Advances in Clinical Medicine

Vol.

14

No.

02

(

2024

), Article ID:

81073

,

14

pages

10.12677/ACM.2024.142470

伴右向左分流的偏头痛患者左房前后径 与脑白质病变的相关研究

张健1,江毅2,单体茹3,赵洪芹4*

1青岛大学临床医学院,山东 青岛

2青岛市城阳区人民医院神经内二科,山东 青岛

3青岛市城阳区人民医院老年医学科,山东 青岛

4青岛大学医学院附属医院神经内科,山东 青岛

收稿日期:2024年1月21日;录用日期:2024年2月14日;发布日期:2024年2月22日

摘要

目的:脑白质病变(White Matter Hyperintensities, WMHs)在偏头痛中很常见,可能与右向左分流(Right- to-Left-shunt, RLS)有关。近年来,有研究表明RLS对左心房扩大(left atrium enlargement, LAE)有影响。然而,关于LAE与伴有RLS偏头痛患者的WMHs发病机制相关性的研究甚少。我们旨在探讨LAE对伴RLS偏头痛患者的WMHs的影响,并进一步评估偏头痛患者WMHs的独立危险因素。方法:本研究选入自2016年1月至2021年8月在青岛大学附属医院神经内科病房住院及门诊就诊的偏头痛患者共计206名。选入研究对象均符合《国际头痛疾病分类》(第3版)的诊断标准(International Classification of Headache Disorders (3rd edition beta version))。所有入选的受试者均接受了经颅多普勒造影(C-TCD)、经胸超声心动图(TEE)、MRI检查。入选标准:(1) 年龄在18~65岁之间;(2) 声窗良好,能有效执行Valsalva手法(VM)。排除具有以下特征的患者:(1) 急性脑卒中。(2) 合并严重心肺疾病。(3) 创伤、手术和妊娠。(4) 严重肝肾功能不全、癌变、严重感染、癫痫等精神病。(5) 不能配合Valsalva动作。(6) 颅内或颅外动脉狭窄。由于合并心功能不全、Valsalva动作无法完成、严重的颅内动脉狭窄以及声窗不良而排除18人,最终纳入本研究共188人。入选的受试者均参与有关脑血管疾病的主要危险因素的标准化问卷调查,包括性别、年龄、高血压病史、糖尿病史、高脂血症病史、缺血性脑卒中病史,偏头痛既往史以及家族史、酒精状况(每月至少一次饮酒5年以上)和吸烟情况(连续或累计吸烟6个月以上,包括研究前6个月戒烟的前吸烟者)。此外,所纳入对象均完成颅脑MRI的T2加权序列(T2WI)和液体衰减反转恢复序列(Flare-image)扫描以确定WMHs。在Flare和T2WI图像上,脑白质病变被定义为侧脑室周围区域(通常是额部、后角或放射冠区、脑室旁)和深部白质的高强度病灶,可散发或融合成斑片状。通过经胸超声心动图(transthoracic echocardiography, TTE)确定左心房前后径、左心房长径、左心房短径、左室舒张末期内径、左室收缩末期内径、室间隔厚度、左室后壁厚度、肺动脉压以及心脏射血分数。所有研究对象完成对比增强经颅多普勒检查(Contrastenhanced Transcranial Doppler, c-TCD),通过c-TCD在双侧颞窗和枕窗探及到的微气泡信号证明RLS的存在。根据探测到的微栓子信号(MB)分级及划分流量大小:0级(未探测到微栓子信号)、I级(1~10 MB)、II级(11~25 MB)、III级(>25 MB,未形成雨帘)、IV级(形成雨帘);小流量(<10 MB)、中流量(10~25 MB)、大流量(>25 MB或形成雨帘)。通过颅脑MRI分为有WMHs组和无WMHs组并进行各心脏径线、年龄等相关危险因素的组间差异比较。此外,根据c-TCD分为有RLS和无RLS组以及大小不同流量亚组,比较组间各心脏径线、脑白质病变及相关危险因素有无差异。针对上述资料进行单因素分析并将具有统计学意义的变量(p < 0.05)进行多因素Logistic回归分析,讨论关于伴有RLS偏头痛患者脑白质病变的独立危险因素。所用资料的统计分析均通过软件SPSS 24.0完成。结果:本研究最终纳入188名偏头痛患者,平均年龄43.3岁(18至65岁),其中男性64例(34%)、女性124例(66%),伴有脑白质病变的偏头痛患者97例(51.6%),不伴有脑白质病变的患者91例(48.4%)。与无脑白质病变组相比,伴有脑白质病变的偏头痛患者的左心房前后径更大(LAAPD 3.59 ± 0.43 VS. 3.27 ± 0.34, p = 0.000)。此外,伴WMHs的偏头痛组的左房长径(LA major axis)、左室舒张末期内径(LVDd)、左室收缩末期内径(LVDs)均大于不伴有WMHs组(LA major axis 4.79 ± 0.57 VS. 4.50 ± 0.47, p = 0.000; LVDd 4.53 ± 0.30 VS. 4.43 ± 0.28, p = 0.012; LVDs 2.89 ± 0.30 VS. 2.80 ± 0.28, p = 0.041)。而且,伴有WMHs偏头痛患者的左心室射血分数(LVEF)小于无WMHs的偏头痛患者(63.98 ± 3.07 VS. 65.02 ± 3.52; p = 0.031)。在年龄、高血压、高脂血症以及缺血性脑血管病史方面,有无WMHs偏头痛组间样存在明显差异。此外,伴有RLS的偏头痛患者(占纳入对象的69.14%)被进一步分为大分流量亚组79名和小分流量亚组51名。与包含58名不伴RLS的偏头痛患者组比较,RLS (+)组偏头痛患者更易出现脑白质病变(%) (75 (57.5) VS. 22 (38.6), p = 0.018),而且RLS (+)组中偏头痛病史更常见(%) (104 (80) VS. 37 (63.8), p = 0.028),组间比较显示RLS与脑白质病变及偏头痛关系密切。但在大、小分流量亚组之间脑白质病变、各心脏径线均无统计学差异。Logistic回归分析显示,左心房前后径增大是偏头痛患者脑白质病变发生的独立危险因素(OR = 9.352; 95% CI = 2.081~42.027; p = 0.004)。结论:在偏头痛患者中,伴有WMHs组的LAAPD明显大于无WMHs组,此外,WMHs组的LA major axis、LVDd及LVDs也显著大于无WMHs组。而在有无RLS组间以及RLS大小分流亚组之间LAAPD无差异。研究表明,在伴RLS的偏头痛患者中LAAPD与WMHs有关,而且LAAPD增大是偏头痛患者发生WMHs的独立危险因素。

