Advances in Environmental Protection

Vol.4 No.02(2014), Article ID:13384,13 pages

DOI:10.12677/AEP.2014.42007

The Review of Typical Halogenated Flame Retardants, HFRs Pollution in Indoor Air and Dust

Biological and Environmental Engineering School, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou

Email: 88603875@qq.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Hans Publishers Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: Mar. 21st, 2014; revised: Apr. 10th, 2014; accepted: Apr. 17th, 2014

ABSTRACT

Halogenated Flame Retardants (HFRs) used to reduce the polymer flammability are a kind of widespread typical pollutants in the indoor environment medium. They have a severe negative impact on human health. Polybrominated Biphenyl Ethers (PBDEs), Polychorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Dechlorane Plus (DP) are three kinds of the important Halogenated Flame Retardants. The present paper reviews the source, sampling, quantification, the pollution characteristics, pollution levels and human exposure of these HFRs in indoor environment.

Keywords:Halogenated Flame Retardants (HFRs); Indoor Air; Indoor Dust; Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs); Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs); Dechlorane Plus (DP)

室内空气与灰尘中典型卤代阻燃剂的

污染研究进展

林 敏

浙江工业大学生物与环境工程学院,杭州

Email: 88603875@qq.com

收稿日期:2014年3月21日;修回日期:2014年4月10日;录用日期:2014年4月17日

摘 要

卤代阻燃剂(Halogenated Flame Retardants, HFRs)是一类用于降低聚合物易燃性的功能性助剂,广泛存在于室内环境中,对人体健康有严重的负面影响。多溴联苯醚、多氯联苯、得克隆是三种典型的卤代阻燃剂(HFRs),本文介绍了室内这三类HFRs的来源、采样方法与分析技术,并结合国内外的研究报告简要总结室内环境中这三类HFRs的污染特征及污染水平。利用暴露模型分析这三类污染物的人体暴露。

关键词

卤代阻燃剂(HFRs);室内空气;室内灰尘;多溴联苯醚(PBDEs);多氯联苯(PCBs);得克隆(DP)

1. 引言

人一生中有70%左右的时间是在室内度过的,而许多城市居民的这一比例甚至达到90%。室内环境的质量已经被认定与人体健康有着密切联系[1] [2] 。然而目前全球的室内环境的空气质量不容乐观,美国环境保护局的一项研究成果表明,室内空气的污染程度一般要比室外严重2~5倍,在特殊情况下可达到100倍。室内空气污染已被归结为危害公共健康的5类环境因素之一。

据统计,全球近一半的人处于室内空气污染中,室内环境污染已引起35.7%的呼吸道疾病、22%的慢性肺炎和15%的气管炎、支气管炎和肺癌[3] [4] 。这些数据表明现今的室内空气质量现状令人担忧,甚至愈来愈引起人们的恐慌。

卤代阻燃剂(Halogenated Flame Retardants, HFRs)具有潜在的生物危害性,如干扰人体内分泌系统与神经系统[5] [6] ,是一类在室内环境中广泛存在的典型污染物。它包括氯代和溴代阻燃剂等[4] ,被广泛用于油漆、纺织品、电路板,尤其是电器电子产品的塑料外壳中。目前已开展了室内环境中卤代阻燃剂的来源、分析方法、污染特征、人体暴露得研究。本文对多溴联苯醚(Polybrominated Biphenyl Ethers, PBDEs)、多氯联苯(Polychorinated Biphenyls, PCBs)及得克隆(Dechlorane Plus, DP)三种典型的室内阻燃剂在这几领域的研究进展进行了概述。

2. 室内卤代阻燃剂的污染来源

2.1. 室内多溴联苯醚的来源

多溴联苯醚(PBDEs)是溴代阻燃剂中最主要的一类,被广泛添加于塑料制品、聚氨酯泡沫材料、纺织品、电路板等材料中[7] [8] 。由于没有形成稳定的化学键,PBDEs很容易从货物和产品中溢出[9] ,国内外专家通过对比PBDEs在室内环境与室外环境的浓度水平,比较一致地推断环境中PBDEs主要来自于室内环境[10] -[13] 。添加有溴代阻燃剂的电器(如电脑、电视机)和聚氨酯材料是室内空气中PBDEs的重要释放源[14] 。陈来国等[15] 发现不同家庭和办公室中存在的PBDEs工业品类型因室内设备的类型、品牌、新旧程度等不同而存在显著差异。例如,较老的电器中可能相对较多的使用了五溴二苯醚,而较新的电器则以十溴二苯醚为主。Allen等[16] 人研究表明,室内灰尘中的PBDEs来源于房间内饰中的含阻燃剂的材料。除室内排放源以外,室外大气对室内环境中的PBDEs的浓度水平也有一定影响,这种影响在开窗通风较多的夏季更为明显[17] 。此外,新软垫家具、床垫以及空气净化过滤器等也有影响[17] [18] 。

2.2. 室内多氯联苯的来源

多氯联苯(PCBs)是作为阻燃剂、增塑剂、胶黏剂等被添加于建筑材料、变压器、电器以及家具中[19] -[25] 。Herrick等[20] 发现用于嵌缝与密封的建筑材料中的PCBs等都导致对人体的暴露;Kohler[21] [22] 也提出密封胶是室内PCBs的一类不可忽视的来源;张志等[23] 探讨了室内PCBs与变压器油的相关性,发现的PCBs的与变压器油的轮廓很相似,都是轻氯PCBs含量较高,重氯PCBs含量较低,可能存在一定的源汇关系。此外室内普遍使用的含有PCBs的家具和电器(如沙发、床垫、电脑和电视机等)以及油墨、涂料以及荧光灯的整流器等的使用均会产生PCBs[24] 。Rudel就认为灰尘中的PCBs很可能就是从建筑材料中挥发进入空气中而后沉积到灰尘的结果[25] 。

2.3. 室内得克隆的来源

得克隆(DP)有顺式DP(syn-DP)与反式DP(anti-DP)两种同分异构体。DP作为灭蚁灵的替代品被广泛应用于电子产品、家具、纺织品等许多工业产品中[26] 。目前国内外对室内环境中(尤其是室内空气中)的DP研究还很少,甚至是基本没有,Ren等[27] 认为添加有DP的产品是室内DP的主要来源。Zhu等[28] 对比了渥太华室内灰尘样品中DP浓度值变化与附近的大湖底泥中DP的浓度变化,发现没有显著关联。

