Hans Journal of Agricultural Sciences

Vol.06 No.06(2016), Article ID:19225,8

pages

10.12677/HJAS.2016.66030

Advances in Research on the Composition of Dietary Fiber in Fruits

Qi Zhang1,2, Min Lu2*

1Kiwifruit Industry Development Bureau of Xiuwen County, Guiyang Guizhou

2Agricultural College, Guizhou University, Guiyang Guizhou

Received: Nov. 27th, 2016; accepted: Dec. 12th, 2016; published: Dec. 15th, 2016

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

ABSTRACT

Dietary fibre means carbohydrate polymers which are not hydrolyzed by the endogenous enzymes in the small intestine of humans, including cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, pectin, resistant starch and oligosaccharide, which was divided into two types as soluble dietary fiber and insoluble dietary fiber according to the solubility. This article summarizes the “high fiber”, “fiber source” fruit and high quality dietary fiber. The research progress of dietary fiber composition in fruits was reviewed from the aspects of oligosaccharides, resistant starch and cell wall component. The monosaccharide composition of total dietary fiber, soluble dietary fiber and insoluble dietary fiber was also reviewed.

Keywords:Fruits, Dietary Fibre, Monosaccharide Composition, Oligosaccharide, Cell Wall Component

果实膳食纤维组成研究进展

张起1,2,鲁敏2*

1修文县猕猴桃产业发展局,贵州 贵阳

2贵州大学农学院,贵州 贵阳

收稿日期:2016年11月27日;录用日期:2016年12月12日;发布日期:2016年12月15日

摘 要

膳食纤维指抗人体小肠消化吸收,但在大肠中能部分或全部发酵的可食用植物性成分——碳水化合物及类似物质,包括纤维素、半纤维素、木质素、果胶、抗性淀粉、寡糖等,按溶解性分为可溶性膳食纤维和不溶性膳食纤维两类。本文综述了“高纤维”、“纤维源”果品及高品质膳食纤维,从寡糖、抗性淀粉及细胞壁组分等方面综述了果实膳食纤维组成的研究进展,并进一步挖掘了果实总膳食纤维、可溶性膳食纤维和不溶性膳食纤维的单糖组成。

关键词 :果实,膳食纤维,单糖组成,寡糖,细胞壁组分

1. 引言

自Hipsley [1] 初步认定膳食纤维是“纤维素、半纤维素和木质素”以来,历经半个多世纪的发展,虽然其间一直争议不断,但膳食纤维的内涵始终得到补充和完善,目前国内外普遍认同的膳食纤维定义为:“抗人体小肠消化吸收,但在大肠中能部分或全部发酵的可食用植物性成分——碳水化合物及类似物质,包括纤维素、半纤维素、木质素、果胶、抗性淀粉、寡糖等” [2] [3] 。作为人体“第七大营养素”,膳食纤维具有改善肠道功能,调节血糖及血糖耐受度,降低血液胆固醇等多种健康效应 [4] [5] [6] 。