关键词

偏头痛,脑白质病变,左心房前后径,右向左分流

Association between Left Atrial Anterior-Posterior Diameter and White Matter Hyperintensities in Migraineurs with Right-to-Left-Shunt

Jian Zhang1, Yi Jiang2, Tiru Shan3, Hongqin Zhao4*

1Clinical Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao Shandong

2Department of Neurology II, Chengyang District People’s Hospital, Qingdao Shandong

3Department of Geriatrics, Chengyang District People’s Hospital, Qingdao Shandong

4Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University Medical College, Qingdao Shandong

Received: Jan. 21st, 2024; accepted: Feb. 14th, 2024; published: Feb. 22nd, 2024

ABSTRACT

Background and Purpose: White Matter Hyperintensities (WMHs) are common in migraine and might be related to right-to-left-shunt (RLS). Recently, several studies indicated the effect of RLS on left atrium enlargement (LAE). Nevertheless, there is few literature on the association between LAE and the pathogenesis of WMHs in migraineurs with RLS. We aim to explore the effect of LAE on WMHs in migraineurs with RLS, and further evaluate independent risk factor of WMHs in migraine patients. Methods: A total of 206 enrolled participants were diagnosed with migraine by International Classification of Headache Disorders, (3rd edition beta version) at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University from January 2016 to August 2021. All selected subjects underwent Contrast Enhancement Transcranial Doppler (C-TCD), Transthoracic echocardiography (TEE), MRI, Inclusion criteria was as follows: (1) age between 18 to 65 years; (2) with well acoustic window and effective execution of Valsalva maneuver (VM). Patients with following characteristic were excluded: (1) acute stroke; (2) complicated with severe cardiopulmonary disease; (3) trauma, surgery and pregnancy; (4) severe liver and renal dysfunction, cancer, serious infection, epilepsy and other psychosis; (5) ineffective execution of VM; (6) intracranial or extracranial arterial stenosis. 18 migraineurs were excluded due to cardiac insufficiency, inability to complete Valsalva movements, severe intracranial artery stenosis, and poor acoustic window, a total of 188 patients were finally included in this study. The enrolled subjects participated a standardized, structured questionnaire to obtain information of main risk factor to cerebral vascular disease, including age, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, alcohol status (alcohol intake at least once a month for more than 5 years) and cigarette smoking (continuous or cumulative smoking for 6 months or more and include former smoker who had quitted smoking up to 6 months before the study). In addition, all subjects underwent brain MRI T2-weighted sequence (T2WI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence (Flare-image) scans to determine WMHs. On Flare and T2WI images, leukodystrophy is defined as high-intensity lesions in the periventricular area (usually the frontal, posterior horn, or radio-crown area, paravulicular) and deep white matter that can be sporadic or fused into patchy patches. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was used to determine the anteroposterior diameter of the left atrium, the long diameter of the left atrium, the short diameter of the left atrium, the end diastolic diameter of the left ventricle, the end systolic diameter of the left ventricle, the thickness of the ventricular septum, the posterior wall of the left ventricle, the pulmonary artery pressure, and the ejection fraction. All enrolled migraineurs underwent Contrastenhanced Transcranial Doppler (c-TCD), and the presence of RLS was confirmed by microbubble signals detected by TCD in bilateral temporal and occipital Windows. According to detected microembolus signal (MB) classification and flow size: Level 0 (no microembolus signal detected), Level I (1~10 MB), Level II (11~25 MB), Level III (>25 MB, no rain curtain formed), Level IV (rain curtain formed); Small traffic (<10 MB), medium traffic (10~25 MB), and large traffic (>25 MB). Brain MRI was used to divide WMHs group into WMHs group and WMHS group without WMHS group. In addition, according to c-TCD, they were divided into groups with RLS and without RLS as well as different flow subgroups. The differences in cardiac diameters, leukoencephalopathy and related risk factors were compared between groups. Based on the above data, univariate analysis and multivariate Logistic regression analysis were performed for statistically significant variables (p < 0.05) to discuss the independent risk factors for WMHs in migraineurs with RLS. Statistical analysis of the data used was completed by SPSS 24.0 software. Results: A total of 188 migraine patients with a mean age of 43.3 years (18~65 years) were enrolled in this study, including 64 males (34%) and 124 females (66%), 97 migraineurs (51.6%) with WMHs and 91 patients (48.4%) without WMHs. The LAAPD of the left atrium was larger in migraineurs with WMHs compared with those without WMHs (LAAPD 3.59 ± 0.43 VS. 3.27 ± 0.34, p = 0.000). In addition, the left atrial long diameter (LA major axis), left ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter (LVDd), and left ventricular end-systolic internal diameter (LVDs) in WMHs group were greater than in non- WMHs group (LA major axis 4.79 ± 0.57 VS. 4.50 ± 0.47, p = 0.000; LVDd 4.53 ± 0.30 VS. 4.43 ± 0.28, p = 0.012; LVDs 2.89 ± 0.30 VS. 2.80 ± 0.28, p = 0.041). Moreover, the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in WMHs group was lower than that in non-WMHs group (63.98 ± 3.07 VS. 65.02 ± 3.52; p = 0.031). There were also significant differences in age, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and ischemic cerebrovascular history between the groups with and without WMHs. In addition, migraineurs with RLS (69.14% of the enrolled subjects) were further divided into the large shunt subgroup of 79 patients and the small flow subgroup of 51 patients. Comparing with 58 subjects without RLS, 130 migraineurs with RLS were more likely to suffer WMHs (%) (75 (57.5) VS. 22 (38.6), p = 0.018). Furthermore, the history of migraine was more common in the RLS positive group (%) (104 (80) VS 37 (63.8), p = 0.028), and comparison among groups showed that RLS was closely associated with WMHs and migraine. However, there was no significant difference in WMHs and cardiac diameter between large and small flow subgroups. Logistic regression analysis showed that the enlarged LAAPD of left atrium was an independent risk factor for WMHs in migraineurs (OR = 9.352; 95% CI = 2.081 42.027; p = 0.004). Conclusions: In migraine patients, LAAPD in the group with WMHs was significantly larger than that in group without WMHs. In addition, LA major axis, LVDd and LVDs in the group with WMHs were also obviously higher than those without WMHs. There was no difference in LAAPD between groups with and without RLS or between subgroups with different shunts. Our studies showed that LAAPD is associated with WMHs in migraineurs, and increased LAAPD is an independent risk factor for WMHs in migraine patients.

