World Journal of Cancer Research

Vol.07 No.02(2017), Article ID:20155,7

pages

10.12677/WJCR.2017.72004

Analysis of Tumor Prosthesis Arthroplasty Complications

Junqi Huang, Wenzhi Bi*

Department of Orthopaedics, The General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army, Beijing

Received: Mar. 23rd, 2017; accepted: Apr. 6th, 2017; published: Apr. 10th, 2017

ABSTRACT

Tumor prosthesis applies to reconstruction after invasive or malignant neoplasm’s resection. Multidiscipline treatment is known to local and system control. The desirable limb-saving condition leads to more patients undergoing arthroplasty. The use of tumor prosthesis is accessible because of high survival rate. The complications of arthroplasty attach growing attention in the long- term follow-up. There are two types of failure in the retrospective study, tumor-related and non- tumor-related complications. This study is aimed to classify complications and summarize diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords:Arthroplasty, Bone Neoplasms, Complication, Revision

肿瘤假体置换术后相关并发症分析

黄俊琪,毕文志*

中国人民解放军总医院骨科,北京

收稿日期:2017年3月23日;录用日期:2017年4月6日;发布日期:2017年4月10日

摘 要

肿瘤假体置换术是侵袭性或恶性肿瘤切除术后主要的重建方式。综合治疗对骨肿瘤良好控制的前提下,肿瘤假体置换保留了患者肢体和部分功能,提高其生活质量。随着假体使用的广泛,长期随访中其并发症报道逐渐增多。通过对文献回顾性研究,将并发症主要分为两种类型,即肿瘤相关和非肿瘤相关并发症。本研究旨在对并发症进行分析研究。

关键词 :关节置换,骨肿瘤,并发症,翻修术

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

随着影像学和化疗的发展,骨肉瘤早期通过全身化疗和局部手术获得了令人满意的疗效 [1] 。新辅助化疗使肿瘤体积缩小,减轻周围水肿带,为保肢手术创造了解剖条件 [2] 。保肢手术中,以肿瘤假体置换最为常见。因为假体材料易于获得,重建早期即可进行功能锻炼 [3] 。但伴随患者生存期的延长,所报道各种重建后出现的并发症也逐渐增多 [4] [5] 。针对骨肉瘤保肢重建的普遍性和特异性情况,将其并发症分为肿瘤性和非肿瘤性。

2. 肿瘤性并发症

骨肉瘤恶性程度高,即使治疗效果令人满意,也不能完全排除复发和转移的风险。所报道的局部复发率从10%到20%不等 [6] [7] 。

治疗结束后定期复查对于早期肿瘤复发和转移的发现十分重要。及时的补救治疗可能对远期生存起到一定的积极作用 [8] 。但具体需要随访检查的时间却没有统一的标准 [9] 。随访过程中局部和全身的影像学检查必不可少,包括X线片、CT、ECT、PET-CT等。对于新发的高代谢成骨病变,应高度怀疑复发或转移的可能,需进一步检查确诊。

类似于初发骨肉瘤的治疗原则,复发和转移的患者也是以全身和局部肿瘤的控制为主,但具体化疗方案、手术方式有所改变 [10] 。通过增加化疗药物的剂量、替换化疗药物系统性控制全身肿瘤,以期能获得更佳的远期疗效 [11] [12] 。尤其是阿霉素的使用,在初次治疗过程中,已接近推荐的最大累积剂量。骨肉瘤复发和转移后,需要表柔比星或其他二线药物的替代 [13] [14] [15] 。局部肿瘤的控制是在化疗的基础上,再行局部手术切除,部分患者在术前辅助放疗 [16] 。在复发的肿瘤患者中,未累及血管神经的患者仍具备保肢的条件。但多数患者因肿瘤范围广泛不得不行根治性截肢手术。

虽然通过定期检查能早期发现复发肿瘤,改进化疗方案、根治性切除和辅助放疗等积极治疗肿瘤病灶,但远期生存并不理想,报道的生存率约为20% [9] [17] 。研究发现增加化疗剂量所带来疗效的收益并不显著,二线药物的替代在复发肿瘤患者中表现敏感的情况也较少 [18] 。

