Botanical Research

Vol.3 No.05(2014), Article ID:14045,8 pages

DOI:10.12677/BR.2014.35023

New Advances in Legume Systematics

1State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

Email: *happyking@ibcas.ac.cn

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: Jul. 12th, 2014; revised: Aug. 10th, 2014; accepted: Aug. 17th, 2014

ABSTRACT

New advances in legume systematics are reviewed herein. The Leguminosae, being the third largest angiosperm family with about 751 living genera and ca. 19,500 species, has a global distribution as well as a key ecological and economic importance. The Leguminosae might have made their debut since the Late Cretaceous, boasting an abundant and diverse fossil and extant taxa in the Cenozoic. Recent molecular systematic studies suggested that the traditional classification system of legumes subdivided into three subfamilies (i.e., Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoideae, and Papilionoideae) has not been evolutionarily reasonable. Instead, the currently proposed systems of classification for legumes with more than three subfamilies are better supported despite the uncertainty for the concrete number and delimitation of subfamilies. In addition, proper phylogenetic relationships among the four families (i.e., Leguminosae, Polygalaceae, Quillajaceae, and Surianaceae) in the order Fabales have hitherto been poorly resolved, and the basal nodes of phylogenetic tree topologies in Leguminosae are not well supported. How to reclassify the paraphyletic subfamily Caesalpinioideae and its own pivotal taxa (e.g., Cercideae, Cassieae, Detarieae, and Caesalpinieae) desperately need more detailed researches.

Keywords:Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoideae, Papilionoideae, Systematics, Multi-Subfamilial Classification System

豆科植物系统学研究新进展

林彦翔1,2,王 祺1*,申 思1

1中国科学院植物研究所,系统与进化植物学国家重点实验室,北京

2中国科学院大学,北京

Email: *happyking@ibcas.ac.cn

收稿日期:2014年7月12日;修回日期:2014年8月10日;录用日期:2014年8月17日

摘 要

本文综述了近年来豆科植物系统学研究的新进展。豆科Leguminosae作为被子植物第三大科,约有751个现生属和19,500种,全球广泛分布,具有重要的生态和经济价值。豆科植物可能起源于白垩纪晚期,其化石和现生分类群在新生代变得丰富多样。近来的分子系统学研究表明,传统的豆科3亚科(即云实亚科Caesalpinioideae、含羞草亚科Mimosoideae和蝶形花亚科Papilionoideae)分类系统从进化上解读并不合理,而最新提出的豆科多亚科分类系统则获得较好的支持,尽管亚科的具体数目和划分仍然存在很大争议。此外,豆目中最为密切的豆科、远志科Polygalaceae、皂皮树科Quillajaceae和海人树科Surianaceae的准确系统发育关系仍然悬而未决,而且豆科系统发育树图基部节点的支持率也不高,并系的云实亚科及其内部的一些关键分类群(例如紫荆族Cercideae、决明族Cassieae、甘豆族Detarieae和云实族Caesalpinieae)的重新划分亟需详细研究。

关键词

豆科,云实亚科,含羞草亚科,蝶形花亚科,系统学,多亚科分类系统

1. 引言

豆科Leguminosae是生命之树共生固氮(symbiotic nitrogen fixation)支系中最大、最成功的1个植物类群[1] [2] ,它在被子植物中仅次于兰科Orchidaceae和菊科Asteraceae,共计约有751个现生属、19,500种[3] [4] 。豆科植物全球广布,为温带、半干旱区–季节性干旱区、热带雨林和稀树草原生态系统中重要的区系组成成分[5] ,它们生活史丰富多样,既有乔木和木质藤本类型,也有灌木、草质藤本和草本类型[6] 。豆科植物可能起源于白垩纪晚期,它们在新生代的化石记录丰富多样,主要包括木材、叶、小叶、荚果、种子、花序、花和花粉等[7] ,最早可信的大化石(荚果)发现于哥伦比亚上古新统地层(距今约58百万年前)[8] ,但有关豆科的生物地理起源问题尚有争议[5] [6] 。近来的分子钟数据显示豆科干部类群的起源时间约为60~70百万年前,而传统上划分的云实亚科Caesalpinioideae、含羞草亚科Mimosoideae和蝶形花亚科Papilionoideae的冠部类群的起源时间相差不大,约为39~59百万年前,表明豆科3个亚科在古近纪很短的时间内就快速分异了[9] 。此外,豆科在过去的6000万年里比其它一般的被子植物分化速率要高,它拥有被子植物中最大的属——黄芪属Astragalus(约2900种)和一些进化最快的分支[6] [9] [10] 。

