Advances in Clinical Medicine

Vol.

13

No.

11

(

2023

), Article ID:

75173

,

8

pages

10.12677/ACM.2023.13112473

减重手术对术后早期血清尿酸水平的影响

李兆鹏,宋彦呈,李兆,郭栋,陈栋,渠佳宁,李宇*

青岛大学附属医院胃肠外科,山东 青岛

收稿日期:2023年10月11日;录用日期:2023年11月6日;发布日期:2023年11月13日

摘要

背景:研究肥胖患者在肥胖手术后早期血清尿酸(SUA)浓度的变化,并明确导致术后早期SUA浓度改变的影响因素。方法:共计纳入50例患者。在基线和每个随访点收集术前和术后观测指标。符合正态分布的测量数据用平均 ± 标准差表示,采用配对t检验计算随访点与基线之间的配对差异。非正态分布以中位数(四分位数间距)表示,两组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。采用单因素线性回归分析,探讨影响SUA变化幅度的独立因素。结果:术后1个月SUA水平显著升高(P < 0.05),其升高与患者基线尿素氮水平呈正相关(r = 0.280, P < 0.05)。ALT、AST在1个月时显著上升(P < 0.05)。Cr、BUN、HDL、LDL、总胆固醇、甘油三酯、血糖、白细胞、中性粒细胞、CRP在术后1个月显著下降(P < 0.05)。单因素回归分析显示,血尿素氮(β = 0.28, P < 0.05)为术后SUA浓度改变的危险因素。结论:减重手术患者的SUA水平在术后第一个月内升高,然后在随访期间逐渐下降。减重患者术后1个月肌酐、尿素氮水平下降,相关性研究分析提示术后1个月SUA浓度的变化与基线BUN水平相关。BUN是术后1个月SUA变化的影响因素之一。

关键词

腹腔镜袖状胃切除术,高尿酸血症,肥胖,血清尿酸

Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Early Postoperative Serum Uric Acid Levels

Zhaopeng Li, Yancheng Song, Zhao Li, Dong Guo, Dong Chen, Jianing Qu, Yu Li*

Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

Received: Oct. 11th, 2023; accepted: Nov. 6th, 2023; published: Nov. 13th, 2023

ABSTRACT

Objectives: To research the alterations in early postoperative SUA concentrations in individuals with obesity and determine the risk factors for alterations during the early postoperative period. Methods: Fifty patients were enrolled. Pre- and post-operative variables were collected at baseline and at each follow-up point. Measurements meeting a normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and paired differences between follow-up points and baseline were calculated using a paired t-test. Non-normal distribution is presented as median (interquartile spacing) and Wilcoxon rank sum test. Univariate linear regression analyses were performed to explore independent factors that influenced the magnitudes of SUA change. Results: SUA levels were significantly increased 1 month after baseline (P < 0.05), which was positively correlated with patient baseline BUN (r = 0.280, P < 0.05). ALT and AST increased significantly at 1 month (P < 0.05). Cr, BUN, HDL, LDL, total cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose, leukocytes, neutrophils, and CRP decreased significantly at 1 month after surgery (P < 0.05). Univariate regression analysis showed that blood urea nitrogen (β = 0.28, P < 0.05) was a risk factor for the postoperative SUA concentration change. Conclusions: A significant increase in SUA levels within 1 month after surgery. SUA levels increased in reduced surgery patients within the first postoperative month and then gradually decreased during the follow-up period. Patients with obesity had decreased creatinine and BUN levels 1 month after surgery, and the analysis of correlation studies suggested that the change in SUA concentration 1 month after surgery was correlated with baseline BUN levels. BUN is one of the factors affecting the SUA change at 1 month after surgery.