3. 非肿瘤性并发症

针对肿瘤假体置换手术,非肿瘤性并发症基于假体工艺的欠缺和技术的不完善 [19] 。化疗对肿瘤良好的控制使长期生存的患者逐年增多,假体的高频率使用和长期磨损增加了其失败的发生率 [20] 。非肿瘤性并发症对患者功能、生活质量影响较大。对于一些术后出现假体严重感染等危及患者生命的情况下还需行截肢处理。非肿瘤性并发症可分为无菌性松动、感染、结构性失败、软组织性失败。

1. 无菌性松动

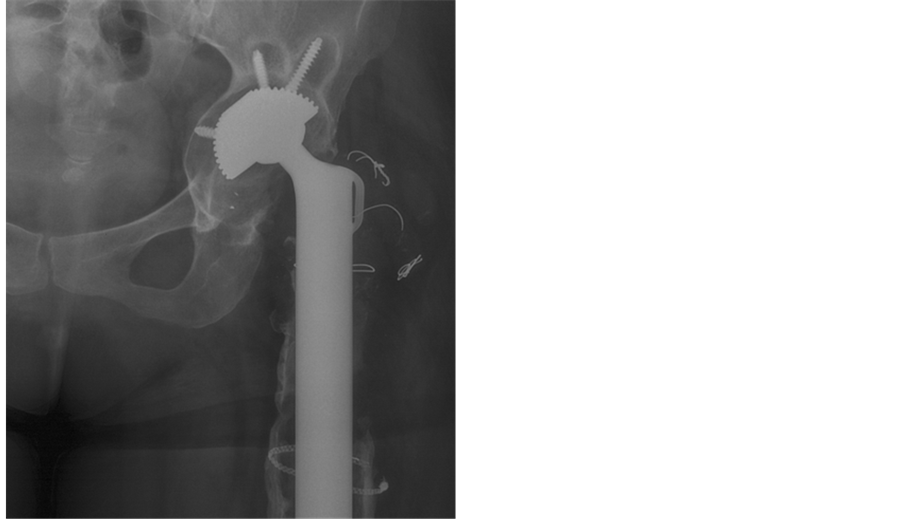

无菌性松动主要是由于长期机械压力、接触面相对运动和局部宿主对材料反应造成 [21] 。长期受到机械压力,材料表面发生相对运动,产生磨屑,刺激破骨细胞、间充质细胞发生骨溶解 [22] 。另一方面,应力遮挡造成周围骨质疏松,降低假体固定强度。无菌性松动可表现为关节的不稳、活动受限、影像学上位置的改变、透光影的出现(图1)。低毒性感染也可有类似表现,在诊断时应与之鉴别 [23] 。

假体松动可尝试石膏或支具临时固定,使组织周围形成纤维瘢痕,以牺牲关节活动为代价增加肢体的稳定性。一般情况下,置入材料松动的患者因肢体不稳而活动受限,长期缺乏锻炼造成肌肉萎缩。因此,一期翻修重新建立稳定的骨和关节支撑是恢复患者功能最直接有效的方法 [24] 。

2. 感染

感染是肿瘤假体失败的主要并发症。随访报道其发生率在2%~20% [25] [26] 。手术时间的延长,失血量的增多,伤口愈合不良等都会增加假体感染的风险。有文献报道患者BMI值与感染也有一定相关性 [27] 。症状体征、化验炎性指标、菌群培养是判断感染的依据。临床上主要以感染的预防为主,对手术时间较长、出血较多的患者应预防性使用抗生素 [28] 。有观点认为多种抗生素联合应用并不能获得比单种抗生素更好的预防感染的效果,长期使用抗生素易致耐药菌的产生 [29] 。