豆科植物是被人类利用和驯化最为广泛的类群之一,包括一些全球性的粮食和蔬菜作物[6] ,例如大豆Glycine max、菜豆属Phaseolus、蚕豆Vicia faba、花生Arachis hypogaea、小扁豆Lens culinaris、鹰嘴豆Cicer arietinum和豌豆Pisum sativum等,以及重要的温带和热带草料作物,例如苜蓿Medicago sativa、车轴草属Trifolium和银合欢Leucaena leucocephala等。豆科植物的共生固氮作用为农业和自然界生态系统提供了重要的生物氮素来源,促进了农作物可持性生产和陆地生态系统的服务功能[1] [2] ,例如朱缨花属Calliandra、南洋樱属Gliricidia、印加木属Inga和银合欢属Leucaena是热带农林的基本组成,有利于森林恢复和土壤改良。此外,还有许多豆科植物具有观赏和药用价值,例如槐属Sophora、凤凰木属Delonix、刺桐属Erythrina、羽扇豆属Lupinus、合欢属Albizia、金合欢属Acacia、紫荆属Cercis、皂荚属Gleditsia、肥皂荚属Gymnocladus、紫藤属Wisteria、葛属Pueraria和甘草属Glycyrrhiza等。本文综述了豆科植物系统学中传统和最新分类观点、系统发育研究中存在的突出问题以及研究展望。

2. 豆科3亚科分类系统

豆科根据一些显著的、容易识别的形态性状(如叶枕、荚果以及花的特征)就可以界定,在豆目中是1个较短的系统发育分支。有些植物分类学家把豆类植物划分为3个独立的科,即含羞草科Mimosaceae、云实科Caesalpiniaceae和蝶形花科Papilionaceae [11] [12] ,但这种观点未被广泛接受[6] [13] 。传统上主要依据形态性状把豆科分为3个亚科,即云实亚科Caesalpinioideae、含羞草亚科Mimosoideae和蝶形花亚科Papilionoideae [6] [14] [15] 。过去,豆科3亚科分类系统为人们普遍接受,而且容易教学。尽管存在一些例外类群,但植物志、野外植物学手册和其它经典文献中为了方便大多采用3个亚科编排,许多标本馆馆藏标本亦是如此,这意味着豆科的亚科等级尤为重要。