3. 室内空气和灰尘的分析方法

3.1. 室内空气的采样技术

室内空气采样主要分为主动技术与被动技术两种[11] ,其中空气采样的传统方法是使用主动大流量采样器,大流量主动采样器采用采气泵,形成负气压使气体通过采样器的补集装置,可以在短时间内采集数百立方米的大气样品,分别利用玻璃纤维滤膜采集大气颗粒物(固相)中的POPs,同时使用聚氨酯泡沫(PUF)吸附气态的POPs,其优点是采集所需时间短、采集体积大,缺点是采样器价格昂贵、体积庞大,难以多地点同时平行采集,且对操作人员要求较高,也会产生噪音[29] 。空气被动采样(PAS)技术在近10年来得到快速发展,它基于气体分子扩散和渗透原理利用吸附剂捕集空气中气态有机污染物,可用于定量分析空气中的PCBs、PBDEs、DP等持久性有机污染物,逐渐发展成为POPs监测的重要常规方法,相对于传统的主动采样技术,它可以对多个采样点同步布置和长期连续监测、得到时间加权平均浓度。多数PAS装置结构简单、造价低廉、操作方便、无需电源和特别维护。因而特别适用于较大区域范围内大气中POPs的观测,也适合于各种与人体暴露有关的微环境空气的观测。这在很大程度上弥补了大流量采样器的不足。目前使用的被动采样介质有半渗透膜装置(SPMD)、聚氨酯泡沫材料(PUF)和离子交换树脂(XAD)等。Wilford[30] 利用PUF被动采样技术监测了加拿大渥太华地区室内空气中的PBDEs,Harrad[31] 用相同技术对英国伯明翰的室内空气中的PBDEs进行了研究,Ren等[32] 也采用了PUF被动采样技术监测了中国大气中的DP。

3.2. 室内灰尘的采样技术

灰尘采样方法主要有用高容量表面采样器(HVS3)、家用吸尘器采集和毛刷掸子收集等[33] [34] 。高容量表面采样器将目标物吸附到特质材料样品袋(如聚乙烯拉链密封塑料袋)或纤维素提取顶针中,多用于采集房间内的灰尘颗粒等,其采集效率较高,但方法较繁琐,价格也较昂贵[35] 。家用吸尘器是高容量表面采用器的简易替代装置,Colt[33] 专门研究了两种采样器对不同化合物的采集效果,发现差别不大。相比较而言,高容量表面采样器和真空吸尘器更适合于采集稀松的灰尘、狭小缝隙里或物体表面的灰尘;而毛刷法采集更加方便与快捷,尤其是灰尘量较大的环境与当灰尘长久附着于载体表面(由于灰尘有一定湿度等原因)而导致一般功率的吸尘器很难吸附的情景。例如,Rudel等[36] 用尤里卡全能螨吸尘器收集灰尘于纤维素提取顶针中来进行采样监测。

3.3. 室内环境样品的预处理方法

样品的预处理技术主要包括富集与净化分离两部分。富集方法主要有索氏提取、超声萃取、超临界流体萃取、微波萃取等;净化分离方法主要有柱色谱净化以及凝胶渗透色谱净化两种。索氏提取法,又名连续提取法,是最常用、最经典的液–固萃取方法,利用溶剂回流和虹吸原理,提取效率很高,缺点是提取时间长,需要溶剂量比较大,并且很容易提取出其它有机物。Fromme[37] 、Harrad等[31] 都曾用索氏提取法提取大气、灰尘样品中的PBDEs。超临界流体萃取(SFE)是指用超临界流体为溶剂,从固体或液体中萃取可溶组分的传质分离操作。不仅效率较高,而且杜绝了有机溶剂,但设备较昂贵,不同污染物萃取条件参数不同,比较麻烦。于恩平等[38] 曾用SFE技术提取PCBs,Calvosa等用SFE方法提取灰尘中的PBDEs,Langenfeld等[39] 研究了用SFE技术提取PCBs。微波萃取是利用极性分子可迅速吸收微波能量的特性加热具有极性的溶剂,如甲醇、乙醇、丙酮等,萃取效率较高,使用溶剂较少,萃取时间短,但萃取效率受样品的含水率影响很大[40] 。

3.4. 卤代阻燃剂的仪器分析技术

通常用于卤代阻燃剂分析的仪器很多,比如气相色谱–四极杆低分辨质谱(GC-LRMS),气相色谱–高分辨质谱仪(GC-HRMS)和气相色谱串联四极杆质谱(GC-MS/MS),此外,还有气相色谱–电子捕获检测器(GC/ECD)、气相色谱–电感耦合等离子体质谱(GC-ICP/MS)、液相色谱–串联质谱(LC-MS/MS)等[41] 许多适用于分析PBDEs的技术也适用于PCBs以及DP。例如,Guvenius等[42] 、Rudel等[36] 采用GC-MS检测了BDEs与PCBs,ZHU等[28] 在测定DP的过程中也采用了GC-MS。其中PCBs更多地采用EI源(电子轰击电离),而PBDEs和DP则更多地采用NCI源(NCI,负化学电离)。因为DP使用EI源时产生的碎片离子强度较小导致相对于NCI方法的响应要低,灵敏性要差,所以低浓度的环境样品中的DP检测更适合用GC-NCI-MS[43] 。此外,色谱柱的长度和膜厚对溴代PBDEs尤其是BDE-209,BDE-209由于热降解作用在30 m的色谱柱中损耗严重,峰强度很小,这也是很多关于PBDEs的报道中没有包括BDE-209的主要原因,因此对高溴代PBDEs尤其是BDE-209的分析应用较短且膜厚较薄的色谱柱,但是对PCBs的分析为了获得更好的分离度,通常选用较长的色谱柱[44] [45] 。Konisas等[46] 了GC-NCI-MS与GC-ECD两种方式,结果显示NCI-MS的背景噪音、信噪比、选择性以及准确性均优于ECD(>10倍)。此外X射线荧光法(XFR)也可以用于测定室内灰尘或物体表面的卤代阻燃剂的含量,其通过测定目标样品中待测卤素的特征X射线照射量率,从而确定卤代阻燃剂的含量。Allen[47] 用XFR来测量灰尘中的PBDEs,Imm[48] 也曾用XFR来测量家具、床上用品、车内装饰以及电子设备上的PBDEs。