恶性肿瘤患者的治疗常涉及放化疗。化疗药物抑制患者骨髓,导致白细胞降低,免疫功能受到影响;局部放疗不利于伤口愈合,使患者在治疗期间易发生感染。因此不同于普通假体置换,肿瘤患者整个治疗期间都应监测感染指标,对于有感染征象的患者及时使用敏感抗生素。

急性感染患者敏感抗生素应用和关节清理,成功率能达到75%。一期假体翻修重点在于清创。彻底清除术野炎性肉芽,更换聚乙烯材料,灭菌溶液的浸泡决定清创的成败 [30] 。二期翻修术是假体感染治疗的金标准 [31] 。占位器的置入一方面局部持续释放抗生素控制感染,另一方面维持软组织张力,为二期手术提供软组织基础。待炎性指标控制后行二期假体置入术以恢复肢体功能。

Figure 1. Patient underwent tumor resection and arthroplasty 2 years ago. The feel of unsteady joint and the restrictive of activity were explicit. The graph showed density reduction around prosthesis

图1. 患者左股骨近端肿瘤扩大切除、特质人工假体置换术后2年,出现关节不稳、活动受限。X线片示假体周围密度减低

3. 结构性失败

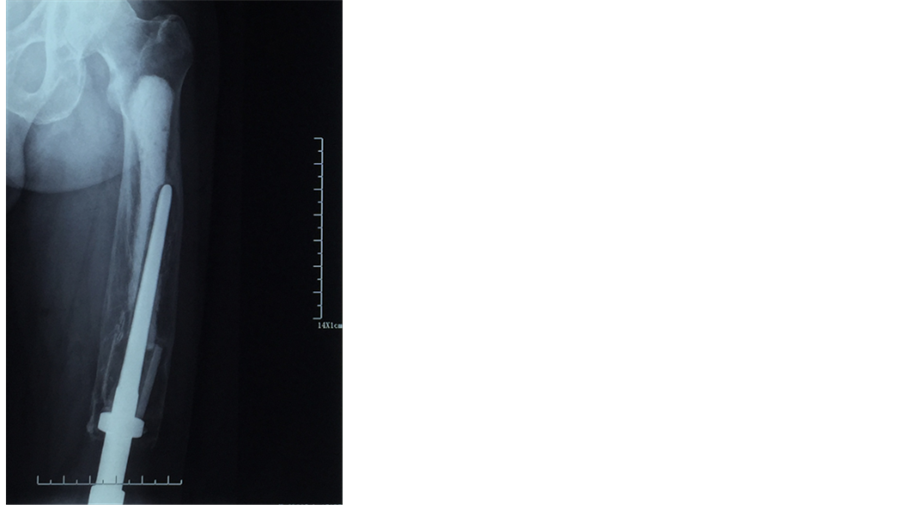

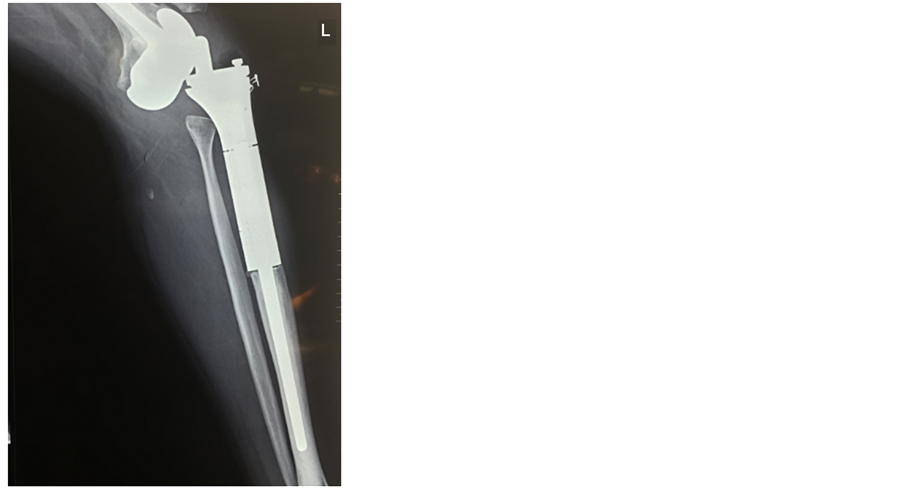

假体断裂、脱位、假体周围骨折都属于支撑结构重建失败的因素(图2、图3)。为获得满意肿瘤边界,切除的骨组织较多,同时增加了假体的应力支撑。应力遮挡导致假体周围骨质疏松,假体承受较多的重力,使假体断裂及周围骨折的风险升高。结构性的失败后应及时固定或更换假体,避免二次损伤周围血管、神经、软组织。