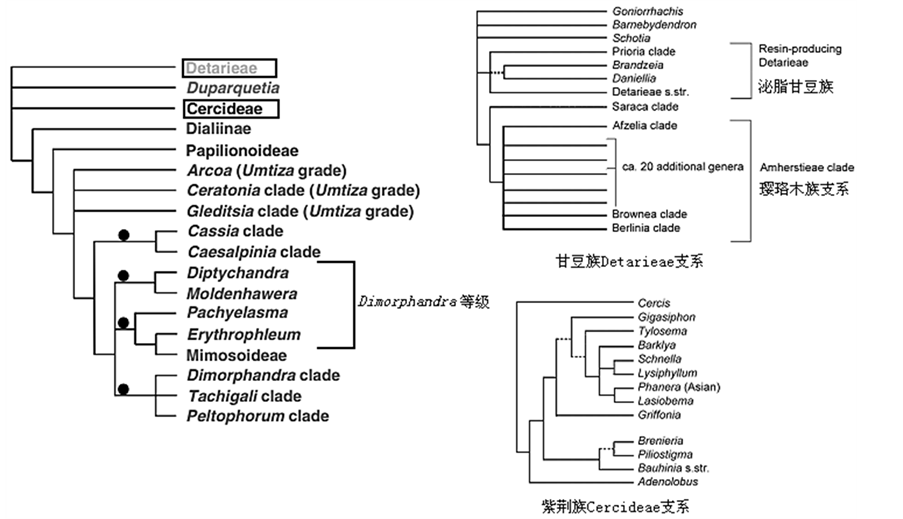

近来的分子系统学研究表明,将豆科分为3个亚科的方案从进化上解读并不合理。因为3个亚科——云实亚科、含羞草亚科和蝶形花亚科不能如实反映豆科的系统发育关系,含羞草亚科和蝶形花亚科被嵌入到并系的云实亚科中[6] [14] -[19] (图1)。2001年,在澳大利亚堪培拉举行的第4届国际豆科植物会议上,人们深知传统的豆科分类系统已经过时,但由于当时缺乏强有力的系统发育分析方法和证据支持,只能暂时搁置提出新的分类系统。近年来,由于豆科诸多属的分子序列数据的增加和系统发育分析方法的改进,其系统学研究有了很大进展。然而,要想建立1个新的豆科分类系统,即便是过渡类型,也会面临巨大的挑战[3] [4] 。

3. 豆科多亚科分类系统

1981年,系列著作《豆科系统学进展》(Advances in Legume Systematics)的出版标志着现代豆科系统学研究的兴起[20] 。2005年,Lewis等在《世界的豆类》(Legumes of the World)中综述了Advances in Legume

Figure 1. A simplified phylogenetic tree of Leguminosae (colors represent different subfamilies and black dots indicate the nodes with a low support) (after[4] )

图1. 简化的豆科系统发育树(颜色代表不同的亚科,黑点表示这些节点的支持率低) (据[4] )

Systematics首卷出版近25年以来的豆科系统发育研究成果,阐述了豆科植物分类处理上发生变化的缘由[6] 。2010年,豆科系统发育工作组[Legume Phylogeny Working Group(LPWG)]成立,该国际团体致力于推动豆科系统发育研究,其主要任务是提出豆科系统发育研究概要和计划安排以及拟要解决的核心问题。

2013年,第6届国际豆科植物会议在南非约翰内斯堡召开,其主题为“豆科新分类系统”,于是豆科分类系统的重新修订被正式提上议事日程[3] 。关于豆科分类系统,亚科的数目最为大多数植物学家所关心,而族的数目的少许变化并没有引起太多异议。关于亚科的数目,许多植物分类学家强调其实用性和普及性,例如植物志、野外指南以及植物学教学。人们难以接受豆科15个亚科的新分类系统,而倾向于继续使用传统的3亚科分类系统。因为用单系类群定义每一个亚科非常困难,所以人们希望保留含羞草亚科,并且避免增加一些小的亚科。最合理的解决方案可能是承认1个或多个、更大、更具包容性的亚科,但这种方案也不容乐观,因为亚科越大,从形态特征上就更加难以界定,特别是广义的云实亚科。

目前主要提出了3个豆科多亚科分类方案。1) 豆科15个亚科的分类系统,它将含羞草亚科和蝶形花亚科嵌入云实亚科(图2(a))。这种分类方案主要有2处导致亚科数目增多:a)“Umtiza等级”,它包括3个独立平行的谱系。这个等级包括决明族Cassieae、甘豆族Detarieae和云实族Caesalpinieae中的7个属,过去基于形态学和分子数据把它们归为1个“Umtiza支系”[21] ,但最新的分子系统发育分析表明它并非单系[15] [22] 。人们大都赞成用单系类群来命名亚科或族。因此,“Umtiza等级”的3个非单系类群作为1个亚科来命名是不可行的;b) 含羞草亚科Mimosoideae加上Pachyelasma 和Erythrophleum(有时也包括Diptychandra和Moldenhawera[22] )。如果保留传统的含羞草亚科,那么增加的亚科可能就需要纳入其它谱系。然而,这个节点的支持率较低,在近来的系统发育分析中也不稳定[15] [22] [23] 。同时,它们种的取样相关性总是很低,几乎很少有形态性状支持这种系统发育关系。扩大含羞草亚科的定义是1个解决方案,这样将使其包括Dimorphandra等级中的一些属,但这会造成含羞草类植物原来的组成发生改变。这是因为Dimorphandra支系中的其它一些属包含在Tachigali支系和Peltophorum支系,而与Diptychandra,Moldenhawera,Pachyelasma和Erythrophleum所在的Dimorphandra等级相比,它们与含羞草类植物更为相似。因此,适当扩大含羞草亚科的界定标准可能面临质疑。此外,Dimorphandra支系本身并非单系,在充分取样后它各成员之间的关系以及和其它属的关系也可能发生改变;2) 豆科10~12个亚科的分类系统(图2(b)),它保留了含羞草亚科,但在某些节点处的系统发育关系不稳定,所以亚科的