Keywords:Migraine, White Matter Hyperintensities (WMHs), Left Atrium Anterior-Posterior Diameter (LAAPD), Right to Left Shunt (RLS)

Copyright © 2024 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

1. 引言

偏头痛是临床中常见的神经内科疾病,是以单侧或双颞侧反复发作的搏动性疼痛为主要临床表现。有研究显示偏头痛在普通人群中的发病率约为10%~12%,且多见于年龄小于50岁的中青年女性 [1] 。发病前可伴有视觉、体觉先兆,发作时可有恶心呕吐症状,长期反复发作常引起失眠、焦虑、疲劳及记忆力减退等合并症 [2] [3] 。有多项文献表明,偏头痛与脑白质病变以及隐源性脑卒中密切相关 [4] [5] [6] ,因此偏头痛给人们的日常生活及身心健康造成了很大的困扰。然而,关于偏头痛的发病机制众说纷纭,目前较为认可的发病机制有化学物质触发机制、皮质扩散性抑制及血管源性学说 [7] [8] ,还有研究认为偏头痛与右向左分流(right to left shunt, RLS)有关 [9] 。

RLS是主肺动脉或左右心腔之间的异常通道,卵圆孔未闭(Patent Foramen Ovale, PFO)是RLS常见形式,在偏头痛患者中PFO的发病率高达64.64% [10] 。分流量的大小取决于缺损严重程度以及通道两侧的压力差。当静脉系统的压力高于动脉系统时,未经氧合的静脉血由PFO直接进入体循环。动物模型试验 [11] 也表明反常栓塞是导致偏头痛发作的主要机制之一,反常栓塞是静脉系统中微小栓子在特定情况下(如Valsalva动作)可通过右向左分流进入体循环引发微小梗死病灶,通过皮质扩散性抑制诱发偏头痛。此外关于偏头痛的化学物质触发机制假说认为来自静脉系统中的如5-羟色胺、血清素等血管活性物质,在未经肺循环灭活的情况下直接由分流处进入动脉循环系统导致偏头痛 [12] 。

RLS不仅参与偏头痛发病机制,而且Regatelli等人 [13] 发现RLS与左心房增大(left atrium enlargement, LAE)相关,此外RLS还可能参与偏头痛患者脑白质病变(white matter hyperintensities, WMHs)的发病机制 [14] [15] 。还有文献 [16] 认为以左心房增大为主要结构改变的心房性心脏病可能参与了脑卒中的发病机制。然而,也有研究报道偏头痛患者的RLS与WMHs无明显相关性 [17] 。关于WMHs存在多种学说,年龄、高血压已被证实为WMHs的独立危险因素,而且在各个年龄段中高胆固醇与WMHs的严重程度成正相关 [18] 。此外,有研究发现高同型半胱氨酸是WMHs重要危险因素 [19] 。WMHs发病机制复杂。除上述因素外,还包括脑小血管病变(Small vessel disease SVD) [20] 、细胞凋亡及遗传因素 [21] 等多种原因。然而关于LAE与偏头痛患者WMHs的相关性研究甚少。所以,该研究旨在探讨影响伴有RLS偏头痛患者WMHs的相关因素以及LAE在WMHs发病机制中的作用。