Figure 2. Periprosthetic fracture

图2. 假体周围骨折

Figure 3. Prosthesis dislocation

图3. 假体脱位

骨连续性的破坏可采用钢板螺钉固定的方法 [31] 。钉道需绕开髓腔内假体柄的位置。研究显示双皮质螺钉表现出更好的稳定性 [33] 。术中操作难免会造成骨膜的破坏,存在骨延迟愈合或骨不愈的情况 [34] 。随着锁定技术的使用使骨折的处理相对容易 [35] 。假体的断裂则需重新置入新的假体替换。骨缺损部位可通过取自体骨、植异种骨、填充人工材料的方法重建。

4. 软组织性失败

软组织性因素包括韧带、肌腱的断裂、松弛。软组织对术后功能和关节的动态稳定影响较大。如肩袖组织、臀中肌、伸膝装置等是关节活动和稳定的软组织基础。在肿瘤累及范围广泛时,为避免肿瘤切除不完整,易过多切除软组织。在重建过程中软组织张力过高或已有潜在的撕裂,术后活动导致韧带、肌腱的断裂,影响功能 [36] 。

针对不同解剖部位,应采用不同措施预防。上肢肌肉、韧带切除较多时可采用适当短缩肢体、人工韧带延长的方法。髋关节处应保证肿瘤广泛切除的基础上尽量保留大转子,便于臀中肌重建。髌韧带是膝关节屈伸重要结构,胫骨重建伸膝装置术后出现伸膝迟滞、髌韧带断裂的病例并不少见 [37] 。应尽量保留胫骨结节骨瓣便于髌韧带重建;对于胫骨结节无法保留,髌韧带长度不足的患者可转位腓肠肌内侧头 [38] 。

一旦发生软组织问题,单独考虑稳定因素时,可应用石膏、支具塑形,利用纤维瘢痕达到固定的效果。而有功能需求的患者,则需二次手术重建损伤的软组织。

4. 小结

无论是肿瘤性并发症还是非肿瘤性并发症,对患者及其家庭身心、经济等都是一种挑战。肿瘤的控制是患者长期生存的保障。有效的化疗和完整的广泛切除,降低肿瘤转移率、复发率,是肿瘤治疗中最基本的原则。而对假体重建认识的不断进步、假体设计的不断完善、手术技巧的提升是重建肢体功能的保障。在降低假体并发症,延长假体使用寿命方面,充当着重要的角色。

基金项目

国家自然科学基金(编号81472513)。

文章引用

黄俊琪,毕文志. 肿瘤假体置换术后相关并发症分析

Analysis of Tumor Prosthesis Arthroplasty Complications[J]. 世界肿瘤研究, 2017, 07(02): 21-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.12677/WJCR.2017.72004

参考文献 (References)

- 1. Anderson, M.E. (2016) Update on Survival in Osteosarcoma. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 47, 283-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.022

- 2. Ferrari, S. and Serra, M. (2015) An Update on Chemotherapy for Osteosarcoma. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 16, 2727-2736. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2015.1102226

- 3. Lopresti, M., Rancati, J., Farina, E., et al. (2015) Rehabilitation Pathway after Knee Arthroplasty with Mega Prosthesis in Osteosarcoma. Recenti Progressi in Medicina, 106, 385-392.

- 4. Li, D., Ma, H., Zhang, W., et al. (2015) Analysis of Implant-Related Complications after Hinge Knee Replacement for Tumors around the Knee. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi, 29, 936-940.

