呼吸的细胞色素。非血红素含铁蛋白也具有重要的功能,因为这些功能被用于DNA合成、细胞增殖和分化、基因调控、药物代谢和类固醇合成 [25] 。两种最常见的铁态是二价亚铁(Fe2+)和三价铁(Fe3+)。铁输出细胞包括肠上皮细胞、巨噬细胞和肝细胞,它们都能根据需求回收铁 [26] 。十二指肠在膳食铁的吸收中起着非常重要的作用。进入肠粘膜细胞的Fe2+被氧化成Fe3+,一部分与细胞内的去铁蛋白(Apoferritin)结合形成铁蛋白(Ferritin),暂时保存在肠粘膜细胞中,另一部分与细胞质中载体蛋白结合后移出细胞外进入血液,并与肝脏来源的转铁蛋白(Tf)结合,然后被组织吸收、利用,如骨髓中的红细胞生成,肌肉中的肌红蛋白合成,以及所有呼吸细胞中的氧化代谢。脾、肝和骨髓巨噬细胞属于单核/吞噬细胞系统(网状内皮系统),网状内皮系统的任务是从衰老的红细胞中回收铁。随着衰老的红细胞被吞噬,单核/吞噬细胞系统每天回收约25毫克的铁,这意味着大多数人类的铁稳态依赖于铁的循环 [26] 。

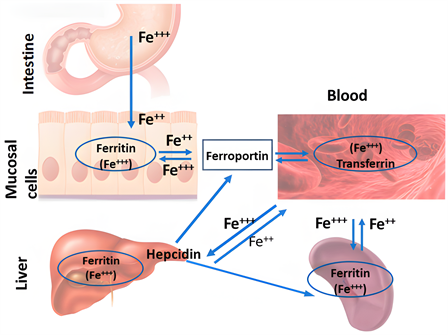

肝脏在铁稳态中具有重要的合成、储存和调节功能 [24] ,通过产生激素hepcidin来控制肠细胞和巨噬细胞在循环中释放铁(见图1)。

从图1可知,十二指肠肠上皮细胞负责膳食铁的吸收。铁被吸收后,在体内与转铁蛋白结合循环,并被不同的组织利用。网状内皮系统,包括脾巨噬细胞,从衰老的红细胞中回收铁。在许多其他功能中,肝脏产生hepcidin。Hepcidin控制肠细胞和巨噬细胞释放铁进入循环,被认为是铁代谢系统的主调节因子。

2.3. 铁调素与铁代谢的关系

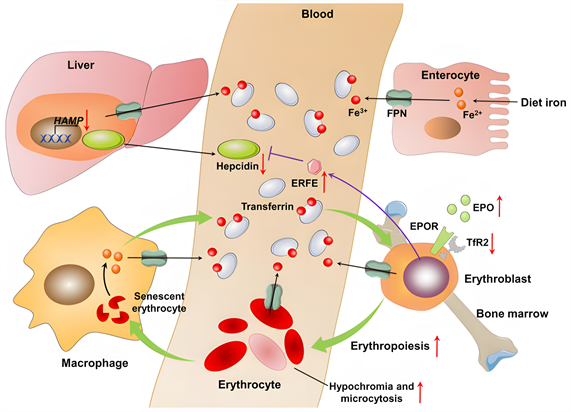

在众多参与铁代谢的蛋白质中,铁调素(hepcidin)是一种肝脏衍生的肽激素,是铁代谢的主要调节因子。这种激素在许多靶组织中起作用,并通过负反馈机制调节系统的铁水平 [24] ,可作为预测铁储存的替代生物标志物 [27] [28] [29] [30] 。铁调素水平可随机体血清铁水平、肝脏铁储存量、缺氧、炎症、红细胞生成素或药物等因素而发生变化 [31] 。Hepcidin与运铁蛋白(FPN)结合,这是唯一已知的铁输出蛋白,然后被溶酶体内化和降解。随后,十二指肠肠上皮细胞、巨噬细胞和肝细胞不能再输出铁,而铁被隔离在这些细胞中。Hepcidin的表达在绝对缺铁或铁需求增加期间表达下调,而在炎症、肝脏和血浆中铁浓度高时表达上调。缺铁通过EPO受体(EPOR)伴侣转铁蛋白受体2 (TfR2)的遗传缺失增加肾红细胞生成素(EPO)的产生和红细胞生成EPO的敏感性,从而增强红细胞生成 [32] 。在绝对缺铁时,铁调素生成的减少导致红细胞和红细胞 [33] 的FPN表达增加,导致铁通过FPN释放到血清中,以缓解血清铁耗竭并保护红细胞免受氧化应激 [34] 。这些数据表明,在铁缺乏的情况下,红系细胞捐献铁以维持其他地方的铁供应,从而降低成红细胞的细胞内铁的可用性(图2)。Hepcidin受三种途径调控:低铁储存、红细胞生成信号和炎症 [35] 。