2. 材料与方法

2.1. 研究对象

本研究选入自2016年1月至2021年8月在青岛大学附属医院神经内科病房住院及门诊就诊的偏头痛患者206名。选入研究对象均符合《国际头痛疾病分类》(第3版)的诊断标准。根据研究排除标准最终纳入共计188人。本研究经过青岛大学医学院伦理委员会批准,且获得所有研究对象的知情同意。

2.1.1. 入组标准

1) 年龄18~65岁成年偏头痛患者;

2) 颞窗透声良好,检查配合度高;

3) 符合《国际头痛疾病分类》(第3版)偏头痛诊断标准;

4) 无急性心脑血管疾病及颅内外血管狭窄;

2.1.2. 排除标准

1) 年龄 < 18岁或>65岁偏头痛患者;

2) 透声窗不良、不能配合Valsalva动作及对比增强经颅多普勒检查者;

3) 缺血性脑卒中急性期及恢复期;

4) 严重的心肺肾等功能不全;

5) 肿瘤、癫痫及严重的感染;

6) 妊娠、近1个月手术、创伤者;

7) 颅内外动脉狭窄;

2.1.3. 入组设计

1) 通过c-TCD将偏头痛患者分为RLS (+)、RLS (−)组;

2) 根据c-TCD将RLS (+)组分为大分流量亚组(Large Shunt)和低分流量亚组(Mild Shunt);

3) 根据MRI (Flare and T2WI-image)偏头痛患者分为WMHs (+)、WMHs (−)组。

2.2. 研究方法

2.2.1. 脑血管疾病危险因素及相关病史调查

包括年龄、高血压、糖尿病、高脂血症、饮酒史(每月饮酒至少一次5年以上)、吸烟史(连续或累积吸烟6个月以上,包括在研究前6个月内的戒烟者),TIA/缺血性脑卒中既往史、偏头痛既往史及家族史。

2.2.2. 脑白质病变的检查方法

核磁共振3TMRI (Siemens Magnetom Prisma 3.0T, Germany)的T2加权图像(T2WI)和FLAR像。WMHs表现为放射冠区、侧脑室周围区域的皮质下(通常是额部、后角和脑带)或深部白质的散在点状或融合为斑片状高信号(图1)。

2.2.3. 左心房前后径测量方法

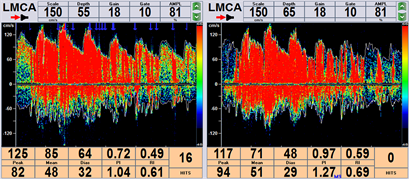

采用经胸超声心动图(transthoracic echocardiography, TTE) (EPIQ7C Philips)测量左房前后内径(LAAPD),此外,本研究还测量了其它反映左心增大的心脏结构标志数据:左房短径、左房长径、左室舒张末期内径(LVDd)、左室收缩末期内径(LVDs)、室间隔(IVS)、左室后壁厚度(LVPW);心功能指标:左室射血分数(LVEF)、肺动脉收缩压(PASP) (图2)。

Figure 1. (a) WMHs on FLAR image; (b) WMHs on T2WI image

图1. (a) WMHs FLAR像表现;(b) WMHs T2WI表现

Figure 2. (a) LAAPD; (b) LA major axis; (c) LVDd; (d) LVDs; (e) LA minor axis

图2. (a) 左心房前后内径;(b) 左房长径;(c) 左室舒张末期内径;(d) 左室收缩末期内径;(e) 左心房短径

2.2.4. RLS的测定

本研究采用经颅多普勒超声系统EMS-9A Delica,通过C-TCD (bubble test)检测RLS及其程度。指导受试者进行标准的Valsalva动作:首先让患者深吸气,然后用力呼气并屏住呼吸10~15秒。通过Valsalva动作可以增加胸内压来影响肺循环及体循环之间的血流分布及自主神经功能状态,可提高右向左分流的阳性监测率。在确定受试者良好声窗以及配合度情况下,我们首先选择检测大脑中动脉(MCA)人工微栓塞信号,如果MCA信号不良,我们可选择椎动脉(VA)监测微栓塞。将20 g静脉导管针插入患者肘中静脉。将9 ml生理盐水、1 ml空气和1滴患者血液(稳定混合物中的微泡)组成的活性生理盐水通过三通阀在两个10 ml注射器中混合均匀后注入肘中静脉。整个过程分三次进行:第一次在平静呼吸状态下进行,后两次注射分别在10s Valsalva动作开始前5秒进行。两次Valsalva动作之间需要休息至少5分钟。活性生理盐水注射后20 s内观察至少1个微泡(MB)信号诊断RLS。根据TCD监视器显示的信号计数,我们在本研究中将RLS分为小分流(<25 MB)和大分流(>25 MB或有雨帘效应)两种程度(图3)。

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 3. Contra-enhanced transcranial Doppler (c-TCD): (a) Mild shunt (1~25 MB), (b) Large shunt (curtain effect)

图3. 对比增强经颅多普勒(c-TCD):(a) 小分流量(1~25 MB),(b) 大分流量(形成雨帘)

