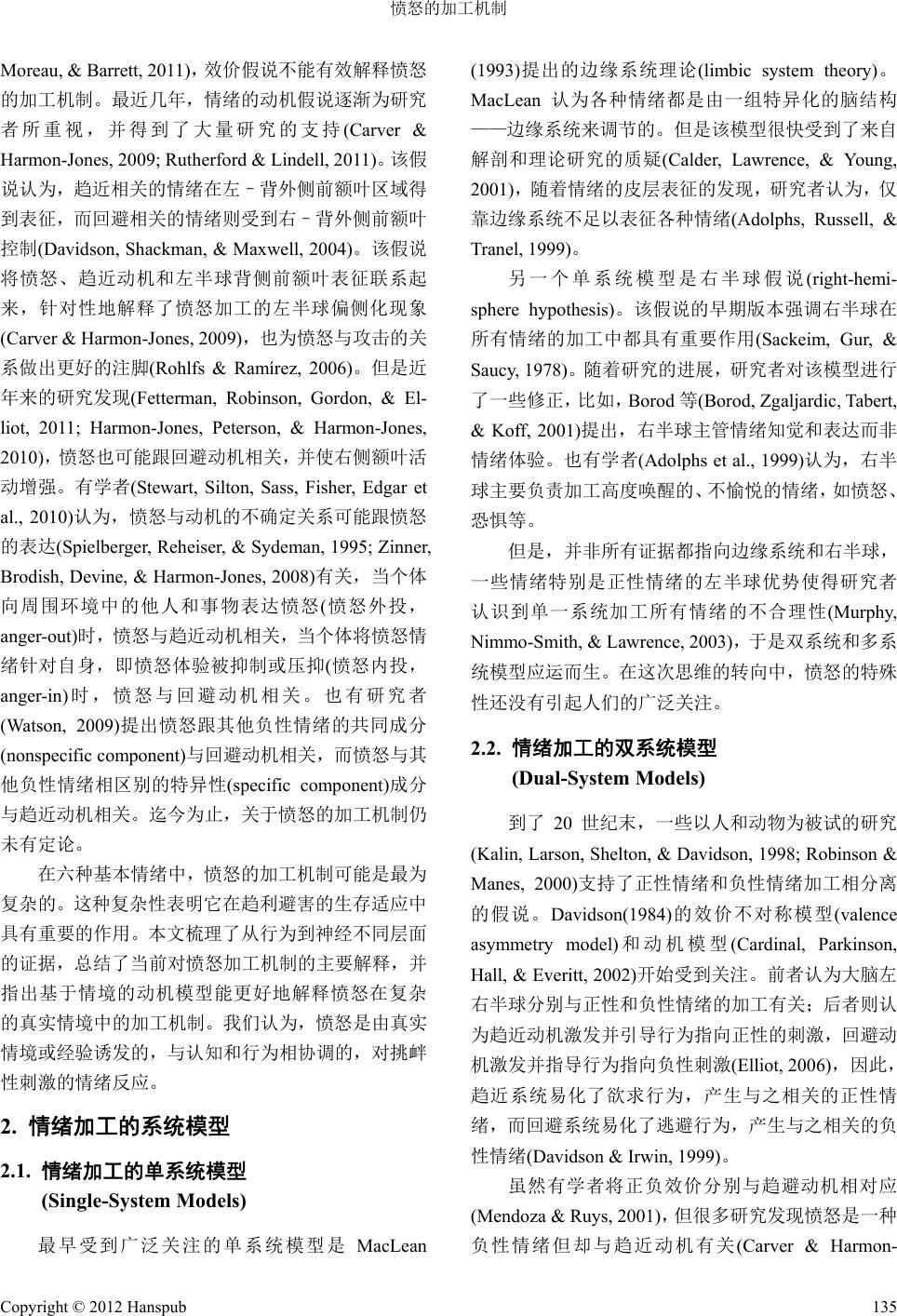

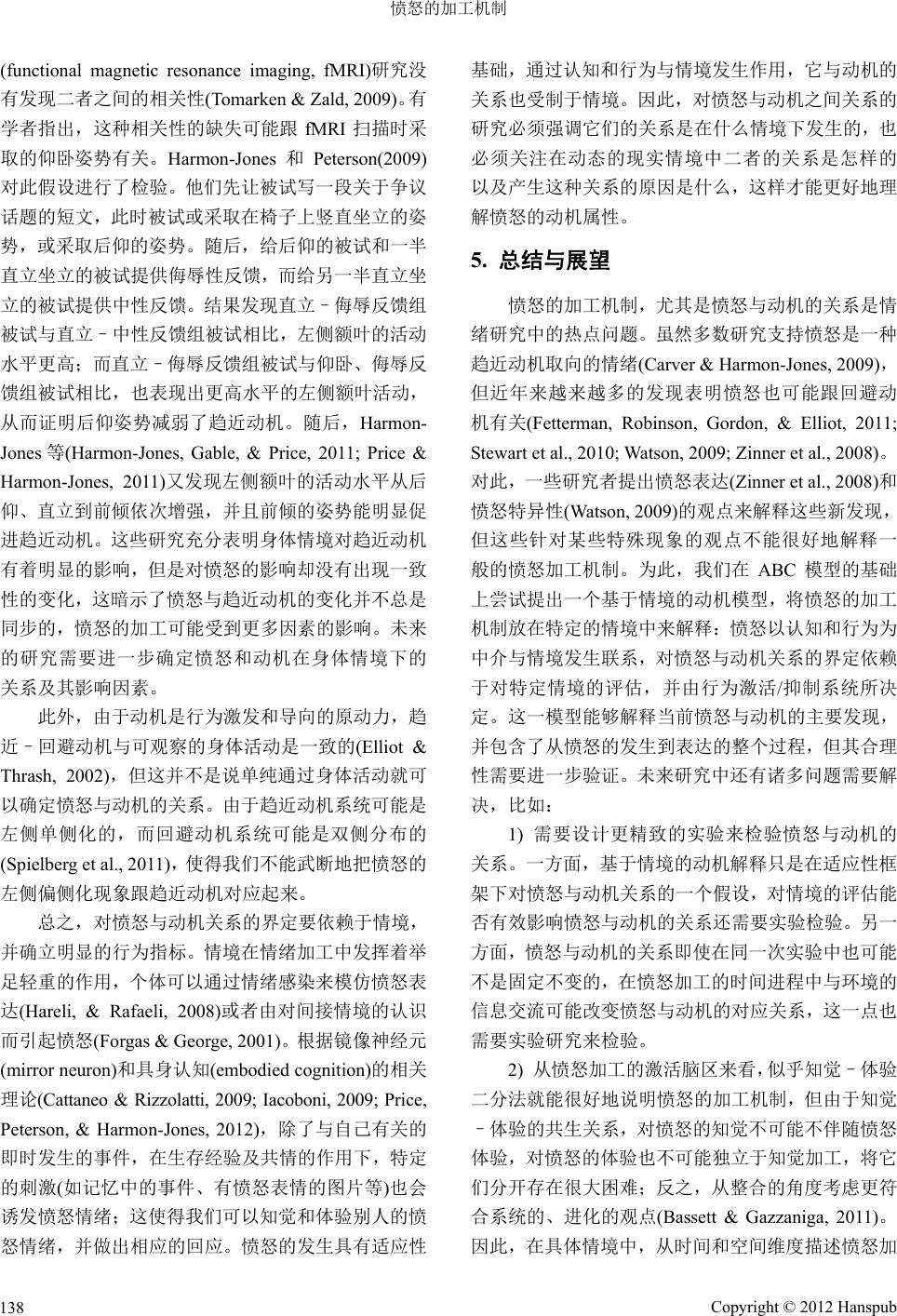

Advances in Psychology 心理学进展, 2012, 2, 134-140 http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/ap.2012.23022 Published Online July 2012 (http://www.hanspub.org/journal/ap) The Process Mechanism of Anger* ——From Valence to Motivation Xiuj uan Jing1, Yifen g W ang2, Rongyan Wang1, Hong Li1,3 1School of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing 2School of Life Science and Technology, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 3Research Center of Psychological Development and Education, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian Email: lihong@swu.edu.cn Received: May 4th, 2012; revised: May 18th, 2012; accepted: May 28th, 2012 Abstract: Anger is a kind of emotion caused by provocative stimuli. According to the valence hypothesis and the motivation hypothesis, anger is a negative emotion prone to approach motivation. Recent behavioral and neuroimaging studies, however, challenged these hypotheses. Some researchers explained these new findings in opinions of anger expression or anger specificity. These opinions were efficient but limited. A contextually dependent view of motivation model might be adopted to better understand the mechanism of anger both in general situation and in special situation. It regarded anger as the reaction to provocative stimuli, which was induced by real sit uat i on or ex peri ence and w as i n conf ormity wit h m ot i vation a nd behavior. Keywords: Anger; Valence; Motivation; Lateralization; Situation 愤怒的加工机制* ——从效价到动机 荆秀娟 1,王一峰 2,王荣燕 1,李 红1,3 1西南大学心理学院,重庆 2电子科技大学生命科学与技术学院,成都 3辽宁师范大学心理发展与教育研究中心,大连 Email: lihong@swu.edu.cn 收稿日期:2012 年5月4日;修回日期:2012 年5月18 日;录用日期:2012 年5月28 日 摘 要:愤怒是一种由挑衅刺激诱发的情绪。情绪的效价假说和动机假说认为愤怒是一种有趋近动机 倾向的负性情绪。然而,最近的行为和神经成像研究都对这两种假说提出了质疑,研究者用愤怒表达 和特异性等观点来解释这些新发现,但这些解释仍有局限性。情景化的动机模型可能更好地解释愤怒 在一般情境和特殊情境下的加工机制,即愤怒是由真实情境或经验诱发的,与动机和行为具有一致性 的,对挑衅性刺激的反应。 关键词:愤怒;效价;动机;偏侧化;情境 1. 引言 愤怒是一种由挑衅引起的,强烈的、不舒服的、 情绪化的反应(Videbeck, 2010 )。它是六种基本情绪之 一(Ekman, 1999),是一种典型的负性情绪。根据情绪 的效价假说,大脑左半球主要负责积极情绪的加工, 右半球主要负责消极情绪的加工。但是大量研究表 明 (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Lindquist, Wager, Kober, *资助信息:国家自然科学基金项目(81171289)资助。 Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 134  愤怒的加工机制 Moreau, & Barrett, 2011),效价假说不能有效解释愤怒 的加工机制。最近几年,情绪的动机假说逐渐为研究 者所重视,并得到了大量研究的支持(Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Rutherford & Lindell, 2011)。该假 说认为,趋近相关的情绪在左–背外侧前额叶区域得 到表征,而回避相关的情绪则受到右–背外侧前额叶 控制(Davidson, Shackman, & Maxwell, 2004)。该假说 将愤怒、趋近动机和左半球背侧前额叶表征联系起 来,针对性地解释了愤怒加工的左半球偏侧化现象 (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009),也为愤怒与攻击的关 系做出更好的注脚(Rohlfs & Ramírez, 2006)。但是近 年来的研究发现(Fetterman, Robinson, Gordon, & El- liot, 2011; Harmon-Jones, Peterson, & Harmon-Jones, 2010),愤怒也可能跟回避动机相关,并使右侧额叶活 动增强。