Keywords:Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy, Hyperuricaemia, Obesity, Serum Uric Acid

Copyright © 2023 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 背景

血清尿酸(SUA)是嘌呤代谢的最终产物 [1] ,主要来自于细胞内蛋白质分解代谢产生的核酸和其他嘌呤化合物 [2] 。研究表明,高尿酸血症不仅是痛风的生化基础 [3] ,而且在代谢综合征 [4] 、高血压 [5] 等各种疾病的发展中发挥着重要作用 [6] 。流行病学研究表明,SUA浓度与身体质量指数(BMI)密切相关 [7] 。减重手术是治疗病态肥胖最有效的方法之一 [8] 。腹腔镜袖状胃切除术(LSG)是最常用的减重术式之一,其具有手术方式简单、不破坏消化系统连续性的优点 [9] 。研究表明减重手术可以有效地降低痛风发作的发生率和SUA浓度 [10] 。因此,本文以中国肥胖手术人群为研究对象,研究短期内腹腔镜袖状胃切除术后肥胖患者SUA浓度的变化及其影响因素。

2. 资料与方法

2.1. 研究对象

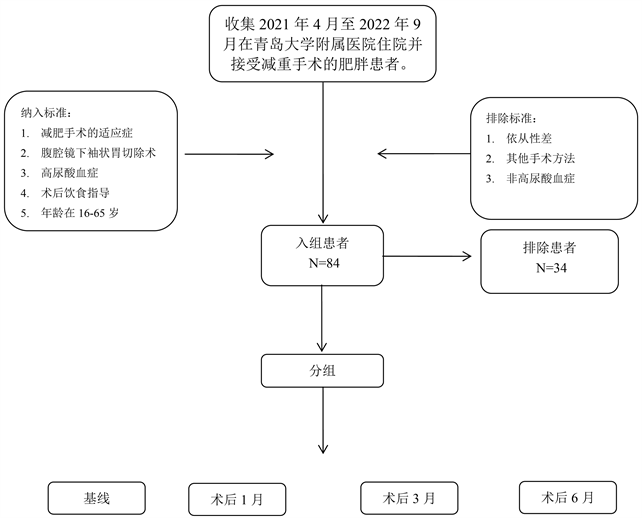

收集自2021年4月至2022年9月在青岛大学附属医院接受减重手术的肥胖患者。纳入标准:① 符合减重手术适应症;② 腹腔镜袖状胃手术;③ 高尿酸血症;④ 遵循术后饮食指导;⑤ 年龄在16~65岁。排除标准:① 依从性差;② 其他手术方法;③ 非高尿酸血症。所有患者均由同一治疗组的医生进行手术和管理。我们的研究共纳入了84例患者。根据纳入标准和排除标准,最终有50例患者参与了我们的研究。34例患者因未能完成随访而被排除(如图1)。

Figure 1. Flow diagram of this study

图1. 研究的流程图

2.2. 围术期患者管理

所有患者都遵循标准化的评估和教育方案,包括对术前患者饮食指导、及术后住院期间常规护理的细节。所有的减重手术都是由同一位外科医生完成的。患者离院后给予患者进行统一的术后饮食指导。无痛风发作的无症状高尿酸血症患者术后不给予药物降尿酸治疗。对于术前已接受降尿酸治疗的患者,在围手术期继续进行药物治疗。我们建议所有患者在术后1个月、3个月和6个月进行随访。

2.3. 观测指标

随访记录以下人口统计和临床资料,包括年龄、性别、BMI、谷丙转氨酶(ALT)、谷草转氨酶(AST)、肌酐(Cr)、高密度脂蛋白(HDL)、低密度脂蛋白(LDL)、甘油三酯、中性粒细胞、白细胞、体重减轻百分比(%WL)、空腹血糖、糖化血红蛋白(HbA1c)、胰岛素抵抗指数(HOMA-IR)、C反应蛋白(CRP)、血尿素氮(BUN)、血清尿酸(SUA)。患者于术后1个月,术后3个月,术后6个月,进行随访。主要研究终点是1个月血清尿酸浓度的变化。

2.4. 统计分析

采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计学分析。符合正态分布的测量数据用平均值 ± 标准差表示,采用配对t检验计算随访点与基线之间的差异。非正态分布以中位数(四分位数间距)表示,两组间比较采用Wilcoxon秩和检验。采用pearson相关分析探讨与SUA浓度变化有关的因素。应用单因素相关分析来明确SUA浓度变化可能的影响因素。P < 0.05被认为有统计学意义。