2.2.5. 统计学方法

采用SPSS 24.0版软件进行统计学分析,对符合正态分布的数据采用t检验,计数资料用百分比表示,计量资料采用均数 ± 标准差表示,组间比较采用卡方检验或菲舍尔精确检验。logistic回归分析评价左心房前后径对偏头痛患者WMHs的影响以及WMHs独立危险因素,p值<0.05为有统计学意义。

3. 结果

本研究选入偏头痛患者共计206人,根据排查标准,因慢性心力衰竭排除4例,Valsalva动作不配合排除6例,因声窗不良排除4例,因局限性颅内动脉狭窄排除4例,最终纳入共计188例年龄在18~65岁之间的偏头痛患者。其中RLS (+) 130例(69.15%),RLS (−) 58例(30.85%),其中RLS (+)偏头痛患者中小分流亚组51例(39.23%),大分流亚组79例(60.77%)。此外188名偏头痛患者中WMHs (+)97例(51.60%),WMHs (−) 91例(48.40%)。

3.1. 伴有和不伴有RLS偏头痛患者之间的脑血管疾病危险因素、脑白质病变、心腔径线、射血分数的比较

本研究共纳入偏头痛患者188例,其中女性124例(65.96%),男性64例(34.04%)。伴有RLS偏头痛患者130例,其中女性88例(67.7%),无RLS偏头痛患者中女性36例(62.1%)。虽然偏头痛患者中女性占比高于男性,但性别在伴有和不伴有RLS的组间无差异,此外如年龄、吸烟、饮酒、高血压等脑血管危险因素以及心脏腔室径线、心脏射血分数、肺动脉压在有无RLS组间差异均无统计学意义。在所纳入的伴有RLS的受试者中有偏头痛既往病史的患者104例,而在无RLS受试者中有相关既往史的偏头痛患者37例。可以发现在伴有RLS者受试者中有偏头痛既往史的患者占比较高80%,而在不伴有RLS的偏头痛患者中既往有头痛病史者占比63.8%,两组之间存在显著的统计学差异(p < 0.05)。此外130例有RLS的受试者中75例偏头痛患者发现患有WMHs,发生率57.5%,在58例无RLS患者中患脑白质病变为22例,发生率38.6%,有关脑白质病变在伴有和不伴有RLS的偏头痛患者组之间的差异具有显著统计学意义(p < 0.05) (表1)。

Table 1. Vascular risk factors, WMHs, chamber diameters, cardiac function makers in migraineurs with RLS and without RLS

表1. 伴有和不伴有右向左分流的偏头痛患者之间的血管危险因素、WMHs、房室直径、心功能标志物的比较

aFischer精确检验;RLS:右向左分流,TIA:短暂性脑缺血发作。

3.2. 小分流量与大分流量偏头痛患者的脑血管疾病危险因素、脑白质病变、心腔径线、射血分数的组间比较

130名伴有RLS偏头痛患者分为小分流量亚组(51例)和大分流量亚组(79例)。脑血管疾病危险因素、脑白质病变、心腔径线、心脏射血分数以及肺动脉压的组间差异均无统计学意义(p > 0.05) (表2)。

Table 2. Vascular risk factors, WMHs, chamber diameters and cardiac function makers in migraineurs with different RLS degrees

表2. 不同分流量的偏头痛患者间的血管危险因素、WMHs、心脏腔室径线、心脏功能标志物的比较

aFischer精确检验。

3.3. 有WMHs组与无WMHs组的脑血管疾病危险因素、心腔径线、心脏射血分数以及肺动脉压的组间比较

所纳入的188名偏头痛患者分为有WMHs组(97例)和无WMHs组(91例),其中伴有WMHs受试者的平均年龄49.28岁,且女性占比67%。结果发现WMHs组的偏头痛患者平均年龄明显大于无WMHs组(49.28 ± 11.83 VS. 36.27 ± 10.25, p = 0.000),组间差异有统计学意义。在脑血管危险因素中,高血压、高血脂在WMHs组中比率分别为35.1%、12.4%,明显高于无WMHs组(高血压34 (35.1%) VS. 8 (8.8%),p = 0.000;高脂血症12 (12.4%) VS. 1 (1.1%);p = 0.003),高血压、高脂血症的组间差异存在统计学意义(p < 0.05)。此外,研究显示与无WMHs组相比伴有WMHs组的偏头痛患者既往合并脑梗死或短暂性脑缺血发作的比例更高(51 (52.6%) VS. 10 (11.0%), p = 0.000),其组间差异同样具有统计学意义(p < 0.05)。结果还发现WMHs组的左心房前后径、左心房长径、左心室舒张末期内径以及收缩末期内径相比无WMHs组更大(左心房前后径3.59 ± 0.43 VS. 3.27 ± 0.34,p = 0.000;左心房长径4.79 ± 0.57 VS. 4.50 ± 0.47,p = 0.000;左心室舒张末期内径4.53 ± 0.30VS.4.43 ± 0.28,p = 0.012;左心室收缩末期2.89 ± 0.30 VS. 2.80 ± 0.28,p = 0.041),而有WMHs组的心脏射血分数小于无WMHs组(63.98 ± 3.07 VS. 65.02 ± 3.52;p = 0.031),两组之间存在统计学差异(p < 0.05) (表3)。

Table 3. Vascular risk factors, chamber diameters and cardiac function makers between WMHs and non-WMHs group