Figure 1. The main tissues involved in the regulation of systemic iron metabolism

图1. 参与系统铁代谢调节的主要组织

Figure 2. Iron homeostasis in iron deficiency

图2. 铁缺乏时的稳态

从图2可知,关于缺铁的体内平衡。身体中的大多数铁参与红细胞生成、吞噬和巨噬细胞溶解衰老红细胞的过程(浅绿色箭头)。肝细胞产生和分泌的铁调素是系统铁代谢的主要调节因子。在铁缺乏症中,铁调素编码基因HAMP的转录被下调。低铁调素水平通过增加铁输出体铁蛋白(FPN)的活性,增加巨噬细胞的回收和肠细胞对铁的吸收。低铁调素水平也导致铁通过FPN从成红细胞流出,这进一步降低了成红细胞的细胞内铁的可用性。铁缺乏通过增强红细胞生成素(EPO)的产生和通过EPO受体(EPOR)伴侣转铁蛋白的遗传缺失增强红细胞EPO敏感性来刺激红细胞生成受体2 (TfR2)。红细胞生成的增加和成红细胞中铁供应的减少导致红细胞减少或红细胞减少。促红细胞生成素(EPO)刺激成红细胞产生的一种激素——红铁酮(ERFE)也可以抑制铁调素的产生。红色向上箭头表示高程;红色向下箭头表示下降;黑色箭头表示铁调素FPN轴调节的铁稳态;紫色箭头表示成红细胞调节的铁调素表达;绿色箭头表示红细胞生成过程中的铁循环。

3. 维生素D

3.1. 维生素D概述

维生素D是一种重要的类固醇激素 [36] ,它主要是在受到阳光照射后的皮肤中产生的 [36] [37] [38] 。对大多数人来说,晒太阳是维生素D最重要的来源,阳光照射对维生素D合成的影响取决于皮肤色素沉着、体表面积和年龄 [39] 。Kathleen E. Altemose等人在研究中发现,按种族划分,维生素D不足/缺乏的白人儿童贫血的几率比维生素D充足的白人儿童高2.39倍 [40] 。人体可通过2种途径获得维生素D,一种是从食物中获得,另一种是由皮肤中的7-脱氢胆固醇经过波长为280~315 nm的紫外线照射后合成,人体内约90%的维生素D都是通过后者获得的。无论是食物来源的维生素D还是经皮肤合成的维生素D,在发挥其生物学作用前,都需要依次经过肝脏、肾脏的羟化作用,进而合成25-羟维生素D3 [25(OH)D3]及1,25-二羟维生素D3 [1,25(OH)2D3]。25(OH)D3及1,25(OH)2D3均是血液中维生素D的存在形式,相较1,25(OH)2D3而言,25(OH)D3的半衰期更长,大约为2~3周,且其在血液中更为稳定,所以25(OH)D3是反映体内维生素D状态的最佳指标 [41] 。

维生素D缺乏是世界范围内一个重要的儿童健康问题 [36] [37] [38] [42] - [47] 。有研究表明,维生素D缺乏症(VDD)与婴儿死亡率、心血管疾病、癌症、总死亡率、糖尿病、情绪障碍以及结核病和艾滋病等感染的风险增加有关 [48] 。在美国小于21岁儿童和青少年中非常普遍,发病率高达70% [49] [50] ;在一个以人群为基础的荷兰队列中,30%的儿童缺乏维生素D,66%的儿童维生素D不足 [51] ;澳大利亚对维生素D缺乏引起的佝偻病的首次全国估计显示,15岁儿童的发病率为4.9/10万人口 [52] ;韩国一项针对6至12岁儿童的研究发现,59%存在维生素D缺乏症 [53] ;而土耳其的一项研究发现,在土耳其0~16岁儿童中,维生素D缺乏症的患病率为40% [54] ;据估计,生活在非洲的儿童中,约有23%和52%的儿童分别患有维生素D和铁缺乏症 [55] [56] 。