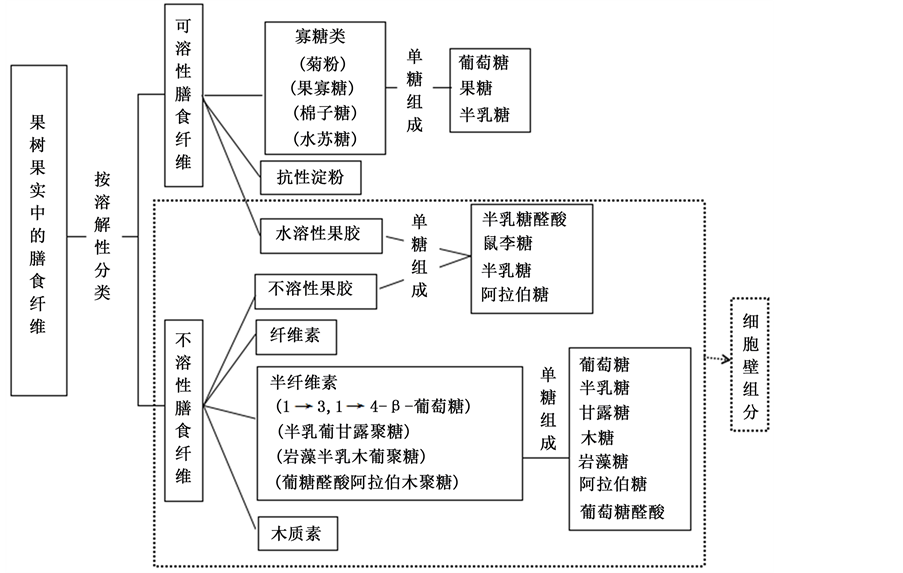

果树果实是人类摄取膳食纤维的重要途径之一。按溶解性可将果树果实总膳食纤维(TDF)分为两类:可溶性膳食纤维(SDF)和不溶性膳食纤维(IDF),可溶性膳食纤维包括寡糖类、抗性淀粉以及水溶性果胶;不溶性膳食纤维包含不溶性果胶、纤维素、半纤维和木质素,具体如图1所示。而果实发育及贮藏过程中纤维素、半纤维素、木质素及果胶等细胞壁组分的变化是引起果实膳食纤维组成改变的主要因素,因此,果实膳食纤维组分的研究很大程度得益于研究者们对于植物细胞壁代谢的关注 [7] ,为方便总结叙述,文中将细胞壁组分水溶性果胶列入不溶性膳食纤维进行描述。

2. 总膳食纤维(TDF)

2.1. “高纤维”和“纤维源”果实

按照欧盟委员会标准,食品中膳食纤维含量超过3%可认为是“纤维源”食品,超过6%即可认定为“高纤维”食品 [8] 。“高纤维”鲜果如人心果(Achras sapota, 10.9%) [9] 、番石榴(Psidium guajava, 8.5%) [9] 、余甘子(Phyllanthus emblica, 7.3%) [9] 、木橘(Aegle marmelos, 6.40%) [10] ,西梅(6%~7%) [11] ;干果如板栗(Castanea sativa, 13.7%) [12] ,“纤维源”鲜果如番荔枝(Anona squamosa, 5.5%) [9] 、无花果(Ficus carica, 5.0%) [9] 、刺梨(Rosa roxburghii, 4.2%) [13] 、酸枣(Zizyphus jujube, 3.8%) [9] 、蒲桃(Syzygium cumini, 3.5%) [9] 、树菠萝(Artocarpus heterophyllus, 3.5%) [9] 等。

芒果鲜果属“高纤维”食品,四种芒果果肉的膳食纤维的含量:“金芒果”(23.07%) > “凯特芒”(9.69%) > “大金煌芒”(7.78%) > “吕宋芒”(6.54%) [14] [15] ;另有一种野生芒果Mangifera pajang总膳食纤维含量达到了鲜重的83.50% [16] 。海枣(Phoenix dactylifera)也是膳食纤维含量较高的果实,但不同品种差异较大,每100 g干质量果实中TDF含量从7.81~93.46不等 [17] [18] [19] [20] 。“Manzanilla”

Figure 1. Composition of main dietary fibre in fruits

图1. 果树果实中膳食纤维的组成

和“Gordal”橄榄品种每100 g鲜果肉中TDF含量约5 g,为“纤维源”果品,而“Hojiblanca”中含量 > 6 g,为“高纤维”果品 [21] 。“长营”、“惠圆”、“自来圆”、“檀香”和“檀头”5个橄榄品种的果实TDF含量为37.40~50.36 g/hg DW,品种间差异显著,以“长营”和“自来圆”含量相对较高 [22] 。香蕉属“纤维源”果实,TDF含量为3.54%~5.08% [15] [23] 。

2.2. 单糖组成

不同种类果实TDF单糖组成差异较大。北方7种水果中检测到8种单糖,草莓、山楂、苹果、桃、杏以半乳糖醛酸为主,梨以阿拉伯糖为主,桑椹中半乳糖醛酸与阿拉糖含量相当 [24] 。木瓜(Chaenomeles speciosa)中含9种单糖,分别为鼠李糖、岩藻糖、阿拉伯糖、木糖、甘露糖、半乳糖、纤维素葡萄糖、非纤维素葡萄糖、半乳糖醛酸,9种单糖中以纤维素葡萄糖含量最高,每100 g TDF含纤维素葡萄糖28.6 g,其次为半乳糖醛酸25.3 g,岩藻糖含量最低,仅0.6 g。日本木瓜(Chaenomeles japonica)与木瓜单糖组成基本一致,只是“NV1944”、“NV1410”和“NV152”3种基因型半乳糖醛酸含量稍高于纤维素葡萄糖 [25] 。海枣果肉中含6种单糖,以葡萄糖含量最高(2 g/100g TDF),其次为木糖、半乳糖、阿拉伯糖,鼠李糖含量最低(0.06 g/100g TDF),中性糖含量(3.63 g/100g TDF)大于醛酸类含量(2.04 g/100g TDF) [17] 。芒果果肉中含4种单糖,以甘露糖含量最大(0.59%),其次是山梨糖、半乳糖、鼠李糖(0.07%) [14] 。