- 5. Houdek, M.T., Wagner, E.R., Wilke, B.K., et al. (2016) Long Term Outcomes of Cemented Endoprosthetic Reconstruction for Periarticular Tumors of the Distal Femur. Knee, 23, 167-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2015.08.010

- 6. Bacci, G., Forni, C., Longhi, A., et al. (2007) Local Recurrence and Local Control of Non-Metastatic Osteosarcoma of the Extremities: A 27-Year Experience in a Single Institution. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 96, 118-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.20628

- 7. Palmerini, E., Jones, R.L., Marchesi, E., et al. (2016) Gemcitabine and Docetaxel in Relapsed and Unresectable High-Grade Osteosarcoma and Spindle Cell Sarcoma of Bone. BMC Cancer, 16, 280. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2312-3

- 8. The ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group (2014) Bone Sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 25, iii113-iii123. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu256

- 9. Rothermundt, C., Seddon, B.M., Dileo, P., et al. (2016) Follow-up Practices for High-Grade Extremity Osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer, 16, 301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2333-y

- 10. Kang, X., Huang, Z., Shi, A., et al. (2016) Deficiencies in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Metastatic Osteosarcoma: A Chinese Multidisciplinary Survey. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi, 19, 153-160.

- 11. Puri, A., Gulia, A., Hawaldar, R., et al. (2014) Does Intensity of Surveillance Affect Survival after Surgery for Sarcomas? Results of a Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 472, 1568-1575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3385-9

- 12. Chou, A.J., Gupta, R., Bell, M.D., et al. (2013) Inhaled Lipid Cisplatin (ILC) in the Treatment of Patients with Relapsed/Progressive Osteosarcoma Metastatic to the Lung. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 60, 580-586. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24438

- 13. Yu, L., Cai, L., Hu, H., et al. (2014) Experiments and Synthesis of Bone-Targeting Epirubicin with the Water-Soluble Macromolecular Drug Delivery Systems of Oxidized-Dextran. Journal of Drug Targeting, 22, 343-351. https://doi.org/10.3109/1061186X.2013.877467

- 14. Gosiengfiao, Y., Reichek, J., Woodman, J., et al. (2012) Gemcitabine with or without Docetaxel and Resection for Recurrent Osteosarcoma: The Experience at Children’s Memorial Hospital. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 34, e63-e65.

- 15. Machak, G.N., Polotskiĭ, B.E., Meluzova, O.M., et al. (2010) Treatment of Relapsed Osteosarcoma. Role of Chemotherapy Using Ifosamide and Carboplatin. Voprosy Onkologii, 56, 220-225.

- 16. Dinçbaş, F.O., Koca, S., Mandel, N.M., et al. (2005) The Role of Preoperative Radiotherapy in nonmetAstatic High-Grade Osteosarcoma of the Extremities for Limb-Sparing Surgery. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, 62, 820-828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.006

- 17. Fagioli, F., Aglietta, M., Tienghi, A., Ferrari, S., et al. (2002) High-Dose Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Relapsed Osteosarcoma: An Italian Sarcoma Group Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 2150-2156. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.08.081

- 18. Kushnir, I., Kolander, Y., Bickels, J., et al. (2014) Is It Important to Maintain High-Dose Intensity Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Adults with Osteosarcoma. Medical Oncology, 31, 936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0936-1

- 19. Wirganowicz, P.Z., Eckardt, J.J., Dorey, F.J., et al. (1999) Etiology and Results of Tumor Endoprosthesis Revision Surgery in 64 Patients. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 358, 64-74.

- 20. Hardes, J., Ahrens, H., Gosheger, G., et al. (2014) Management of Complications in Megaprostheses. Der Unfallchirurg, 117, 607-613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-013-2477-z

- 21. Pajarinen, J., Lin, T.H., Nabeshima, A., et al. (2016) Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Aseptic Loosening of Total Joint Replacements. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 105, 1195-1207.