3.2. 维生素D与铁调素

25-羟基维生素D在骨和矿物质代谢中起着至关重要的作用,越来越多的人认为它对免疫功能、细胞增殖和分化以及心血管功能 [57] [58] 也有影响。越来越多的证据表明,维生素D缺乏症也与贫血 [59] [60] [61] [62] 的风险增加有关。维生素D及其代谢物存在于许多组织中,如骨化三醇的受体,骨化三醇是维生素D的活性形式。骨化三醇的产生(调节骨矿物质代谢)是通过肾组织中的1-α-羟化酶的作用发生的。然而,有多个肾外部位,局部产生的骨化三醇调节宿主细胞DNA,并控制维生素D骨骼外的作用。实验数据表明,25OHD水平不足导致骨髓局部骨化三醇生成减少,可能限制促红细胞生成;骨化三醇对促红细胞破裂形成单位有直接增殖作用,与内源性促红细胞生成素协同作用,并上调促红细胞祖细胞 [59] [60] [61] [62] 上的促红细胞生成素受体的表达。局部产生的骨化三醇通过抑制多种免疫细胞表达促炎细胞因子,在调节免疫功能调节中发挥关键作用,从而提供负反馈,防止过度炎症。维生素D的免疫调节作用可能是通过调节系统细胞因子的产生来预防贫血的核心,细胞因子反过来抑制导致贫血发展的特定炎症途径。铁调节蛋白hepcidin在炎症环境中上调,介导铁限制性红细胞生成;hepcidin可能被维生素D的免疫调节作用下调。2014年的一项初步研究发现,补充单剂量维生素D (100,000 IU维生素D)增加血清25OHD水平,在24小时内,与循环的hepcidin水平下降34%有关 [15] 。通过抑制促炎细胞因子和直接抑制hepcidin的表达,维生素D可能确实能有效地动员铁的储存,促进红细胞生成和血红蛋白的合成 [63] 。

3.3. 维生素D与IDA

铁在胶原蛋白的合成和维生素D的代谢中起着重要的作用。铁参与骨代谢,铁对于骨细胞的生长、增殖和分化是必需的,特别是对成骨细胞和破骨细胞。骨稳态的维持依赖于两个重要的细胞,即形成新骨的成骨细胞和溶解旧骨和受损骨的破骨细胞。破骨细胞含有大量的线粒体。线粒体呼吸复合物I和过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体γ共激活因子1β (PGC-1β是关键的线粒体转录调节因子)对破骨细胞分化至关重要。线粒体活性氧(ROS)也是刺激破骨细胞分化和骨组织吸收的重要组成部分。铁在线粒体代谢、ROS的产生、血红素和Fe-S簇的生物合成中起着重要作用,是线粒体呼吸复合体 [64] [65] 的关键组成部分。因此,铁对破骨细胞的分化和骨吸收活性的激活至关重要。因此,细胞内铁含量的减少可导致成骨细胞和破骨细胞的活性和功能紊乱,导致骨稳态失衡,最终导致骨丢失。事实上,缺铁,无论伴有贫血或不伴有贫血,都会导致骨质减少或骨质疏松症,这已经被大量的临床观察和动物研究所证实 [40] 。一项基于大规模人群的研究表明,有IDA病史的患者与无贫血的患者相比,发生骨质疏松的风险为近两倍 [66] 。由缺铁引起的缺氧也会导致骨细胞的活性和功能紊乱。铁与细胞中的氧感应密切相关,由于铁对氧的运输是必不可少的,铁的缺乏会由于对细胞和组织的氧输送减少而导致低氧条件(缺氧)。缺氧诱导因子(HIFs)是由一个氧敏感的α亚基和一个稳定的β亚基组成的异二聚体转录因子,是细胞对缺氧 [67] 反应的关键介质。综上所述,铁缺乏可通过诱导缺氧和维生素D代谢紊乱。

维生素D与缺铁性贫血之间的联系已被广泛报道 [68] - [77] 。Blanco-Rojo等人 [76] 证明,铁缺乏妇女的维生素D缺乏或不足非常高。然而,通过铁强化饮食恢复铁状态并不影响25(OH)D水平;Grindulis等人 [78] 表明,亚洲儿童缺铁与维生素D水平降低之间存在显著关联;Qader等人 [79] 发现,与铁正常的儿童相比,伊拉克铁缺乏症儿童的血清维生素D水平较低;El-Adawy等人 [80] 证实,在患有IDA的埃及青少年女性中,维生素D缺乏症的频率高于健康对照组;Jin等人 [81] 发现,67%的IDA婴儿存在维生素D缺乏症;Grmonus等人发现,血浆维生素D水平较低的儿童的血红蛋白和血清铁水平显著降低 [78] 。这些数据表明,铁可能通过调节维生素D羟化酶的表达,参与了维生素D的代谢,提示适当的补铁可能激活维生素D。然而,在英国 [78] 的22个月大的亚洲婴儿、在印度北部 [72] 住院的儿童或在韩国 [82] 诊断为IDA的儿童中,维生素D状态与铁蛋白水平无关。机制研究表明,维生素D可能通过抑制肝皮素的转录或抑制促炎细胞因子来降低其水平,从而改善铁缺乏,从而允许铁吸收。