Figure 2. Three schemes for the multi-subfamilial classification systems of legumes (colors represent different subfamilies containing various taxon components) (after [4] )

图2. 豆科多亚科分类系统的3个方案(颜色代表不同亚科的分类群组成) (据[4] )

数目将增加,例如Arcoa 和Peltophorum所在分支被认为是1个独立的亚科,但它的支持率太低,接受它还为时尚早;3) 豆科6个亚科的分类系统(图2(c)),它将合并云实族Caesalpinieae分支和决明属Cassia支系中所有的类群,与含羞草亚科构成1个较大的亚科。然而,这种分类方案相比于传统的含羞草亚科将会产生1个形态愈加多样化的亚科,虽然不会比传统的云实亚科更复杂,但是通过形态特征也很难界定。因为它把所有具二回羽状复叶的豆科植物都并在一起,其实其中一些谱系仅具有一回羽状复叶或二回羽状复叶来源的叶状柄[24] 。

总体上,人们期望豆科亚科的数目划分得尽可能少。在第6届国际豆科植物会议上,大约有一半的专家赞成豆科6亚科分类系统(图2(c))。其余专家大多倾向于建立5到6个亚科,广义的云实亚科-含羞草亚科分支暂不作分类处理,留待将来再作详细研究。

4. 豆科的基部类群

豆科的分类问题主要集中在其基部类群的划分上,即并系类群——云实亚科的细分和归并,尤其是基部几个关键节点——紫荆族Cercideae、甘豆族Detarieae和Umtiza等级的分类处理以及其中的大属的细分和归并问题,例如紫荆族Cercideae中羊蹄甲属Bauhinia的分类最值得关注。豆科谱系基部类群节点的支持率都不高。目前,云实亚科的171个属、2250种可划分为4个族,即紫荆族Cercideae、甘豆族Detarieae、决明族Cassieae和云实族Caesalpinieae[6] 。然而,分子证据仅支持紫荆族和甘豆族是单系类群,其中紫荆族是豆科其余类群的姐妹群[15] [18] [25] 。

4.1. 紫荆族Cercideae支系

分子、形态和化石证据都支持紫荆族作为单系[15] [26] -[28] (图3)。该族最显著的形态特征是叶为单叶、2裂叶或2小叶,而且具有明显的叶枕结构[26] -[28] 。紫荆族中属的关系比较复杂,最新的分析认为紫荆属Cercis是族内其它分类群的姐妹群,而泛热带属——羊蹄甲属Bauhinia最为人们所关注,大约有150~300

Figure 3. A phylogenetic tree of the basal, paraphyletic group Caesalpinioideae in Leguminosae (after [3] )

图3. 豆科基部的并系类群——云实亚科的系统发育树(据[3] )

种,通常被划为1个大属[27] 。根据花粉形态和分子系统学研究,广义的羊蹄甲属Bauhinia sensu lato并不是单系类群,其中的Barklya、Gigasiphon、Lasiobema、Lysiphyllum、Phanera和Tylosema与狭义羊蹄甲属Bauhinia sensu stricto有所不同[28] 。近来提出,美洲分布的Phanera种最好归为1个独立的属Schnella而与亚洲分布的Phanera分开[23] [28] [29] (图3)。

4.2. 甘豆族Detarieae支系

近来的系统发育分析都支持Mackinder[30] 划分的甘豆族Detarieae为单系。广义的甘豆族Detarieae s. l.包括2大分支,a) 其一是单系类群“泌脂甘豆族”(resin-producing Detarieae),它包括Prioria支系和狭义的甘豆族Detarieae s. s.”这2个小的分支(图3),它们在形态上有很大变异,但大多数种能产生二环二萜类化合物[31] [32] ;b) 其二是“璎珞木族Amherstieae支系”,它是“泌脂甘豆族”的姐妹群,由“Saraca”支系和“Afzelia”支系(主要为亚洲种)、“Brownea”支系(主要为新世界种)和“Berlinia”分支(主要为非洲种)构成[33] [34] 。璎珞木族Amherstieae其余的属形成1个庞大的多分支(图3)。此外,南非的Schotia与南美的Goniorrhachis和Barnebydendron的分类位置还不确定,但它们是“泌脂甘豆族”和璎珞木族支系的姐妹群(图3)。