有学者(Stewart, Silton, Sass, Fisher, Edgar et al., 2010)认为,愤怒与动机的不确定关系可能跟愤怒 的表达(Spielberger, Reheiser, & Sydeman, 1995; Zinner, Brodish, Devine, & Harmon-Jones, 2008)有关,当个体 向周围环境中的他人和事物表达愤怒(愤怒外投, anger-out)时,愤怒与趋近动机相关,当个体将愤怒情 绪针对自身,即愤怒体验被抑制或压抑(愤怒内投, anger-in)时,愤怒与回避动机相关。也有研究者 (Watson, 2009)提出愤怒跟其他负性情绪的共同成分 (nonspecific component)与回避动机相关,而愤怒与其 他负性情绪相区别的特异性(specific component)成分 与趋近动机相关。迄今为止,关于愤怒的加工机制仍 未有定论。 在六种基本情绪中,愤怒的加工机制可能是最为 复杂的。这种复杂性表明它在趋利避害的生存适应中 具有重要的作用。本文梳理了从行为到神经不同层面 的证据,总结了当前对愤怒加工机制的主要解释,并 指出基于情境的动机模型能更好地解释愤怒在复杂 的真实情境中的加工机制。我们认为,愤怒是由真实 情境或经验诱发的,与认知和行为相协调的,对挑衅 性刺激的情绪反应。 2. 情绪加工的系统模型 2.1. 情绪加工的单系统模型 (Single-System Models) 最早受到广泛关注的单系统模型是 MacLean (1993)提出的边缘系统理论(limbic system theory)。 MacLean 认为各种情绪都是由一组特异化的脑结构 ——边缘系统来调节的。但是该模型很快受到了来自 解剖和理论研究的质疑 (Calder, Lawrence, & Young, 2001),随着情绪的皮层表征的发现,研究者认为,仅 靠边缘系统不足以表征各种情绪(Adolphs, Russell, & Tranel, 1999)。 另一个单系统模型是右半球假说(right-hemi- sphere hypothesis)。该假说的早期版本强调右半球在 所有情绪的加工中都具有重要作用(Sackeim, Gur, & Saucy, 1978)。随着研究的进展,研究者对该模型进行 了一些修正,比如,Borod 等(Borod, Zgaljardic, Tabert, & Koff, 2001)提出,右半球主管情绪知觉和表达而非 情绪体验。也有学者(Adolphs et al., 1999)认为,右半 球主要负责加工高度唤醒的、不愉悦的情绪,如愤怒、 恐惧等。 但是,并非所有证据都指向边缘系统和右半球, 一些情绪特别是正性情绪的左半球优势使得研究者 认识到单一系统加工所有情绪的不合理性(Murphy, Nimmo-Smith, & Lawrence, 2003),于是双系统和多系 统模型应运而生。在这次思维的转向中,愤怒的特殊 性还没有引起人们的广泛关注。 2.2. 情绪加工的双系统模型 (Dual-System Models) 到了 20 世纪末,一些以人和动物为被试的研究 (Kalin, Larson, Shelton, & Davidson, 1998; Robinson & Manes, 2000)支 持了正性 情绪 和负性情 绪加 工相分 离 的假说。Davidson(1984)的效价不对称模型(valence asymmetry model)和动机模型(Cardinal, Parkinson, Hall, & Everitt, 2002)开始受到关注。前者认为大脑左 右半球分别与正性和负性情绪的加工有关;后者则认 为趋近动机激发并引导行为指向正性的刺激,回避动 机激发并指导行为指向负性刺激(Elliot, 2006),因此, 趋近系统易化了欲求行为,产生与之相关的正性情 绪,而回避系统易化了逃避行为,产生与之相关的负 性情绪(Davidson & Irwin, 1999)。 虽然有学者将正负效价分别与趋避动机相对应 (Mendoza & Ruys, 2001),但很多研究发现愤怒是一种 负性情绪但却与趋近动机有关(Carver & Harmon- Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 135  愤怒的加工机制 Jones, 2009; Mayan & Meiran, 2011; Stewart et al., 2010),这些发现挑战了效价假说,并使得动机假说成 为一种广受关注的对情绪加工机制的解释(邹吉林,张 小聪,张环,于靓,周仁来,2011)。 2.3. 情绪加工的多系统模型 (Multi-System Models) Ekman(1999)指出,神经科学的一个重要目标是 确定每种情绪的独特的中枢神经系统活动模式。在此 思想的指导下,研究者采用神经成像的手段发现不同 情绪类别的加工脑区确实有很大不同。当前研究已经 发现,某些脑区是特定情绪加工的核心结构,但是除 了愤怒体验和愤怒知觉的偏侧化现象比较明显之外, 大部分情绪加工没有明显的偏侧化现象(见表 1)。这提 示我们,一方面,需要重新审视偏侧化与情绪加工的 关系;另一方面,从偏侧化的角度探索愤怒的加工机 制,可能仍然是一个可行的方向。 3. 愤怒与动机的关系 3.1. 愤怒、动机与EEG 的偏侧化 虽然大部分研究认为愤怒是一种与趋近动机有 关的负性情绪(Carver & Har mon-Jones, 2009 ),但是作 此定论还为时尚早。首先,趋避动机的偏侧化是不 Table 1. The main brain areas re l a t e d to emotion processing 表1. 情绪加工的主要脑区,修改自(Lindquist et al., 2011) 情绪 类型 脑区 愤怒 体验 左侧脑岛前部、左侧外侧眶额皮层、左侧腹外侧前额 叶、左侧颞极 愤怒 知觉 左侧腹外侧前额叶、右侧内嗅皮层、右侧背外侧前额 叶、右侧纹状体旁区、右侧枕颞区、右侧辅助运动区 厌恶 体验 左侧杏仁核、右侧杏仁核、左侧内嗅皮层、右侧外侧 眶额皮层、左侧枕颞区 厌恶 知觉 右侧外侧眶额皮层、右侧脑岛前部、扣带回中前部、 左侧腹外侧前额叶、右侧腹外侧前额叶、右侧纹状体 旁区、右侧枕颞区 恐惧 体验 导水管周围灰质、右侧纹状体旁区、右侧枕颞区、左 侧颞中回 恐惧 知觉 左侧杏仁核、左侧内嗅皮层、右侧内嗅皮层、左侧海 马、右侧颞中回 高兴 体验 左侧纹状体旁区 悲伤 体验 左侧内嗅皮层、背内侧前额叶、右侧颞中回、右侧壳 核、导水管周围灰质 对称的。大量脑电(electroencephalography, EEG)研究 表明,趋近动机与大脑左半球的活动有关,而回避动 机没有明显的偏侧化现象(Coan & Allen, 2003; Nash, McGregor, & Inzlicht, 2010; Rutherford & Lindell, 2011)。其次,愤怒的偏侧化尚无定论。早期研究大多 认为愤怒与左侧额叶活动增强有关,如(Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1998)发现特质性愤怒个体左侧额叶在静息 状态下的活动更强,右侧额叶的基线活动更弱。