综上所述,维生素D缺乏和IDA都是儿童时期常见的营养性疾病,关于IDA的治疗,以往较注重铁元素的补充,但经研究证实,维生素D在IDA的预防及治疗中有较为积极的意义。

4. 小结与展望

缺铁性贫血与铁调素及维生素D水平密切相关。铁调素对铁代谢起负性调控作用,而维生素D作为铁调素的重要调节因子可引发缺铁性贫血。尽管缺铁性贫血与维生素D水平之间的因果关系仍存在争议,但维生素D的作用已经为一些新的临床应用进展提供了前景,尽管目前维生素D在铁稳态中的研究取得了进展,但仍需要进一步研究来验证缺铁性贫血和维生素D水平之间的相关性,为我国缺铁性贫血患儿的诊断及治疗开辟了一个新的前景,为儿童健康成长保驾护航。

文章引用

阿依考赛尔·亚力坤,罗新辉. 儿童缺铁性贫血与维生素D水平相关性研究进展

Progress in the Correlation between Iron Deficiency Anemia and Vitamin D Levels in Children[J]. 临床医学进展, 2023, 13(12): 20072-20082. https://doi.org/10.12677/ACM.2023.13122826

参考文献

- 1. WHO (2021) Anaemia in Children. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.ANAEMIACHILDRENREGv?lang=en

- 2. McLean, E., Cogswell, M., Egli, I., Wojdyla, D. and De Benoist, B. (2009) Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutrition, 12, 444-454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002401

- 3. Stoltzfus, R.J., Mullany, L. and Black, R.E. (2005) Iron Defi-ciency Anaemia. In: Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors, World Health Organization, Geneva, 163-209.

- 4. Greacen, J.R. and Walsh, E.J. (2004) NAPL Containment Using in Situ Solidification. In: Contaminated Soils, Sediments and Water, Kluwer Academic Pub-lishers, Boston, 477-483. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-23079-3_31

- 5. Lozoff, B., Wolf, A.W. and Jimenez, E. (1996) Iron-Deficiency Anemia and Infant Development: Effects of Extended Oral Iron Therapy. The Journal of Pediat-rics, 129, 382-389. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70070-7

- 6. Idjradinata, P. and Pollitt, E. (1993) Re-versal of Developmental Delays in Iron-Deficient Anaemic Infants Treated with Iron. The Lancet, 341, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(93)92477-B

- 7. Lozoff, B., Brittenham, G.M., Wolf, A.W., McClish, D.K., Kuhnert, P.M., Jimenez, E., Jimenez, R., Mora, L.A., Gomez, I. and Krauskoph, D. (1987) Iron Deficiency Anemia and Iron Therapy Effects on Infant Developmental Test Performance. Pediatrics, 79, 981-995. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.79.6.981

- 8. Lozoff, B., Jimenez, E., Hagen, J., Mollen, E. and Wolf, A.W. (2000) Poorer Behavioral and Developmental Outcome More than 10 Years after Treatment for Iron Deficiency in Infancy. Pe-diatrics, 105, e51. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.105.4.e51

- 9. Kassebaum, N.J., Jasrasaria, R., Naghavi, M., et al. (2014) A System-atic Analysis of Global Anemia Burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood, 123, 615-624. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325

- 10. Gwetu, T.P., Chhagan, M.K., Taylor, M., Kauchali, S. and Craib, M. (2017) Anaemia Control and the Interpretation of Biochemical Tests for Iron Status in Children. BMC Re-search Notes, 10, Article No. 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2472-5

- 11. Geletu, A., Lelisa, A. and Baye, K. (2019) Provision of Low-Iron Micronutrient Powders on Alternate Days Is Associated with Lower Prevalence of Anaemia, Stunting, and Improved Motor Milestone Acquisition in the First Year of Life: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Rural Ethiopia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15, e12785. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12785

- 12. Rodrigo, R., Allen, A., Manampreri, A., et al. (2018) Haemoglobin Vari-ants, Iron Status and Anaemia in Sri Lankan Adolescents with Low Red Cell Indices: A Cross Sectional Survey. Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases, 71, 11-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2018.01.003