4.3. Umtiza支系

这个支系由3个独立平行的谱系构成,包括决明族Cassieae、甘豆族Detarieae和云实族Caesalpinieae中的7个属,其细分和归并关系到豆科分类系统亚科数目的变化。Umtiza支系具有一些共同的性状,例如花小、绿色,绝大多数为雌雄异株,这在云实亚科中实属罕见。因此,过去基于形态和分子证据将其归为1个支系,但近来研究表明它们并非单系,划分为Arcoa、长角豆属Ceratonia支系和皂荚属Gleditsia支系[15] [22] (图3)。

4.4. Dialiinae支系

这个支系包括了亚族Dialiina、Labicheinaee(决明族Cassieae)和Poeppigia,是蝶形花亚科Papilionoideae、含羞草亚科Mimosoideae、大多数云实族Caesalpinieae以及决明族Cassieae谱系所形成的1个庞大分支的姐妹群[15] (图3)。Dialiinae支系中许多种具特殊的花序类型(如简单花序、复聚伞花序或二歧聚伞花序)、花部缺失,产生核果或翅果,这些性状明显不同于其它豆科植物[18] [35] 。Dialiinae支系中属的关系中,除了少数几个,其它都没有很好地解决,属下关系更是知之甚少。

4.5. 决明属Cassia支系和云实属Caesalpinia支系

Manzanilla和Bruneau[22] 利用质体和核DNA取样分析认为,云实属Caesalpinia支系和决明属Cassia支系的姐妹群关系的支持率较低,但这2个支系归并在一起是云实族Caesalpinieae分支的其余类群加上含羞草亚科Mimosoideae这一大分支的姊妹群(图3)。

4.6. Peltophorum、Tachigali和Dimorphandra支系

这些支系的关系目前还未很好解决(图3)。根据形态和分子证据,Haston等[36] 认为“Peltophorum”支系和南美的“Tachigali”支系是2个支持很高的单系,但Dimorphandra支系实际上是并系类群,其中Burkea、Dimorphandra、Mora、Stachyothyrsus和Dinizia(可能Campsiandra)形成了1个低支持率的支系[15] ,而Dimorphandra等级的其它4个属(图3),即Diptychandra、Moldenhawera、Pachyelasma和Erythrophleum是含羞草亚科基部的1个并系类群,它们是Peltophorum、Tachigali和Dimorphandra 3个支系并成一大分支的姐妹群。

5. 豆科系统学研究展望

本文综述了近年来豆科系统学研究的新进展。最值得关注的是,过去的豆科3亚科分类系统(即云实亚科Caesalpinioideae、含羞草亚科Mimosoideae和蝶形花亚科Papilionoideae)已经过渡到当前的豆科多亚科分类系统[3] [4] 。然而,新提出的豆科多亚科分类系统尚不成熟,亚科数目的多少取决于对其中一些分支的划分,尤其是豆科基部的并系类群—云实亚科的细分和归并,但这些问题迄今都未圆满解决。此外,豆目中关系最为密切的4个科—豆科Leguminosae、远志科Polygalaceae、皂皮树科Quillajaceae和海人树科Surianaceae的准确系统发育关系至今尚有争议[25] [37] [38] 。有关豆科的生物地理起源问题也没有达成一致意见,近来提出特提斯海道附近的热带地区最有可能关系着豆科植物的起源和早期分化[5] [6] [26] ,但这个特提斯海道假说(Tethys Seaway hypothesis)还需要更有力的系统发育关系和化石证据支持。因此,豆科系统学未来的研究方向是瞄准更高水平的分类,随着豆科的分子系统学、形态学、发育生物学和古植物学等研究的不断深入,其分类系统也在不断地完善。将来,人们心目中的豆科分类系统不仅要如实反映系统发育关系,也要注重其实用性。

致 谢

作者衷心感谢中国科学院植物研究所李振宇研究员、南京地质古生物研究所史恭乐博士、英国皇家植物园Brian Schrire博士和美国蒙大拿州立大学Mattew Lavin博士提供部分重要文献,并讨论豆科植物化石和生物地理起源问题。本工作受国家自然科学基金项目(批准号41372029,40972015)和现代古生物学和地层学国家重点实验室(中国科学院南京地质古生物研究所)项目(批准号123106)联合资助,特此感谢!