表3. 有无WMHs组间的血管危险因素、心脏腔室径线、心脏功能标志物比较

aFischer精确检验。

3.4. 偏头痛患者WMHs的独立危险因素分析

对研究中所观察的具有统计学差异的指标进行单因素和多因素Logistic回归模型分析,研究结果表明LAAPD和RLS、年龄是偏头痛患者发生WMHs的独立危险因素(p < 0.05) (表4)。

4. 讨论

到目前为止,有些研究已经探讨了RLS与偏头痛之间的相关性 [22] [23] ,普遍被接受的一种假说是血清素等非被灭活的血管活性物质通过右向左分流绕过肺循环直接进入体循环从而导致偏头痛 [24] [25] 。这一假说得到了偏头痛患者接受PFO封堵术后头痛症状改善的证据支持 [26] [27] 。此外,也就研究认为通过RLS所产生的矛盾栓塞可能是偏头痛患者WMHs的发生机制 [28] [29] 。我们的研究显示在有RLS的130例偏头痛患者中WMHs发生率为57.5%,而在无RLS组中有WMHs的偏头痛患者占38.6%,WMHs在有RLS组中更常见,组间差异具有统计学意义。而且,经过Logistic多因素回归分析显示RLS是偏头痛患者WMHs的独立危险因素。本研究结果也支持了RLS参与了偏头痛患者的WMHs发病机制的观点。然而,有学者认为RLS与偏头痛患者的WMHs之间无明显相关性 [17] [30] ,所以,偏头痛患者的WMHs发生机制仍存争议。

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for WMHs in migraine patients

表4. 偏头痛患者WMHs的单因素和多因素回归分析

Regatelli等人 [13] 发现左房内径与RLS的严重程度存在相关性,长期的RLS会导致左心房增大及微血栓形成。他们证明左心房直径 > 43 mm是RLS的预测指标。然而,目前关于左心房内径与偏头痛患者WMHs发生机制的相关性研究较少。为了探讨左心房增大对偏头痛患者的WMHs的影响,本研究将纳入的188名偏头痛患者分为有WMHs组和无WMHs组,通过经胸超声心动图较易测量的并能够直观反映左心增大的左心房前后径(LAAPD)作为观察指标以及其它反映左心结构功能的径线标志进行组间比较,结果显示伴有WMHs组的LAAPD、左房长径、左室舒张末期内径及左室收缩末期内径均明显大于无WMHs组,其组间差异具有统计学意义,通过Logistic多因素回归分析发现LAAPD是伴有RLS偏头痛患者发生WMHs独立危险因素。Leifer等人 [16] 报道了LAE所致的心房性心脏病与不明原因栓塞性卒中(ESUS)的相关性。此外,Hamatani等 [31] 认为LAE是非瓣膜性心房颤动患者栓塞病变的独立预测因素。LAE可能通过以下几个方面对偏头痛患者WMHs的机制产生影响:首先,LAE是左心功能受损的原因之一,导致心输出量减少和脑灌注不足,进而可能导致脑白质亚临床缺血性损伤。Zhang,D等人 [32] 报道了脑灌注不足减少与WMHs之间密切相关。也有研究 [33] [34] 发现LAE与左心室舒张功能障碍和左心室压力升高有关,这在心脑血管事件中也起到一定的作用。其次,其机制可能与LAE引起左心房内血流血流排空减缓,血液粘稠度增高以及微血栓形成 [31] 有关。再次,LAE可能是导致左心房纤维化或心房颤动的重要原因之一,同样可以引起动脉微血栓形成以及脑白质病变 [35] [36] 。

为了探究RLS对偏头痛患者左房内径的影响,我们将偏头痛患者分为有RLS组和无RLS组,并根据c-TCD将有RLS组进一步分为大小分流量亚组进行研究,其结果未发现LAAPD等其它反映左心增大的径线以及左心功能标志在有无RLS组之间以及不同分流量亚组之间存在统计学差异。研究未显示偏头痛患者的RLS与LAAPD存在相关性。其原因可能与入组的偏头痛患者的年龄较轻(平均年龄43.3岁)不足以出现心脏结构失代偿改变有关,另外,有限的样本量可能也是影响研究结果的原因。目前有关RLS与LAE关系的研究甚少,两者之间是否存在相关性尚无定论。本研究还显示所纳入的伴有RLS的多数偏头痛患者在失代偿性左心增大前即出现了WMHs,随着年龄的增长,RLS在左心腔内径增大和WMHs机制中的作用可能逐渐明显。

研究中通过伴有和不伴WMHs组间比较,发现有WMHs组的左心室射血分数较无WMHs组下降,这可能与WMHs组的左心扩大进而心肌收缩力减弱有关。年龄在伴有与不伴有WMHs组间存在明显统计学差异,而且,经过多因素Logistic回归分析显示年龄是偏头痛患者WMHs独立危险因素。这一研究结果与其他学者的结论类似,Garnier-Crussard,A等人 [37] 也证实了年龄对成年人的WMHs的显著影响。Zhuang,FJ等人 [38] 认为年龄是WMHs患病率及严重程度的独立危险因素。此外,脑血管病危险因素如高血压、高脂血症在伴有WMHs组中更为普遍,在所纳入的伴有WMHs偏头痛患者中既往急性缺血性脑血管病事件也更为常见,这反映了高血压、脑血管病可能直接或间接的促进了WMHs的进展。Hannawi等人 [39] 研究发现在已知的心脑血管危险因素中,高血压与WMHs的发生密切相关。