4. 室内环境中卤代阻燃剂的污染水平及特征

4.1. 室内环境中的多溴联苯醚

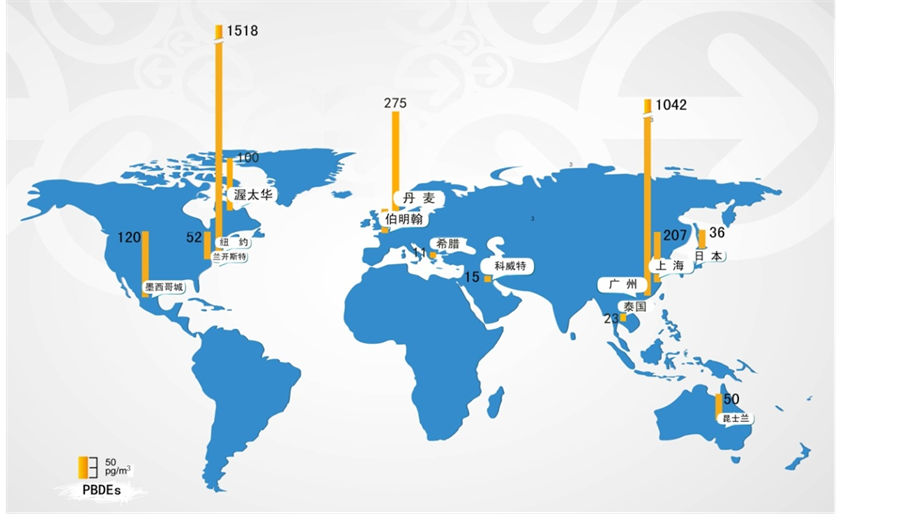

室内空气中的PBDEs:国内外不同地区的学者对室内环境中的PBDEs污染水平和特征的研究较为丰富,如图1所示,欧洲地区室内空气中的PBDEs相对于北美洲与亚洲要低很多。室内空气中PBDEs在季节变换、室内外差异、同系物浓度特征、地域污染水平等方面存在着差异。Wilford等[49] 人于2004年对加拿大渥太华地区室内外空气进行了观测,测得室内空气中总PBDEs的平均浓度是室外的50倍以上。Bohlin等人[50] 于2006年在美国兰开斯特、墨西哥城以及瑞典哥森堡采集室内空气样品并监测了BDE28、47、49、99、100、153以及154这7种同系物,测得三个地区的PBDEs浓度范围分别为4.7~620

Figure 1. PBDEs concentration of different area in indoor air (pg/m3) [49] -[53]

图1. 不同国家室内空气中的PBDEs浓度[49] -[53]

pg/m3,23~460 pg/m3,和5.5~52 pg/m3,其中BDE47、BDE99占的比重很高。Bergman等[51] 测得电子垃圾拆解区工厂空气的PBDEs的浓度达到了67,000 pg/m3,BDE47、BDE99及BDE209的含量较高。季节变化方面,夏季室内空气中的PBDEs普遍高于冬季,原因可能是夏季室内的高温导致PBDEs从电子电器设备和家具中的释放速度加快。韩文亮[17] 测得上海市城区办公室空气中PBDEs的平均浓度(冬季:139.8 ± 107.5 pg/m3,夏季:401.1 ± 551.5 pg/m3)高于家庭(冬季:97.5 ± 70.7 pg/m3,夏季:300.0 ± 246.6 pg/m3),这与办公室内电器产品的密集使用有关。Toms[52] 对比了澳大利亚昆士兰的家庭与办公室空气样品的PBDEs浓度水平,发现办公室样品中的浓度(15~487 pg/m3)要高于家庭居住点(0.5~179 pg/m3),原因很可能是办公地点电器的使用时间与使用频率要高于居住区的。

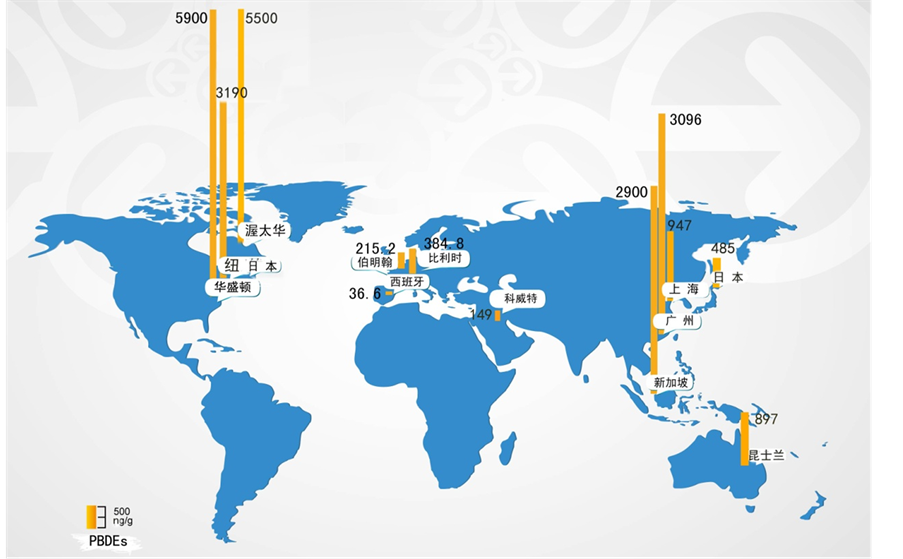

室内灰尘中PBDEs:室内灰尘中的PBDEs在空间功能类型、地区差异方面也体现出一定的污染特征。与室内空气有所不同,美国与亚洲地区的室内灰尘中的PBDEs要高于欧洲与大洋洲(图2),此外,灰尘中PBDEs的同系物组成与空气中的尤为不同。黄玉妹[54] 等分析了广州和海口52个家庭和12个办公室尘土中PBDEs。发现家庭尘土中的总含量为544.2~9654 ng/g,办公室灰尘的为1737~4408 ng/g,其中最主要的单体为BDE-209,而低溴联苯醚的含量较低。通过比对室内灰尘与室外对照灰尘可以证实,室内的PBDEs浓度大于室外,这表明室内有明显的PBDEs释放源。上述提到的Wilford等[30] 对渥太华地区的气样进行检测的同时,也分析了灰尘样品,在所有采集的灰尘样品中都检测到了BDE-209,平均浓度为1800 ng/g,平均占比42%,其次是BDE-47和BDE-99,说明PBDEs同系物中,BDE-209、BDE-47以及BDE-99的使用量要相对较多。渥太华的室内灰尘中PBDEs的浓度水平与美国华盛顿的比较接近,后者的浓度为780~30,100 ng/g,平均浓度为5900 ng/g [16] 。由此我们得出室内灰尘中BDE-209是最主要的单体,原因可能是高取代后导致BDE-209难挥发,经沉降而积累到灰尘中[55] 。