3. 可溶性膳食纤维(SDF)

3.1. 高品质膳食纤维

SDF含量是影响膳食纤维生理功能的重要因素,高品质膳食纤维应达到SDF含量 ≥ 10%的要求,SDF与IDF最佳比例为1:3 [26] 。如表1所示,结合Ramulu和Udayasekhara Rao [9] 对印度25种果实,

Table 1. SDF/IDF in ripen flesh of different fruit species (%)

表1. 不同种类果实成熟果肉中可溶性膳食纤维(SDF)含量(%)

吕明霞等 [24] 对北方7种水果的描述,除板栗和少数几种海枣、番石榴外,几乎所有果实都满足高品质膳食纤维的要求,其中SDF在芒果和苹果果实中最高可占到66.67%,山楂75.0%,桃86.3%。

3.2. 寡糖类和抗性淀粉

火龙果新鲜果肉中含有寡糖类约90 g/kg [42] 。草莓中也含微量寡糖,分别为:蔗果三糖(40 µg/g FW),新科斯糖(10 µg/g FW),蔗果四糖(5 µg/g FW),kestopentaose (菊粉的一种,3 µg/g FW) [43] 。杨桃和番橄榄中含有的微量果寡糖为蔗果三糖和蔗果四糖 [44] 。苹果果实中含有棉子糖和水苏糖,水苏糖随着果实发育降低,棉子糖较水苏糖含量低,但在果实发育过程中保持不变 [45] 。桃和猕猴桃中含有微量棉子糖 [46] [47] 。抗性淀粉主要存在于香蕉和板栗中,随着香蕉果实的发育,抗性淀粉含量呈直线上升趋势,断蕾后50 d,抗性淀粉含量达到最大值,为402.96 mg/g FW [48] 。生板栗中抗性淀粉含量为27.44%,占总淀粉的比例为68.93% [49] 。

3.3. 单糖组成

果实SDF单糖组成以醛酸类为主,不同种类果实在中性糖的组成上具有一定的特异性。北方7种水果SDF均以半乳糖醛酸为主 [24] 。木瓜(Chaenomeles speciosa)果实SDF含8种单糖,以半乳糖醛酸含量最高,每100 g SDF含71.6 g半乳糖醛酸,其次为阿拉伯糖9.9 g,甘露糖8.0 g,半乳糖4.7 g,鼠李糖2.2 g,葡萄糖1.5 g,木糖1.1 g,岩藻糖含量最低,仅0.3 g。日本木瓜(Chaenomeles japonica)与木瓜SDF单糖组成基本一致,区别之处在于葡萄糖与鼠李糖的含量,日本木瓜中葡萄糖含量较高,而木瓜中鼠李糖含量更高 [25] 。野生芒果Mangifera pajang SDF含8种单糖,依次为甘露糖(1.51%)、阿拉伯糖、葡萄糖、鼠李糖、赤藓糖(0.14%)、半乳糖、木糖、岩藻糖(0.01%),醛酸类含量(5.83%)大于中性糖含量(3.02%),赤藓糖是这种野生芒果单糖的独特组成 [15] 。海枣果肉中含6种单糖,以葡萄糖含量最高(0.41 g/100g SDF),鼠李糖含量最低(0.03 g/100g SDF),醛酸类含量(1.80 g/100g SDF)大于中性糖含量(0.84 g/100g SDF) [14] 。苹果SDF中含有6种单糖,以半乳糖醛酸含量最高(42.3%),其次为阿拉伯糖(25.7%),含量最低的为岩藻糖(1.9%),未检测到甘露糖和葡萄糖 [37] 。

4. 不溶性膳食纤维(IDF)