但是 最近研究发现,在某些情况下(比如愤怒内投)愤怒会 伴随着右侧额叶的活动增强(Balconi & Mazza, 2010; Stewart et al., 2010; Zinner et al., 2008)。因此,单纯的 EEG 偏侧化不能作为愤怒与趋近动机相关的有力证 据。 3.2. 愤怒表达与愤怒特异性 有研究者提出愤怒表达(Zinner et al., 2008)和愤 怒特异性(Watson, 2009)的观点来解释愤怒与趋避动 机的不稳定联结。前者认为,愤怒的外投和内投分别 与趋近和回避动机相关;后者则认为愤怒的特异性成 分和非特异性成分分别与趋近和回避动机相关。 许多研究发现,即使在不需愤怒表达的情境下, 愤怒仍然会与动机产生联系。比如,Beaver 等(Beaver, Lawrence, Passamonti, & Calder, 2008)给被试呈现愤 怒、悲伤、中性面孔的图片,要求其完成性别判断任 务,接受磁共振扫描后完成行为抑制/趋近系统 (Behavioral Inhibition/Activation System, BIS/BAS)量 表。结果发现行为趋近系统的水平能够预测愤怒脑区 的激活。(Mayan & Meiran, 2011)以被试身体对“趋近” 和“远离”两类词的反应时为指标,检测了愤怒、焦 虑和控制组三组被试的动机指向。他们发现,焦虑组 和控制组对趋近词和回避词的反应时没有差异,而愤 怒组对趋近词的反应比对回避词的反应更快。这些研 究都发现在自然状态下愤怒会与趋近动机产生联系, 而不需做出内投或外投的表达,由此表明愤怒表达的 观点对愤怒与趋近动机的关系做了过窄的限定。 对于后者而言,Watson 提出的愤怒的一般性成分 和特异性成分往往很难区分,对于任何愤怒–趋近动 机的联结都可以根据这种观点将之定义为愤怒的特 异性成分,反之,对于任何愤怒–回避动机的联结都 可以定义为愤怒的一般性成分,导致该观点无法证伪。 Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 136  愤怒的加工机制 4. 情景化的愤怒和动机 大量事实表明,通过简单分类的方法界定愤怒与 动机的关系是非常困难的。愤怒的发生具有很强的情 境性(Harmon-Jones & Peterson, 2009),与动机和行为 有密切的关联。早在 2000年,Martin等(Martin , Watson, & Wan, 2000)就通过问卷法区分出特质性愤怒的三个 维度。他们用验证性因素分析(confirmatory factor analyses)分离出情感、行为和认知三个因素,也称为 ABC(affect, behavior, cognition)模型。由于认知和行为 都是对环境变化作出的适应性反应,因此,有必要考 虑具体情境下愤怒的加工机制,从进化到文化再到具 体情境,深入了解愤怒和动机加工的情境性特征。 4.1. 进化的影响 从进化角度讲,愤怒情绪具有威慑的作用,有利 于个体利益的维护;同时,生存适应造就了愤怒与攻 击性的自然联结(Wilkowski & Robinson, 2012),由于 攻击性是一种趋近反应,这就使得愤怒和趋近动机具 有了天然的联系。但个体选择战斗还是逃跑,取决于 对双方实力强弱的判断,并由行为激活/抑制系统决定 愤怒的实际表达是外投(攻击)还是内投(回避)(Kim & Lee, 2011)。愤怒与趋避动机的联结取决于行为激活/ 抑制系统的中介作用(Zinner et al., 2008)。 基于上述愤怒发生的生态观点,我们认为,愤怒 是通过对特定情境的认知引发的,然后评估行为表达 会对自身造成的利弊后果,由行为激活/抑制系统确定 动机取向,并进一步决定行为,最终实现对情境的适 应,维护自身利益。在这一过程中,决策会受到多方 面因素的影响,比如双方实力强弱、情绪状态及冲动 性等。 依赖于情境的决策过程充当了愤怒和动机的中 介,使得二者不必产生直接的联系,因而使愤怒与动 机的关系具有了一定的灵活性。愤怒产生后起到一个 威慑对方的作用,个体会作出进攻的准备,因此愤怒 首先与趋近动机产生即时联结,但经过对情境的评 估,行为抑制系统可能占优势,愤怒–趋近动机的联 结也转化为愤怒–回避动机的联结。在一般情境下, 愤怒总是先与趋近动机联结,但是在习得性无助的情 况下,愤怒可能优先与回避动机产生联结,这一预测 需要进一步验证。 4.2. 文化的影响 从达尔文时代起,研究者就认为情绪的面部表达 具有跨文化的一致性,即在不同的文化中人们是用相 同的面部活动来表达同一种情绪的(Ekman, Sorenson, & Friesen, 1969; Susskind, Lee, Cusi, Feiman, Grabski et al., 2008)。但最近的研究发现,西方文化中的被试 对表情的知觉依赖于眼睛、鼻子和嘴部的综合信息, 而东方文化中的被试对表情的知觉主要依赖于对眼 睛的观察,并且他们在区分恐惧和厌恶的表情时存在 困难(Jack, Blais, Scheepers, Schyns, & Caldara, 2009)。 虽然眼睛在表达情绪时存在很大的模糊性,但是对东 方人来说,面部肌肉在表达情绪时可能存在更大的模 糊性。Jack 等(Jack, Garrod, Yu, Caldara, & Schyns, 2012)在最新的研究中发现,西方白种人在表达六种基 本情绪时使用了各不相同的面部肌肉系统,而东亚人 群在表达情绪时使用的肌肉群有很大的重复性,尤其 在表达惊奇、恐惧、厌恶和愤怒的时候。这种文化差 异仅仅体现在对情绪的知觉上,而对平静面孔的知觉 则没有影响(Marsh, Elfenbein, & Ambady, 2003)。 虽然文化对表情知觉有影响,但是这种文化差异 产生的原因还不清楚。一些跨文化研究表明,这种差 异可能与不同文化人群的情境依赖性有关(Masuda, Ellsworth, Mesquita, Leu, Tanida et al., 2008),而杏仁核 的选择性激活对这种文化差异有所贡献(Chiao, Iidaka, Gordon, Nogawa, Bar et al., 2008)。最近的研究发现, 互依型文化(interdependent culture,如中国)和独立型 文化(independent culture,如德国)中的被试对愤怒共 情的神经表达是由不同的大脑区域调节的,但这些脑 区与动机系统具有何种联系尚不清楚。文化会对愤怒 和动机造成哪些影响?这些影响是如何产生的?对 于这些问题尚没有系统的研究。表情作为情绪表达的 窗口,受到了强烈的文化倾向的影响,最近的研究也 暗示了这种影响可能是深层次的,那么,文化必然以 某种方式参与到愤怒和动机的加工中来。