4.2. 室内环境中的多氯联苯

室内空气中的PCBs:不同地区室内空气和灰尘中都检测到了PCBs的存在(表1)。与PBDEs类似,

Figure 2. PBDEs concentration of different area in indoor dust (ng/g) [16] [34] [54] [55]

图2. 不同国家室内灰尘中的PBDEs浓度[16] [34] [54] [55]

表1. 世界不同地区室内空气中的PCBs浓度水平(ng/m3)

室内环境中的PCBs普遍高于室外环境。Zhang等[56] 在测定多伦多20个室内空气样品后发现,办公点的PCBs浓度要略高于居住点的,评价浓度分别为0.79和0.46 ng/m3,是同地区室外大气中浓度值的数倍。Harrad等[31] 对英国伯明翰的31户家庭、33个办公点及其25个汽车样品的研究中,PCBs的平均浓度甚至达到8920 pg/m3,办公地点的浓度高于家庭,并且都远远高于室外大气中的浓度,其中主要是三氯、四氯等低氯代PCBs。张志等[23] 等对哈工大的实验室以及办公室点的空气中的PCBs进行了检测,PCBs的浓度水平为450到1000 pg/m3,其中轻氯PCBs占大多数,浓度最高的是PCB33。Edward[57] 在研究美国哈得逊河社区176个室内点空气样品,测得PCBs平均浓度为14 ng/m3,浓度范围为0.6~233 ng/m3,其中PCB28的比例最高。泰国室内空气样品中PCBs也是以低氯代的为主,如PCB18、PCB28、PCB52、PCB101等,并且室内空气中PCBs的浓度远远大于室外的,这一现象对于城市区域的更为明显[58] 。Wilson等[59] 测得儿童护理中心室内空气中的PCBs浓度远高于室外的,也以低氯代为主。可以发现室内空气中的PCBs浓度明显高于同地区室外大气中的,原因很可能是由于室内存在PCBs的污染源,如电器、家具以及建筑材料等。而低氯代的PCBs由于相对较高的挥发速率更容易扩散积累在室内空气中,而高氯代PCBs挥发性较差,所以在空气中的含量与低氯代的相比要少。Lundsgaard[60] 在夏季观测到一个无人居住区室内空气中的PCBs浓度很高,推测与室外温度以及室内空气的低流通速率有关。Marie Frederiksen [60] 还研究了居住者行为与相应居住环境中PCBs浓度的关系,发现通风、吸尘、除尘以及清洗地板都有助于降低室内空气中的PCBs浓度。Menichini等[61] 对比了4栋建筑内不同楼层的室内空气中的PCBs浓度,发现高楼层的空气里的PCBs普遍要低于低楼层的,原因是低楼层的点受交通与道路因素影响较明显。此外,室内空气中PCBs浓度水平在时间趋势上,没有随时间迁移而显著降低[31] 。

室内灰尘中的PCBs:世界各地的室内灰尘中也被检测出了PCBs(表2),且在同系物组成、建筑功能与特征等方面存在规律。Hwang等[64] 对美国加利福尼亚地区的10个社区公寓点中的灰尘的研究显示,PCBs的浓度从10到227 ng/g,这一值虽比Wilson [59] 对儿童护理中心的灰尘样(120到3150 ng/g)与Vorhees等[65] 对美国新福贝尔德港口的取自室内地毯的灰尘(260~23,000 ng/g)的浓度要小很多,但还是有1个点浓度超过了美国EPA对居住区土壤浓度水平的风险线,3个点超过了加利福尼亚地区的风险线。

表2. 世界不同地区室内灰尘中的PCBs浓度水平(ng/g)

儿童护理中心的灰尘样浓度水平比室外土壤高2到3个数量级,而美国新福贝尔德港口的取自室内地毯的灰尘的PCBs是同地点户外院子中土壤浓度的10倍,其中PCB138、PCB153以及PCB180的检出率普遍较高。原因是室内家具、电器以及建筑材料中的PCBs溢出进去室内空气,进而沉积在固体颗粒以及室内灰尘中,而高氯代的PCBs(如PCB153、PCB180)由于较低的挥发性,更容易在颗粒物中积聚,导致灰尘中高氯代PCBs较空气中的含量要高。Laurence Roosens等[66] 测得比利时灰尘样品中PCBs平均浓度为19.7 ng/g,范围是6.5~41.9 ng/g,其中PCB138和PCB153在所有样品中都有检出,且所占比重最高。此外,Andersson、Colt和Kohler通过对比采样目标建筑的年龄与PCBs浓度都发现总体上老建筑中PCBs的浓度要高于相对而言较为新的建筑,推断房子的年龄可能是室内灰尘中PCBs浓度水平的一个重要指示物[21] [67] [68] 。

4.3. 室内环境中的得克隆

室内环境中关于DP的研究非常少,目前仅有少数几个地区的室内灰尘中DP的报道(图3)。尽管美国、加拿大和中国的室外大气中检测到了DP,但却没有室内空气中DP的研究[75] 。Zhu是国际上第一个检测室内环境中DP的,他于2002年11月到2003年3月以及2007年两次对加拿大渥太华家庭室内灰尘中的DP进行了研究,2002~2003年采集的灰尘样中DP的浓度范围为2.3~5683 ng/g,平均浓度为110 ng/g,2007年的灰尘样中的为14~61 ng/g,这些值都要高于离渥太华不远的大湖区底泥中测得的DP浓度值,表明室内存在DP污染源。而Shoeib等[76] 对加拿大温哥华116个室内灰尘样中的DP进行了检测,DP的浓度范围为0.8~384 ng/g,平均浓度为18.5 ng/g,并且发现顺式与反式DP有比较强的关联性。Robin等于2006年与2011年对加利福尼亚同样的16个家庭点中的DP进行了监测,测得2006年这16个家庭点的灰尘样品中DP的平均浓度为10 ng/g,其中反式DP的平均浓度为7.5 ng/g;而2011年的结果显示DP的平均浓度有所下降,为4.5 ng/g,其中反式DP为3 ng/g。Wang等[77] 对比了广州城市、农村区域与电子拆解区室内灰尘样品中的DP浓度,发现电子拆解区的DP浓度远远高于城区与郊区的,前者的浓度范围为0~21,000 ng/g,平均浓度为541 ng/g,而后两者分别为2.78~70.4 ng/g、13.8 ng/g与0~27.1 ng/g、3.95 ng/g,原因是电子产品中DP的溢出,而DP由于较低的挥发性,更容易在空气的颗粒物以及灰尘中。Zheng等[78] 再次监测了上述同一地区电子拆解区室内灰尘中的DP,测得工作车间灰尘样品中的DP浓度为342.8~4197 ng/g,居住区的为45.2~1798 ng/g。