本研究观察的LAAPD是常规经胸超声心动图检查中常见的测量径线之一,虽然不能全面的反映左心房大小,但其具有易测量获取、直观性强的特点是本次研究选取观察与WMHs有无相关性的重要原因。总之,在我们探索偏头痛患者WMHs的早期发病机制中,它可能作为脑功能障碍的独立危险因素进行干预。

我们的研究也存在一些局限性:首先,本研究属于单中心回顾性研究,其结论仅适用于本次研究。其次,研究对象仅限于偏头痛患者,且纳入样本数量有限。再次,所选LAAPD不是诊断左心房增大的金标准。

本次研究认为LAAPD是伴有RLS偏头痛患者发生WMHs的独立危险因素,LAE可能在具有RLS的偏头痛患者WMHs发病机制中起重要作用。对LAE相关机制的早期干预可能有助于延缓偏头痛患者WMHs的进展。

5. 结论

1) LAAPD是伴有RLS偏头痛患者发生WMHs的独立危险因素。

2) RLS是偏头痛患者WMHs的独立危险因素,而在偏头痛患者中LAAPD与RLS及其分级无关。

致谢

非常感谢我的导师张洪芹教授在课题筛选、实验设计以及论文撰写过程中的严格要求和耐心详尽的指导,以及感谢课题组同学们的支持与帮助。

文章引用

张 健,江 毅,单体茹,赵洪芹. 伴右向左分流的偏头痛患者左房前后径与脑白质病变的相关研究

Association between Left Atrial Anterior-Posterior Diameter and White Matter Hyperintensities in Migraineurs with Right-to-Left-Shunt[J]. 临床医学进展, 2024, 14(02): 3325-3338. https://doi.org/10.12677/ACM.2024.142470

参考文献

- 1. Steiner, T.J., Stovner, L.J., Vos, T., Jensen, R. and Katsarava, Z. (2018) Migraine Is First Cause of Disability in under 50s: Will Health Politicians Now Take Notice? The Journal of Headache and Pain, 19, Article No. 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0846-2

- 2. Santangelo, G., Russo, A., Tessitore, A., et al. (2018) Prospective Memory Is Dysfunctional in Migraine without Aura. Cephalalgia, 38, 1825-1832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102418758280

- 3. Peres, M.F.P., Mercante, J.P.P., Tobo, P.R., et al. (2017) Anxiety and Depression Symptoms and Migraine: A Symptom-Based Approach Research. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 18, Article No. 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0742-1

- 4. Zhang, Y., Parikh, A. and Qian, S. (2017) Migraine and Stroke. Stroke and Vascular Neurology, 2, 160-167. https://doi.org/10.1136/svn-2017-000077

- 5. Negm, M., Mohamed Housseini, A., Abdelfatah, M. and Asran, A. (2018) Relation between Migraine Pattern and White Matter Hyperintensities in Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 54, Article No. 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-018-0027-x

- 6. Martinez-Majander, N., et al. (2021) Association between Mi-graine and Cryptogenic Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults. Annals of Neurology, 89, 242-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25937

- 7. Borgdorff, P. and Tangelder, G.J. (2012) Migraine: Possible Role of Shear-Induced Platelet Aggregation with Serotonin Release. Headache, 52, 1298-1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02162.x

- 8. Song, S.Y., Kwak, S.G. and Kim, E. (2017) Effect of a Mother’s Recorded Voice on Emergence from General Anesthesia in Pediatric Patients: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials, 18, Article No. 430. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2164-4

- 9. Post, M.C. and Budts, W. (2006) The Relationship between Mi-graine and Right-to-Left Shunt: Fact or Fiction? Chest, 130, 896-901. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.130.3.896

- 10. Ling, Y., Wang, M., Pan, X., et al. (2020) Clinical Features of Right-to-Left Shunt in the Different Subgroups of Migraine. Brain and Behavior, 10, e01553. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1553

- 11. Harriott, A.M., Strother, L.C., Vila-Pueyo, M. and Holland, P.R. (2019) Animal Models of Migraine and Experimental Techniques Used to Examine Trigeminal Sensory Processing. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 20, Article No. 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1043-7

- 12. Rau, J.C. and Dodick, D.W. (2019) Other Preventive An-ti-Migraine Treatments: ACE Inhibitors, ARBs, Calcium Channel Blockers, Serotonin Antagonists, and NMDA Recep-tor Antagonists. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 21, Article No. 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-019-0559-0

- 13. Rigatelli, G., Zuin, M., Adami, A., et al. (2019) Left Atrial En-largement as a Maker of Significant High-Risk Patent Foramen Ovale. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Im-aging, 35, 2049-2056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01666-x

- 14. Park, H., Lee, S., Kim, S., et al. (2011) Small Deep White Matter Lesions Are Associated with Right-to-Left Shunts in Migraineurs. Journal of Neurology, 258, 427-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5771-5

- 15. 李艳晓, 薛茜, 仲婷婷, 等. 偏头痛患者心脏右向左分流与脑白质病变相关性研究[J]. 神经药理学报, 2021, 11(6): 31-34.