4.1. 细胞壁组分

柑橘类果实膳食纤维以果胶,尤其是水溶性果胶为主,其次为纤维素或原果胶,木质素含量最低;在柠檬、柚、椪柑、脐橙、温州蜜柑、胡柚五种果实中,果胶、水溶性果胶、纤维素和木质素以柠檬中含量最高,原果胶以温州蜜柑中含量最高 [28] 。菠萝中以纤维素为主,其次为半纤维素 [35] 。刺梨果实以纤维素为主,其次为半纤维素、原果胶、木质素,水溶性果胶含量最低 [13] 。海枣果实以木质素为主,其次为纤维素、半纤维素 [37] 。枇杷果实生长发育过程中,水溶性果胶含量呈上升趋势,离子结合果胶、共价结合果胶、纤维素、半纤维素呈下降趋势 [50] 。而梨果实生长过程中纤维素、半纤维素含量在整个生长周期中的变化无明显规律,木质素含量先增后减,水溶性果胶含量递增 [51] 。嘎拉苹果发育期共价结合果胶含量最高,纤维素含量远高于半纤维素,采后共价结合果胶快速降低,水溶性果胶含量开始增加,纤维素和半纤维素含量降低 [51] 。枣果实发育过程中,果皮中原果胶、纤维素含量降低,水溶性果胶含量增加 [53] 。

4.2. 单糖组成

果实IDF单糖组成以中性糖为主,大多以葡萄糖含量最高,不同种类果实间差异较大。北方7种水果中检测到8种单糖,草莓、山楂、苹果、桃、杏以半乳糖醛酸为主,梨以阿拉伯糖为主,桑椹中半乳糖醛酸与阿拉糖含量相当 [24] 。桃中的果胶多糖主要为半乳糖醛酸、半乳糖和阿拉伯糖,半纤维素多糖主要为木糖和半乳糖,纤维素多糖分主要为阿拉伯糖和半乳糖 [54] 。杏水溶性果胶的单糖组成主要为半乳糖醛酸,其次为半乳糖、阿拉伯糖、葡萄糖 [55] 。木瓜(Chaenomeles speciosa)中含9种单糖,其组成与含量变化趋势与TDF相同,其中纤维素葡萄糖含量最高,其次为半乳糖醛酸、木糖,含量最低的仍然为岩藻糖。日本木瓜与木瓜单糖组成基本一致,仅“NV1597”果实中木糖含量高于半乳糖醛酸含量 [25] 。海枣果肉中含6种单糖,以葡萄糖含量最高(1.57 g/100g IDF),鼠李糖含量最低(0.03 g/100g IDF),中性糖含量(3.02 g/100g TDF)远大于醛酸类含量(0.14 g/100g TDF) [14] 。野生芒果Mangifera pajang SDF含7种单糖,以阿拉伯糖含量为主(18.47%),其次为葡萄糖(4.46%)、甘露糖(3.15%),岩藻糖(0.01%)含量最低,中性糖含量(30.18%)约为醛酸类含量(15.51%)的2倍 [15] 。苹果IDF中含有8种单糖,以葡萄糖含量最高(33.5%),其次为半乳糖醛酸(27.1%)、阿拉伯糖(16.5%),含量最低的为岩藻糖(1.2%) [37] 。

5. 结语

膳食纤维作为一类生物活性物质对人体的健康起着重要的作用,既可促进健康又可预防疾病。膳食纤维组分的研究是进行膳食纤维改性技术研究及功能评价与应用的基础。如前所述,果实膳食纤维组分的研究很大程度得益于研究者们对于植物细胞壁代谢的关注,则关注点主要为纤维素、半纤维素、木质素、果胶等中高分子量膳食纤维,对于果实低分子量膳食纤维如寡糖类的研究还相对较少。今后果实膳食纤维的研究将在功能食品的开发,膳食纤维组分的积累与调控机制等方面得到长足发展。

基金项目

国家自然科学基金:刺梨果实膳食纤维组成、积累及其调控的分子生理基础(31660549)。

文章引用

张 起,鲁 敏. 果实膳食纤维组成研究进展

Advances in Research on the Composition of Dietary Fiber in Fruits[J]. 农业科学, 2016, 06(06): 194-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/HJAS.2016.66030

参考文献 (References)

- 1. Hipsley, E.H. (1953) Dietary “Fibre” and Pregnancy Toxaemia. British Medical Journal, 2, 420. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.4833.420

- 2. 李建文, 杨月欣. 膳食纤维定义及分析方法研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2007, 28(2): 350-355.