3. 研究结果

3.1. 研究对象基线临床特征

本研究共对2021年4月至2022年9月接受LSG治疗的50例肥胖患者进行了回顾。所有患者的人口统计学数据见表1。1个月术后随访病例共计50例,3个月病例共计12例,6个月随访病例共计19例。

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery

表1. 人口统计学特征

3.2. 主要研究节点观测指标变化

在表2中我们总结了减重术后常见观察指标变化。在术后的每个随访点,体重、BMI和%WL的下降均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。与基线水平相比,Cr水平在1个月时显著下降,在6个月时显著上升(P < 0.05)。ALT、AST在1个月时显著上升,在6个月时显著下降(P < 0.05)。BUN、HDL、LDL、总胆固醇、甘油三酯、血糖、白细胞、中性粒细胞、CRP在术后1个月显著下降(P < 0.05)。

Table 2. Changes in demographic parameters from baseline to 6-month follow-up

表2. 从基线到6个月随访的人口统计学参数的变化

数据为平均值 ± 标准差或中位数(四分位数间距)或n (%);a配对样本t检验;*P < 0.05;b基线与术后1个月;c基线与术后3个月;d基线与术后6个月。

3.3. 血清尿酸浓度变化

在术后第一天,SUA水平从423.53 ± 106.23 μmol/L迅速下降至325.83 ± 106.87 μmol/L,在1个月时上升至517.78 ± 188.16 μmol/L,然后在3个月时下降至379.83 ± 94.77 μmol/L,在6个月时下降至342.00 ± 88.95 μmol/L。与基线水平相比,术后1天的SUA水平显著下降,1个月后显著升高,然后在3个月和6个月的随访中显著下降(表3;P < 0.05)。

Table 3. The concentrations of serum uric acid at 1 day, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after bariatric surgery

表3. 减肥手术后1天、1个月、3个月、6个月的血清尿酸浓度

a配对样本t检验;*P < 0.05;b基线与术后1个月;c基线与术后3个月;d基线与术后6个月;e基线与术后1天。

3.4. 术后1月SUA水平变化与其他参数的比较

术后1个月随访时,BUN (r = 0.280, P < 0.05)与SUA水平呈正相关(表4)。减重患者BMI (r = 0.163, P > 0.05)、ΔBMI (r = 0.0.167, P > 0.05)、肌酐(r = 0.066, P > 0.05)、%WL (r = 0.012, P > 0.05)均与术后1个月SUA水平无关。在单因素回归分析中,BUN (β = 0.28, P < 0.05)为1个月后减重手术后SUA浓度改变的危险因素(表5)。患者基线白细胞(β = −0.099, P < 0.05)、中性粒细胞(β = −0.050, P < 0.05)、CRP (β = −0.089, P < 0.05)等炎症指标不是SUA水平改变的危险因素。患者基线LDL (β = −0.059, P < 0.05)、HDL (β = −0.086, P < 0.05)、总胆固醇(β = −0.015, P < 0.05)、甘油三酯(β = 0.076, P < 0.05)、血糖(β = 0.230, P < 0.05)、C肽(β = −0.015, P < 0.05)、胰岛素(β = 0.001, P < 0.05)、糖化血红蛋白(β = 0.164, P < 0.05)、HOMA-IR (β = 0.069, P < 0.05)等基线特征均不是术后1个月SUA水平改变的危险因素。

Table 4. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to determine the correlation between the magnitudes of SUA change (ΔSUA) at 1-month post-surgery and other variables

表4. 采用Pearson相关分析来确定术后1个月SUA变化的幅度(ΔSUA)与其他变量之间的相关性

*P < 0.05.