- 13. Zheng, J., Liu, J. and Yang, W. (2021) Association of Iron-Deficiency Anemia and Non-Iron-Deficiency Anemia with Neurobehavioral Development in Children Aged 6-24 Months. Nutrients, 13, Article No. 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103423

- 14. Smith, E.M., Alvarez, J.A., Kearns, M.D., et al. (2017) High-Dose Vita-min D3 Reduces Circulating Hepcidin Concentrations: A Pilot, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Healthy Adults. Clinical Nutrition, 36, 980-985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.06.015

- 15. Bacchetta, J., Za-ritsky, J.J., Sea, J.L., et al. (2013) Suppression of Iron-Regulatory Hepcidin by Vitamin D. Journal of the American So-ciety of Nephrology, 25, 564-572. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2013040355

- 16. Gelaw, Y., Woldu, B. and Melku, M. (2019) The Role of Reticulocyte Hemoglobin Content for Diagnosis of Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia, and Monitoring of Iron Therapy: A Literature Review. Clinical Laboratory, 65. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.190315

- 17. Gafter-Gvili, A., Schechter, A. and Rozen-Zvi, B. (2019) Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Acta Haematologica, 142, 44-50. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496492

- 18. Eltayeb, R., Rayis, D.A., Sharif, M.E., Ahmed, A.B.A., Elhardello, O. and Adam, I. (2019) The Prevalence of Serum Magnesium and Iron Deficiency Anaemia among Sudanese Women in Early Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 113, 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/try109

- 19. Field, M.S., Mithra, P., Estevez, D. and Peña-Rosas, J.P. (2020) Wheat Flour Fortification with Iron for Reducing Anaemia and Improving Iron Status in Populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD011302. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011302.pub2

- 20. Keeler, B.D., Dickson, E.A., Simpson, J.A., et al. (2019) The Impact of Pre-Operative Intravenous Iron on Quality of Life after Colorectal Cancer Surgery: Outcomes from the In-travenous Iron in Colorectal Cancer-Associated Anaemia (IVICA) Trial. Anaesthesia, 74, 714-725. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14659

- 21. Rogers, B., Kramer, J., Smith, S., Bird, V. and Rosenberg, E.I. (2017) So-dium Chloride Pica Causing Recurrent Nephrolithiasis in a Patient with Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Case Report. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 11, Article No. 325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1499-5

- 22. Kubuga, C.K., Hong, H.G. and Song, W.O. (2019) Hibiscus sabdariffa Meal Improves Iron Status of Childbearing Age Women and Prevents Stunting in Their Toddlers in Northern Ghana. Nutrients, 11, Article No. 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010198

- 23. de-Regil, L.M., Jefferds, M.E.D. and Peña-Rosas, J.P. (2017) Point-of-Use Fortification of Foods with Micronutrient Powders Containing Iron in Children of Preschool and School-Age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017, CD009666. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009666.pub2

- 24. Yiannikourides, A. and Latunde-Dada, G.O. (2019) A Short Review of Iron Metabolism and Pathophysiology of Iron Disorders. Medicines (Basel), 6, Article No. 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines6030085

- 25. Pantopoulos, K., Porwal, S.K., Tartakoe, A. and Devireddy, L. (2012) Mechanisms of Mammalian Iron Homeostasis. Biochemistry, 51, 5705-5724. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi300752r

- 26. Waldvogel-Abramowski, S., Waeber, G., Gassner, C., et al. (2014) Physi-ology of Iron Metabolism. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy, 41, 213-221. https://doi.org/10.1159/000362888

- 27. Zaritsky, J., Young, B., Wang, H.J., Westerman, M., Olbina, G., Nemeth, E., Ganz, T., Rivera, S., Nissenson, A.R. and Salusky, I.B. (2009) Hepcidina Potential Novel Biomarker for Iron Status in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 4, 1051-1056. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.05931108

- 28. Weiss, G., Theurl, I., Eder, S., Koppelstaetter, C., Kurz, K., Sonnweber, T., Kobold, U. and Mayer, G. (2009) Serum Hepcidin Concentration in Chronic Haemodialysis Patients: Associations and Effects of Dialysis, Iron and Erythropoietin Therapy. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 39, 883-890. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02182.x

- 29. Mercadal, L., Metzger, M., Haymann, J.P., Thervet, E., Boffa, J.J., Flamant, M., Vrtovsnik, F., Houillier, P., Froissart, M. and Stengel, B. (2014) The Relation of Hepcidin to Iron Disorders, Inflammation and Hemoglobin in Chronic Kidney Disease. PLOS ONE, 9, e99781. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099781