5. 室内卤代阻燃剂的人体暴露量的估算

越来越多的研究表明室内空气吸入和室内灰尘摄取可能是人体暴露PBDEs的最主要的途径。对于PBDEs、PCBs及DP而言,呼吸吸入、灰尘摄入和灰尘皮肤接触是人体暴露的最主要的非饮食摄入途径[24] 。例如,Lorber[7] 对美国人受到PBDEs暴露的研究表明,室内灰尘暴露在总摄入量中的比重达到82%。国内外许多专家学者为了更为直观地建立污染物浓度水平与人体摄入之间的联系进行了研究探索,如Hearn[79] 、Kannan[80] 、Kohler[22] 、Gevao[81] 等。

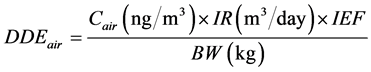

为了全面了解室以上三种环境污染物对人体的暴露情况,可以用Kannan等[80] 在评估室内环境中PBDEs的暴露水平中采用的Daily Exposure暴露模型中的室内空气吸入、灰尘摄入和灰尘皮肤接触模型,并参照美国EPA提供的各种暴露因子的参数,对三种非饮食摄入的日摄入量进行计算。三种模型的计算公式如下所示:

空气吸入途径:

(1)

(1)

式中DDEair表示通过呼吸吸入空气中污染物的日暴露量(ng/kg-bw·day);Cair表示室内空气中含卤阻燃剂的浓度(ng/m3);IR表示空气的吸入速率(m3/day),即每天的空气吸入量;IEF表示人体每天的室内暴露比率(day/day),即人类活动在室内环境中的时间占一天总时间的比例;BW表示人体平均体重(kg)。不同年龄段人群的体重、空气的吸收速率以及室内暴露比率不同,具体参数参照美国EPA提供的数据(表3)。

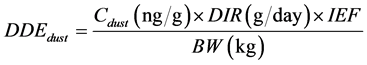

灰尘摄入途径:

(2)

(2)

其中DDEdust为通过灰尘摄入途径进入人体的日摄取量(ng/kg·bw·day);Cdust表示室内灰尘中含卤阻燃剂的浓度(ng/g);DIR表示人体对灰尘的日摄取量(m3/day),即每天摄入的灰尘量;IEF和BW同公式(1)相同分别表示人体每天的室内暴露比率(day/day)和人体平均体重(kg)。不同年龄段人群的灰尘日摄取量以及室内暴露比率和体重均不相同,具体参数如表3所示。

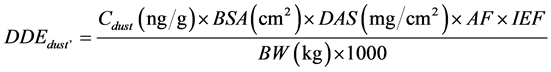

灰尘的皮肤灰尘接触暴露途径:

(3)

(3)

其中DDEdust’表示通过皮肤接触吸收途径的总日摄入量(ng/kg-bw·day);Cdust表示室内灰尘中的浓度(ng/g);BSA表示皮肤与灰尘的接触面积(cm2/day);DAS表示灰尘在皮肤表面的粘着量(mg/cm2),即每单位面积皮肤能够粘着的灰尘的质量;AF表示皮肤对污染物的吸收率;IEF和BW分别代表人体的室内暴露比率(day/day)和人体平均体重(kg)。不同年龄段人体的灰尘皮肤接触面积等影响因子不同,具体参数见表3。

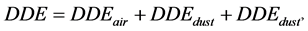

室内环境中非饮食摄入的暴露总量为灰尘摄入量、呼吸吸入量和皮肤的接触量之和,即:

目前文献已有PBDEs和PCBs这两类物质的人体暴露数值的可供参考。例如从刘洋[24] 的数据可知,儿童和成人对PCBs的日均暴露量达到1980和4772 pg/d,对PBDEs的日均暴露量达到930和2241 pg/d;对PBDEs的日均暴露量达到930和2241 pg/d。黄玉妹[54] 测得广州市区人群人体的PBDEs的呼吸暴露水平为11.9 ng/person/day,两种物质的日均暴露量都达到了ng/d的数量级,该地区成年人和婴幼儿通过摄人尘土摄人的PBDEs分别为1.5和14.5 ng/d。此外,婴幼儿的尘土摄人量远大于成年人,其对PBDEs的暴露水平高于成年人,尘土摄人是儿童暴露于PBDEs的主要途径。Harrad[83] 测得英国成人与儿童对

表3. 不同年龄段人群的暴露评估[82]

灰尘中PCBs的日暴露量分别为2.3、5.6 ng/d,美国的为4.4、11 ng/d,而对室内空气中PCBs的日暴露量为150 ng/d、28 ng/d。加拿大的成人与婴儿日均灰尘暴露量达到了5.8与18 ng/d。Zhu等[28] 测得加拿大成人与婴幼儿(6到24个月)对DP的日均暴露量分别为0.06跟0.75 ng/d。

6. 结论和展望

现有研究表明,室内卤代阻燃剂的大量存在与使用添加有卤代阻燃剂的电器、建筑材料、家具、纺织品等有关。室内卤代阻燃剂污染呈现出高浓度水平,高人均暴露量与摄入量的特征,对人体健康尤其是婴儿的健康存在潜在危害,需要继续深入这类污染物的监测分析技术、产生源调查、环境本底数据采集、迁移、污染发展趋势和毒理等方面的研究,建立全面、系统的人体健康危害评价方法和人体摄入、体内分布与代谢模型。

基金项目

浙江省自然科学基金(Y13B070031)。

参考文献 (References)

- [1] Chow, J.C., Watson, J.G.; Pritchett, L.C., Pierson, W.R., Frazier, C.A. and Purcell, R.G. (1993) The dri thermal optical reflectance carbon analysis system—Description, evaluation and applications in United-States air-quality studies. Atmospheric Environment. Part A. General Topics, 27, 1185-1201.

- [2] Chow, J.C., Watson, J.G., Crow, D., Lowenthal, D.H. and Merrifield, T. (2001) Comparison of IMPROVE and NIOSH carbon measurements. Aerosol Science and Technology, 34, 23-34.