- 22. Maloney, W.J. and Smith, R.L. (1996) Periprosthetic Osteolysis in Total Hip Arthroplasty: The Role of Particulate Wear Debris. Instructional Course Lectures, 45, 171-182.

- 23. Kempthorne, J.T., Ailabouni, R., Raniga, S., Hammer, D. and Hooper, G. (2015) Occult Infection in Aseptic Joint Loosening and the Diagnostic Role of Implant Sonication. BioMed Research International, 2015, Article ID: 946215. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/946215

- 24. Aibinder, W.R., Schoch, B., Schleck, C., et al. (2017) Revisions for Aseptic Glenoid Component Loosening after Anatomic Shoulder Arthroplasty. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 26, 443-449.

- 25. Jeys, L.M., Kulkarni, A., Grimer, R.J., et al. (2008) Endoprosthetic Reconstruction for the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Tumors of the Appendicular Skeleton and Pelvis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-America Volume, 90, 1265-1271. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.F.01324

- 26. Myers, G.J., Abudu, A.T., Carter, S.R., et al. (2007) Endoprosthetic Replacement of the Distal Femur for Bone Tumours: Long-Term Results. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume, 89, 521-526. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.89B4.18631

- 27. Dowsey, M.M. and Choong, P.F. (2008) Obesity Is a Major Risk Factor for Prosthetic Infection after Primary Hip Arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 466, 153-158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-007-0016-3

- 28. Morii, T., Yabe, H., Morioka, H., et al. (2010) Postoperative Deep Infection in Tumor Endoprosthesis Reconstruction around the Knee. Journal of Orthopaedic Science, 15, 331-339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00776-010-1467-z

- 29. McDonald, M., Grabsch, E., Marshall, C., et al. (1998) A Single- versus Multiple-Dose Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Major Surgery: A Systematic Review. ANZ Journal of Surgery, 68, 388-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04785.x

- 30. Peel, T., May, D., Buising, K., et al. (2014) Infective Complications Following Tumour Endoprosthesis Surgery for Bone and Soft Tissue Tumours. European Journal of Surgical Oncology, 40, 1087-1094.

- 31. Juul, R., Fabrin, J., Poulsen, K., et al. (2016) Use of a New Knee Prosthesis as an Articulating Spacer in Two-Stage Revision of Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty. Knee Surgery & Related Research, 28, 239-244. https://doi.org/10.5792/ksrr.2016.28.3.239

- 32. Ehlinger, M., Adam, P., Di Marco, A., et al. (2011) Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures Treated by Locked Plating: Feasibility Assessment of the Mini-Invasive Surgical Option. A Prospective Series of 36 Fractures. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 97, 622-628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2011.01.017

- 33. Giesinger, K., Ebneter, L., Day, R.E., et al. (2014) Can Plate Osteosynthesis of Periprosthethic Femoral Fractures Cause Cement Mantle Failure around a Stable Hip Stem? A Biomechanical Analysis. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 29, 1308-1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.12.015

- 34. Rorabeck, C.H. and Taylor, J.W. (1999) Periprosthetic Fractures of the Femur Complicating Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 30, 265-277.

- 35. Jentzsch, T., Erschbamer, M., Seeli, F., et al. (2013) Extensor Function after Medial Gastrocnemius Flap Reconstruction of the Proximal Tibia. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 471, 2333-2339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-2851-8

- 36. Althausen, P.L., Lee, M.A., Finkemeier, C.G., et al. (2003) Operative Stabilization of Supracondylar Femur Fractures above Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Comparison of Four Treatment Methods. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 18, 834-839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00339-5

- 37. Gosheger, G., Gebert, C., Ahrens, H., et al. (2006) Endoprosthetic Reconstruction in 250 Patients with Sarcoma. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 450, 164-171.

- 38. Dobbs, R.E., Hanssen, A.D., Lewallen, D.G. and Pagnano, M.W. (2005) Quadriceps Tendon Rupture after Total Knee Arthroplasty. Prevalence, Complications, and Outcomes. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-America Volume, 87, 37-45.

NOTES

*通讯作者。