- 30. Takasawa, K., Takaeda, C., Maeda, T. and Ueda, N. (2014) Hepcidin-25, Mean Corpuscular Volume, and Ferritin as Predictors of Response to Oral Iron Supplementation in Hemo-dialysis Patients. Nutrients, 7, 103-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7010103

- 31. Sangkhae, V. and Nemeth, E. (2017) Regulation of the Iron Homeostatic Hormone Hepcidin. Advances in Nutrition, 8, 126-136. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.013961

- 32. Nai, A., Li-donnici, M.R., Rausa, M., Mandelli, G., Pagani, A., Silvestri, L., Ferrari, G. and Camaschella, C. (2015) The Second Transferrin Receptor Regulates Red Blood Cell Production in Mice. Blood, 125, 1170-1179. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-08-596254

- 33. Zhang, D.L., Senecal, T., Ghosh, M.C., Ollivierre-Wilson, H., Tu, T. and Rouault, T.A. (2011) Hepcidin Regulates Ferroportin Expression and Intracellular Iron Homeostasis of Erythroblasts. Blood, 118, 2868-2877. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-01-330241

- 34. Zhang, D.L., Ghosh, M.C., Ollivierre, H., Li, Y. and Rouault, T.A. (2018) Ferroportin Deficiency in Erythroid Cells Causes Serum Iron Deficiency and Promotes Hemolysis Due to Oxidative Stress. Blood, 132, 2078-2087. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-04-842997

- 35. Ganz, T. (2011) Hepcidin and Iron Regulation, 10 Years Later. Blood, 117, 4425-4433. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-01-258467

- 36. Al Shaikh, A.M., Abaalkhail, B., Soliman, A., Kaddam, I., Aseri, K., Al Saleh, Y., et al. (2016) Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Calcium Homeostasis in Saudi Children. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology, 8, 461-467. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.3301

- 37. Ward, L.M., Gaboury, I., Ladhani, M. and Zlotkin, S. (2007) Vitamin D-Deficiency Rickets among Children in Canada. CMAJ, 177, 161-166. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.061377

- 38. Flores, M., Macias, N., Lozada, A., Sánchez, L.M., Díaz, E. and Barquera, S. (2013) Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels among Mexican Children Ages 2 y to 12 y: A National Survey. Nutrition, 29, 802-804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2012.12.024

- 39. Holick, M.F. (2004) Sunlight and Vitamin D for Bone Health and Prevention of Autoimmune Diseases, Cancers, and Cardiovascular Disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 80, 1678S-1688S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S

- 40. Altemose, K.E., Kumar, J., Portale, A.A., et al. (2018) Vitamin D In-sufficiency, Hemoglobin, and Anemia in Children with Chronic Kidney Disease. Pediatric Nephrology, 33, 2131-2136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-4020-5

- 41. Subramanian, A. and Gernand, A.D. (2019) Vitamin D Metabo-lites across the Menstrual Cycle: A Systematic Review. BMC Women’s Health, 19, Article No. 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0721-6

- 42. Rasoul, M.A., Al-Mahdi, M., Al-Kandari, H., Dhaunsi, G.S. and Haider, M.Z. (2016) Low Serum Vitamin-D Status Is Associated with High Prevalence and Early Onset of Type-1 Dia-betes Mellitus in Kuwaiti Children. BMC Pediatrics, 16, Article No. 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0629-3

- 43. Al-Ghannami, S.S., Sedlak, E., Hussein, I.S., Min, Y., Al-Shmmkhi, S.M., Al-Qufi, H.S., et al. (2016) Lipid-Soluble Nutrient Status of Healthy Omani School Children before and after Intervention with Oily Fish Meal or Re-Esterified Triacylglycerol Fish Oil. Nutrition, 32, 73-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.07.014

- 44. Bener, A., Al-Ali, M. and Hoffmann, G.F. (2009) High Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Young Children in a Highly Sunny Humid Country: A Global Health Problem. Minerva Pe-diatrics, 61, 15-22.