将来的研究 需要采用行为和神经成像、遗传学研究等多种手段揭 示愤怒和动机的文化差异的原因。 4.3. 身体的影响 如前文所述,很多研究发现了愤怒和左侧额叶活 动水平之间的关系,但有一些功能磁共振成像 Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 137  愤怒的加工机制 (functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI)研究没 有发现二者之间的相关性(Tomarken & Zald, 200 9)。有 学者指出,这种相关性的缺失可能跟 fMRI 扫描时采 取的仰卧姿势有关。Harmon-Jones 和Peterson(2009) 对此假设进行了检验。他们先让被试写一段关于争议 话题的短文,此时被试或采取在椅子上竖直坐立的姿 势,或采取后仰的姿势。随后,给后仰的被试和一半 直立坐立的被试提供侮辱性反馈,而给另一半直立坐 立的被试提供中性反馈。结果发现直立–侮辱反馈组 被试与直立–中性反馈组被试相比,左侧额叶的活动 水平更高;而直立–侮辱反馈组被试与仰卧、侮辱反 馈组被试相比,也表现出更高水平的左侧额叶活动, 从而证明后仰姿势减弱了趋近动机。随后,Harmon- Jones 等(Harmon-Jones, Gable, & Price, 2011; Price & Harmon-Jones, 2011)又发现左侧额叶的活动水平从后 仰、直立到前倾依次增强,并且前倾的姿势能明显促 进趋近动机。这些研究充分表明身体情境对趋近动机 有着明显的影响,但是对愤怒的影响却没有出现一致 性的变化,这暗示了愤怒与趋近动机的变化并不总是 同步的,愤怒的加工可能受到更多因素的影响。未来 的研究需要进一步确定愤怒和动机在身体情境下的 关系及其影响因素。 此外,由于动机是行为激发和导向的原动力,趋 近–回避动机与可观察的身体活动是一致的(Elliot & Thrash, 2002),但这并不是说单纯通过身体活动就可 以确定愤怒与动机的关系。由于趋近动机系统可能是 左侧单侧化的,而回避动机系统可能是双侧分布的 (Spielberg et al., 2011),使得我们不能武断地把愤怒的 左侧偏侧化现象跟趋近动机对应起来。 总之,对愤怒与动机关系的界定要依赖于情境, 并确立明显的行为指标。情境在情绪加工中发挥着举 足轻重的作用,个体可以通过情绪感染来模仿愤怒表 达(Hareli, & Rafaeli, 2008)或者由对间接情境的认识 而引起愤怒(Forgas & George, 2001)。根据镜像神经元 (mirror neuron)和具身认知(embodied cognition)的相关 理论(Cattaneo & Rizzolatti, 2009; Iacoboni, 2009; Price, Peterson, & Harmon-Jones, 2012),除了与自己有关的 即时发生的事件,在生存经验及共情的作用下,特定 的刺激(如记忆中的事件、有愤怒表 情的图 片 等)也会 诱发愤怒情绪;这使得我们可以知觉和体验别人的愤 怒情绪,并做出相应的回应。愤怒的发生具有适应性 基础,通过认知和行为与情境发生作用,它与动机的 关系也受制于情境。因此,对愤怒与动机之间关系的 研究必须强调它们的关系是在什么情境下发生的,也 必须关注在动态的现实情境中二者的关系是怎样的 以及产生这种关系的原因是什么,这样才能更好地理 解愤怒的动机属性。 5. 总结与展望 愤怒的加工机制,尤其是愤怒与动机的关系是情 绪研究中的热点问题。虽然多数研究支持愤怒是一种 趋近动机取向的情绪(Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009), 但近年来越来越多的发现表明愤怒也可能跟回避动 机有关(Fetterman, Robinson, Gordon, & Elliot, 2011; Stewart et al., 2010; Watson, 2009; Zinner et al., 2008)。 对此,一些研究者提出愤怒表达(Zinner et al., 2008)和 愤怒特异性(Watson, 2009)的观点来解释这些新发现, 但这些针对某些特殊现象的观点不能很好地解释一 般的愤怒加工机制。为此,我们在 ABC 模型的基础 上尝试提出一个基于情境的动机模型,将愤怒的加工 机制放在特定的情境中来解释:愤怒以认知和行为为 中介与情境发生联系,对愤怒与动机关系的界定依赖 于对特定情境的评估,并由行为激活/抑制系统所决 定。这一模型能够解释当前愤怒与动机的主要发现, 并包含了从愤怒的发生到表达的整个过程,但其合理 性需要进一步验证。未来研究中还有诸多问题需要解 决,比如: 1) 需要设计更精致的实验来检验愤怒与动机的 关系。一方面,基于情境的动机解释只是在适应性框 架下对愤怒与动机关系的一个假设,对情境的评估能 否有效影响愤怒与动机的关系还需要实验检验。另一 方面,愤怒与动机的关系即使在同一次实验中也可能 不是固定不变的,在愤怒加工的时间进程中与环境的 信息交流可能改变愤怒与动机的对应关系,这一点也 需要实验研究来检验。 2) 从愤怒加工的激活脑区来看,似乎知觉–体验 二分法就能很好地说明愤怒的加工机制,但由于知觉 –体验的共生关系,对愤怒的知觉不可能不伴随愤怒 体验,对愤怒的体验也不可能独立于知觉加工,将它 们分开存在很大困难;反之,从整合的角度考虑更符 合系统的、进化的观点(Bassett & Gazzaniga, 2011)。 因此,在具体情境中,从时间和空间维度描述愤怒加 Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 138  愤怒的加工机制 工过程中的信息流动,建立愤怒加工的网络模型能够 更好地阐释愤怒加工的机制。 3) 趋避动机的加工回路尚未得到明确定义。虽然 有研究初步探讨了趋避动机的脑机制(Pizzagalli, Sherwood, Henriques, & Davidson, 2005),但加工过程 中皮层及亚皮层之间的连接及信息流向尚不清楚 (Harmon-Jones, Gable, & Peterson, 2010)。因此有必要 采用适当的神经成像技术揭示动机加工的动态过程。 对动机的动态加工机制的了解必然会促进对愤怒与 动机关系的认识。 4) 模块化是当前认知神经科学领域的重要探索 方向(Meunier, Lambiotte, & Bullmore, 2010),多系统 模型也表明许多情绪类别可能具有模块化特征。虽然 大脑功能的偏侧化有着重要的适应意义,并且在情绪 和动机的加工中起到重要作用(Harmon-Jones, Gable, & Peterson, 2010; Herrington, Heller, Mohanty, Engels, Banich et al., 2010);但是多数情绪类别及回避动机都 没有表现出明确的偏侧化,从模块化的角度理解情绪 与动机的加工机制将与情感神经科学的发现更加吻 合。