- 3. Zielinski, G. and Rozema, B. (2013) Review of Fiber Methods and Applicability to Fortified Foods and Supplements: Choosing the Correct Method and Interpreting Results. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 405, 4359-4372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-013-6711-x

- 4. Kendall, C.W., Esfahani, A. and Jenkins, D.J. (2010) The Link between Dietary Fibre and Human Health. Food Hydrocolloids, 24, 42-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.08.002

- 5. Brownlee, I.A. (2011) The Physiological Roles of Dietary Fibre. Food Hydrocolloids, 25, 238-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.11.013

- 6. 王晓梅, 木泰华, 李鹏高. 膳食纤维防治糖胖症及其并发症的研究进展[J]. 核农学报, 2013, 27(9): 1324-1330.

- 7. 赵云峰, 林瑜, 林河通. 细胞壁组分变化与果实成熟软化的关系研究进展[J]. 食品科技, 2012(12): 29-33.

- 8. European Commission (2006) Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Official Journal of the European Union, L404, 9-25.

- 9. Ramulu, P. and Udayasekhara Rao, P. (2003) Total, Insoluble and Soluble Dietary Fiber Contents of Indian Fruits. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 16, 677-685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00095-4

- 10. Charoensiddhi, S. and Anprung, P. (2008) Bioactive Compounds and Volatile Compounds of Thai Bael Fruit (Aegle Marmelos (L.) Correa) as a Valuable Source for Functional Food Ingredients. International Food Research Journal, 15, 1-9.

- 11. Fatimi, A., Ralet, M., Crepeau, M.J., Rashidi, S. and Thibault, J.-F. (2007) Dietary Fibre Content and Cell Wall Polysaccharides in Prunes. Sciences des Aliments, 27, 423-429. https://doi.org/10.3166/sda.27.423-430

- 12. Gonçalves, B., Borges, O., Costa, H.S., et al. (2010) Metabolite Composition of Chestnut (Castanea sativa, Mill.) upon Cooking: Proximate Analysis, Fibre, Organic Acids and Phenolics. Food Chemistry, 122, 154-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.02.032

- 13. 刘玉倩, 孙雅蕾, 鲁敏, 安华明. 刺梨果实中膳食纤维的组分与含量[J]. 营养学报, 2015(3): 303-305.

- 14. 陈多谋, 文攀, 杭瑜瑜, 等. 三种芒果果皮及果肉中膳食纤维的组分研究[J]. 食品研究与开发, 2016, 37(8): 9-14.

- 15. Arumugam, R. and Manikandan, M. (2011) Fermentation of Pretreated Hydrolyzates of Banana and Mango Fruit Wastes for Ethanol Production. Asian Journal of Experimental Biological Sciences, 2, 246-256.

- 16. Al-Sheraji, S.H., Ismail, A., Manap, M.Y., et al. (2011) Functional Properties and Characterization of Dietary Fiber from Mangifera pajang Kort. Fruit Pulp. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 59, 3980-3985. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf103956g

- 17. Elleuch, M., Besbes, S., Roiseux, O., et al. (2008) Date Flesh: Chemical Composition and Characteristics of the Dietary Fibre. Food Chemistry, 111, 676-682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.036

- 18. Borchani, C., Besbes, S., Masmoudi, M., et al. (2011) Effect of Drying Methods on Physico-Chemical and Antioxidant Properties of Date Fibre Concentrates. Food Chemistry, 125, 1194-1201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.10.030

- 19. Borchani, C., Besbes, S., Masmoudi, M., et al. (2011) Influence of Oven-Drying Temperature on Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Date Fibre Concentrates. Food & Bioprocess Technology, 5, 1541-1551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-011-0549-z

- 20. Elhoumaizi, A.H., Borchani, C., Attia, H., et al. (2012) Physicochemical Characterization and Associated Antioxidant Capacity of Fiber Concentrates from Moroccan Date Flesh. Indian Journal of Food Science and Technology, 5, 2954-2960.