- 45. Zhao, X., Xiao, J., Liao, X., Cai, L., Xu, F., Chen, D., et al. (2015) Vitamin D Status among Young Children Aged 1-3 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study in Wuxi, China. PLOS ONE, 10, e0141595. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141595

- 46. Zhu, Z., Zhan, J., Shao, J., Chen, W., Chen, L., Li, W., et al. (2012) High Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency among Children Aged 1 Month to 16 Years in Hangzhou, China. BMC Public Health, 12, Article No. 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-126

- 47. Gordon, C.M., Feldman, H.A., Sinclair, L., Williams, A.L., Klein-man, P., Perez-Rossello, J., et al. (2008) Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency among Healthy Infants and Toddlers. Ar-chives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 162, 505-512. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.6.505

- 48. Anderson, J.L., May, H.T., Horne, B.D., Bair, T.L., Hall, N.L., Carlquist, J.F., et al. (2010) Relation of Vitamin D Deficiency to Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Disease Status, and Inci-dent Events in a General Healthcare Population. American Journal of Cardiology, 106, 963-968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.027

- 49. Kumar, J., Muntner, P., Kaskel, F.J., Hailpern, S.M. and Mel-amed, M.L. (2009) Prevalence and Associations of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Deficiency in US Children: NHANES 2001-2004. Pediatrics, 24, e362-e370. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0051

- 50. Holick, M.F. (2007) Vitamin D Deficiency. The New England Jour-nal of Medicine, 357, 266-281. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra070553

- 51. Voortman, T., van den Hooven, E.H., Heijboer, A.C., Hofman, A., Jaddoe, V.W. and Franco, O.H. (2015) Vitamin D Deficiency in School-Age Children Is Associated with Sociodemo-graphic and Lifestyle Factors. The Journal of Nutrition, 145, 791-798. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.208280

- 52. Munns, C.F., Simm, P.J., Rodda, C.P., Garnett, S.P., Zacharin, M.R., Ward, L.M., et al. (2012) Incidence of Vitamin D Deficiency Rickets among Australian Children: An Australian Paediat-ric Surveillance Unit Study. The Medical Journal of Australia, 196, 466-468. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.10662

- 53. Roh, Y.E., Kim, B.R., Choi, W.B., Kim, Y.M., Cho, M.J., Kim, H.Y., et al. (2016) Vitamin D Deficiency in Children Aged 6 to 12 Years: Single Center’s Experience in Busan. Annals of Pediat-ric Endocrinology & Metabolism, 21, 149-154. https://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2016.21.3.149

- 54. Andıran, N., Çelik, N., Akça, H. and Doğan, G. (2012) Vitamin D Deficiency in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Re-search in Pediatric Endocrinology, 4, 25-29. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.574

- 55. Mogire, R.M., Mutua, A., Kimita, W., Kamau, A., Bejon, P., Pettifor, J.M., Adeyemo, A., Williams, T.N. and Atkinson, S.H. (2020) Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 8, e134-e142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30457-7

- 56. Muriuki, J.M., Mentzer, A.J., Webb, E.L., Morovat, A., Kimita, W., Ndungu, F.M., Macharia, A.W., Crane, R.J., Berkley, J.A., Lule, S.A., et al. (2020) Estimating the Burden of Iron Deficiency among African Children. BMC Medicine, 18, Article No. 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-1502-7

- 57. Bikle, D. (2009) Nonclassic Actions of Vitamin D. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 94, 26-34. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-1454

- 58. Shroff, R., Knott, C. and Rees, L. (2010) The Virtues of Vitamin D—But How Much Is Too Much? Pediatric Nephrology, 25, 1607-1620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1499-9

- 59. Saab, G., Young, D.O., Gincherman, Y., Giles, K., Norwood, K. and Coyne, D.W. (2007) Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and the Safety and Effectiveness of Monthly Ergocalciferol in Hemodialysis Patients. Nephron Clinical Practice, 105, c132-c138. https://doi.org/10.1159/000098645

- 60. Armas, L.A. and Heaney, R.P. (2011) Vitamin D: The Iceberg Nutrient. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 21, 134-139. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2010.09.002

- 61. Alon, D.B., Chaimovitz, C., Dvilansky, A., Lugassy, G., Douvdevani, A., Shany, S. and Nathan, I. (2002) Novel Role of 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) in Induction of Erythroid Progenitor Cell Proliferation. Experimental Hematology, 30, 403-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-472X(02)00789-0

- 62. Aucella, F., Scalzulli, R.P., Gatta, G., Vigilante, M., Carella, A.M. and Stallone, C. (2003) Calcitriol Increases Burst-Forming Unit-Erythroid Proliferation in Chronic Renal Failure. A Synergistic Effect with r-HuEpo. Nephron Clinical Practice, 95, c121-c127. https://doi.org/10.1159/000074837

- 63. Smith, E.M. and Tangpricha, V. (2015) Vitamin D and Anemia: Insights into an Emerging Association. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 22, 432-438. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000199

- 64. Xu, W., Barrientos, T. and Andrews, N.C. (2013) Iron and Copper in Mitochondrial Diseases. Cell Metabolism, 17, 319-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.02.004