Table 5. Univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to assess independent factors influencing the ΔSUA at 1-month postoperative

表5. 采用单因素线性回归分析来评估影响术后1个月ΔSUA的影响因素

*P < 0.05;ΔSUA = SUA1月 − SUA基线。

4. 讨论

随着肥胖的发病率逐年上升,作为治疗顽固性肥胖及其并发症的有效治疗手段之一的减重手术受到了广泛关注。高尿酸血症的定义为一种SUA浓度高于一定限度的状态,即女性SUA浓度超过360 mmol/L,男性SUA浓度超过420 mmol/L [11] 。研究表明肥胖是高尿酸血症的危险因素之一 [12] [13] 。越来越多的研究人员关注减重手术对于术后SUA浓度的影响。

研究表明,随着时间的推移,减重手术可以降低高尿酸血症和痛风的发生率 [14] 。但是一部分研究人员发现减重手术后短期内SUA浓度明显波动,甚至导致痛风的发生 [15] 。因此本研究主要针对术后1月内患者SUA浓度变化进行研究。本研究发现了减重手术后高尿酸血症患者的SUA水平的显著波动。SUA浓度在减重手术一个月显著升高,随后在三个月、六个月逐渐下降。

BUN和Cr是临床上评估肾功能的常用指标之一。既往研究发现,肾功能正常的患者术后12个月SUA水平显著下降,而基线肾功能障碍的患者SUA水平下降不显著 [16] 。此外研究表明,SUA主要由肾脏排泄,肾脏SUA排泄的减少是高尿酸血症的主要原因之一 [17] 。SUA与BUN之间的关系反映了SUA与肾功能关系。与之前的研究结果一致,本研究证实了基线BUN水平与术后1个月SUA水平变化呈正相关。这提示了减重患者术后SUA浓度变化与患者肾功能密切相关。

在一项Meta分析中提到减重手术可以显著改善肾功能 [18] 。有研究报告称减重手术后,SUA水平随着肾功能的改善而降低 [19] 。为了分析SUA水平与患者肾功能的关系,本研究通过单因素分析寻找术后1个月SUA浓度变化的危险因素。本研究中,单因素分析提示了基线BUN水平是术后一个月SUA变化的影响因素。患者术后一个月的随访中Cr、尿素氮水平也显著下降(P < 0.05)。很遗憾本研究并没有发现Cr与术后1个月SUA水平变化有关。结合本研究分析结果,我们推测减重手术后高尿酸血症的改善可能与患者肾功能改善有关。

研究人员还发现,痛风的发生率与高尿酸血症、低级别全身炎症和血清Cr水平有关 [20] 。我们对术后一个月患者炎症指标、肌酐进行了分析。结果表明白细胞、中性粒细胞、CRP和Cr水平显著下降(P < 0.05)。这可能解释了有关研究提到的减重术后痛风发作率的下降 [2] 。为后续进一步围绕减重术后痛风的发作机制的研究提供了理论支持。

本研究也有几个局限性。首先,我们的研究是单中心回顾性研究,研究对象较单一。其次,患者失访的比例较高,导致术后样本量有限。因此,需要进一步的前瞻性和多中心数据收集,以更好地监测和控制肥胖手术患者术后早期的血清尿酸水平变化。

5. 结论

我们的研究表明,减重手术患者的SUA水平在术后第一个月内升高,然后在随访期间逐渐下降。减重患者术后1个月肌酐、尿素氮水平下降,相关性研究分析提示术后1个月SUA浓度的变化与基线BUN水平相关。BUN是术后1个月SUA变化的影响因素之一。我们的发现强调了对接受减重手术的患者进行个性化监测和管理计划的必要性。

声明

伦理批准:在涉及人类参与者的研究中进行的所有程序都符合机构和/或国家研究委员会的伦理标准,以及1964年赫尔辛基宣言及其后来的修正案或类似的伦理标准。

知情同意:被纳入研究的所有个体参与者均获得了知情同意。

利益冲突:所有的作者都声明他们没有利益冲突。

文章引用

李兆鹏,宋彦呈,李 兆,郭 栋,陈 栋,渠佳宁,李 宇. 减重手术对术后早期血清尿酸水平的影响

Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Early Postoperative Serum Uric Acid Levels[J]. 临床医学进展, 2023, 13(11): 17639-17646. https://doi.org/10.12677/ACM.2023.13112473

参考文献

- 1. Qiu, L., Cheng, X.Q., Wu, J., et al. (2013) Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and Its Related Risk Factors in Healthy Adults from Northern and Northeastern Chinese Provinces. BMC Public Health, 13, Article No. 664. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-664

- 2. Lu, J., Bai, Z., Chen, Y., et al. (2021) Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Serum Uric Acid in People with Obesity with or without Hyperuricaemia and Gout: A Retrospective Analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 60, 3628-3634. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keaa822