参考文献 (References)

- [1] Sprent, J.I. (2007) Evolving ideas of legume evolution and diversity: A taxonomic perspective on the occurrence of nodulation. New Phytologist, 174, 11-25.

- [2] Sprent, J.I. (2008) 60Ma of legume nodulation. What’s new? What’s changing? Journal of Experimental Botany, 59, 1081-1084.

- [3] LPWG (The Legume Phylogeny Working Group) (2013) Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: Progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades. Taxon, 62, 217-248.

- [4] LPWG (The Legume Phylogeny Working Group) (2013) Towards a new classification system for legumes: Progress report from the 6th International Legume Conference. South African Journal of Botany, 89, 3-9.

- [5] Schrire, B.D., Lavin, M. and Lewis, G.P. (2005) Global distribution patterns of the Leguminosae: Insights from recent phylogenies. Biologiske Skrifter, 55, 375-422.

- [6] Lewis, G., Schrire, B., Mackinder, B. and Lock, M. (2005) Legumes of the World. Royal Botanic Gardens, Richmond.

- [7] Herendeen, P.S. and Dilcher, D.L. (1992) Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 4, the Fossil Record. Royal Botanic Gardens, Richmond.

- [8] Wing, S.L., Herrera, F., Jaramillo, C.A., Gómez-Navarro, C., Wilf, P. and Labandeira, C.C. (2009) Late Paleocene fossils from the Cerrejón Formation, Colombia, are the earliest record of neotropical rainforest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 106, 18627-18632.

- [9] Lavin, M., Herendeen, P.S. and Wojciechowski, M.F. (2005) Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the Tertiary. Systematic Biology, 54, 575-594.

- [10] Scherson, R.A., Vidal, R. and Sanderson, M.J. (2008) Phylogeny, biogeography, and rates of diversification of the New World Astraglaus (Leguminosae) with an emphasis on South American radiations. American Journal of Botany, 95, 1030-1039.

- [11] Steyermark, J.A., Berry, P.E., Yatskievych, K. and Holst, B.K. (2001) Flora of the Venezuelan Guayana. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis.

- [12] Cullen, J., Knees, S.G. and Cubey, H.S. (2011) The European Garden Flora. 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- [13] Lewis, G.P. and Schrire, B.D. (2003) Leguminosae or Fabaceae? In: Klitgaard, B. and Bruneau, A., Eds., Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 10, Higher Level Systematics, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 1-3.

- [14] Wojciechowski, M.F., Lavin, M. and Sanderson, M.J. (2004) A phylogeny of the legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matk gene sequences resolves many well-supported subclades within the family. American Journal of Botany, 91, 1846-1862.

- [15] Bruneau, A., Mercure, M., Lewis, G.P. and Herendeen, P.S. (2008) Phylogenetic patterns and diversification in the caesalpinioid legumes. Botany, 86, 697-718.

- [16] Doyle, J.J., Doyle, J.L., Ballenger, J.A., Dickson, E.E., Kajita, T. and Ohashi, H. (1997) A phylogeny of the chloroplast gene rbcl in the Leguminosae: Taxonomic correlations and insights into the evolution of nodulation. American Journal of Botany, 84, 541-554.

- [17] Kajita, T., Ohashi, H., Tateishi, Y., Bailey, C.D. and Doyle, J.J. (2001) rbcL and legume phylogeny, with particular reference to Phaseoleae, Millettieae, and allies. Systematic Biology, 26, 515-536.

- [18] Herendeen, P.S., Bruneau, A. and Lewis, G.P. (2003) Phylogenetic relationships in the caesalpinioid legumes: A preliminary analysis based on morphological and molecular data. In: Bruneau, A. and Klitgaard, B.B., Eds., Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 10, Higher Level Systematics, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 37-62.