- 65. Dixon, S.J. and Stockwell, B.R. (2014) The Role of Iron and Re-active Oxygen Species in Cell Death. Nature Chemical Biology, 10, 9-17. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1416

- 66. Yang, J., Li, Q., Feng, Y., et al. (2023) Iron Deficiency and Iron Defi-ciency Anemia: Potential Risk Factors in Bone Loss. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24, Article No. 6891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24086891

- 67. Semenza, G.L. (2012) Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Physiology and Medicine. Cell, 148, 399-408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021

- 68. Toxqui, L., Perez-Granados, A.M., Blanco-Rojo, R., Wright, I., de la Piedra, C. and Vaquero, M.P. (2014) Low Iron Status as a Factor of Increased Bone Resorption and Effects of an Iron and Vitamin D-Fortified Skimmed Milk on Bone Remodelling in Young Spanish Women. European Journal of Nutrition, 53, 441-448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-013-0544-4

- 69. Sim, J.J., Lac, P.T., Liu, I.L.A., Meguerditchian, S.O., Kumar, V.A., Kujubu, D.A., et al. (2010) Vitamin D Deficiency and Anemia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Annals of Hematology, 89, 447-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-009-0850-3

- 70. Lee, J.A., Hwang, J.S., Hwang, I.T., Kim, D.H., Seo, J.H. and Lim, J.S. (2015) Low Vitamin D Levels Are Associated with both Iron Deficiency and Anemia in Children and Adoles-cents. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, 32, 99-108. https://doi.org/10.3109/08880018.2014.983623

- 71. Liu, T., Zhong, S., Liu, L., Liu, S., Li, X. and Zhou, T. (2015) Vitamin D Deficiency and the Risk of Anemia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Renal Failure, 37, 929-934. https://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1052979

- 72. Sharma, S., Jain, R. and Dabla, P.K. (2015) The Role of 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Deficiency in Iron Deficient Children of North India. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 30, 313-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-014-0449-x

- 73. Atkinson, M.A., Melamed, M.L., Kumar, J., et al. (2014) Vitamin D, Race, and Risk for Anemia in Children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 164, 153-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.08.060

- 74. Sooragonda, B., Bhadada, S.K., Shah, V.N., Malhotra, P., Ahluwalia, J. and Sachdeva, N. (2015) Effect of Vitamin D Replacement on Hemoglobin Concentration in Subjects with Concurrent Iron-Deficiency Anemia and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized, Single-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Acta Haematologica, 133, 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000357104

- 75. Perlstein, T.S., Pande, R., Berliner, N. and Vanasse, G.J. (2011) Preva-lence of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Deficiency in Subgroups of Elderly Persons with Anemia: Association with Anemia of Inflammation. Blood, 117, 2800-2806. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-09-309708

- 76. Blanco-Rojo, R., Perez-Granados, A.M., Toxqui, L., et al. (2013) Relationship between Vitamin D Deficiency, Bone Remodeling and Iron Status in Iron-Deficient Young Women Consuming an Iron-Fortified Food. European Journal of Nutrition, 52, 695-703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-012-0375-8

- 77. Monlezun, D.J., Camargo, C.A., Mullen, J.T., et al. (2015) Vita-min D Status and the Risk of Anemia in Community-Dwelling Adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2006. Medicine (Baltimore), 94, e1799. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001799

- 78. Grindulis, H., Scott, P.H., Belton, N.R. and Wharton, B.A. (1986) Combined Deficiency of Iron and Vitamin D in Asian Toddlers. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 61, 843-848. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.61.9.843

- 79. Qader, E.A. and Alkhateeb, N.E. (2016) Vitamin D Status in Children with Iron Deficiency and/or Anemia. International Journal of Pediatrics, 4, 3571-3577.

- 80. El-Adawy, E.H., Zahran, F.E., Shaker, G.A. and Seleem, A. (2019) Vitamin D Status in Egyptian Adolescent Females with Iron Deficiency Ane-mia and Its Correlation with Serum Iron Indices. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders—Drug Targets, 19, 519-525. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530318666181029160242

- 81. Jin, H.J., Lee, J.H. and Kim, M.K. (2013) The Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency in Iron-Deficient and Normal Children under the Age of 24 Months. Blood Re-search, 48, 40-45. https://doi.org/10.5045/br.2013.48.1.40

- 82. Yoon, J.W., Kim, S.W., Yoo, E.G. and Kim, M.K. (2012) Prevalence and Risk Factors for Vitamin D Deficiency in Children with Iron Deficiency Anemia. Korean Journal of Pediatrics, 55, 206-211. https://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2012.55.6.206