- 21. Galanakis, C.M. (2011) Olive Fruit Dietary Fiber: Components, Recovery and Applications. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 22, 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2010.12.006

- 22. 欧高政, 陈清西. 橄榄果实膳食纤维含量及动态变化研究[J]. 福建农业学报, 2009, 24(1): 64-67.

- 23. Thaiphanit, S. and Anprung, P. (2010) Physicochemical and Flavor Changes of Fragrant Banana (Musa acuminata AAA Group “Gross Michel”) during Ripening. Journal of Food Processing & Preservation, 34, 366-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4549.2008.00314.x

- 24. 吕明霞, 李媛, 张飞, 等. 气相色谱法分析北方水果中膳食纤维的单糖组成[J]. 中国食品学报, 2012, 12(2): 213-218.

- 25. Thomas, M. and Thibault, J.F. (2003) Dietary Fibre and Cell-Wall Polysaccharides in Chaenomeles Fruits. Japanese Quince: Potential fruit crop for Northern Europe, 99-126.

- 26. 杨明华, 太周伟, 俞政全, 等. 膳食纤维改性技术研究进展[J]. 食品研究与开发, 2016, 37(10): 207-210.

- 27. Vegagálvez, A., Zurabravo, L., Lemusmondaca, R., et al. (2015) Influence of Drying Temperature on Dietary Fibre, Rehydration Properties, Texture and Microstructure of Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.). Journal of Food Science & Technology, 52, 1-8.

- 28. 祝渊, 陈力耕, 胡西琴. 柑橘果实膳食纤维的研究[J]. 果树学报, 2003, 20(4): 256-260.

- 29. Gorinstein, S., Haruenkit, R., Poovarodom, S., et al. (2009) The Comparative Characteristics of Snake and Kiwi Fruits. Food & Chemical Toxicology, 47, 1884-1891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.047

- 30. Park, Y.S., Leontowicz, H., Leontowicz, M., et al. (2011) Comparison of the Contents of Bioactive Compounds and the Level of Antioxidant Activity in Different Kiwifruit Cultivars. Journal of Food Composition & Analysis, 24, 963-970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2010.08.010

- 31. Haruenkit, R., Poovarodom, S., Leontowicz, H., et al. (2007) Comparative Study of Health Properties and Nutritional Value of Durian, Mangosteen, and Snake Fruit: Experiments in Vitro and in Vivo. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 55, 5842-5849. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf070475a

- 32. Kunnika, S. and Pranee, A. (2011) Influence of Enzyme Treatment on Bioactive Compounds and Colour Stability of Betacyanin in Flesh and Peel of Red Dragon Fruit Hylocereus polyrhizus (Weber) Britton and Rose. International Food Research Journal, 18, 1437-1448.

- 33. Aziz, N., Wong, L., Bhat, R. and Cheng, L. (2012) Evaluation of Processed Green and Ripe Mango Peel and Pulp Flours (Mangifera indica, var. Chokanan) in Terms of Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Compounds and Functional Properties. Journal of the Science of Food & Agriculture, 92, 557-563. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4606

- 34. Barroca, M.J., Guiné, R.P.F., Pinto, A., Gonçalves, F.M. and Ferreira, D.M.S. (2006) Chemical and Microbiological Characterization of Portuguese Varieties of Pears. Food & Bioproducts Processing, 84, 109-113. https://doi.org/10.1205/fbp.05200

- 35. 史俊燕, 张秀梅, 孙光明. 菠萝果实膳食纤维的研究[J]. 广东农业科学, 2010, 37(11): 110-111.

- 36. Bailoni, L., Schiavon, S., Pagnin, G., Tagliapietra, F. and Bonsembiante, M. (2005) Quanti-Qualitative Evaluation of Pectins in the Dietary Fibre of 24 Foods. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 4, 49-58. https://doi.org/10.4081/ijas.2005.49

- 37. Colin-Henrion, M., Mehinagic, E., Renard, C., Richomme, P. and Jourjon, F. (2009) From Apple to Applesauce: Processing Effects on Dietary Fibres and Cell Wall Polysaccharides. Food Chemistry, 117, 254-260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.03.109

- 38. Guiné, R., Sousa, R., Alves, A., et al. (2010) Phenolic, Dietetic Fibre and Sensorial Analyses of Apples from Regional Varieties Produced in Conventional and Biological Mode. Agricultural Engineering International, 12, 70-78.