- [19] Wojciechowski, M.F. (2003) Reconstructing the phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae): An early 21st century perspective. In: Bruneau, A. and Klitgaard, B.B., Eds., Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 10, Higher Level Systematics, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 5-35.

- [20] Polhill, R.M. and Raven, P.H. (1981) Advances in Legume Systematics. Part 1, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond.

- [21] Herendeen, P.S., Lewis, G.P. and Bruneau, A. (2003) Floral morphology in caesalpinioid legumes: Testing the monophyly of the “Umtiza Clade”. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 164, S393-S407.

- [22] Manzanilla, V. and Bruneau, A. (2012) Phylogeny reconstruction in the Caesalpinieae grade (Leguminosae) based on duplicated copies of the sucrose synthase gene and plastid markers. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 65, 149- 162.

- [23] Sinou, C., Forest, F., Lewis, G.P. and Bruneau, A. (2009) The genus Bauhinia s. l. (Leguminosae): A phylogeny based on the plastid trnL-trnF region. Botany, 87, 947-960.

- [24] Champagne, C.E.M., Goliber, T.E., Wojciechowski, M.F., Mei, R.W., Townsley, B.T., Wang, K., Paz, M.M., Geeta, R. and Sinha, N.R. (2007) Compound leaf development and evolution in the legumes. Plant Cell, 19, 3369-3378.

- [25] Bello, M.A., Bruneau, A., Forest, F. and Hawkins, J.A. (2009) Elusive relationships within order Fabales: Phylogenetic analyses using matK and rbcL sequence data. Systematic Biology, 34, 102-114.

- [26] Wang, Q., Song, Z.Q., Chen, Y.F., Shen, S. and Li, Z.Y. (2014) Leaves and fruits of Bauhinia (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae, Cercideae) from the Oligocene Ningming Formation of Guangxi, South China and their biogeographic implications. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 14, 1-16.

- [27] Wunderlin, R., Larsen, K. and Larsen, S.S. (1981) Cercideae. In: Polhill, R.M. and Raven, P.H., Eds., Advances in Legume Systematics, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 107-116.

- [28] Lewis, G.P. and Forest, F. (2005) Cercideae. In: Lewis, G., Schrire, B.D., Mackinder, B. and Lock, M., Eds., Legumes of the World, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 57-67.

- [29] Wunderlin, R.P. (2010) New combinations in Schnella (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae: Cercideae). Phytoneuron, 49, 1- 5.

- [30] Mackinder, B. (2005) Tribe Detarieae. In: Lewis, G., Schrire, B.D., Mackinder, B. and Lock, M., Eds., Legumes of the World, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 68-109.

- [31] Langenheim, J.H. (2003) Plant resins: Chemistry, evolution, ecology, and ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland.

- [32] Fougère-Danezan, M., Maumont, S. and Bruneau, A. (2007) Relationships among resin producing Detarieae s.l. (Leguminosae) as inferred by molecular data. Systematic Biology, 32, 748-761.

- [33] Wieringa, J.J. and Gervais, G.Y.F. (2003) Phylogenetic analyses of combined morphological and molecular data sets on the Aphanocalyx-Bikinia-Tetraberlinia group (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae, Detarieae s.l.). In: Klitgaard, B.B. and Bruneau, A., Eds., Advances in Legume Systematics, Part 10, Higher Level Systematics, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, 181-196.

- [34] Mackinder, B.A. and Pennington, R.T. (2011) Monograph of Berlinia (Leguminosae). Systematic Botany Monographs, 91, 1-117.

- [35] Zimmerman, E., Prenner, G. and Bruneau, A. (2013) Floral morphology of Apuleia leiocarpa (Caesalpinioideae: Cassieae), an unusual andromonoecious legume. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 174, 154-160.

- [36] Haston, E.M., Lewis, G.P. and Hawkins, J.A. (2005) A phylogenetic reappraisal of the Peltophorum Group (Caesalpinieae: Leguminosae) based on the chloroplast trnL-F, rbcL and rpS16 sequence data. American Journal of Botany, 92, 1359-1371.

- [37] Bello, M.A., Hawkins, J.A. and Rudall, P.J. (2010) Floral ontogeny in Polygalaceae and its bearing on the homologies of keeled flowers in Fabales. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 171, 482-498.

NOTES

*通讯作者。