- [3] 北镇 (2004) 中国室内环境污染危害严重. 世界环境, 5, 30-45.

- [4] Kierkegaard, A., Bignert, A., Sellstrom, U., Olsson, M., Asplund, L., Jansson, B. and de Wit, C.A. (2004) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and their methoxylated derivatives in pike from Swedish waters with emphasis on temporal trends, 1967-2000. Environmental Pollution, 130, 187-198.

- [5] Kuriyama, S.N., Wanner, A., Fidalgo-Neto, A.A., Talsness, C.E., Koerner, W. and Chahoud, I. (2007) Developmental exposure to low-dose PBDE-99: Tissue distribution and thyroid hormone levels. Toxicology, 242, 80-90.

- [6] Herbstman, J.B., Sjodin, A., Kurzon, M., Lederman, S.A., Jones, R.S., Rauh, V., Needham, L.L., Tang, D., Niedzwiecki, M., Wang, R.Y. and Perera, F. (2010) Prenatal exposure to PBDEs and neurodevelopment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118, 712-719.

- [7] Pijnenburg, A., Everts, J., De Boer, J. and Boon, J. (1995) Polybrominated biphenyl and diphenylether flame retardants: Analysis, toxicity, and environmental occurrence. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, Springer, Berlin, 1-26.

- [8] Mandalakis, M., Stephanou, E.G., Horii, Y. and Kannan, K. (2008) Emerging contaminants in car interiors: Evaluating the impact of airborne PBDEs and PBDD/Fs. Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 6431-6436.

- [9] Sjodin, A., Patterson, D.G. and Bergman, A. (2003) A review on human exposure to brominated flame retardants— Particularly polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environment International, 29, 829-839.

- [10] Huang, Y., Chen, L., Peng, X., Xu, Z. and Ye, Z. (2010) PBDEs in indoor dust in South-Central China: Characteristics and implications. Chemosphere, 78, 169-174.

- [11] Butt, C.M., Diamond, M.L., Truong, J., Ikonomou, M.G. and Ter Schure, A.F.H. (2004) Spatial distribution of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in southern Ontario as measured in indoor and outdoor window organic films. Environmental Science & Technology, 38, 724-731.

- [12] Harrad, S., Wijesekera, R., Hunter, S., Halliwell, C. and Baker, R. (2004) Preliminary assessment of UK human dietary and inhalation exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environmental Science & Technology, 38, 2345-2350.

- [13] Bjorklund, J.A., Thuresson, K., Cousins, A.P., Sellstrom, U., Emenius, G. and de Wit, C.A. (2012) Indoor air is a significant source of tri-decabrominated diphenyl ethers to outdoor air via ventilation systems. Environmental Science & Technology, 46, 5876-5884.

- [14] Jones-Otazo, H.A., Clarke, J.P., Diamond, M.L., Archbold, J.A., Ferguson, G., Harner, T., Richardson, G.M., Ryan, J.J. and Wilford, B. (2005) Is house dust the missing exposure pathway for PBDEs? An analysis of the urban fate and human exposure to PBDEs. Environmental Science & Technology, 39, 5121-5130.

- [15] 陈来国 (2009) 广州市大气环境中多溴联苯醚PBDEs和多氯联苯PCBs的初步研究. 博士论文, 中国科学院研究生院(广州地球化学研究所), 广州.

- [16] Allen, J.G., McClean, M.D., Stapleton, H.M., Nelson, J.W. and Webster, T.F. (2007) Personal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in residential indoor air. Environmental Science & Technology, 41, 4574-4579.

- [17] Rose, M., Bennett, D.H., Bergman, Å., Fängström, B., Pessah, I.N. and Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2010) PBDEs in 2 - 5 year-old children from California and associations with diet and indoor environment. Environmental Science & Technology, 44, 2648-2653.

- [18] Hale, R.C., La Guardia, M.J., Harvey, E., Gaylor, M.O. and Mainor, T.M. (2006) Brominated flame retardant concentrations and trends in abiotic media. Chemosphere, 64, 181-186.

- [19] Takasuga, T., Senthilkumar, K., Matsumura, T., Shiozaki, K. and Sakai, S.-I. (2006) Isotope dilution analysis of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in transformer oil and global commercial PCB formulations by high resolution gas chromatography—High resolution mass spectrometry. Chemosphere, 62, 469-484.

- [20] Herrick, R.F., McClean, M.D., Meeker, J.D., Baxter, L.K. and Weymouth, G.A. (2004) An unrecognized source of PCB contamination in schools and other buildings. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112, 1051-1053.

- [21] Kohler, M., Tremp, J., Zennegg, M., Seiler, C., Minder-Kohler, S., Beck, M., Lienemann, P., Wegmann, L. and Schmidt, P. (2005) Joint sealants: An overlooked diffuse source of polychlorinated biphenyls in buildings. Environmental Science & Technology, 39, 1967-1973.

- [22] Kohler, M., Zennegg, M. and Waeber, R. (2002) Coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) in indoor air. Environmental Science & Technology, 36, 4735-4740.

- [23] 张志, 李一凡, 任南琪 (2007) 室内空气中PCBs污染状况研究. 持久性有机污染物论坛2007暨第二届持久性有机污染物全国学术研讨会论文集.

- [24] 刘洋, 翼秀玲, 马静 (2011) 上海市典型家庭室内空气中PCBs与PBDEs初步研究. 环境科学研究, 5, 482-488.

- [25] Rudel, R.A. and Perovich, L.J. (2009) Endocrine disrupting chemicals in indoor and outdoor air. Atmospheric Environment, 43, 170-181.

- [26] 任南琪, 李一凡 (2011) 我国得克隆(dechlorane plus)的研究进展. 2011中国环境科学学会学术年会论文集(第四卷).

- [27] Ren, G.F., Yu, Z.Q., Ma, S.T., Li, H.R., Peng, P.G., Sheng, G.Y. and Fu, J.M. (2009) Determination of dechlorane plus in serum from electronics dismantling workers in South China. Environmental Science & Technology, 43, 9453-9457.

- [28] Zhu, J., Feng, Y.L. and Shoeib, M. (2007) Detection of dechlorane plus in residential indoor dust in the city of Ottawa, Canada. Environmental Science & Technology, 41, 7694-7698.

- [29] Levin, J.O., Andersson, K., Lindahl, R. and Nilsson, C.A. (1985) Determination of sub-part-per-million levels of formaldehyde in air using active or passive sampling on 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine-coated glass fiber filters and highperformance liquid chromatography. Analytical Chemistry, 57, 1032-1035.