因此,模块化的观点可能成为未来对情绪及动机 的神经机制的主要解释。探索情绪与动机的模块化特 点将有力地促进人们对二者的理解。 总之,愤怒是一种基本的负性情绪,它已经内化 到人类的基因之中(Reuter, Weber, Fiebach, Elger, & Montag, 2009),并且与心脏病 (Chida & S tept oe, 2 00 9; Taggart, Boyett, Logantha, & Lambiase, 2011)、焦虑和 抑郁(Newman & Llera, 2011; Rutherford & Lindell, 2011)等身心疾病有着密切的联系。同时,它作为一种 特殊的负性情绪对当前的情绪分类构成了挑战。愤怒 的加工机制,尤其是它在不同情境下与动机之间的复 杂关系成为亟待解决的重要问题。愤怒的加工机制的 复杂性可能恰恰反映了它在进化中具有非常重要的 作用。在社会化背景下,个体要维护地位和尊严,获 得繁殖与发展的机会,必然要用到愤怒这一有力的武 器。因此,愤怒的价值只有在社会背景中,与地位、 自尊、目标、奖惩等一系列因素结合起来才能得到充 分的体现。 参考文献 (References) 邹吉林, 张小聪, 张环, 于靓, 周仁来(2011). 超越效价和唤醒—— 情绪的动机维度模型述评. 心理科学进展, 9期, 1339-1346. Adolphs, R., Russell, J. A., & Tranel, D. (1999). A role for the human amygdala in recognizing emotional arousal from unpleasant stimuli. Psychological Science, 10, 167-171. Balconi, M., & Mazza, G. (2010). Lateralisation effect in comprehen- sion of emotional facial expression: A comparison between EEG al- pha band power and behavioural inhibition (BIS) and activation (BAS) systems. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cogni- tion, 15, 361-384. Bassett, D. S., & Gazzaniga, M. S. (2011). Understanding complexity in the human brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15, 200-209. Beaver, J. D., Lawrence, A. D., Passamonti, L., & Calder, A. J. (2008). Appetitive motivation predicts the neural response to facial signals of aggression. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 2719-2725. Borod, J. C., Zgaljardic, D., Tabert, M. H., & Koff, E. (2001). Asym- metries of emotional perception and expression in normal adults. In G. Gainotti (Ed.), Handbookof neuropsychology (Vol. 5, pp. 181- 205). Am sterdam: Elsevier . Calder, A. J., Lawrence, A. D., & Young, A. W. (2001). Neuropsychol- ogy of fear and lo athing. Nature Reviews Ne uroscience, 2, 352-363. Cardinal, R. N., Parkinson, J. A., Hall, J., & Everitt, B. J. (2002). Emo- tion and motivation: The role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 26, 321-352. Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-re- lated affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 183-204. Cattaneo, L., & Rizzolatti, G. (2009). The mirror neuron system. Ar- chives of Neurol ogy, 66, 557-560. Chiao, J. Y., Iidaka, T., Gordon, H. L., Nogawa, J., Bar, M., Aminoff, E., Sadato, N., & Ambady, N. (2008). Cultural specificity in amyg- dala response to fear faces. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 2167-2174. Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2009). The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review of pro- spective evidence. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 53, 936-946. Coan, J. A., & Allen, J. J. B. (2003). Frontal EEG asymmetry and the behavioral activation and inhibition systems. Psychophysiology, 40, 106-114. Davidson, R. J. (1984). Affect, cognition and hemispheric specializa- tion. In C. E. Izard, J. Kagan, & R. Zajonc (Eds.), Emotion, cogni- tion and behavior (pp. 320-365). New York: Cambridge University Press. Davidson, R. J., & Irwin, W. (1999). The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3, 11-21. Davidson, R. J., Shackman, A. J., & Maxwell, J. S. (2004). Asymme- tries in face and brain related to emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sci- ences, 8, 389-391. Ekman, P. (1999). Basic emotions. In T. Dalgleish, & M. J. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 45-60). Chichester: Wiley. Ekman, P., Sorenson, E. R., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of emot i on. Science, 164, 86-88. Elliot, A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 111-116. Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804-818. Fetterman, A. K., Robinson, M. D., Gordon, R. D., & Elliot, A. J. (2011). Anger as seeing red: Perceptual sources of evidence. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 311-316. Forgas, J. P., & George, J. M. (2001). Affective influences on judg- ments and behavior in organizations: An information processing perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Proc- esses, 86, 3-34. Hareli, S., & Rafaeli, A. (2008). Emotion cycles: On the social influ- ence of emotion in organizations. Research in Organizational Be- havior, 28, 35-39. Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. J. B. (1998). Anger and frontal brain Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 139  愤怒的加工机制 Copyright © 2012 Hanspub 140 activity: EEG asymmetry consistent with approach motivation de- spite negative affective valence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1310-1316. Harmon-Jones, E., Gable, P. A., & Peterson, C. K. (2010). The role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in emotion-related phenomena: A review and update. Biological Psychology, 84, 451-462. Harmon-Jones, E., Gable, P. A., & Price, T. F. (2011). Leaning embod- ies desire: Evidence that leaning forward increases relative left fron- tal cortical activation to appetitive stimuli. Biological Psychology, 87, 311-313. Harmon-Jones, E., & Peterson, C. K. (2009). Supine body position reduces neural response to anger evocation. Psychological Science, 20, 1209-1210. Harmon-Jones, E., Peterson, C. K., & Harmon-Jones, C. (2010). Anger, motivation, and asymmetrical frontal cortical activations. In M. Po- tegal, G. Stemmler, & C. Spielberger (Eds.), International handbook of anger: Constituent and concomitant biological, psychological, and social processes (pp. 61-78). New York: Springer. Herrington, J. D., Heller, W., Mohanty, A., Engels, A. S., Banich, M. T., Webb, A. G., & Miller, G. A. (2010). Localization of asymmetric brain function in emotion and depression. Psychophysiology, 47, 442-454. Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 653-670. Jack, R. E., Blais, C., Scheepers, C., Schyns, P. G., & Caldara, R. (2009). Cultural confusions show that facial expressions are not universal. Current Biology, 19, 1543-1548. Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G. B., Yu, H., Caldara, R., & Schyns, P. G. (2012). Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in press. Kalin, N. H., Larson, C., Shelton, S. E., & Davidson, R. J. (1998). Asymmetric frontal brain activity, cortisol, and behavior associated with fearful temperament in rhesus monkeys. Behavioral Neurosci- ence, 112, 286-2892. Kim, D.-Y., & Lee, J.-H. (2011). Effects of the BAS and BIS on deci- sion-making in a gambling task. Personality and Individual Differ- ences, 50, 1131-1135. Lindquist, K. A., Wager, T. D., Kober, H., Bliss-Moreau, E., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 173, 1-86. MacLean, P. D. (1993). Cerebral evolution of emotion. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 67-83). New York: Guilford. Marsh, A. A., Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, N. (2003). Nonverbal “ac- cents” cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. Psycho- logical Science, 14, 373-376. Martin, R., Watson, D., & Wan, C. K. (2000). A three-factor model of trait anger: Dimensions of affect, behavior, and cognition. Journal of Personality, 68, 869-897. Masuda, T. , Ellsworth, P. C., Mesquita, B., Leu, J., Tanida, S., & Veer- donk, E. V. D. (2008). Placing the face in context: Cultural differ- ences in the perception of facial emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 365-381. Mayan, I., & Meiran, N. (2011). Anger and the speed of full-body approach and avoidance reactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 1-7. Mendoza, S. P., & Ruys, J. D. (2001). The beginning of an alternative view of the n eurobiology of emotion. Social Scien ce Information, 40, 39-60. Meunier, D., Lambiotte, R., & Bullmore, E. T. (2010). Modular and hierarchically modular organization of brain networks. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 4, 200. Murphy, F. C., Nimmo-Smith, I., & Lawrence, A. D. (2003). Func- tional neuroanatomy of emotions: A meta-analysis. Cognitive, Affec- tive, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 3, 207-233. Nash, K., McGregor, I., & Inzlicht, M. (2010). Line bisection as a neural marker of approach motivation. Psychophysiology, 47, 979- 983. Newman, M. G., & Llera, S. J. (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a contrast avoidance model of worry. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 371-382. Pizzagalli, D. A., Sherwood, R. J., Henriques, J. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2005). Frontal brain asymmetry and reward responsiveness: A source-localization study. Psychological Science, 16, 805-813. Price, T. F., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2011). Approach motivational body post ures lean toward left frontal brain activity. Psychophysiology, 48, 718-722. Price, T. F., Peterson, C. K., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2012). The emotive neuroscience of embodiment. Motivation and Emotion, 36, 27-37. Reuter, M., Weber, B., Fiebach, C. J., Elger, C., & Montag, C. (2009). The biological basis of anger: Associations with the gene coding for DARPP-32 (PPP1R1B) and with amygdala volume. Behavioural Brain Research, 202, 179-183. Robinson, R. G., & Manes, F. (2000). Elation, mania, and mood disor- ders: Evidence from neurological disease. In J. C. Borod (Ed.), The neuropsychology of emotion (pp. 239-268). Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. Rohlfs, P., & Ramírez, M. (2006). Aggression and brain asymmetries: A theoretical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11, 283-297. Rutherford, H. J. V., & Lindell, A. K. (2011). Thriving and surviving: Approach and avoidance motivation and lateralization. Emotion Re- view, 3, 333-343. Sackeim, H. A., Gur, R. C., & Saucy, M. C. (1978). Emotions are ex- pressed more intensely on the left side of the face. Science, 202, 434-436. Spielberger, C. D., Reheiser, E. C., & Sydeman, S. J. (1995). Measur- ing the experience, expression, and control of anger. In H. Kassinove (Ed.), Anger disorders: Definition, diagnosis, and treatment (pp. 49-67). Phila delphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. Stewart, J. L., Silton, R. L., Sass, S . M., Fisher, J. E., Edgar, C., Heller, W., & Miller, G. A. (2010). Attentional bias to negative emotion as a function of approach and withdrawal anger styles: An ERP investi- gation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 76, 9-18. Susskind, J. M., Lee, D. H., Cusi, A., Feiman, R., Grabski, W., & Anderson, A. K. (2008). Expressing fear enhances sensory acquisi- tion. Nature N euroscience, 11, 843-850. Taggart, P., Boyett, M. R., Logantha, S., & Lambiase, P. D. (2011). Anger, emotion, and arrhythmias: From brain to heart. Frontiers in Physiology, 2, 67. Tomarken, A. J., & Zald, D. H. (2009). Conceptual, methodological, and empirical ambiguities in the linkage between anger and ap- proach: Comment on Carver and Harmon-Jones. Psychological Bul- letin, 135, 209-214. Videbeck, S. L. (2010). Psychiatric-mental health nursing (4 Edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Watson, D. (2009). Locating anger in the hierarchical structure of affect: Comment on Carver and Harmon-Jones. Psychological Bul- letin, 135, 205-208. Wilkowski, B. M., & Robinson, M. D. (2012). When aggressive indi- viduals see the world more accurately: The case of perceptual sensi- tivity to subtle facial expressions of anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 540-553. Zinner, L. R., Brodish, A. B., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2008). Anger and asymmetrical frontal cortical activity: Evidence for an anger—Withdrawal relationship. Cognition & Emotion, 22, 1081-1093. |