- 39. Jiménezescrig, A., Rincón, M., Pulido, R. and Saura-Calixto, F. (2001) Guava Fruit (Psidium guajava L.) as a New Source of Antioxidant Dietary Fiber. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry, 49, 5489-5493. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf010147p

- 40. Anprung, P. and Sangthawan, S. (2012) Prebiotic Activity and Bioactive Compounds of the Enzymatically Depolymerized Thailand-Grown Mangosteen Aril. Journal of Food Research, 1, 268-276. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v1n1p268

- 41. Kosmala, M., Milala, J., Kolodziejczyk, K., et al. (2013) Dietary Fiber and Cell Wall Polysaccharides from Plum (Prunus domestica, L.) Fruit, Juice and Pomace: Comparison of Composition and Functional Properties for Three Plum Varieties. Food Research International, 54, 1787-1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.10.022

- 42. Wichienchot, S., Jatupornpipat, M. and Rastall, R.A. (2010) Oligosaccharides of Pitaya (Dragon Fruit) Flesh and Their Prebiotic Properties. Food Chemistry, 120, 850-857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.026

- 43. Blanch, M., Goñi, O., Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T., Escribano, M.I. and Merodio, C. (2012) Characterisation and Functionality of Fructo-Oligosaccharides Affecting Water Status of Strawberry Fruit (Fragraria vesca, cv. Mara de Bois) during Postharvest Storage. Food Chemistry, 134, 912-919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.203

- 44. Emanuel, M.A., Benkeblia, N. and Lopez, M.G. (2013) Variation of Saccharides and Fructo-Oligosaccharides (FOS) in Carambola (Averrhoa carambola) and June Plum (Spondias dulcis) during Ripening Stages. Acta Horticulturae, 1012, 77-82. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.1012.3

- 45. Guerriero, G., Giorno, F., Folgado, R., et al. (2013) Callose and Cellulose Synthase Gene Expression Analysis from the Tight Cluster to the Full Bloom Stage and during Early Fruit Development in Malus × domestica. Journal of Plant Research, 127, 173-183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-013-0586-y

- 46. Lombardo, V.A., Osorio, S., Borsani, J., et al. (2011) Metabolic Profiling during Peach Fruit Development and Ripening Reveals the Metabolic Networks That Underpin Each Developmental Stage. Plant Physiology, 157, 1696-1710. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.111.186064

- 47. Simona, N., Boldingh, H.L., Sonia, O., et al. (2013) Metabolic Analysis of Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) Berries from Extreme Genotypes Reveals Hallmarks for Fruit Starch Metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64, 5049-5063. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ert293

- 48. 苗红霞, 金志强, 刘伟鑫, 等. 香蕉果实中抗性淀粉代谢与可溶性糖含量变化的相关性[J]. 植物生理学报, 2013(8): 743-748.

- 49. 覃海兵, 莫开菊, 汪兴平. 板栗中碳水化合物的种类和抗消化性[J]. 食品科学, 2010, 31(21): 191-194.

- 50. 陈宇, 黄志明, 叶美兰, 吴锦程. 不同枇杷品种果实发育过程中果肉细胞壁组分的研究[J]. 农学学报, 2012, 2(4): 5-10.

- 51. 赵树亮, 蒋明凤, 魏媛媛, 张丙秀, 高庆玉. 梨果实生长过程中细胞壁成分的变化分析[J]. 南方农业学报, 2013, 44(11): 1861-1865.

- 52. 齐秀东, 魏建梅, 赵伶俐. 嘎拉苹果果实质地发育软化与细胞壁降解及其基因表达的关系[J]. 现代食品科技, 2015(6): 91-96.

- 53. 王保明, 丁改秀, 王小原, 等. 枣果实裂果的组织结构及水势变化的原因[J]. 中国农业科学, 2013, 46(21): 4558-4568.

- 54. 阚娟, 刘涛, 金昌海, 谢海艳. 硬溶质型桃果实成熟过程中细胞壁多糖降解特性及其相关酶研究[J]. 食品科学, 2011, 32(4): 268-274.

- 55. Missang, C.E., Maingonnat, J.F., Renard, C. and Audergon, J. (2012) Apricot Cell Wall Composition: Relation with the Intra-Fruit Texture Heterogeneity and Impact of Cooking. Food Chemistry, 133, 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.12.059

NOTES

*通讯作者。