- [30] Wilford, B.H., Harner, T., Zhu, J., Shoeib, M. and Jones, K.C. (2004) Passive sampling survey of polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in indoor and outdoor air in Ottawa, Canada: Implications for sources and exposure. Environmental Science & Technology, 38, 5312-5318.

- [31] Harrad, S., Hazrati, S. and Ibarra, C. (2006) Concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls in indoor air and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor air and dust in Birmingham, United Kingdom: Implications for human exposure. Environmental Science & Technology, 40, 4633-4638.

- [32] Ren, N.Q., Sverko, E., Li, Y.F., Zhang, Z., Harner, T., Wang, D.G., Wan, X.N. and McCarry, B.E. (2008) Levels and isomer profiles of dechlorane plus in Chinese air. Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 6476-6480.

- [33] Colt, J.S., Zahm, S.H., Camann, D.E. and Hartge, P. (1998) Comparison of pesticides and other compounds in carpet dust samples collected from used vacuum cleaner bags and from a high-volume surface sampler. Environmental Health Perspectives, 106, 721-724.

- [34] Simcox, N.J., Fenske, R.A., Wolz, S.A., Lee, I.C. and Kalman, D.A. (1995) Pesticides in household dust and soil: Exposure pathways for children of agricultural families. Environmental Health Perspectives, 103, 1126-1134.

- [35] Zhu, J., Feng, Y.-L. and Shoeib, M. (2007) Detection of dechlorane plus in residential indoor dust in the city of Ottawa, Canada. Environmental Science & Technology, 41, 7694-7698.

- [36] Rudel, R.A., Camann, D.E., Spengler, J.D., Korn, L.R. and Brody, J.G. (2003) Phthalates, alkylphenols, pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds in indoor air and dust. Environmental Science & Technology, 37, 4543-4553.

- [37] Fromme, H., Körner, W., Shahin, N., Wanner, A., Albrecht, M., Boehmer, S., Parlar, H., Mayer, R., Liebl, B. and Bolte, G. (2009) Human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), as evidenced by data from a duplicate diet study, indoor air, house dust, and biomonitoring in Germany. Environment International, 35, 1125-1135.

- [38] 于恩平 (1994) 用超临界流体萃取方法处理多氯联苯污染物. 北京化工学院学报, 21, 11-19.

- [39] Langenfeld, J.J., Hawthorne, S.B., Miller, D.J. and Pawliszyn, J. (1993) Effects of temperature and pressure on supercritical fluid extraction efficiencies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls. Analytical Chemistry, 65, 338-344.

- [40] Alothman, Z.A., Khan, M.R., Wabaidur, S.M. and Siddiqui, M.R. (2012) Persistent organic pollutants: Overview of their extraction and estimation. Sensor Letters, 10, 698-704.

- [41] 董亮, 张秀蓝, 史双昕, 许鹏军, 周丽, 杨文龙, 张利飞, 张烃, 黄业茹 (2013) 新型持久性有机污染物分析方法研究进展. 中国科学: 化学, 3, 010.

- [42] Guvenius, D.M., Aronsson, A., Ekman-Ordeberg, G., Bergman, A. and Norén, K. (2003) Human prenatal and postnatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, polychlorobiphenylols, and pentachlorophenol. Environmental Health Perspectives, 111, 1235.

- [43] Sverko, E., Tomy, G.T., Reiner, E.J., Li, Y.F., McCarry, B.E., Arnot, J.A., Law, R.J. and Hites, R.A. (2011) Dechlorane plus and related compounds in the environment: A review. Environmental Science & Technology, 45, 5088-5098.

- [44] Stapleton, H.M. (2006) Instrumental methods and challenges in quantifying polybrominated diphenyl ethers in environmental extracts: A review. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 386, 807-817.

- [45] Bjorklund, J., Tollback, P., Hiarne, C., Dyremark, E. and Ostman, C. (2004) Influence of the injection technique and the column system on gas chromatographic determination of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Journal of Chromatography A, 1041, 201-210.

- [46] Covaci, A., Voorspoels, S. and de Boer, J. (2003) Determination of brominated flame retardants, with emphasis on polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in environmental and human samples—A review. Environment International, 29, 735-756.

- [47] Allen, J.G., McClean, M.D., Stapleton, H.M. and Webstert, T.F. (2008) Linking PBDEs in house dust to consumer products using X-ray fluorescence. Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 4222-4228.

- [48] Imm, P., Knobeloch, L., Buelow, C. and Anderson, H.A. (2009) Household exposures to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in a Wisconsin cohort. Environmental Health Perspectives, 117, 1890-1895.

- [49] Wilford, B.H., Shoeib, M., Harner, T., Zhu, J. and Jones, K.C. (2005) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor dust in Ottawa, Canada: Implications for sources and exposure. Environmental Science & Technology, 39, 7027-7035.

- [50] Bohlin, P., Jones, K.C., Tovalin, H. and Strandberg, B. (2008) Observations on persistent organic pollutants in indoor and outdoor air using passive polyurethane foam samplers. Atmospheric Environment, 42, 7234-7241.

- [51] Sjodin, A., Carlsson, H., Thuresson, K., Sjolin, S., Bergman, A. and Ostman, C. (2001) Flame retardants in indoor air at an electronics recycling plant and at other work environments. Environmental Science & Technology, 35, 448-454.

- [52] Toms, L.M.L., Bartkow, M.E., Symons, R., Paepke, O. and Mueller, J.F. (2009) Assessment of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in samples collected from indoor environments in South East Queensland, Australia. Chemosphere, 76, 173-178.

- [53] Besis, A. and Samara, C. (2012) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in the indoor and outdoor environments—A review on occurrence and human exposure. Environmental Pollution, 169, 217-229.

- [54] 黄玉妹, 陈来国, 许振成, 彭晓春, 曾敏, 叶芝祥 (2009) 室内尘土中PBDEs的含量, 分布, 来源和人体暴露水平. 中国环境科学学会 2009年学术年会论文集(第四卷).

- [55] 张娴, 高亚杰, 颜昌宙 (2009) 多溴联苯醚在环境中迁移转化的研究进展. 生态环境学报, 2, 761-770.

- [56] Zhang, X., Diamond, M.L., Robson, M. and Harrad, S. (2011) Sources, emissions, and fate of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and polychlorinated biphenyls indoors in Toronto, Canada. Environmental Science & Technology, 45, 3268- 3274.