- 3. Danve, A., Sehra, S.T. and Neogi, T. (2021) Role of Diet in Hyperuricemia and Gout. Best Practice & Research: Clinical Rheumatology, 35, Article ID: 101723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2021.101723

- 4. Yanai, H., Adachi, H., Hakoshima, M., et al. (2021) Molecular Biological and Clinical Understanding of the Pathophysiology and Treatments of Hyperuricemia and Its Association with Metabolic Syndrome, Cardiovascular Diseases and Chronic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22, 9221. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179221

- 5. Borghi, C., Agnoletti, D., Cicero, A.F.G., et al. (2022) Uric Acid and Hypertension: A Review of Evidence and Future Perspectives for the Management of Cardiovascular Risk. Hypertension, 79, 1927-1936. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.17956

- 6. Yao, J., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., et al. (2022) Corre-lation of Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Blood Pressure with Uric Acid: Data from the NHANES 2017-2018. BMC En-docrine Disorders, 22, Article No. 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01112-5

- 7. Wang, H., Wang, L., Xie, R., et al. (2014) Association of Serum Uric Acid with Body Mass Index: A Cross-Sectional Study from Jiangsu Province, China. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 43, 1503-1509.

- 8. Qu, X., Zheng, L., Zu, B., et al. (2022) Prevalence and Clinical Predictors of Hyperurice-mia in Chinese Bariatric Surgery Patients. Obesity Surgery, 32, 1508-1515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05852-6

- 9. Gentileschi, P. (2012) Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy as a Primary Operation for Morbid Obesity: Experience with 200 Patients. Gastroenterology Research and Practice, 2012, Article ID: 801325. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/801325

- 10. Schiavo, L., Favrè, G., Pilone, V., et al. (2018) Low-Purine Diet Is More Effective than Normal-Purine Diet in Reducing the Risk of Gouty Attacks after Sleeve Gas-trectomy in Patients Suffering of Gout Before Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Obesity Surgery, 28, 1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2984-z

- 11. Taylor, E.N. and Curhan, G.C. (2006) Body Size and 24-Hour Urine Composition. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 48, 905-915. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.004

- 12. Larsson, S.C., Burgess, S. and Michaëlsson, K. (2018) Genetic Association between Adiposity and Gout: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Rheumatology (Oxford), 57, 2145-2148. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key229

- 13. Dehlin, M., Jacobsson, L. and Roddy, E. (2020) Global Epide-miology of Gout: Prevalence, Incidence, Treatment Patterns and Risk Factors. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 16, 380-390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0441-1

- 14. Maglio, C., Peltonen, M., Neovius, M., et al. (2017) Ef-fects of Bariatric Surgery on Gout Incidence in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study: A Non-Randomised, Prospective, Controlled Intervention Trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 76, 688-693. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209958

- 15. Xu, C., Wen, J., Yang, H., et al. (2021) Factors Influenc-ing Early Serum Uric Acid Fluctuation after Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Hyperuricemia. Obesity Surgery, 31, 4356-4362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05579-4

- 16. Roncal-Jimenez, C., García-Trabanino, R., Barregard, L., et al. (2016) Heat Stress Nephropathy from Exercise-Induced Uric Acid Crystalluria: A Perspective on Mesoamerican Nephropathy. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 67, 20-30. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.021

- 17. Nehus, E.J., Khoury, J.C., Inge, T.H., et al. (2017) Kidney Out-comes Three Years after Bariatric Surgery in Severely Obese Adolescents. Kidney International, 91, 451-458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.031

- 18. Huang, H., Lu, J., Dai, X., et al. (2021) Improvement of Renal Function after Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity Surgery, 31, 4470-4484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-021-05630-4

- 19. Hung, K.C., Ho, C.N., Chen, I.W., et al. (2020) Impact of Serum Uric Acid on Renal Function after Bariatric Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 16, 288-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2019.10.029

- 20. Romero-Talamás, H., Daigle, C.R., Aminian, A., et al. (2014) The Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Gout: A Comparative Study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 10, 1161-1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.02.025

NOTES

*通讯作者。