- 16. Leifer, D. and Rundek, T. (2019) Atrial Cardiopa-thy: A New Cause for Stroke? Neurology, 92, 155-156. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000006749

- 17. Jiang, X.H., Wang, S.B., Tian, Q., et al. (2018) Right-to-Left Shunt and Subclinical Ischemic Brain Lesions in Chinese Migraineurs: A Multicentre MRI Study. BMC Neurology, 18, Article No. 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1022-7

- 18. Busby, N., Wilson, S., Wilmskoetter, J., et al. (2023) White Mat-ter Hyperintensity Load Mediates the Relationship between Age and Cognition. Neurobiology of Aging, 132, 56-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.08.007

- 19. Al-Hashel, J.Y., Alroughani, R., Gad, K., Al-Sarraf, L. and Ahmed, S.F. (2022) Risk Factors of White Matter Hyperintensities in Migraine Patients. BMC Neurology, 22, Article No. 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02680-8

- 20. Phuah, C.L., Chen, Y.S., et al. (2022) Association of Data-Driven White Matter Hyperintensity Spatial Signatures with Distinct Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Etiologies. Neurology, 99, e2535-e2547. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000201186

- 21. Yang, Y.J., Knol, M.J., Wang, R.Q., et al. (2023) Epige-netic and Integrative Cross-Omics Analyses of Cerebral White Matter Hyperintensities on MRI. Brain, 146, 492-506.

- 22. Wilmshurst, P. and Nightingale, S. (2001) Relationship between Migraine and Cardiac and Pulmonary Right-to-Left Shunts. Clinical Science, 100, 215-220. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs1000215

- 23. Wammes-van der Heijden, E.A., Tijssen, C.C. and Egberts, A.C.G. (2006) Right-to-Left Shunt and Migraine: The Strength of the Rela-tionship. Cephalalgia, 26, 208-213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01024.x

- 24. Bajaj, D., Bandyo-padhyay, D., Mondal, S. and Ghosh, R.K. (2018) An Interesting Correlation between Patent Foramen Ovale and Mi-graine. International Journal of Cardiology, 256, 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.070

- 25. Liu, K.M., Wang, B.Z., Hao, Y., et al. (2020) The Correlation between Migraine and Patent Foramen Ovale. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, Article 543485. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.543485

- 26. Shi, Y.J., Lv, J., Han, X.T. and Luo, G.G. (2017) Migraine and Percutaneous Patent Foramen Ovale Closure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Car-diovascular Disorders, 17, Article No. 203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0644-9

- 27. Mojadidi, M.K., et al. (2021) Pooled Analysis of PFO Occluder Device Trials in Patients with PFO and Migraine. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 77, 667-676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.068

- 28. Park, H.K., Lee, S.Y., Kim, S.E., Yun, C.H. and Kim, S.H. (2011) Small Deep White Matter Lesions Are Associated with Right-to-Left Shunts in Migraineurs. Journal of Neurology, 258, 427-433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5771-5

- 29. Sztajzel, R., Genoud, D., Roth, S., Mermillod, B. and Le Floch-Rohr, J. (2002) Patent Foramen Ovale, a Possible Cause of Symptomatic Migraine: A Study of 74 Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 13, 102-106. https://doi.org/10.1159/000047758

- 30. Brunelli, N., et al. (2022) Cerebral Hemodynamics, Right-to-Left Shunt and White Matter Hyperintensities in Patients with Migraine with Aura, Young Stroke Patients and Controls. Interna-tional Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, Article 8575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148575

- 31. Hamatani, Y., Ogawa, H., Takabayashi, K., et al. (2016) Left Atrial Enlargement Is an Independent Predictor of Stroke and Systemic Embolism in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrilla-tion. Scientific Reports, 6, Article No. 31042. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31042

- 32. Zhang, D., Zhang, J., Zhang, B., et al. (2021) Association of Blood Pres-sure, White Matter Lesions, and Regional Cerebral Blood Flow. Medical Science Monitor, 27, e929958. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.929958

- 33. Sardana, M., Lessard, D., Tsao, C.W., et al. (2018) Association of Left Atrial Function Index with Atrial Fibrillation and Cardiovascular Disease: The Framingham Offspring Study. Jour-nal of the American Heart Association, 7, e008435. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.008435

- 34. Kizer, J.R., Bella, J.N., et al. (2006) Left Atrial Diameter as an In-dependent Predictor of First Clinical Cardiovascular Events in Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults: The Strong Heart Study (SHS). American Heart Journal, 151, 412-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.031

- 35. De Leeuw, F.E., De Groot, J.C., Oudkerk, M., et al. (2000) Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Cerebral White Matter Lesions. Neurology, 54, 1795-1801. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.54.9.1795

- 36. Kim, T.W., Jung, S.W., Song, I.U., et al. (2015) Left Atrial Dilatation Is Associated with Severe Ischemic Stroke in Men with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 354, 97-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.008

- 37. Garnier-Crussard, A., Bougacha, S., Wirth, M., et al. (2020) White Matter Hyperintensities across the Adult Lifespan: Relation to Age, Aβ Load, and Cognition. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 12, Article No. 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00669-4

- 38. Zhuang, F.J., Chen, Y., He, W.B. and Cai, Z.Y. (2018) Preva-lence of White Matter Hyperintensities Increases with Age. Neural Regeneration Research, 13, 2141-2146. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.241465

- 39. Hannawi, Y., Yanek, L.R., Kral, B.G., et al. (2018) Hypertension Is Associated with White Matter Disruption in Apparently Healthy Middle-Aged Individuals. AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 39, 2243-2248. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5871

NOTES

*通讯作者。