- [57] Fitzgerald, E.F., Shrestha, S., Palmer, P.M., Wilson, L.R., Belanger, E.E., Gomez, M.I., Cayo, M.R. and Hwang, S.A. (2011) Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in indoor air and in serum among older residents of upper Hudson River communities. Chemosphere, 85, 225-231.

- [58] Pentamwa, P. and Oanh, N.T.K. (2008) Levels of pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in selected homes in the Bangkok metropolitan region, Thailand. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1140, 91-112.

- [59] Wilson, N.K., Chuang, J.C. and Lyu, C. (2001) Levels of persistent organic pollutants in several child day care centers. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology, 11, 449-458.

- [60] Frederiksen, M., Meyer, H.W., Ebbehøj, N.E. and Gunnarsen, L. (2012) Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in indoor air originating from sealants in contaminated and uncontaminated apartments within the same housing estate. Chemosphere, 89, 473-479.

- [61] Menichini, E., Lacovella, N., Monfredini, F. and Turrio-Baldassarri, L. (2007) Relationships between indoor and outdoor air pollution by carcinogenic PAHs and PCBs. Atmospheric Environment, 41, 9518-9529.

- [62] Cupr, P., Skarek, M., Bartos, T., Ciganek, M. and Holoubek, I. (2005) Assessment of human health risk due to inhalation exposure in cattle and pig farms in south Moravia. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 74, 305-312.

- [63] Takigami, H., Suzuki, G., Hirai, Y. and Sakai, S. (2009) Brominated flame retardants and other polyhalogenated compounds in indoor air and dust from two houses in Japan. Chemosphere, 76, 270-277.

- [64] Hwang, H.M., Park, E.K., Young, T.M. and Hammock, B.D. (2008) Occurrence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in indoor dust. Science of the Total Environment, 404, 26-35.

- [65] Vorhees, D.J., Cullen, A.C. and Altshul, L.M. (1999) Polychlorinated biphenyls in house dust and yard soil near a Superfund site. Environmental Science & Technology, 33, 2151-2156.

- [66] Roosens, L., Abdallah, M.A.-E., Harrad, S., Neels, H. and Covaci, A. (2009) Current exposure to persistent polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p’-DDE) of Belgian students from food and dust. Environmental Science & Technology, 44, 2870-2875.

- [67] Andersson, M., Ottesen, R. and Volden, T. (2004) Building materials as a source of PCB pollution in Bergen, Norway. Science of the Total Environment, 325, 139-144.

- [68] Colt, J.S., Severson, R.K., Lubin, J., Rothman, N., Camann, D., Davis, S., Cerhan, J.R., Cozen, W. and Hartge, P. (2005) Organochlorines in carpet dust and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Epidemiology, 16, 516-525.

- [69] Ali, N., Eede, V.d., Neels, H. and Covaci, A. (2012) Country specific comparison for profile of chlorinated, brominated and phosphate organic contaminants in indoor dust. Case study for Eastern Romania, 2010. Environmental International, 49, 1-8.

- [70] Abb, M., Breuer, J.V., Zeitz, C. and Lorenz, W. (2010) Analysis of pesticides and PCBs in waste wood and house dust. Chemosphere, 81, 488-493.

- [71] 李琛, 余应新, 张东平, 冯加良, 吴明红, 盛国英, 傅家谟 (2010) 上海室内外灰尘中多氯联苯及其人体暴露评估. 中国环境科学, 4, 433-441.

- [72] Fabrellas, B., Martinez, A., Ramos, B., Ruiz, M.L., Navarro, I. and de la Torre, A. (2005) Results of an European survey based on pbdes analysis in household dust. Organohalogen Compound, 67, 452-454.

- [73] Harrad, S., Ibarra, C., Diamond, M., Melymuk, L., Robson, M., Douwes, J., Roosens, L., Dirtu, A.C. and Covaci, A. (2008) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in domestic indoor dust from Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom and United States. Environment International, 34, 232-238.

- [74] Ali, N., Ali, L., Mehdi, T., Dirtu, A.C., Al-Shammari, F., Neels, H. and Covaci, A. (2013) Levels and profiles of organochlorines and flame retardants in car and house dust from Kuwait and Pakistan: Implication for human exposure via dust ingestion. Environment International, 55, 62-70.

- [75] Xian, Q., Siddique, S., Li, T., Feng, Y.-l., Takser, L. and Zhu, J. (2011) Sources and environmental behavior of Dechlorane plus—A review. Environment International, 37, 1273-1284.

- [76] Shoeib, M., Harner, T., Webster, G.M., Sverko, E. and Cheng, Y. (2012) Legacy and current-use flame retardants in house dust from Vancouver, Canada. Environmental Pollution, 169, 175-182.

- [77] Wang, J., Tian, M., Chen, S.J., Zheng, J., Luo, X.J., An, T.C. and Mai, B.X. (2011) Dechlorane plus in house dust from E-waste recycling and urban areas in South China: Sources, degradation, and human exposure. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 30, 1965-1972.

- [78] Zheng, J., Wang, J., Luo, X.J., Tian, M., He, L.Y., Yuan, J.G., Mai, B.X. and Yang, Z.Y. (2010) Dechlorane plus in human hair from an e-waste recycling area in South China: Comparison with dust. Environmental Science & Technology, 44, 9298-9303.

- [79] Hearn, L.K., Hawker, D.W., Toms, L.M.L. and Mueller, J.F. (2013) Assessing exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) for workers in the vicinity of a large recycling facility. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 92, 222-228.

- [80] Johnson-Restrepo, B. and Kannan, K. (2009) An assessment of sources and pathways of human exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the United States. Chemosphere, 76, 542-548.

- [81] Gevao, B., Al-Bahloul, M., Al-Ghadban, A.N., Ali, L., Al-Omair, A., Helaleh, M., Al-Matrouk, K. and Zafar, J. (2006) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor air in Kuwait: Implications for human exposure. Atmospheric Environment, 40, 1419-1426.

- [82] Dellarco, V.L. and Wiltse, J.A. (1998) US Environmental Protection Agency’s revised guidelines for carcinogen risk assessment: Incorporating mode of action data. Mutation Research-Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 405, 273-277.

- [83] Harrad, S., Ibarra, C., Robson, M., Melymuk, L., Zhang, X., Diamond, M. and Douwes, J. (2009) Polychlorinated biphenyls in domestic dust from Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom and United States: Implications for human exposure. Chemosphere, 76, 232-238.